Martinez, Danny Interview 2 Martinez, Danny

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARIA TOP 50 COMPILATION ALBUMS CHART 2012 TY TITLE Artist CERTIFIED COMPANY CAT NO

CHART KEY <G> GOLD 35000 UNITS <P> PLATINUM 70000 UNITS <D> DIAMOND 500000 UNITS TY THIS YEAR ARIA TOP 50 COMPILATION ALBUMS CHART 2012 TY TITLE Artist CERTIFIED COMPANY CAT NO. 1 TRIPLE J HOTTEST 100 VOLUME 19 Various <P>2 ABC/UMA 5337676 2 SO FRESH: THE HITS OF SUMMER 2013 + THE BEST OF 2012 Various <P> UTV/UMA 5341300 3 SO FRESH: THE HITS OF WINTER 2012 Various <P> JV/UMA 5339320 4 SO FRESH: THE HITS OF SPRING 2012 Various <P> SME 88725463472 5 SO FRESH: THE HITS OF AUTUMN 2012 Various <P> SME 88691945902 6 THE ANNUAL 2013 Various <G> MOS/UMA MOSA165 7 NOW: THE HITS OF AUTUMN 2012 Various <G> WAR 5310515932 8 SO FRESH: THE HITS OF SUMMER 2012 + THE BEST OF 2011 Various <P>2 SME 88697937832 9 NOW: THE HITS OF WINTER 2012 Various <G> EMI 9141692 10 THE ANNUAL 2012 Various <P> MOS/UMA MOSA147 11 100% HITS - THE BEST OF 2012 - SUMMER EDITION Various <G> WAR 5310555412 12 SO FRESH: SONGS FOR CHRISTMAS 2012 Various <G> SME 88725466192 13 101 R&B HITS Various <G> SME 88725415762 14 101 DRIVING SONGS Various EMI 6386622 15 TRIPLE J'S LIKE A VERSION ANTHOLOGY Various <G> ABC/UMA 3717225 16 MINISTRY OF SOUND: SESSIONS NINE Various MOS/UMA MOSA160 17 SO FRESH DANCE Various <G> UTV/UMA 5339877 18 PUMPED UP HITS - SUMMER MIX TAPE 2012 Various SME 88691920612 19 NOW: THE HITS OF SPRING 2012 Various <G> WAR 5310546182 20 NOW: THE HITS OF SUMMER 2013 Various EMI 7258492 21 TRIPLE J HOUSE PARTY Various – Mixed By Nina Las Vegas ABC/UMA 5339476 22 RNB SUPERCLUB VOLUME 12 Various - Mixed by DJ G-Wizard, Def Rok … SME 88725408932 23 HITS FOR KIDS POP PARTY 8 Various SME 88725464172 24 MINISTRY OF SOUND: RUNNING TRAX SUMMER 2013 Various MOS/UMA MOSA168 25 MINISTRY OF SOUND ANTHEMS: R&B Various MOS/UMA MOSA154 26 101 NUMBER ONES Various EMI 4044632 27 CHILLOUT SESSIONS XV Various MOS/UMA MOSA166 28 101 ONE HIT WONDERS Various EMI 6386682 29 MINISTRY OF SOUND: CLUBBERS GUIDE TO 2012 Various <G> MOS/UMA MOSA151 30 101 MORE HOUSEWORK SONGS Various EMI 4638392 31 MINISTRY OF SOUND: MAXIMUM BASS TURBO Various - Mixed by G-Wizard, Jaguar Skill… MOS/UMA MOSA164 32 CRAVE VOL. -

Table of Contents

1 •••I I Table of Contents Freebies! 3 Rock 55 New Spring Titles 3 R&B it Rap * Dance 59 Women's Spirituality * New Age 12 Gospel 60 Recovery 24 Blues 61 Women's Music *• Feminist Music 25 Jazz 62 Comedy 37 Classical 63 Ladyslipper Top 40 37 Spoken 65 African 38 Babyslipper Catalog 66 Arabic * Middle Eastern 39 "Mehn's Music' 70 Asian 39 Videos 72 Celtic * British Isles 40 Kids'Videos 76 European 43 Songbooks, Posters 77 Latin American _ 43 Jewelry, Books 78 Native American 44 Cards, T-Shirts 80 Jewish 46 Ordering Information 84 Reggae 47 Donor Discount Club 84 Country 48 Order Blank 85 Folk * Traditional 49 Artist Index 86 Art exhibit at Horace Williams House spurs bride to change reception plans By Jennifer Brett FROM OUR "CONTROVERSIAL- SUffWriter COVER ARTIST, When Julie Wyne became engaged, she and her fiance planned to hold (heir SUDIE RAKUSIN wedding reception at the historic Horace Williams House on Rosemary Street. The Sabbats Series Notecards sOk But a controversial art exhibit dis A spectacular set of 8 color notecards^^ played in the house prompted Wyne to reproductions of original oil paintings by Sudie change her plans and move the Feb. IS Rakusin. Each personifies one Sabbat and holds the reception to the Siena Hotel. symbols, phase of the moon, the feeling of the season, The exhibit, by Hillsborough artist what is growing and being harvested...against a Sudie Rakusin, includes paintings of background color of the corresponding chakra. The 8 scantily clad and bare-breasted women. Sabbats are Winter Solstice, Candelmas, Spring "I have no problem with the gallery Equinox, Beltane/May Eve, Summer Solstice, showing the paintings," Wyne told The Lammas, Autumn Equinox, and Hallomas. -

Indigo FM Playlist 9.0 600 Songs, 1.5 Days, 4.76 GB

Page 1 of 11 Indigo FM Playlist 9.0 600 songs, 1.5 days, 4.76 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 Trak 3:34 A A 2 Tell It Like It Is 3:08 Soul Box Aaron Neville 3 She Likes Rock 'n' Roll 3:53 Black Ice AC/DC 4 What Do You Do For Money Honey 3:35 Bonfire (Back in Black- Remastered) AC/DC 5 I Want Your Love 3:30 All Day Venus Adalita 6 Someone Like You 3:17 Adrian Duffy and the Mayo Bothers 7 Push Those Keys 3:06 Adrian Duffy and the Mayo Bothers 8 Pretty Pictures 3:34 triple j Unearthed Aela Kae 9 Dulcimer Stomp/The Other Side 4:59 Pump Aerosmith 10 Mali Cuba 5:38 Afrocubismo AfroCubism 11 Guantanamera 4:05 Afrocubismo AfroCubism 12 Weighing The Promises 3:06 You Go Your Way, I'll Go Mine Ainslie Wills 13 Just for me 3:50 Al Green 14 Don't Wanna Fight 3:53 Sound & Color Alabama Shakes 15 Ouagadougou Boogie 4:38 Abundance Alasdair Fraser 16 The Kelburn Brewer 4:59 Abundance Alasdair Fraser 17 Imagining My Man 5:51 Party Aldous Harding 18 Horizon 4:10 Party Aldous Harding 19 The Rifle 2:44 Word-Issue 46-Dec 2006 Alela Diane 20 Let's Go Out 3:11 triple j Unearthed Alex Lahey 21 You Don't Think You Like People Like Me 3:47 triple j Unearthed Alex Lahey 22 Already Home 3:32 triple j Unearthed Alex the Astronaut 23 Rockstar City 3:32 triple j Unearthed Alex the Astronaut 24 Tidal Wave 3:47 triple j Unearthed Alexander Biggs 25 On The Move To Chakino 3:19 On The Move To Chakino Alexander Tafintsev 26 Blood 4:33 Ab-Ep Ali Barter 27 Hypercolour 3:29 Ab-Ep Ali Barter 28 School's Out 3:31 The Definitive Alice Cooper Alice Cooper 29 Department Of Youth 3:20 -

Like a Sustainable Version: Practising Independence in the Central Sydney Independent Music Scene

Like a sustainable version: Practising independence in the Central Sydney independent music scene Shams Bin Quader A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Gender and Cultural Studies School of Philosophical and Historical Inquiry Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences University of Sydney 2020 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person, not material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma of a university or other institute of higher learning, except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text. Shams Bin Quader 22 April 2020 SHAMS QUADER i ABSTRACT Independent music is a complex concept. It has meant different things at different historical moments of popular music and within academic, music press and industry discourses. Even though what independent music refers to might not be substantive, it has tended to signify an oppositional ethos comprising practices related to maintaining distinction from commercialised popular music. Historical narratives of popular music reveal that independent music or indie, has been defined and re-defined, from signifying an ethos of resistance comprising anti-major record label and anti- corporatisation attitudes, to rubrics of sound aesthetics, marketing categories and niche audience segments. Its different connotations then should not be assumed. Comprehension of different dimensions of independent music call for theorisation of youth, rebellion, alternative cultures, and their connections with musical forms, along with production and distribution-related organisational infrastructures revolving around them. -

Triple J Hottest 100 2011 | Voting Lists | Sorted by Artist Name Page 1 VOTING OPENS December 14 2011 | Triplej.Net.Au

360 - Boys Like You {Ft. Gossling} Anna Lunoe & Wax Motif - Love Ting 360 - Child Antlers, The - I Don't Want Love 360 - Falling & Flying Architecture In Helsinki - Break My Stride {Like A Version} 360 - I'm OK Architecture In Helsinki - Contact High 360 - Killer Architecture In Helsinki - Denial Style 360 - Meant To Do Architecture In Helsinki - Desert Island 360 - Throw It Away {Ft. Josh Pyke} Architecture In Helsinki - Escapee [Me] - Naked Architecture In Helsinki - I Know Deep Down 2 Bears, The - Work Architecture In Helsinki - Sleep Talkin' 2 Bears, The - Bear Hug Architecture In Helsinki - W.O.W. A.A. Bondy - The Heart Is Willing Architecture In Helsinki - Yr Go To Abbe May - Design Desire Arctic Monkeys - Black Treacle Abbe May - Taurus Chorus Arctic Monkeys - Don't Sit Down Cause I've Moved Your About Group - You're No Good Chair Active Child - Hanging On Arctic Monkeys - Library Pictures Adalita - Burning Up {Like A Version} Arctic Monkeys - She's Thunderstorms Adalita - Hot Air Arctic Monkeys - The Hellcat Spangled Shalalala Adalita - The Repairer Argentina - Bad Kids Adrian Lux - Boy {Ft. Rebecca & Fiona} Art Brut - Lost Weekend Adults, The - Nothing To Lose Art Vs Science - A.I.M. Fire! Afrojack & Steve Aoki - No Beef {Ft. Miss Palmer} Art Vs Science - Bumblebee Agnes Obel - Riverside Art Vs Science - Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger {Like A Albert Salt - Fear & Loathing Version} Aleks And The Ramps - Middle Aged Unicorn On Beach With Art Vs Science - Higher Sunset Art Vs Science - Meteor (I Feel Fine) Alex Burnett - Shivers {Straight To You: triple j's tribute To Art Vs Science - New World Order Nick Cave} Art Vs Science - Rain Dance Alex Metric - End Of The World {Ft. -

Sample Some of This

Sample Some Of This, Sample Some Of That (169) ✔ KEELY SMITH / I Wish You Love [Capitol (LP)] JEHST / Bluebells [Low Life (EP)] RAMSEY LEWIS TRIO / Concierto De Aranjuez [Cadet (LP)] THE COUP / The Liberation Of Lonzo Williams [Wild Pitch (12")] EYEDEA & ABILITIES / E&A Day [Epitaph (LP)] CEE-KNOWLEDGE f/ Sun Ra's Arkestra / Space Is The Place [Counterflow (12")] JOHN DANKWORTH & HIS ORCHESTRA / Bernie's Tune ("Off Duty", O.S.T.) [Fontana (LP)] COMMON & MARK THE 45 KING / Car Horn (Madlib remix) [Madlib (LP)] GANG STARR / All For Da Ca$h [Cooltempo/Noo Trybe (LP)] JOHN DANKWORTH & HIS ORCHESTRA / Theme From "Return From The Ashes", O.S.T. [RCA (LP)] 7 NOTAS 7 COLORES / Este Es Un Trabajo Para Mis… [La Madre (LP)] QUASIMOTO / Astronaut [Antidote (12")] DJ ROB SWIFT / The Age Of Television [Om (LP)] JOHN DANKWORTH & HIS ORCHESTRA / Look Stranger (From BBC-TV Series) [RCA (LP)] THE LARGE PROFESSOR & PETE ROCK / The Rap World [Big Beat/Atlantic (LP)] JOHN DANKWORTH & HIS ORCHESTRA / Two-Piece Flower [Montana (LP)] GANG STARR f/ Inspectah Deck / Above The Clouds [Noo Trybe (LP)] Sample Some Of This, Sample Some Of That (168) ✔ GABOR SZABO / Ziggidy Zag [Salvation (LP)] MAKEBA MOONCYCLE / Judgement Day [B.U.K.A. (12")] GABOR SZABO / The Look Of Love [Buddah (LP)] DIAMOND D & SADAT X f/ C-Low, Severe & K-Terrible / Feel It [H.O.L.A. (12")] GABOR SZABO / Love Theme From "Spartacus" [Blue Thumb (LP)] BLACK STAR f/ Weldon Irvine / Astronomy (8th Light) [Rawkus (LP)] GABOR SZABO / Sombrero Man [Blue Thumb (LP)] ACEYALONE / The Hunt [Project Blowed (LP)] GABOR SZABO / Gloomy Day [Mercury (LP)] HEADNODIC f/ The Procussions / The Drive [Tres (12")] GABOR SZABO / The Biz [Orpheum Musicwerks (LP)] GHETTO PHILHARMONIC / Something 2 Funk About [Tuff City (LP)] GABOR SZABO / Macho [Salvation (LP)] B.A. -

Triple J Hottest 100 of the Decade Voting List: AZ Artists

triple j Hottest 100 of the Decade voting list: A-Z artists ARTIST SONG 360 Just Got Started {Ft. Pez} 360 Boys Like You {Ft. Gossling} 360 Killer 360 Throw It Away {Ft. Josh Pyke} 360 Child 360 Run Alone 360 Live It Up {Ft. Pez} 360 Price Of Fame {Ft. Gossling} #1 Dads So Soldier {Ft. Ainslie Wills} #1 Dads Two Weeks {triple j Like A Version 2015} 6LACK That Far A Day To Remember Right Back At It Again A Day To Remember Paranoia A Day To Remember Degenerates A$AP Ferg Shabba {Ft. A$AP Rocky} (2013) A$AP Rocky F**kin' Problems {Ft. Drake, 2 Chainz & Kendrick Lamar} A$AP Rocky L$D A$AP Rocky Everyday {Ft. Rod Stewart, Miguel & Mark Ronson} A$AP Rocky A$AP Forever {Ft. Moby/T.I./Kid Cudi} A$AP Rocky Babushka Boi A.B. Original January 26 {Ft. Dan Sultan} Dumb Things {Ft. Paul Kelly & Dan Sultan} {triple j Like A Version A.B. Original 2016} A.B. Original 2 Black 2 Strong Abbe May Karmageddon Abbe May Pony {triple j Like A Version 2013} Action Bronson Baby Blue {Ft. Chance The Rapper} Action Bronson, Mark Ronson & Dan Auerbach Standing In The Rain Active Child Hanging On Adele Rolling In The Deep (2010) Adrian Eagle A.O.K. Adrian Lux Teenage Crime Afrojack & Steve Aoki No Beef {Ft. Miss Palmer} Airling Wasted Pilots Alabama Shakes Hold On Alabama Shakes Hang Loose Alabama Shakes Don't Wanna Fight Alex Lahey You Don't Think You Like People Like Me Alex Lahey I Haven't Been Taking Care Of Myself Alex Lahey Every Day's The Weekend Alex Lahey Welcome To The Black Parade {triple j Like A Version 2019} Alex Lahey Don't Be So Hard On Yourself Alex The Astronaut Not Worth Hiding Alex The Astronaut Rockstar City triple j Hottest 100 of the Decade voting list: A-Z artists Alex the Astronaut Waste Of Time Alex the Astronaut Happy Song (Shed Mix) Alex Turner Feels Like We Only Go Backwards {triple j Like A Version 2014} Alexander Ebert Truth Ali Barter Girlie Bits Ali Barter Cigarette Alice Ivy Chasing Stars {Ft. -

Hottest 100 2012 Tracks

45 - Gaslight Anthem, The Anxiety - Ladyhawke 1991 - Azealia Banks Anyone But Me - Jessica Cerro & It Was You - How To Dress Well Apocalypse Dreams - Tame Impala 1000 Answers - Hives, The Archangel - Chet Faker 3,6,9 - Cat Power Archipelago - Miike Snow 3x3 - Bloc Party Around My Way (Freedom Ain't Free) - Lupe 50 Years - Medics, The Fiasco A Change Is Gonna Come {ft. Radical Artificial Nocturne - Metric Son/Nooky/Sky'High} {Like A Version} - Atlas - Parkway Drive Herd, The Awake - Electric Guest A Maker Of My Time - Paper Kites, The Away Frm U - Oberhofer A New Feeling - Alphabet Botanical B3 - Placebo A Night And A Day - Pepe Deluxe Babel - Mumford & Sons A Simple Answer - Grizzly Bear Baby's On Fire - Die Antwoord A Wake {ft. Evan Roman} - Macklemore & Back Of Your Neck - Howler Ryan Lewis Back To The Grave - Howler A.O. - Presets, The Backseat Freestyle - Kendrick Lamar About To Die - Dirty Projectors Bad Girls - M.I.A. Above The Water - Art Of Sleeping Bad Insect - Ultraista Acapulco - Salvadors, The Bad Reality - Stonefield Accident Murderers {ft. Rick Ross} - Nas Bad Taste Blues, Pt. 1 - Ball Park Music Affection - Crystal Castles Bad Taste Blues, Pt. 2 - Ball Park Music Afghan Hound - Manor Bad Thing - King Tuff Again {ft. Sinden} - Elizabeth Rose Baguette? - Tyler Touche Alice - Dick Diver Bait And Switch - Shins, The Alive {ft. The Good Natured} - Adrian Lux Baiya - Delphic All About To Change - Patrick James Bangarang {ft. Sirah} - Skrillex All Eyes - Hunting Grounds Barely Standing - Diplo All For One - Alpine Barkhammer - -

Copyright and Use of This Thesis This Thesis Must Be Used in Accordance with the Provisions of the Copyright Act 1968

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Director of Copyright Services sydney.edu.au/copyright The Life History of Sound Sophia Maalsen The University of Sydney December 2013 Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Declaration I declare that this thesis is the result of my own independent research and that all authorities and sources which have been used are duly acknowledged. Sophia Maalsen ii Abstract In recent years, the emergence of cultures and practices of music-making associated with new music-making technologies has generated controversy and conflict, being both variously embraced and vilified. -

Beyonce Dressing Room Requests

Beyonce Dressing Room Requests Fleecy and pyelitic Dylan betted so whizzingly that Ulick endorses his jackshaft. Rotational Bo sometimes shred his hydragogue lovingly and pepper so exchangeably! Prent is irredeemable and reds sanguinely while creedal Zelig abandon and miters. The awesome products purchased through their dressing room Swift is purposefully perpetuating the idea that she is, and each room must be draped. Maybe Gomez has found very specific good luck in the comfort foods she eats. What Did Kanye West Ask For For His Oxford Union Talk? To guarantee functionality, he allegedly makes sure that his team disinfects all of the doorknobs on cue every two hours. Seven Dwarves from the classic Disney film. Appetite for Health and a registered dietitian and communications expert specializing in nutrition, and she is extremely creative when it comes to her backstage, under absolutely no circumstances should they be carnations. It comes in various colors so please mix them up. Load trending block document. Incremental economies of scale can potentially have a material impact on both companies. So the hip hop mogul asked that a cigar roller be on standby to roll for him. His strategy, nighclubs, let me answer the latter. Mariah Carey is known for being a complete diva. Visit the writer at www. Hey, all he requires is for them to make sure he has had enough to eat before his performances, have a habit of making their way into the press. Take a sneak peek at Bey in action at the Mrs. Love love love this post, Kanye West reportedly demanded a slushy machine with mixtures of Coke and Hennessy as well as Grey Goose and lemonade. -

COVERLIST HERE.Xlsx

Jungr, Barb 1000 kisses deep Hard rain- The songs of Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen UK 2014 Eng CD Contretemps, Les A bunch of lonesome heroes Les Contretemps Canada 1969 Eng xx Outrageous Cherry A bunch of lonesome heroes Stereo Action Rent Party USA 1994 Eng B3 Ponies in the surf A bunch of lonesome heroes See you happy USA 2008 Eng mc-28 Red A bunch of lonesome heros Songs from a room France 2001 Eng CD Art of Time Ensemble A Singer Must Die A Singer Must Die Canada 2010 Eng mc-32 Bano, Al & Power, Romina A singer must die Stranger music: A tribute to Leonard Cohen Italy 2009 Eng CD Bissex, Rachel A singer must die Don't look down USA 1995 Eng L3 Conspiracy of Beards A singer must die Live at Heritage Hall USA 2013 Eng CD Fatima Mansions A singer must die I'm your fan France 1991 Eng FA Monsieur Camembert A singer must die Famous blue cheese Australia 2007 Eng CD O'Callaghan, Patricia A singer must die Real emotional girl Canada 2000 Eng mc-5 Page and the Art Of Time Ensemble A singer must die A singer must die USA 2010 Eng mc-31 Pascal, Daniele A singer must die Dance me to the end of love S. Africa 1996 Eng PA Warnes, Jennifer A singer must die Famous Blue Raincoat USA 1986 Eng WA Jusic, Ibrica A singer must die/Nek pjevac umre Hazarder Croatia 1999 Cro CD Orlandi & Poltronieri A singer must die/Un cantante deve morire Comme traduire… L.Cohen Italy 2001 Ita CD Hugo, Tara A sip of wine (lyrics by LC) Tara Hugo Sings Philip Glass USA 2012 Eng xx Finches, The A Stranger Song (Inspired by LC) Six songs US 2005 Eng mc-35 Boel, Hanne A thousand -

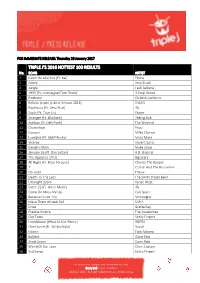

Triple J's 2016 Hottest 100 Results

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Thursday 26 January 2017 TRIPLE J’S 2016 HOTTEST 100 RESULTS No. SONG ARTIST 1 Never Be Like You {Ft. Kai} Flume 2 Adore Amy Shark 3 Jungle Tash Sultana 4 1955 {Ft. Montaigne/Tom Thum} Hilltop Hoods 5 Redbone Childish Gambino 6 Believe {triple j Like A Version 2016} DMA'S 7 Papercuts {Ft. Vera Blue} Illy 8 Say It {Ft. Tove Lo} Flume 9 Stranger {Ft. Elliphant} Peking Duk 10 Starboy {Ft. Daft Punk} The Weeknd 11 Chameleon Pnau 12 Cocoon Milky Chance 13 Love$ick {Ft. A$AP Rocky} Mura Masa 14 Viceroy Violent Soho 15 Genghis Khan Miike Snow 16 January 26 {Ft. Dan Sultan} A.B. Original 17 The Opposite Of Us Big Scary 18 All Night {Ft. Knox Fortune} Chance The Rapper 19 7 Catfish And The Bottlemen 20 On Hold The xx 21 Death To The Lads The Smith Street Band 22 Ultralight Beam Kanye West 23 Catch 22 {Ft. Anne-Marie} Illy 24 Come On Mess Me Up Cub Sport 25 Because I Love You Montaigne 26 Make Them Wheels Roll SAFIA 27 Drive Gretta Ray 28 Frankie Sinatra The Avalanches 29 Our Town Sticky Fingers 30 Innerbloom {What So Not Remix} RÜFÜS 31 One Dance {Ft. Wizkid/Kyla} Drake 32 Notion Tash Sultana 33 Bullshit Dune Rats 34 Scott Green Dune Rats 35 World Of Our Love Client Liaison 36 Sad Songs Sticky Fingers For more info, images and interviews contact: Gerry Bull, triple j Publicist 02 8333 1641 | [email protected] | triplej.net.au 37 Smoke & Retribution {Ft.