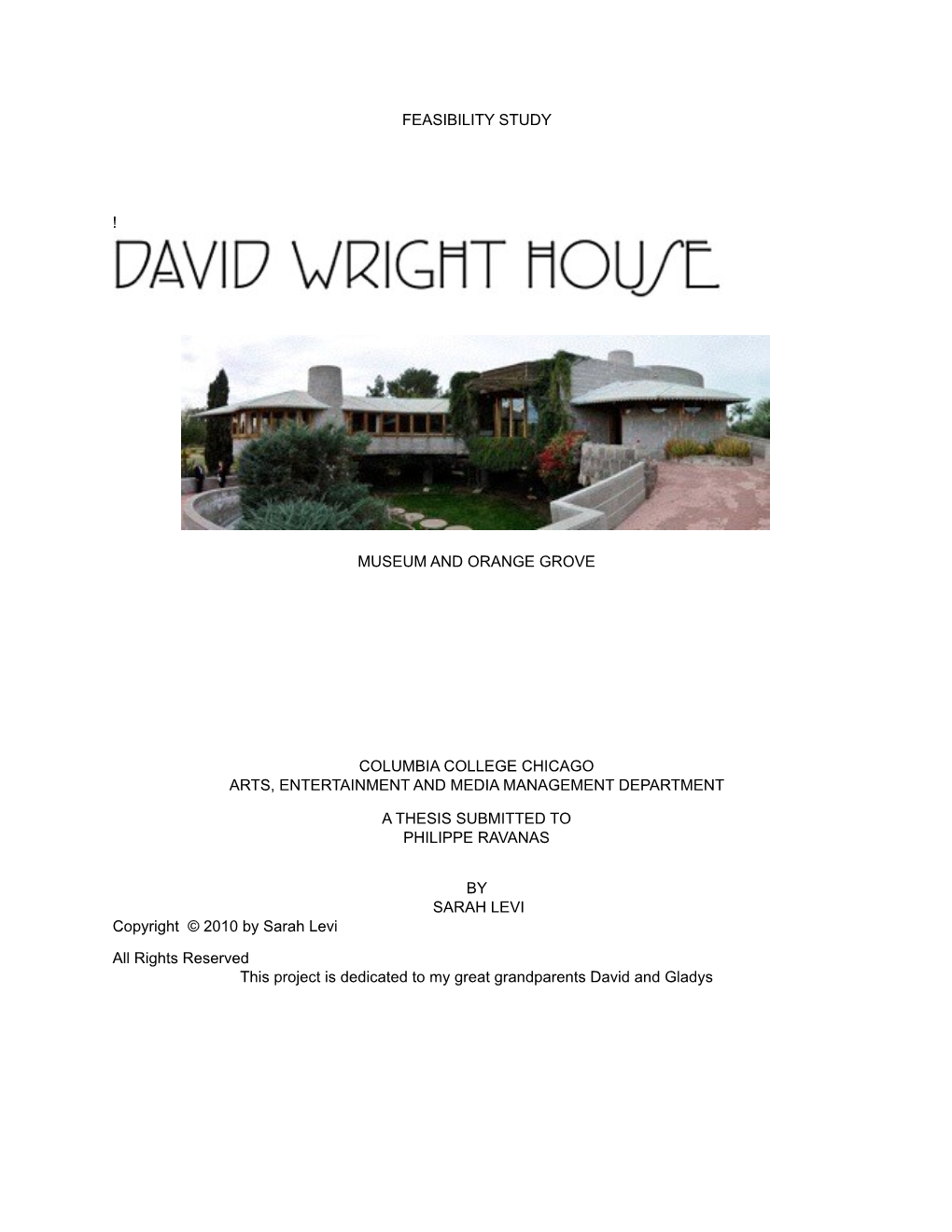

David Wright House Sarah-Levi-Masters-Thesis 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phoenix Area Homes Include the Circular David Wright House (1952), 5212 East Exeter Blvd., Designed for His Son in North Phoenix (1950), and the H.C

CITY REPORT (Iraq) Opera House (never built), serves as a distinguished gateway to the Tempe campus of Arizona State University. Its president at the time, Grady Gammage, was a good friend of the architect. Wright’s First Christian Church (designed in 1948/built posthumously by the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation in 1973), 6750 N. Seventh Ave., incorporates desert masonry, as in Taliesin West, and features distinctive spires. Wright’s ten distinguished Phoenix area homes include the circular David Wright House (1952), 5212 East Exeter Blvd., designed for his son in north Phoenix (1950), and the H.C. Price House (1954), 7211 N. Tatum Blvd., with its graceful combination of concrete block, steel and copper in a foothills setting. Wright’s approach continued through his pupils, such as Albert Chase McArthur, who is generally credited with the design of the spectacular Arizona Biltmore Hotel (1928), 24th St. and Missouri Ave. Wright’s influence on the building is clear in both massing and details, including the distinctive concrete Biltmore Blocks, cast onsite to an Emry Kopta design. The hotel was Foundation. Photo by Lara Corcoran, courtesy Frank Lloyd Wright restored after a fire in 1973, and additions were built in 1975 and 1979. Blaine Drake was another student who, with Alden Dow, designed the original Phoenix Art Museum, Theater and Library Complex and East Wing (1959, 1965), 1625 N. Central Ave. (Tod Williams and Billie Tsien Architects, New York, designed additions in 1996 and 2006.) Drake also designed the first addition to the Heard Museum (1929), 22 E. Monte Vista Rd., a PHOENIX: UP FROM THE DESERT Spanish Colonial Revival by H.H. -

V'zot Haberacha

Parshah V’Zot HaBeracha B”H In a Nutshell The Parshah in a Nutshell V’Zot HaBeracha (Deut.33:1-34:12) and the Sukkot Torah readings The Sukkot and Shemini Atzeret Torah readings are describing G-d's creation of the world in six from Leviticus 22-23, Numbers 29, and Deuteronomy days and His ceasing work on the seventh-- 14-16. These readings detail the laws of the moadim which He sanctified and blessed as a day of or "appointed times" on the Jewish calendar for rest. festive celebration of our bond with G-d; including the mitzvot of dwelling in the sukkah (branch-covered hut) and taking the "Four Kinds" on the festival of Sukkot; the offerings brought in the Holy Temple in Jerusalem on Sukkot, and the obligation to journey to the Holy Temple to "to see and be seen before the face of G-d" on the three annual pilgrimage festivals -- Passover, Shavuot and Sukkot. On Simchat Torah ("Rejoicing of the Torah") we conclude, and begin anew, the annual Torah-reading cycle. First we read the Torah section of Vezot Haberachah, which recounts the blessings that Moses gave to each of the twelve tribes of Israel before his death. Echoing Jacob's blessings to his twelve sons five generations earlier, Moses assigns and empowers each tribe with its individual role within the community of Israel. Vezot Haberachah then relates how Moses ascended Mount Nebo from whose summit he saw the Promised Land. "And Moses the servant of G-d died there in the Land of Moab by the mouth of G-d.. -

Free Land Attracted Many Colonists to Texas in 1840S 3-29-92 “No Quitting Sense” We Claim Is Typically Texas

“Between the Creeks” Gwen Pettit This is a compilation of weekly newspaper columns on local history written by Gwen Pettit during 1986-1992 for the Allen Leader and the Allen American in Allen, Texas. Most of these articles were initially written and published, then run again later with changes and additions made. I compiled these articles from the Allen American on microfilm at the Allen Public Library and from the Allen Leader newspapers provided by Mike Williams. Then, I typed them into the computer and indexed them in 2006-07. Lois Curtis and then Rick Mann, Managing Editor of the Allen American gave permission for them to be reprinted on April 30, 2007, [email protected]. Please, contact me to obtain a free copy on a CD. I have given a copy of this to the Allen Public Library, the Harrington Library in Plano, the McKinney Library, the Allen Independent School District and the Lovejoy School District. Tom Keener of the Allen Heritage Guild has better copies of all these photographs and is currently working on an Allen history book. Keener offices at the Allen Public Library. Gwen was a longtime Allen resident with an avid interest in this area’s history. Some of her sources were: Pioneering in North Texas by Capt. Roy and Helen Hall, The History of Collin County by Stambaugh & Stambaugh, The Brown Papers by George Pearis Brown, The Peters Colony of Texas by Seymour V. Conner, Collin County census & tax records and verbal history from local long-time residents of the county. She does not document all of her sources. -

The Lists of the Twelve Tribes

225 THE LISTS OF THE TWELVE TRIBES. THE twelve " sons " of Jacob, or the twelve tribes of Israel, are mentioned together and by name some twenty times in the Old Testament and once in the New. The contents of these lists vary slightly. At times Levi is one of the twelve, at times not. When Levi is omitted from the list as a tribe apart, the number twelve is completed by dividing Joseph up into Manasseh and Ephraim. This is_ well known. It is less generally observed that in Genesis we have another. early variation : Levi and Joseph both appear, but the twelfth place, subsequently occupied by Benjamin (as yet according to the story unborn), is filled by Jacob's daughter Dinah-a small tribe, as we may con clude, whose misfortunes, related mainly in the form of a. personal narrative 1 in Genesis xxxiv., were followed by early extinction. 2 In Revelation vii. the place left vacant by Dan is filled by Manasseh, though Joseph occurs later in the list. Another curious method of completing the number twelve is found in the book of Jubilees xxxviii. 5ff. ; the place of Joseph, who is absent in Egypt, is there taken by Hanoch, the eldest son of Reuben (cf. Gen. xlvi. 9). The first of the more familiar lists is obtained by com bining Genesis xxix. 31-xxx. 24, and xxxv. 16 ff~ These are the well known narratives of the births of Jacob's children ; and in them the children are naturally men tioned in the exact order of their birth. -

Preserving the Textile Block at Florida Southern College a Report Prepared for the World Monuments Fund Jeffrey M

Preserving the Textile Block at Florida Southern College A Report Prepared for the World Monuments Fund Jeffrey M. Chusid, Preservation Architect 18 September 2009 ISBN-10: 1-890879-43-6 ISBN-13: 978-1-890879-43-3 © 2011 World Monuments Fund 2 Letter from World Monuments Fund President Bonnie Burnham 4 Letter from Florida Southern President Anne B. Kerr, Ph.D. 5 Executive Summary 6 Introduction 7 Preservation Philosophy 7 History and Significance 10 Ideas behind the System 10 Description of the System 10 Conservation Issues with the System in Earlier Sites 13 Recent Conservation Projects at the Storer, Freeman, and Ennis Houses 14 Florida Southern College 16 A History of Changes 18 Site Conditions and Analysis 19 Contents Prior research and observations 19 WMF Site visit 19 Taxonomy of Conservation Problems in the Textile-Block System 20 Issues and Challenges 22 The Textile-Block System 22 The Block 23 Methodologies 24 Conservation 25 Recommendations 26 Appendix A: Visual Conditions Documentation 29 Appendix B: Team Members 38 3 In April 2009, World Monuments Fund was honored to convene a historic gathering of historians, architects, conservators, craftsmen, and scientists at Florida Southern College to explore Frank Lloyd Wright’s use of ornamental concrete textile block construction. To Wright, this material was a highly expressive, decorative, and practical approach to create monumental yet affordable buildings. Indeed, some of his most iconic structures, including the Ennis House in Los Angeles, utilized the textile block system. However, like so many of Wright’s experiments with materials and engineering, textile block has posed major challenges to generations of building owners, architects, and conservators who have struggled with the system’s material and structural performance. -

The Order and Significance of the Sealed Tribes of Revelation 7:4-8

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Master's Theses Graduate Research 2011 The Order and Significance of the Sealed ribesT of Revelation 7:4-8 Michael W. Troxell Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/theses Recommended Citation Troxell, Michael W., "The Order and Significance of the Sealed ribesT of Revelation 7:4-8" (2011). Master's Theses. 56. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/theses/56 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. ABSTRACT THE ORDER AND SIGNIFICANCE OF THE SEALED TRIBES OF REVELATION 7:4-8 by Michael W. Troxell Adviser: Ranko Stefanovic ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Thesis Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: THE ORDER AND SIGNIFICANCE OF THE SEALED TRIBES OF REVELATION 7:4-8 Name of researcher: Michael W. Troxell Name and degree of faculty adviser: Ranko Stefanovic, Ph.D. Date completed: November 2011 Problem John’s list of twelve tribes of Israel in Rev 7, representing those who are sealed in the last days, has been the source of much debate through the years. This present study was to determine if there is any theological significance to the composition of the names in John’s list. -

Examining the Us Dairy Industry's Control Over

THE WOLVES ARE GUARDING THE COW PASTURE: EXAMINING THE U.S. DAIRY INDUSTRY’S CONTROL OVER THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT By Benjamin Levi DeVore Submitted to Central European University School of Public Policy in partial fulfilment for the degree of Master of Arts in Public Policy CEU eTD Collection Supervisor: Evelyne Hübscher Budapest, Hungary 2020 Author’s Declaration I, the undersigned Benjamin Levi DeVore hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. To the best of my knowledge this thesis contains no material previously published by any other person except where proper acknowledgement has been made. This thesis contains no material which has been accepted as part of the requirements of any other academic degree or non-degree program, in English or in any other language. This is a true copy of the thesis, including final revisions. Date: 11 June 2020 Name: Benjamin Levi DeVore Signature: CEU eTD Collection ii Abstract While the dairy industry in the U.S. has maintained a strong influence on federal policymaking since at least the 19th century, their arsenal of lobbying tools has only grown over the past few decades. The industry’s unyielding strength is somewhat surprising given the multidimensional levels of criticism directed at the industry recently, including from economic, health, and environmental perspectives. This thesis aims to answer this apparent contradiction by examining three external aspects of lobbying influence—the revolving door phenomenon, political donations, and industry-funded nutritional studies—in addition to deep-seated conflicts of interest present within the USDA. Specific mechanisms for each of these factors has allowed the dairy industry to dominate in Washington, displayed by their advocate strength, financial superiority, and research prowess. -

Stories of the Prophets

Stories of the Prophets Written by Al-Imam ibn Kathir Translated by Muhammad Mustapha Geme’ah, Al-Azhar Stories of the Prophets Al-Imam ibn Kathir Contents 1. Prophet Adam 2. Prophet Idris (Enoch) 3. Prophet Nuh (Noah) 4. Prophet Hud 5. Prophet Salih 6. Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham) 7. Prophet Isma'il (Ishmael) 8. Prophet Ishaq (Isaac) 9. Prophet Yaqub (Jacob) 10. Prophet Lot (Lot) 11. Prophet Shuaib 12. Prophet Yusuf (Joseph) 13. Prophet Ayoub (Job) 14 . Prophet Dhul-Kifl 15. Prophet Yunus (Jonah) 16. Prophet Musa (Moses) & Harun (Aaron) 17. Prophet Hizqeel (Ezekiel) 18. Prophet Elyas (Elisha) 19. Prophet Shammil (Samuel) 20. Prophet Dawud (David) 21. Prophet Sulaiman (Soloman) 22. Prophet Shia (Isaiah) 23. Prophet Aramaya (Jeremiah) 24. Prophet Daniel 25. Prophet Uzair (Ezra) 26. Prophet Zakariyah (Zechariah) 27. Prophet Yahya (John) 28. Prophet Isa (Jesus) 29. Prophet Muhammad Prophet Adam Informing the Angels About Adam Allah the Almighty revealed: "Remember when your Lord said to the angels: 'Verily, I am going to place mankind generations after generations on earth.' They said: 'Will You place therein those who will make mischief therein and shed blood, while we glorify You with praises and thanks (exalted be You above all that they associate with You as partners) and sanctify You.' Allah said: 'I know that which you do not know.' Allah taught Adam all the names of everything, then He showed them to the angels and said: "Tell Me the names of these if you are truthful." They (angels) said: "Glory be to You, we have no knowledge except what You have taught us. -

TNT December 10 2020

Greater New Life Family Worship Center Thursday Night Teaching December 10th, 2020 2020 Theme: “Still Here” Thematic Text: 1 Corinthians 15:58 (KJV) Therefore, my beloved brethren, be ye stedfast, unmoveable, always abounding in the work of the Lord, forasmuch as ye know that your labour is not in vain in the Lord. T.N.T TEACHING SERIES: THE MIGHTY ACTS OF GOD Base Text: Psalm 150:1-6 (A PSALM OF PRAISE) (KJV) 150 Praise ye the Lord. Praise God in his sanctuary: praise him in the firmament of his power. 2 Praise him for his mighty acts: praise him according to his excellent greatness. 3 Praise him with the sound of the trumpet: praise him with the psaltery and harp. 4 Praise him with the timbrel and dance: praise him with stringed instruments and organs. 5 Praise him upon the loud cymbals: praise him upon the high sounding cymbals. 6 Let every thing that hath breath praise the Lord. Praise ye the Lord. 1 MIGHTY ACTS (According To: Christoph Barth OT Theology) 1. God Created Heaven and Earth 2. God Chose the Fathers of Israel 3. God Brought Israel Out of Egypt 4. God Led His People Through the Wilderness 5. God Revealed Himself at Sinai 6. God Granted Israel the Land of Caanan 7. God Raised Up Kings in Israel 8. God Chose Jerusalem 9. God Sent His Prophets 2 MIGHTY ACT #2 ‘GOD CHOSE THE FATHERS OF ISRAEL’ PART 4e: JACOB LAST LESSON: Dec 3, 2020 V. A Father’s Punishment Genesis 28 New American Standard Bible (NASB) 28 So Isaac called Jacob and blessed him and commanded him, [a]saying to him, “You shall not take a wife from the daughters of Canaan. -

Family of Abraham

Family of Abraham Terah ? Haran Nahor Sarai - - - - - ABRAM - - - - - Hagar Lot Milcah Bethuel Ishmael (1) ISAAC (2) Daughter 1 Daughter 2 Ishmaelites (12 tribes / Arabs) Laban Rebekah Moabites Ammonites JACOB (2) Esau (1) Leah Rachel Edomites (+Zilpah) (+Bilhah) ISRAELITES Key: blue = men; red = women; (12 tribes / Jews) dashes = spouses; arrows = children Terah: from Ur of the Chaldeans; has 3 sons; wife not named (Gen 11:26-32; cf. Luke 3:34). Haran: dies in Ur before his father dies; wife not named; son Lot, daughters Milcah & Iscah (11:27-28). Nahor: marries Milcah, daughter of his brother Haran (11:29); have 8 sons, incl. Bethuel (22:20-24). Abram: main character of Gen 12–25; recipient of God’s promises; name changed to ABRAHAM (17:5); sons Ishmael (by Hagar) and Isaac (by Sarah); after Sarah’s death, takes another wife, Keturah, who has 6 sons (25:1-4), including Midian, ancestor of the Midianites (37:28-36). Lot: son of Haran, thus nephew of Abram, who takes care of him (11:27–14:16; 18:17–19:29); wife and two daughters never named; widowed daughters sleep with their father and bear sons, who become ancestors of the Moabites and Ammonites (19:30-38). Sarai: Abram’s wife, thus Terah’s daughter-in-law (11:29-31); Abram also calls her his “sister,” which seems deceptive in one story (12:10-20); but in another story Abram insists she really is his half- sister (his father’s daughter by another wife; 20:1-18); originally childless, but in old age has a son, Isaac (16:1–21:7); name changed to SARAH (17:15); dies and is buried in Hebron (23:1-20). -

A BEST WESTERN MOTEL for CARLSBAD, NEW MEXICO Presented to W. Lawrence Garvin, Chairman DIVISION of ARCHITECTURE TEXAS TECH UNIV

A BEST WESTERN MOTEL FOR CARLSBAD, NEW MEXICO Presented to W. Lawrence Garvin, Chairman DIVISION OF ARCHITECTURE TEXAS TECH UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment Of The Requirements Of The Bachelor Of Architecture Degree by Ron Childress Decemher 11, 1981 Table Of Contents Background Page 1 Activity Analysis Page 18 Site Analysis Page 33 Space Summary Page 40 Detailed Space List Page 42 Systems Performance Page 60 Cost Analysis Page 71 Goals And Objectives Page ^(^ Case Studies Page 78 Q Z Q (D u < ID The idea for this project had its inception in 197? when I was fully involved in the motel and restaurant business in Carlsbad, New Mexico, The corporation I was involved with purchased five acres of land with the express intention of building a motel on the site. A feasibility study was imder- taken, and was completed in September, 1977- The company conducting the study determined that the site location and cost of the site was not excessive for a project of the scope we had planned. The problem was in the room rate structure. Historically Carlsbad has had low guest room rates relative to the industry as a whole, and the region in particular. The recommendation was to delay or postpone construction plans until testing the market with significantly higher rates. The motel operators in Carlsbad have since raised their rates considerably since 1977f and based on the feasibility study's figures, I believe the project is feasible now. This project is significant to me because of the feasi bility of the project now, because there is a good possibility that the project might actually be constructed from the design I generate in Thesis studio, or at least based on my design. -

Frank Lloyd Wright - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Frank Lloyd Wright - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Frank_... Frank Lloyd Wright From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Frank Lloyd Wright (born Frank Lincoln Wright, June 8, 1867 – April 9, Frank Lloyd Wright 1959) was an American architect, interior designer, writer and educator, who designed more than 1000 structures and completed 532 works. Wright believed in designing structures which were in harmony with humanity and its environment, a philosophy he called organic architecture. This philosophy was best exemplified by his design for Fallingwater (1935), which has been called "the best all-time work of American architecture".[1] Wright was a leader of the Prairie School movement of architecture and developed the concept of the Usonian home, his unique vision for urban planning in the United States. His work includes original and innovative examples of many different building types, including offices, churches, schools, Born Frank Lincoln Wright skyscrapers, hotels, and museums. Wright June 8, 1867 also designed many of the interior Richland Center, Wisconsin elements of his buildings, such as the furniture and stained glass. Wright Died April 9, 1959 (aged 91) authored 20 books and many articles and Phoenix, Arizona was a popular lecturer in the United Nationality American States and in Europe. His colorful Alma mater University of Wisconsin- personal life often made headlines, most Madison notably for the 1914 fire and murders at his Taliesin studio. Already well known Buildings Fallingwater during his lifetime, Wright was recognized Solomon R. Guggenheim in 1991 by the American Institute of Museum Architects as "the greatest American Johnson Wax Headquarters [1] architect of all time." Taliesin Taliesin West Robie House Contents Imperial Hotel, Tokyo Darwin D.