The Phrase Structure Component of Our Grammar of English Written By: Emma, Chloe, Jacob, Shawna, and Sam September 29, 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

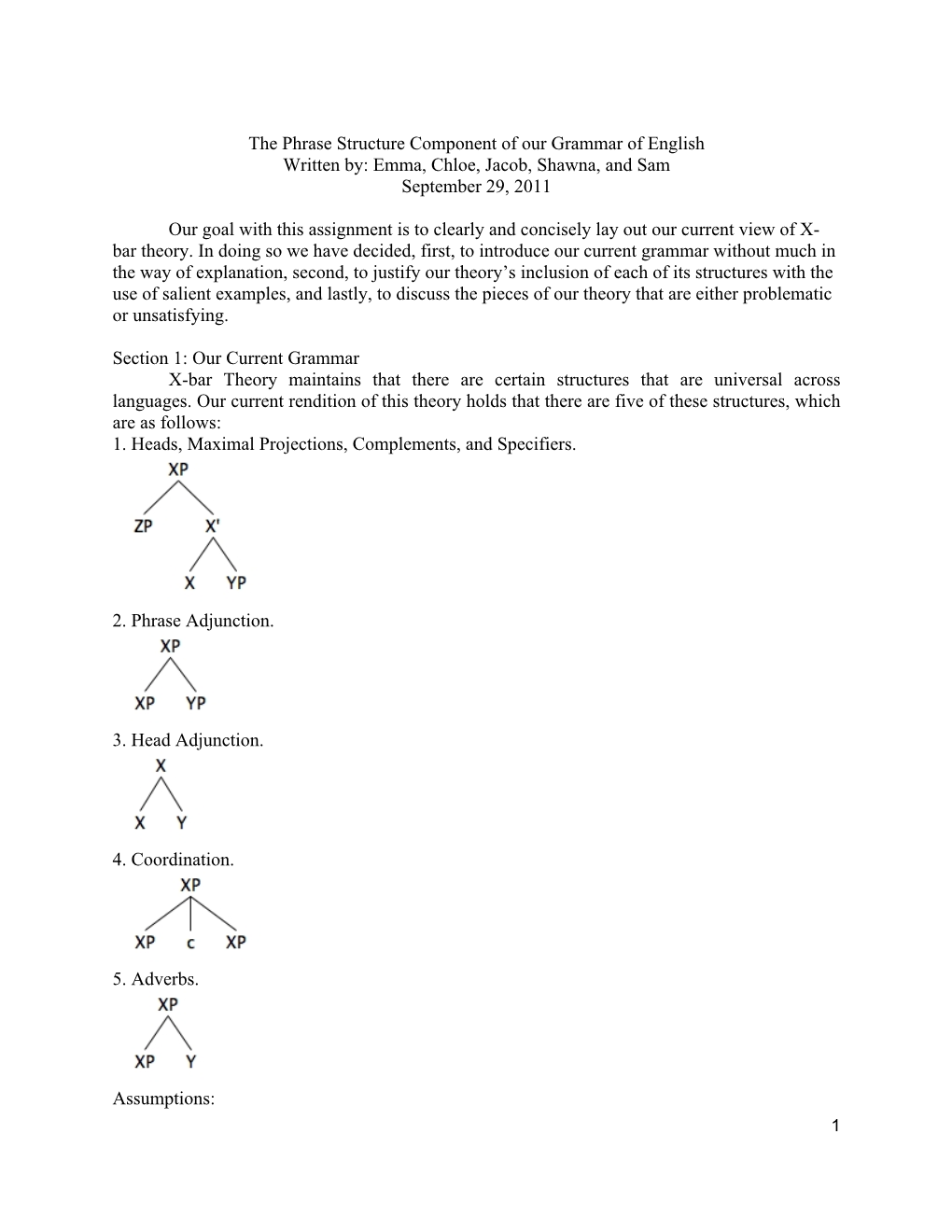

Recommended publications

-

Lisa Pearl LING200, Summer Session I, 2004 Syntax – Sentence Structure

Lisa Pearl LING200, Summer Session I, 2004 Syntax – Sentence Structure I. Syntax A. Gives us the ability to say something new with old words. Though you have seen all the words that I’m using in this sentence before, it’s likely you haven’t seen them put together in exactly this way before. But you’re perfectly capable of understanding the sentence, nonetheless. A. Structure: how to put words together. A. Grammatical structure: a way to put words together which is allowed in the language. a. I often paint my nails green or blue. a. *Often green my nails I blue paint or. II. Syntactic Categories A. How to tell which category a word belongs to: look at the type of meaning the word has, the type of affixes which can adjoin to the word, and the environments you find the word in. A. Meaning: tell lexical category from nonlexical category. a. lexical – meaning is fairly easy to paraphrase i. vampire ≈ “night time creature that drinks blood” i. dark ≈ “without much light” i. drink ≈ “ingest a liquid” a. nonlexical – meaning is much harder to pin down i. and ≈ ?? i. the ≈ ?? i. must ≈ ?? a. lexical categories: Noun, Verb, Adjective, Adverb, Preposition i. N: blood, truth, life, beauty (≈ entities, objects) i. V: bleed, tell, live, remain (≈ actions, sensations, states) i. A: gory, truthful, riveting, beautiful (≈ property/attribute of N) 1. gory scene 1. riveting tale i. Adv: sharply, truthfully, loudly, beautifully (≈ property/attribute of V) 1. speak sharply 1. dance beautifully i. P: to, from, inside, around, under (≈ indicates path or position w.r.t N) 1. -

The Internal Syntax of the Chimakonde Determiner Phrase

THE INTERNAL SYNTAX OF THE CHIMAKONDE DETERMINER PHRASE By DOMINICK MAKANJILA Dissertation presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Professor Marianna W. Visser April 2019 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION By submitting this dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: April 2019 Copyright © 2019 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ABSTRACT In the Government-and-Binding theory of generative syntax (cf. Chomsky, 1981), it was posited that a functional head D(eterminer) heads a noun phrase (NP). This view is referred to as a Determiner Phrase (DP) hypothesis (Abney, 1987). English articles are uncontroversially viewed as instantiations of D. Consequently, some scholars hold that a DP projects only in languages with articles (cf. Bruening, 2009). However, the universal view of the DP hypothesis, which this study also invokes, is that both languages with and without articles project a DP (cf. Veselovská, 2014). It is argued that articles (like those found in English) are not the only forms through which the functional category D can manifest. Different languages have different manifestations of the functional category D. The category D is viewed as the locus of (in)definiteness and (non-)specificity). -

A More Perfect Tree-Building Machine 1. Refining Our Phrase-Structure

Intro to Linguistics Syntax 2: A more perfect Tree-Building Machine 1. Refining our phrase-structure rules Rules we have so far (similar to the worksheet, compare with previous handout): a. S → NP VP b. NP → (D) AdjP* N PP* c. VP → (AdvP) V (NP) PP* d. PP → P NP e. AP --> (Deg) A f. AdvP → (Deg) Adv More about Noun Phrases Last week I drew trees for NPs that were different from those in the book for the destruction of the city • What is the difference between the two theories of NP? Which one corresponds to the rule (b)? • What does the left theory claim that the right theory does not claim? • Which is closer to reality? How did can we test it? On a related note: how many meanings does one have? 1) John saw a large pink plastic balloon, and I saw one, too. Let us improve our NP-rule: b. CP = Complementizer Phrase Sometimes we get a sentence inside another sentence: Tenors from Odessa know that sopranos from Boston sing songs of glory. We need to have a new rule to build a sentence that can serve as a complement of a verb, where C complementizer is “that” , “whether”, “if” or it could be silent (unpronounced). g. CP → C S We should also improve our rule (c) to be like the one below. c. VP → (AdvP) V (NP) PP* (CP) (says CP can co-occur with NP or PP) Practice: Can you draw all the trees in (2) using the amended rules? 2) a. Residents of Boston hear sopranos of renown at dusk. -

RELATIONAL NOUNS, PRONOUNS, and Resumptionw Relational Nouns, Such As Neighbour, Mother, and Rumour, Present a Challenge to Synt

Linguistics and Philosophy (2005) 28:375–446 Ó Springer 2005 DOI 10.1007/s10988-005-2656-7 ASH ASUDEH RELATIONAL NOUNS, PRONOUNS, AND RESUMPTIONw ABSTRACT. This paper presents a variable-free analysis of relational nouns in Glue Semantics, within a Lexical Functional Grammar (LFG) architecture. Rela- tional nouns and resumptive pronouns are bound using the usual binding mecha- nisms of LFG. Special attention is paid to the bound readings of relational nouns, how these interact with genitives and obliques, and their behaviour with respect to scope, crossover and reconstruction. I consider a puzzle that arises regarding rela- tional nouns and resumptive pronouns, given that relational nouns can have bound readings and resumptive pronouns are just a specific instance of bound pronouns. The puzzle is: why is it impossible for bound implicit arguments of relational nouns to be resumptive? The puzzle is highlighted by a well-known variety of variable-free semantics, where pronouns and relational noun phrases are identical both in category and (base) type. I show that the puzzle also arises for an established variable-based theory. I present an analysis of resumptive pronouns that crucially treats resumptives in terms of the resource logic linear logic that underlies Glue Semantics: a resumptive pronoun is a perfectly ordinary pronoun that constitutes a surplus resource; this surplus resource requires the presence of a resumptive-licensing resource consumer, a manager resource. Manager resources properly distinguish between resumptive pronouns and bound relational nouns based on differences between them at the level of semantic structure. The resumptive puzzle is thus solved. The paper closes by considering the solution in light of the hypothesis of direct compositionality. -

Linguistics 21N - Linguistic Diversity and Universals: the Principles of Language Structure

Linguistics 21N - Linguistic Diversity and Universals: The Principles of Language Structure Ben Newman March 1, 2018 1 What are we studying in this course? This course is about syntax, which is the subfield of linguistics that deals with how words and phrases can be combined to form correct larger forms (usually referred to as sentences). We’re not particularly interested in the structure of words (morphemes), sounds (phonetics), or writing systems, but instead on the rules underlying how words and phrases can be combined across different languages. These rules are what make up the formal grammar of a language. Formal grammar is similar to what you learn in middle and high school English classes, but is a lot more, well, formal. Instead of classifying words based on meaning or what they “do" in a sentence, formal grammars depend a lot more on where words are in the sentence. For example, in English class you might say an adjective is “a word that modifies a noun”, such as red in the phrase the red ball. A more formal definition of an adjective might be “a word that precedes a noun" or “the first word in an adjective phrase" where the adjective phrase is red ball. Describing a formal grammar involves writing down a lot of rules for a language. 2 I-Language and E-Language Before we get into the nitty-gritty grammar stuff, I want to take a look at two ways language has traditionally been described by linguists. One of these descriptions centers around the rules that a person has in his/her mind for constructing sentences. -

Language Structure: Phrases “Productivity” a Property of Language • Definition – Language Is an Open System

Language Structure: Phrases “Productivity” a property of Language • Definition – Language is an open system. We can produce potentially an infinite number of different messages by combining elements differently. • Example – Words into phrases. An Example of Productivity • Human language is a communication system that bears some similarities to other animal communication systems, but is also characterized by certain unique features. (24 words) • I think that human language is a communication system that bears some similarities to other animal communication systems, but is also characterized by certain unique features, which are fascinating in and of themselves. (33 words) • I have always thought, and I have spent many years verifying, that human language is a communication system that bears some similarities to other animal communication systems, but is also characterized by certain unique features, which are fascinating in and of themselves. (42 words) • Although mainstream some people might not agree with me, I have always thought… Creating Infinite Messages • Discrete elements – Words, Phrases • Selection – Ease, Meaning, Identity • Combination – Rules of organization Models of Word reCombination 1. Word chains (Markov model) Phrase-level meaning is derived from understanding each word as it is presented in the context of immediately adjacent words. 2. Hierarchical model There are long-distant dependencies between words in a phrase, and these inform the meaning of the entire phrase. Markov Model Rule: Select and concatenate (according to meaning and what types of words should occur next to each other). bites bites bites Man over over over jumps jumps jumps house house house Markov Model • Assumption −Only adjacent words are meaningfully (and lawfully) related. -

Antisymmetry Kayne, Richard (1995)

CAS LX 523 Syntax II (1) A Spring 2001 March 13, 2001 qp Paul Hagstrom Week 7: Antisymmetry BE 33 Kayne, Richard (1995). The antisymmetry of syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. CDFG 1111 Koopman, Hilda (2000). The spec-head configuration. In Koopman, H., The syntax of cdef specifiers and heads. London: Routledge. (2) A node α ASYMMETRICALLY C-COMMANDS β if α c-commands β and β does not The basic proposals: c-command α. X-bar structures (universally) have a strict order: Spec-head-complement. There is no distinction between adjuncts and specifiers. • B asymmetrically c-commands F and G. There can be only one specifier. • E asymmetrically c-commands C and D. • No other non-terminal nodes asymmetrically c-command any others. But wait!—What about SOV languages? What about multiple adjunction? Answer: We’ve been analyzing these things wrong. (3) d(X) is the image of a non-terminal node X. Now, we have lots of work to do, because lots of previous analyses relied on d(X) is the set of terminal nodes dominated by node X. the availability of “head-final” structures, or multiple adjunction. • d(C) is {c}. Why make our lives so difficult? Wasn’t our old system good enough? • d(B) is {c, d}. Actually, no. • d(F) is {e}. A number of things had to be stipulated in X-bar theory (which we will review); • d(E) is {e, f}. they can all be made to follow from one general principle. • d(A) is {c, d, e, f}. The availability of a head-parameter actually fails to predict the kinds of languages that actually exist. -

Antisymmetry and the Lefthand in Morphology*

CatWPL 7 071-087 13/6/00 12:26 Página 71 CatWPL 7, 1999 71-87 Antisymmetry And The Lefthand In Morphology* Frank Drijkoningen Utrecht Institute of Linguistics-OTS. Department of Foreign Languages Kromme Nieuwegracht 29. 3512 HD Utrecht. The Netherlands [email protected] Received: December 13th 1998 Accepted: March 17th 1999 Abstract As Kayne (1994) has shown, the theory of antisymmetry of syntax also provides an explanation of a structural property of morphological complexes, the Righthand Head Rule. In this paper we show that an antisymmetry approach to the Righthand Head Rule eventually is to be preferred on empirical grounds, because it describes and explains the properties of a set of hitherto puzz- ling morphological processes —known as discontinuous affixation, circumfixation or parasyn- thesis. In considering these and a number of more standard morphological structures, we argue that one difference bearing on the proper balance between morphology and syntax should be re-ins- talled (re- with respect to Kayne), a difference between the antisymmetry of the syntax of mor- phology and the antisymmetry of the syntax of syntax proper. Key words: antisymmetry, Righthand Head Rule, circumfixation, parasynthesis, prefixation, category-changing prefixation, discontinuities in morphology. Resum. L’antisimetria i el costat esquerre en morfologia Com Kayne (1994) mostra, la teoria de l’antisimetria en la sintaxi també ens dóna una explicació d’una propietat estructural de complexos morfològics, la Regla del Nucli a la Dreta. En aquest article mostrem que un tractament antisimètric de la Regla del Nucli a la Dreta es prefereix even- tualment en dominis empírics, perquè descriu i explica les propietats d’una sèrie de processos fins ara morfològics —coneguts com afixació discontínua, circumfixació o parasíntesi. -

Wh-Movement in Standard Arabic: an Optimality

Poznań Studies in Contemporary Linguistics 46(1), 2010, pp. 1–26 © School of English, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, Poland doi:10.2478/v10010-010-0001-y WH-MOVEMENT IN STANDARD ARABIC: AN OPTIMALITY-THEORETIC ACCOUNT MOUSA A. BTOOSH Al-Hussein Bin Talal University, Ma’an [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper is meant to delineate the syntax of wh-movement in Standard Arabic within the Opti- mality Theory framework. The scope of this study is limited to examine only simple, relativized and indirect verbal information questions. Further restrictions also have been placed on tense and negation in that only past tense affirmative questions are tackled here. Results show that Standard Arabic strictly adheres to the OP SPEC constraint in the matrix as well as the subordinate clauses. Findings also show that *Prep-Strand violation is intolerable in all types of information questions. Furthermore, the phonological manifestation of the com- plementizer is obligatory when the relative clause head is present or when the relative clause head is deleted and a resumptive pronoun is left behind. KEYWORDS : Wh-movement; constraints; questions; resumptive pronouns; relative clauses. 1. Introduction and review of literature Languages vary not only as to where they place wh-words or phrases, but also in the constraints governing the movement process, in general. In spite of the different kinds of movement that languages feature (topicalization, extraposition, wh-movement, heavy NP-shift, etc.), all of such syntactic phenomena do share a common property, the movement of a category from a place to another. Though its roots began long before, the unified theory of wh-movement came into being by the publication of Chomsky’s article On wh-movement in 1977. -

Syntax of Elliptical and Discontinuous Nominals

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Syntax of Elliptical and Discontinuous Nominals A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Linguistics by Dimitrios Ntelitheos 2004 1 The thesis of Dimitrios Ntelitheos is approved. _________________________________ Anoop Mahajan _________________________________ Timothy A. Stowell _________________________________ Hilda Koopman, Committee Chair University of California, Los Angeles 2004 2 στον Αλέξανδρο … για κείνον που ήρθε ανάµεσά µας να σφίξει τα δαχτυλά µας στην παλάµη … Μ. Αναγνωστάκης 3 CONTENTS 1 Introduction 1 2 Nominal Ellipsis and Discontinuity as Sister Operations 6 2.1 Nominal Ellipsis as NP-Topicalization 6 2.1.1 Ellipsis and Movement 6 2.1.2 On a Nominal Left Periphery 10 2.1.3 On the Existence of a Nominal FocusP 12 2.1.4 On the existence of a Nominal TopicP 18 2.2 Focus as a Licensing Mechanism for Nominal Ellipsis 25 2.2.1 Against a pro Analysis of Nominal Ellipsis 25 2.2.2 Focus Condition on Ellipsis 30 2.3 Topicalization and Focalization in Discontinuous DPs 33 2.4 Ellipsis and rich morphology 38 2.5 Fanselow & Ćavar (2002) 51 3 Common Properties Between Nominal Ellipsis and Discontinuous DPs 54 3.1 Same Type of Modifiers 54 3.2 Morphological Evidence 58 4 Some Problems 60 4.1 Restrictions on Discontinuity 60 4.2 Discontinuity without Nominal Ellipsis 64 5 Conclusion 69 References 70 4 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Syntax of Elliptical and Discontinuous Nominals by Dimitrios Ntelitheos Master of Arts in Linguistics University of California, Los Angeles, 2003 Professor Hilda Koopman, Chair This thesis proposes a new analysis of two superficially different phenomena – nominal ellipsis and discontinuous DPs. -

Processing English with a Generalized Phrase Structure Grammar

PROCESSING ENGLISH WITH A GENERALIZED PHRASE STRUCTURE GRAMMAR Jean Mark Gawron, Jonathan King, John Lamping, Egon Loebner, Eo Anne Paulson, Geoffrey K. Pullum, Ivan A. Sag, and Thomas Wasow Computer Research Center Hewlett Packard Company 1501 Page Mill Road Palo Alto, CA 94304 ABSTRACT can be achieved without detailed syntactic analysis. There is, of course, a massive This paper describes a natural language pragmatic component to human linguistic processing system implemented at Hewlett-Packard's interaction. But we hold that pragmatic inference Computer Research Center. The system's main makes use of a logically prior grammatical and components are: a Generalized Phrase Structure semantic analysis. This can be fruitfully modeled Grammar (GPSG); a top-down parser; a logic and exploited even in the complete absence of any transducer that outputs a first-order logical modeling of pragmatic inferencing capability. representation; and a "disambiguator" that uses However, this does not entail an incompatibility sortal information to convert "normal-form" between our work and research on modeling first-order logical expressions into the query discourse organization and conversational language for HIRE, a relational database hosted in interaction directly= Ultimately, a successful the SPHERE system. We argue that theoretical language understanding system wilt require both developments in GPSG syntax and in Montague kinds of research, combining the advantages of semantics have specific advantages to bring to this precise, grammar-driven analysis of utterance domain of computational linguistics. The syntax structure and pragmatic inferencing based on and semantics of the system are totally discourse structures and knowledge of the world. domain-independent, and thus, in principle, We stress, however, that our concerns at this highly portable. -

Possessive Nominal Expressions in GB: DP Vs. NP

Possessive Nominal Expressions in GB: DP vs. NP Daniel W. Bruhn December 8, 2006 1 Introduction 1.1 Background Since Steven Abney's 1987 MIT dissertation, The English Noun Phrase in Its Sentential Aspect, the so- called DP Hypothesis has gained acceptance in the eld of Government and Binding (GB) syntax. This hypothesis proposes that a nominal expression1 is headed by a determiner that takes a noun phrase as its complement. The preexisting NP Hypothesis, on the other hand, diagrams nominal expressions as headed by nouns, sometimes taking a determiner phrase as a specier.2 This basic dierence is illustrated in the following trees for the nominal expression the dog: NP DP DP N0 D0 D0 N0 D0 NP dog the D0 N0 the N0 dog The number of dierent types of nominal expressions that could serve as the basis for an NP vs. DP Hypothesis comparison is naturally quite large, and to address every one would be quite a feat for this squib. I have therefore chosen to concentrate on possessive nominal expressions because they exhibit a certain array of properties that pose challenges for both hypotheses, and will present these according to the following structure: Section 2.1 (Possessive) nominals posing no problem for either hypothesis Section 2.2 Problem nominals for the NP Hypothesis Section 2.3 How the DP Hypothesis accounts for the problem nominals of the NP Hypothesis Section 2.4 Problem nominals for the DP Hypothesis Section 2.5 How the NP Hypothesis accounts for the problem nominals of the DP Hypothesis By problem nominals, I mean those which expose some weakeness in the ability of either hypothesis to: 1.