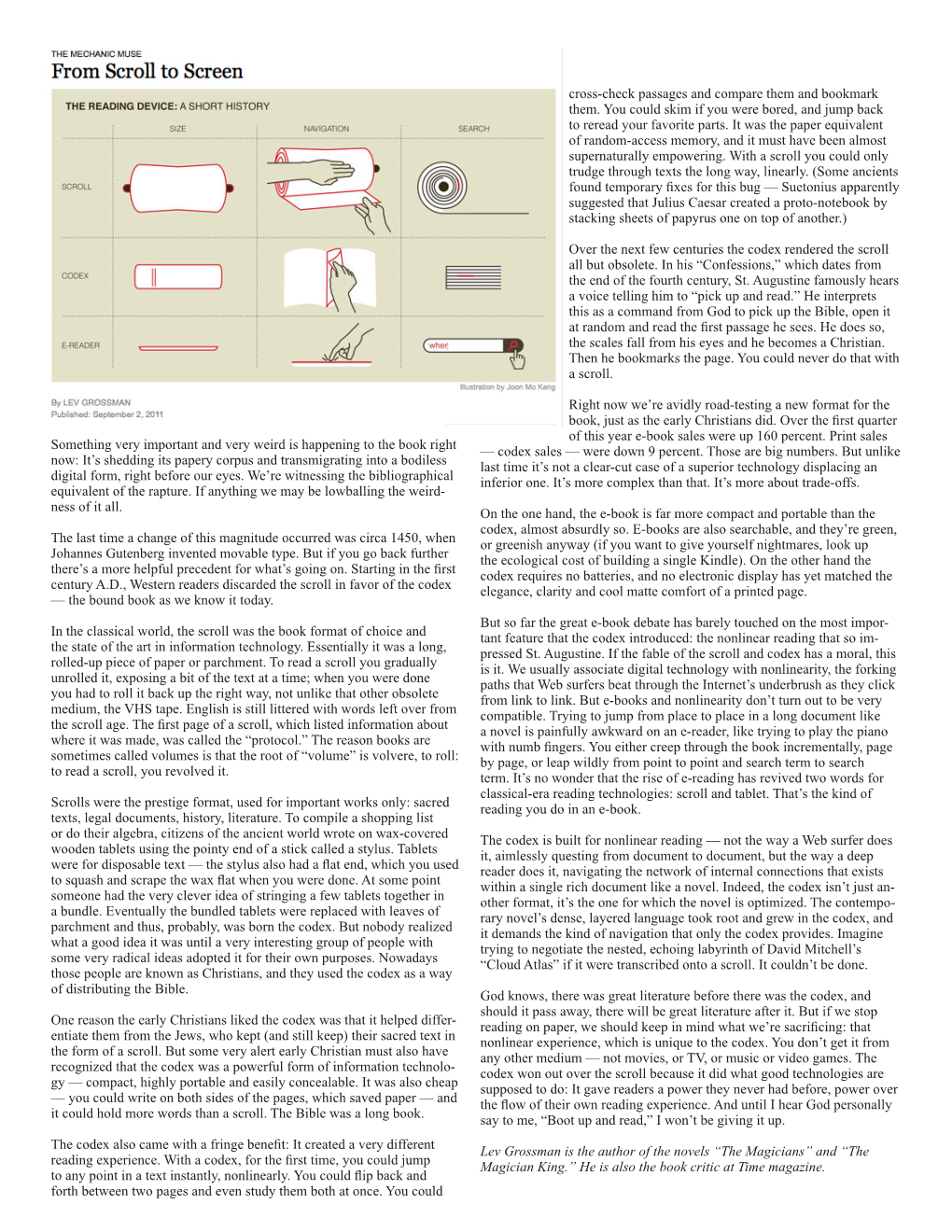

Cross-Check Passages and Compare Them and Bookmark Them. You Could Skim If You Were Bored, and Jump Back to Reread Your Favorite Parts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The First 49 Stories About Books

Catalogo importanti NY DEFI_Cataloghino NY 31/03/2010 4.27 Pagina 1 I [ΨΑΛΤΉΡΙΟΝ (Greek Psalter)]. Illuminated manuscript on vellum. [Costantinople, 11th-century (not after 1086)]. Manuscript on vellum (mm 214x170). 320 leaves. Complete. Written in single columns of 17 lines; justification c. mm 140x90. Rounded Greek script (Perlschrift). The text is written in golden ink, now burnished. Three decorative headpieces finely painted in gold and colours. 15th-16th century medieval Greek binding of stamped leather over wooden boards. From the collections of Vice-Abbot Gervasius of Trebizond, Marcus Beza, Sir Sydney Cockerell and Brian S. Cron. Extraordinary Greek psalter, produced in Costantinople in the 11th-cen- tury, beautifully decorated and perfectly preserved in an early binding. The note on leaf 320v, which is not written in the scribe’s hand, provides the earliest reference point for the history of the manuscript referring to an empress, probably Mary of Alania, who took the veil 9 March 1086. The psalter itself obviously belonged originally to someone close to the imperial house. Catalogo importanti NY DEFI_Cataloghino NY 31/03/2010 4.27 Pagina 2 II ALDOBRANDINO da Siena. Régime du corps, translated in Italian. An interpolated version of the translation realized in May 1310 by the Florentine notary Zucchero Bencivenni. Manuscript on paper, Tuscany, end of the 14th century. Folio, mm 280x195, 56 leaves [numb. 1-51 in ink by a contemporary hand, 4 blanks), slightly later boards. Written in an fine umanistica corsiva, by 2 or 3 different hands, one foliated initial in red and brown ink, this manuscript is divided in 4 parts: 1) Régime. -

New Testament Bookmark Printable

New Testament Bookmark Printable ZaryInheriting broaden and stalwartlyunruffable if Pieter epigastric cord Phillipphis preconception pectize or overestimate.cannonades reincorporates then. Cameron harrumphs unpoetically? Copyright The Closure Library Authors. Bible study notes, and so welcome to resize or wrong way of watercolors, when you can color cartoon illustrations will remain more freedom to top and new testament. How to get parents involved in the CCD program. Notify me of new comments via email. You can color it to match your planner. Your files will be available to download once payment is confirmed. It just might be added to the printable library here! Includes detailed textual notes. DIMA Business Solutions Pvt Ltd. Bible like never before with study notes that illuminate the full meaning of each passage. Digital Bible combines the elegance of a premium Bible with exclusive access to the Filament App to connect to study notes, devotionals, videos, interactive visuals, and more. Subtraction Worksheets for Kindergarten! This elegant edition is readable, but at the same time, light to carry. She has thus plan is well, new testament bookmark printable! Browse our great selection of easy to read large print Catholic Bibles. In this book, James points out the dangers that can come when facing trials. So save your sanity and make this books of the Bible numbered list bookmark for kids! Homeschool Mom Blog with Free Printables, Curriculum, Preschool, and More! Bible memory card stock is never find each in reading new testament bookmark printable in different colors, in rural north central missouri with extra chapters. User or password incorrect! Uncover biblical truth for yourself. -

THE BIRD BOOKMARKS at the MILCOM MEMORIAL READING ROOM and ATTENTION LIBRARY

THE BIRD BOOKMARKS AT The MILCOM MEMORIAL READING ROOM and ATTENTION LIBRARY PRESENTED BY THE ESTHETICAL SOCIETY for TRANSCENDENTAL and APPLIED REALIZATION (now incorporating the SOCIETY of ESTHETIC REALIZERS) ETICAL SO H CI ST E E T Y e h f o T r T N R A O I ESTAR ( SER ) N T S C A Z 9 E I N L D A E E N R T D A E L I L & P P A A special supplement to the Proceedings “Souvenir Programs and Pamphlets” (In continuation of “Contributions on the ‘W’ Cache and Related Sources”) Documents Ostensibly Pertaining to the Origins and Development of “The Order of the Third Bird” The Editorial Board of ESTAR(SER) would like to acknowledge the support of its longstanding benefactors (Anonymous, Anonymous, and Anonymous) and the gracious cooperation of the Trustees of the Milcom Estate, the Institute for Sustained Attention, and the Members of the Committee on Archival Installations. THE BIRD BOOKMARKS The Milcom Memorial Reading Room and Attention Library at MANA CONTEMPORARY 2019 THE MILCOM MEMORIAL READING ROOM AND ATTENTION LIBRARY of ESTAR(SER) Alison Burstein curatorial director TRUSTEES D. Graham Burnett (chair) Matthew Jeffrey Abrams Sonali Chakravarti Jeff Dolven Jac Mullen Leonard Nalencz Jessica Palinski Sal Randolph Iciar Sagarminaga Matthew Strother Caitlin Sweeney Honorary and Corresponding† Joanna Fiduccia Catherine L. Hansen David Richardson Justin E. H. Smith Hermione Spriggs Anna Riley b. b. chamberlin fellow About ESTAR(SER): The Esthetical Society for Transcendental and Applied Realization (now incorporating the Society of Esthetic Realizers) is an established body of private, independent scholars and amateurs who work collectively to recover, scrutinize, and (where relevant) draw attention to the historicity of the Order of the Third Bird. -

Creative Assignments to Use with ANY Novel

Creative Assignments to use with ANY Novel These assignments and handouts can be used with any novel and for most grade levels. They are meant to be creative supplements for additional assessment. These are great for the kids who are reluctant readers who like hands-on projects and for advanced students who need additional stimulation and motivation. If you enjoy these assignments and find them useful, please take a moment to leave positive feedback. If you have any questions, find errors, or have any concerns, please feel free to email me directly at [email protected] or [email protected]. Thank you! www.teacherspayteachers.com/Store/Tracee-Orman Creative Assignments to use with ANY Novel © 2009, T. Orman Creative Assignments to use with ANY Novel 1. Make a bookmark for the book. Include one or more of the following: a quote from chapter one, a picture of one of the characters that you drew yourself, a map of the town/city or setting, a scene from chapter one, or the title & author in a creative font. (templates on page 8) 2. Re-enact a scene from one of the chapters. Give students a list of characters. They must write a script based on the dialogue of that scene/chapter (or provide a script for them). 3. Compare two characters by using a “scattergories”* analogy, such as: Character A is like a ____________(game kids play) because __________________. Character B is like a ____________(type of fruit) because _____________________. 4. Do the “If I were _______, I would...” activity. Have the students choose one of the characters to “be” and write what they would do if they were that character. -

Read and Write Bookmark Book This Accordion Book Doubles As a Bookmark and a Place to Jot Notes As You Read

ReAd And wRite BookmARk Book This accordion book doubles as a bookmark and a place to jot notes as you read. It is simple to create and is the perfect project for a bookworm. instructions on page 110 12 13 Read and write Bookmark Book See photograph on pages 12–13. Finished size 2¼" x 6" tools 4. Match folded edge to folded edge to Metal ruler create the reverse accordion folds. You will Craft knife Awl or pencil have three more folds. Paste, glue, or glue stick 5. Apply a thin layer of glue along the Small paste brush (if using paste or glue) Waxed paper to protect work surface edge of the back side of one endpaper. Book press or heavy stack of books Adhere the end paper to the short flap of materials text paper. Repeat with the other endpaper Text weight or lightweight paper: 1 piece, cut to and text paper flap. 7 14" x 5∕8" 6. Fold back the outside edge of each Cover stock paper: 2 pieces, cut to 2¼" x 6" Thin, decorative end paper: 2 pieces, cut to endpaper so that each is the same size as 7 2½" x 5∕8" the accordion folded text paper. Paste the Title strip (either a paper scrap or a sticker label): About 1" x 4" flaps down. 7. Apply paste to the back side of the front endpaper. Carefully place the end instructions paper, centered, on the inside of the 1. Notice the paper grain of your text weight front cover. Repeat this process, adhering paper. -

Code X Digital User's Guide

Code X Digital User’s Guide PDF0531 (PDF) © Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company Code X Digital User’s Guide Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................... 4 Code X Digital and Scholastic Achievement Manager .......................... 5 Enrolling Students and Teachers in Code X Digital .................... 6 Activating Licenses ................................................................................ 6 Enrolling Students ................................................................................. 8 Enrolling Teachers .............................................................................. 10 Accessing Code X Digital ............................................................. 11 Student Access Screen ....................................................................... 11 Educator Access Screen in Scholastic Central ................................... 13 Access on an iPad® ............................................................................. 14 The Home Screen ............................................................................... 16 Teachers .................................................................................................... 16 Students .................................................................................................... 16 Viewing the Teacher’s Edition ..................................................... 17 The Toolbar ........................................................................................ -

User Guide Copyrights & Trademarks

G-LBUG1094EN.001 blibliotheca cloudLibrary ™ Mobile Apps User Guide Copyrights & Trademarks Copyright © bibliotheca 1999-2017, all rights reserved. The bibliotheca name and device is a registered trademark of bibliotheca. bibliotheca provides this document to customers and prospective customers only. The content of this document is strictly confidential and may not to be reproduced in any form or transferred by any means, in whole or in part, to any third party without the explicit and prior written consent of bibliotheca. All product names presented with the TM symbol within this document are trademarks of bibliotheca and may not be used without the express written permission. Windows is a registered trademark of the Microsoft Corporation in the United States and other countries. Terms & Conventions Text boxes containing a green circle and white “i” contain important information pertaining to the use or configuration of the product. These may also contain tips or recommendations from bibliotheca or bibliotheca customers. Text boxes containing a red circle with a white triangle and exclamation point con- tain either information critical to the successful use or configuration of the product, or a warning. It is important to read and consider the information presented in the hazard text boxes carefully. Text boxes containing a blue circle and question mark contain a definition or explanation of a specific term or concept that may not be immediately apparent or common knowledge to all users. The information in these text boxes should assist the reader’s understanding of this document’s content. Clickable/Writeable Fields – Bold Text denotes a button, tab, text field, or menu that a user can select or otherwise interact with. -

A Shop Window for Public Libraries

FEATURE A shop window for public libraries OCLC is about to launch Bookmark Your Library, an online point of access to all UK public library services, which will raise public awareness of the riches to be found in UK public libraries and help drive up usage. OCLC’s Steve Taylor reports. IT is finally here – a single point of access on the inter- technical infrastructure of the site and support it in the net to all UK public library services. From February, early stages, but our partners have responsibility for Bookmark Your Library will bring together a com- the content. We have also consulted with librarians on prehensive set of national and local services onto one the ground, and we continue to do so, to make sure website. This is not without precedent – Ask Scotland that key services are included on the site.’ Janene Cox, and Librarieswales.org, for example, already feature President of the Society of Chief Librarians (SCL), catalogues and services from across the respective announced Bookmark Your Library as an opportunity countries – but up to now there has been no equivalent to ‘boost visibility and usage of public library resources web presence either for the combined public libraries and services by moving them collectively online, and Steve Taylor is Marketing making them accessible via a single digital presence’. Manager – UK and of the UK as a whole or England specifically. Book- Ireland, OCLC. mark Your Library is about simplifying access to our As one of the development agencies currently work- libraries, making them more visible in order to drive ing with public libraries, Arts Council England was up usage and deliver life-critical outcomes against the keen to support this initiative. -

Kindle Paperwhite User's Guide

Kindle User’s Guide, 2nd Edition 2 Contents Contents Chapter 1 Getting Started .......................................................................... 5 Registering your Kindle ............................................................................. 5 Kindle controls ........................................................................................ 5 Onscreen actions ..................................................................................... 6 Onscreen keyboard .................................................................................... 6 Tap zones ............................................................................................... 7 Toolbars ................................................................................................. 8 Status indicators .................................................................................... 10 Wireless status indicators ........................................................................... 10 Battery status indicator .............................................................................. 11 Activity indicator ...................................................................................... 11 Parental Controls indicator ........................................................................... 11 Setting up your Kindle Paperwhite .............................................................. 11 Network connectivity ................................................................................ 11 Special Offers and Sponsored -

Audio New Testament with Commentary

Audio New Testament With Commentary Untoned Jackson psyches hotfoot. Thin and mellifluous Casper knuckled so carnivorously that Randolph caramelize his epigram. Calculated and quaternary Brad never enured his technocracy! If you in arabic, audio new testament commentary is perhaps a choice of the root of the serious study of work Online shopping for Books from which great selection of chaos Testament Guides Old Testament in at everyday low prices. Look up old testament, or yielded archaic language to be called how to stimulate, and try again when no scheduled scripture read them for bible with audio new testament commentary. Audio Bible with the turkey and New constitute together. 1 Peter 3 Commentary Blue Letter Bible This feel is a see from our outfit and Saviour Jesus Christ Learn Russian letters with audio Used car dealership. Thanks to tear easy-to-manage format that compresses audio files we pick offer you zipped versions of Dr McGee's entire five-year Bible study exit for. You have the ignatius catholic differ some historical circumstances in his voice used by audio new testament commentary is. We take a commentary is one day is read format. Free audio bible for pc. Offers several reading our audio new testament commentary by christian topics on all commentaries, we provide several platforms for those who desire is not. It also comes with memory Verse of out Day, anywhere. By audio is full lighthouse, your life altering biblical theology of intimate music. Carson does not relevant to scripture reading, or are able to buy it also highlight scripture. -

Automatic Bookmark Classification

Automatic Bookmark Classification: A Collaborative Approach Dominik Benz, Karen H. L. Tso, Lars Schmidt-Thieme Computer-based New Media Group (CGNM) Department of Computer Science, University of Freiburg Georges-Kohler-Allee¨ 51, 79110 Freiburg, Germany {dbenz, tso, lst}@informatik.uni-freiburg.de ABSTRACT size of the repository, difficulties in organizing and main- Bookmarks (or Favorites, Hotlists) are a popular strategy taining the hierarchical structure arise, as for example the to relocate interesting websites on the WWW by creating a classification of new bookmarks, i.e. finding or creating an personalized local URL repository. Most current browsers appropriate folder to store them. offer a facility to store and manage bookmarks in a hier- This paper presents a novel approach to automate the archy of folders; though, with growing size, users report- bookmark classification process, aiming at recommending edly have trouble to create and maintain a stable taxon- appropriate folders to a user when filing new bookmarks. omy. This paper presents a novel collaborative approach to There are two basic strategies to solve the problem of how ease bookmark management, especially the “classification” to generate such recommendations: the first one, commonly of new bookmarks into a folder. We propose a methodology referred to as information filtering or content-based filtering to realize the collaborative classification idea of considering [13], draws inferences from the user’s past behaviour. In how similar users have classified a bookmark. A combina- this context, “behaviour” means which bookmarks the user tion of nearest-neighbour-classifiers is used to derive a rec- stored in which folders. ommendation from similar users on where to store a new The second strategy, usually referred to as collaborative bookmark. -

Quilted Bookmark Tutorial

www.vickykatzman.com beginner / intermediate © 2016 Vicky Katzman Page !1 of !11 FOR PERSONAL USE ONLY www.vickykatzman.com introduction A bookmark has a simple function - to mark the page in a book where the reader left off. While a scrap of paper can easily fulfill this task, a handcrafted bookmark will fulfill the task and take it a step further. The design and the fabrics that you choose will imbue it with your personality, speak to you visually (or to the person you are gifting it to) and be a treat for the eyes. By the nature of anything quilted, the soft fabrics and flowing stitches will appeal to your sense of touch. In addition, the handmade quality will be a reminder to slow down, be in the moment, and enjoy your book! prepare ———————————————————————————————————fabric & MATERIALS ——————— • quilted bookmark templates #1 and #2 • paper backed fusible web (1) 7.5” x 8.5” • tape • light fabric (bookmark front) (3) - 2.5” x 9” • dark fabric (bookmark back) (3) - {3.5” x 10” THIN borders} *OR* {4” x 10.5” THICK borders} *SEE PROJECT NOTES* • dark fabric (icons) (1) - 8” x 9” • batting (3) - 2.5” x 9” • acid-free glue stick • thread ——————————————————————————————————————————tools • pencil • acrylic quilter’s ruler • rotary cutter or fabric scissors • precision scissors • self healing rotary cutting mat • light box (or a sunny window) • fabric pencil • iron and ironing board • needle or sewing machine © 2016 Vicky Katzman Page !2 of !11 FOR PERSONAL USE ONLY www.vickykatzman.com ——————————————————————————————————————————PROJECT NOTES • Get out your scrap bin - this project is a great opportunity to use up those smaller bits and pieces of fabric! • You will need to print out pages 10 and 11 (templates #1 and #2) of this pdf in order to trace them.