Chapter 5 NSW 190210 Reduced

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report HIA -- the Voice of the Industry

Housing Industry Association Limited includes Concise Financial Report HIA for the year ended 31 December 2016 2 016annual report HIA -- the voice of the industry HIA’S BOARD OF DIRECTORS Back row (L–R): Tim Olive, Chief Executive – Business Solutions; James Graham, Director; Stuart Wilson, Past President; Graham Wolfe, Deputy Managing Director; Glenn Simpson, General Counsel; Simon Norris, Director; Brian O’Donnell, Director; Alwyn Even, Director; David Linaker, Director. Front row (L–R): Terry Jenkins, Treasurer; Pino Monaco, Vice President; Ross Lang, President; Shane Goodwin, Managing Director; Ron Dwyer, Immediate Past President. Ian Hazan filled the casual vacancy left by the sad passing of Brian O’Donnell during the year. During the year, more than 230,000 Policy Imperatives that outlined the key Report to Members new homes commenced nationally. areas for government action and policy A record number, exceeding the reform. Housing affordability became previous high of 225,000 during the dominant political issue for the 2015, and eclipsing the decade election, enabling the Association to average by almost 65,000 homes. elevate land and housing supply, 2 016 Incredibly, these new homes will planning delays and taxes on new house almost 500,000 Australians homes as the priority challenges. and their families. But the political and public debate However, building activity wasn’t was not all one way, as HIA lobbied uniform across the country. Members stridently against proposals to in many regions watched on as NSW, change negative gearing and capital Victoria, and to a lesser extent, gains tax arrangements for residential South-Eastern Queensland, property investors. -

27 March 2018

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF NEW SOUTH WALES BANCO COURT BATHURST CJ AND THE JUDGES OF THE SUPREME COURT Tuesday 27 March 2018 FAREWELL CEREMONY FOR THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE CAROLYN SIMPSON UPON THE OCCASION OF HER RETIREMENT AS A JUDGE OF THE SUPREME COURT OF NEW SOUTH WALES 1 BATHURST CJ: We are here this morning to mark the occasion of the Honourable Justice Carolyn Simpson’s retirement as a Judge of the Court of Appeal. This ceremony gives us the opportunity to show our gratitude for the 24 years of service you have given to the administration of justice in this State, first in the Common Law division, and more recently in the Court of Appeal. 2 You became a judge in 1994. It is with no disrespect that I note you were appointed three months before your current tipstaff was born. You have served this Court tirelessly since then. There is only one complaint I can make. Your Honour is far too humble and reserved about your own achievements. It made the construction of this address rather difficult. Predictably, I firstly turned to your swearing in speech, marked Tuesday the 1st of February 1994. It is, of course, reflective of your humility. 3 You spent the entirety of it thanking those who had helped you along the way. You also noted that your oath of office was a commitment to the public, and the Court, and you pledged to do your utmost to justify the faith that had been placed in you. You can be rest assured that the vow you made at that time 1 has been more than fulfilled. -

Legislative Assembly- PROOF Page 1

Tuesday, 4 August 2020 Legislative Assembly- PROOF Page 1 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Tuesday, 4 August 2020 The Speaker (The Hon. Jonathan Richard O'Dea) took the chair at 12:00. The Speaker read the prayer and acknowledgement of country. [Notices of motions given.] Bills GAS LEGISLATION AMENDMENT (MEDICAL GAS SYSTEMS) BILL 2020 First Reading Bill introduced on motion by Mr Kevin Anderson, read a first time and printed. Second Reading Speech Mr KEVIN ANDERSON (Tamworth—Minister for Better Regulation and Innovation) (12:16:12): I move: That this bill be now read a second time. I am proud to introduce the Gas Legislation Amendment (Medical Gas Systems) Bill 2020. The bill delivers on the New South Wales Government's promise to introduce a robust and effective licensing regulatory system for persons who carry out medical gas work. As I said on 18 June on behalf of the Government in opposing the Hon. Mark Buttigieg's private member's bill, nobody wants to see a tragedy repeated like the one we saw at Bankstown-Lidcombe Hospital. As I undertook then, the Government has taken the steps necessary to provide a strong, robust licensing framework for those persons installing and working on medical gases in New South Wales. To the families of John Ghanem and Amelia Khan, on behalf of the Government I repeat my commitment that we are taking action to ensure no other families will have to endure as they have. The bill forms a key part of the Government's response to licensed work for medical gases that are supplied in medical facilities in New South Wales. -

Networked Knowledge Media Reports Networked Knowledge Evan Whitton Homepage This Page Set up by Dr Robert N Moles on 13 January

Networked Knowledge Media Reports Networked Knowledge Evan Whitton Homepage This page set up by Dr Robert N Moles On 13 January 2018 Andrew Urban in Pursue Democracy reported ‘Bare faced lawyers: confessions of the legal profession’ Innocent people – at least 71 known*, the total unknowable – have been held or are stuck in Australian jails on lengthy sentences for murders or rapes they did not commit. This comes as no surprise to those who, like multi award winning journalist and legal historian Evan Whitton, consider the adversarial system Australia has imported from Britain a disaster for justice, nothing more than a permit for lawyers to operate as a cartel, in which truth is not the ultimate objective. Winning is. Here, in a selection of extracts from Whitton’s infinitely researched and damning work, Our Corrupt Legal System (Book Pal, 2009), is the evidence – often in their own words: lawyers are trained liars. “The legal trade, in short, is nothing but a high-class racket.” Professor Fred Rodell, of Yale Law School, in Woe Unto You, Lawyers! (1939) * Dr Rachel Dioso-Vila, Griffith University Innocence Project, Flinders Law Journal 1 The Barton Hypothesis Associate Professor Benjamin Barton, of the University of Tennessee College of Law, put the question, Do Judges Systematically Favor the Interests of the Legal Profession? in the Alabama Law Review of December 2007. In what may be termed the Barton Hypothesis, he answered his question thus at page two of his 52-page (14,821 words) paper: “Here is my lawyer-judge hypothesis in a nutshell: many legal outcomes can be explained, and future cases predicted, by asking a very simple question: is there a plausible legal result in this case that will significantly affect the interests of the legal profession (positively or negatively)? If so, the case will be decided in the way that offers the best result for the legal profession.” The origin of lawyers’ immunity from suit is a brazen example of the Barton Hypothesis. -

Judicial Commission of New South Wales District Court

2968 JUDICIAL COMMISSION OF NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT COURT OF NEW SOUTH WALES ANNUAL CONFERENCE 2018, LEURA MY FIRST JUDGES - TEN LESSONS The Hon. Michael Kirby AC CMG JUDICIAL COMMISSION OF NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT COURT OF NEW SOUTH WALES ANNUAL CONFERENCE 2018, LEURA MY FIRST JUDGES - TEN LESSONS* The Hon. Michael Kirby AC CMG** RETURN TO ORIGINS I congratulate the judges of the District Court of New South Wales on another year of service. The court was established in 1858.1 It is 160 years since its creation. This is the second time I have addressed this annual conference. The first occasion was in 1988, soon after my appointment in 1984 as the fifth President of the New South Wales Court of Appeal.2 It must have been an unmemorable address on that occasion. It has taken 30 years for the invitation to be renewed. The * Text for the address to the dinner of the Judges of the District Court of New South Wales, Leura, New South Wales, 3 April 2018 ** Justice of the High Court of Australia (1996-2009); President of the New South Wales Court of Appeal (1984-96). 1 District Court Act 1858 (NSW) (22 Vic No. 18). 2 After Wallace P, Sugerman P, Jacobs P and Moffitt P. 1 Chief Judge at the time (appointed in 1971) was Judge James Henry Staunton QC. Not a single one of the judges then present is here to tell the tale. Most have died. So the secret is safe with me. The event took place in a Sydney CBD hotel. -

2021 Student Handbook 2021

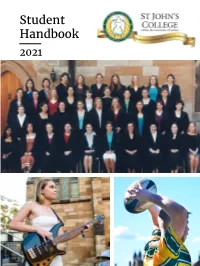

Student Handbook 2021 Student Handbook 2021 Ninth edition, 2021 Edited by Adrian Diethelm Designed and typeset by Bianca Dantl Thanks are due to College staff past and present who have contributed to this publication. © Copyright 2013-2021 The Rector and Fellows of St John’s College IMPORTANT CONTACTS EMERGENCY SERVICES Police | Ambulance | Fire 000 NEWTOWN POLICE Open 24 hours 131 144 or 02 9550 8199 UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY SECURITY Emergency (24 hours) 02 9351 3333 Security (non-emergency) 02 9351 3487 RESIDENT ASSISTANT ON DUTY Available after hours 0411 961 746 RECEPTION Mon-Fri 9am-5pm 02 9394 5000 STUDENT SERVICES Email [email protected] Cover top photo: The first cohort of women students 2001. 2 ST JOHN’S COLLEGE - STUDENT HANDBOOK | 2021 CONTENTS 1. OUR PURPOSE 5 7. HEALTH AND SAFETY 53 1.1 MISSION, VISION & CULTURE 5 7.1 STAYING HEALTHY 53 1.2 UNIVERSITY EDUCATION 6 7.2 ALCOHOL AND OTHER DRUGS 54 1.3 CULTURAL RENEWAL 7 7.3 REPORTING AND SUPPORT 56 1.4 THE UNIVERSITY AND THE CHURCH 8 7.4 LOCAL HEALTH RESOURCES 64 2. WHO’S HERE 10 8. STUDENT CODE OF CONDUCT 66 2.1 COLLEGE EXECUTIVE 10 9. THE GENERAL REGULATION 72 2.2 COLLEGE STAFF 12 10. POLICIES AND PROCEDURES 84 2.3 STUDENT PASTORAL TEAM 15 10.1 SJC STUDENT COMPLAINTS PROCEDURE 84 2.4 HOUSE COMMITTEE 17 10.2 SJC STUDENT SEXUAL 3. ACADEMIC WORK 19 MISCONDUCT AND SEXUAL 3.1 EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOPHY 19 HARASSMENT POLICY 92 3.2 ACADEMIC POLICIES 19 10.3 PRIVACY POLICY 105 3.3 TUTORIAL PROGRAM 21 11. -

NOVA University of Newcastle Research Online Nova.Newcastle.Edu.Au

NOVA University of Newcastle Research Online nova.newcastle.edu.au McLoughlin, Kcasey; Stenstrom, Hannah; 'Justice Carolyn Simpson and women’s changing place in the legal profession: ‘Yes, you can!’’ Published in Alternative Law Journal Vol. 45, Issue 4, p. 276-283 (2020) Accessed from: https://doi.org/10.1177/1037969X20938203 McLoughlin, K., & Stenstrom, H., Justice Carolyn Simpson and women’s changing place in the legal profession: ‘Yes, you can!’ Alternative Law Journal, 45(4), 276–283. Copyright ©2020. https://doi.org/10.1177/1037969X20938203 Accessed from: http://hdl.handle.net/1959.13/1420869 Justice Carolyn Simpson and women's changing place in the legal profession: ‘Yes, you can!’ Kcasey McLoughlin and Hannah Stenstrom Newcastle Law School, University of Newcastle, Australia Abstract: Justice Carolyn Simpson had a judicial career spanning a quarter of a century – the longest-serving of any of the Supreme Court of New South Wales’ (NSW) women judges. In this article, we critically examine both the image projected at Justice Simpson’s elevation to the Court in 1994 and the legacy crafted about her upon her retirement. As we move forward into a new century of Australian women in law, these speeches reveal much about women’s changing place within the legal profession, but also demonstrate disappointing continuity in terms of the obstacles faced by women. Keywords: Legal profession, gender and the law, gender and judging, women Contributing author: Dr Kcasey McLoughlin, Law School, University of Newcastle, 409 Hunter Street, Newcastle NSW 2300, Australia. In March 2018 Justice Carolyn Simpson retired from the Supreme Court of New South Wales (NSW) after more than two decades on the Bench. -

Summer 2000/2001 Message from the President

CONTENTS Bar News Editor’s note . 2 The JOURNAL of the NSW BAR ASSOCIATION Letters to the Editor. 3 Summer 2000/2001 Message from the President. 4 Editorial Board Recent developments Justin Gleeson S.C. (Editor) Sexual assault communications privilege under siege . 6 Andrew Bell Military Aid to the civil power . 13 James Renwick International perspectives on mandatory sentencing . 16 Chris Winslow Appeals from the Court of Arbitration for Sport . 20 (Bar Association) Opinion Editorial Print/Production Access to quality justice . 22 Rodenprint Interviews Layout The Chief Justice of New South Wales . 25 Hartrick’s Design Office Pty Ltd Jeff Shaw QC returns to the bar . 30 Addresses The inaugural Sir Maurice Byers Lecture. 32 The Hon. R J Ellicott QC: 50 years at the Bar . 39 20 years at the NSW Land & Environment Court . 47 Around the Chambers Opening of Maurice Byers Chambers . 51 Appointments Judicial appointments . 53 Senior counsel . 54 ISSN 0817-002 Vale Views expressed by contributors to Bar Peter Seery . 55 News are not necessarily those of the Bar Association of NSW. Features Contributions are welcome and should Barristers’ Benevolent Association . 55 be addressed to the Editor, Justin Barristers hockey match . 57 Gleeson S.C., 7th Floor, Wentworth 58 Chambers, 180 Phillip Street, Sydney, Bench & Bar v Solicitors chess match . NSW 2000. DX 399 Sydney or email: [email protected] Book reviews . 59 Barristers wishing to join the Editorial Committee are invited to write to the Editor indicating the areas in which they are interested in assisting. 1 C O N T E N T S Bar News Editor’s note . -

Doing Their Bit': New South Wales Barristers in The

1 Doing Their Bit’: New South Wales Barristers in the Second World War Tony Cunneen Draft for comments A Project for the Francis Forbes Society for Australian Legal History Comments and further material welcome Please contact [email protected] His Honour Des Ward (right) with his cousin on Bougainville 1945 (Courtesy Des Ward) . The author invites any people with more photos or information concerning Barristers who served in the war to pass them on for inclusion in the project. 2 A Note on Sources It has been a challenge tracking down details of people some 65 years after the end of the war. The first stage was to generate an Honour Roll. Initially I used lists in the Law Almanac from 1943/1944 which published basic details of those Barristers and solicitors who had served in the armed forces. Many men who were subsequently admitted to the Bar also served and I have included them as well. Their names were initially located by matching lists from the post war Law Almanacs with Databases of service personnel. Searching through the database of the State Archives and then the Law Almanac gave many names and details of men who went on to become Queens Counsel or served on the bench. Many generous members of the Bar and the Judiciary (too many to mention here, but they are much appreciated) as well as the general public supplied further details in response to public requests for information through Bar Brief and the RSVP section of the Sydney Morning Herald. Eventually information came from around Australia and overseas, including Hawaii and Istanbul in Turkey. -

![Serial Liars by Evan Whittonserial-Liars Ebook[1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0268/serial-liars-by-evan-whittonserial-liars-ebook-1-4300268.webp)

Serial Liars by Evan Whittonserial-Liars Ebook[1]

Evan Whitton received the Walkley Award for National Journalism five times and was Journalist of the Year 1983 for ‘courage and innovation’ in reporting a corruption inquiry. He was editor of The National Times, Chief Reporter and European Correspondent for The Sydney Morning Herald, and Reader in Journalism at the University of Queensland. He is now a columnist on the online legal journal, Justinian. www.justinian.com.au Praise for Evan Whitton’s Work ‘Whitton QC not here? What a pity.’ - NSW Premier Neville Wran QC, 1983 “Evan Whitton is exactly the right person to write about any subject that interests him, because of the rare insight that sets him apart from all other Australian journalists.” - Michael English, 1987 Can of Worms (1986) ‘No decent person could read it without being possessed of utter rage at the way our public institutions have been corrupted over the past 15 years or so by criminal elements in politics, the police and even the courts.’ - Senator (Australia) John Stone. Amazing Scenes (1987) ‘... combines literary elegance with real sinew.’ - Denis Butler, The Newcastle Herald ‘Australia’s premier journalist …’ - Mike Ryan, Sunday Press, Melbourne The Hillbilly Dictator (1989) ‘ ... compelling reading, a popular history with a light touch but a serious moral message ... a wealth of anecdotes, humorous, scandalous, shocking, surprising ...’ - Dr Mark Finnane, The Sydney Morning Herald ‘Evan Whitton is a dazzling writer, incisive and addictive; a master journalist, prodigious in his knowledge and effort.’ - Dr George Miller, film director. ‘The Whitton wit is evident … but the tragedy of it all was also evident to him.’ - Christopher Masters, The Herald, Melbourne 2 Trial by Voodoo (1994) ‘The only book in the language that critically examines the law as a whole.’ - Law Professor Alex Ziegert, University of Sydney. -

Albury & District Historical Society Inc October 2019 No

Albury & District Historical Society Inc October 2019 No 605 PO Box 822 ALBURY 2640 https://alburyhistory.org.au/ For Your Reference A&DHS account details are: BSB 640 000 Acc No 111097776 Registered by Australia Post PP 225170/0019 ISSN 2207-1237 Next Meeting Wednesday, October 9 7.30 pm, Commercial Club Integrating recently arrived refugees into our local community. Speaker: Dr Penny Vine Albury LibraryMuseum Albury & Australia’s Dutch Connections Until December 15 Page 2 Growing up Dutch Page 3 First Newspapers Page 5 Did You Know The Dutch Block at Bonegilla Reception Centre, 1955 Page 5 History News Page 7 Wm & Mary Brickell REPORT ON SEPTEMBER MEETING (11.09.2019) Our September meeting heard from Chris de Vreeze talking about his arrival in Australia with his family in 1952 as a young boy and Dutch immigrant, coming through the Bonegilla Reception Centre and then growing up in Albury. We had a large number of guests from the local Dutch community and several made their own contribution to the story of the Dutch in our local area. Museum curator Emma Williams then gave us a quick preview of what to expect when the exhibition ‘Albury & Australia’s Dutch Connections’ gets under way at Albury Library Museum on September 28. President Greg Ryan informed the meeting that Albury City Council has made it known that the owners of ‘Meramie’ at 595 Kiewa St have submitted revised plans for demolition and then residential development on the site. Our submission in 2018 opposing the first development application was significant in saving the historic building. -

BORROWED SCENERY SCHOOLS RESOURCE the Following Material Is Provided for High School Teachers, and Can Be Copied Or Adopted to Suit Student Ages and Subject Needs

BORROWED SCENERY SCHOOLS RESOURCE The following material is provided for high school teachers, and can be copied or adopted to suit student ages and subject needs. This resource offers an overview of the exhibition and key curatorial themes, as well as providing contextual information and suggested questions, for a small selection of works in the exhibition. For school excursions, in-school program options and enquiries, please contact: Edwina Hill Education Officer Campbelltown Arts Centre [email protected] (02) 4645 4298 Cover Image: Fiona Lowry I’m your kind, I’m your kind and I see 2006 Acrylic and gouache on canvas 167 x 152cm Image courtesy of the artist and Jan Murphy Gallery Photograph by Stephen Oxenbury 2 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 5 LABOUR AND BLISS, DOMESTICITY – “PERSONAL IS 6 POLITICAL” CHRISTINE DEAN 7 JOAN ROSS 8 KATTHY CAVALIERE 10 WOMEN’S BUSINESS 12 YVONNE KOOLMATRIE 12 ROSALIE GASCOIGNE 14 ELISABETH CUMMINGS 15 GLORIA PETYARRE 17 A SATURATED TERRAIN 19 BARBARA CLEVELAND 20 DEBORAH KELLY 21 TRACEY MOFFATT 23 WHERE IT COUNTS: COUNTESS AND ART AS A TOOL 26 FOR SOCIAL CHANGE COUNTESS REPORT 27 3 4 INTRODUCTION: BORROWED SCENERY WEDNESDAY 2 JANUARY – SUNDAY 10 MARCH, 2019 INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S DAY CLOSING EVENT, 6 – 8PM FRIDAY 8 MARCH, 2019 For centuries, women have been subjects for male artists, Image on previous page: inserted into scenes framed by the male gaze. Borrowed Scenery Borrowed Scenery. Installation view, Campbelltown Arts explores what happens when the subjects of this gaze look Centre, 2019. back, step outside the frame, and assert their own vision and experience of the world.