Video Games in the Middle School Classroom Page 1 of 14

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Buy DVD PC Games : 6 Ribu/DVD Nama

www.GamePCmurah.tk How To Buy DVD PC Games : 6 ribu/DVD Nama. DVD Genre Type Daftar Game Baru di urutkan berdasarkan tanggal masuk daftar ke list ini Assassins Creed : Brotherhood 2 Action Setup Battle Los Angeles 1 FPS Setup Call of Cthulhu: Dark Corners of the Earth 1 Adventure Setup Call Of Duty American Rush 2 1 FPS Setup Call Of Duty Special Edition 1 FPS Setup Car and Bike Racing Compilation 1 Racing Simulation Setup Cars Mater-National Championship 1 Racing Simulation Setup Cars Toon: Mater's Tall Tales 1 Racing Simulation Setup Cars: Radiator Springs Adventure 1 Racing Simulation Setup Casebook Episode 1: Kidnapped 1 Adventure Setup Casebook Episode 3: Snake in the Grass 1 Adventure Setup Crysis: Maximum Edition 5 FPS Setup Dragon Age II: Signature Edition 2 RPG Setup Edna & Harvey: The Breakout 1 Adventure Setup Football Manager 2011 versi 11.3.0 1 Soccer Strategy Setup Heroes of Might and Magic IV with Complete Expansion 1 RPG Setup Hotel Giant 1 Simulation Setup Metal Slug Anthology 1 Adventure Setup Microsoft Flight Simulator 2004: A Century of Flight 1 Flight Simulation Setup Night at the Museum: Battle of the Smithsonian 1 Action Setup Naruto Ultimate Battles Collection 1 Compilation Setup Pac-Man World 3 1 Adventure Setup Patrician IV Rise of a Dynasty (Ekspansion) 1 Real Time Strategy Setup Ragnarok Offline: Canopus 1 RPG Setup Serious Sam HD The Second Encounter Fusion (Ekspansion) 1 FPS Setup Sexy Beach 3 1 Eroge Setup Sid Meier's Railroads! 1 Simulation Setup SiN Episode 1: Emergence 1 FPS Setup Slingo Quest 1 Puzzle -

Business Simulation Game Games List

Business Simulation Game Games List Aerobiz https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/aerobiz-2526874 https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/1830%3A-railroads-%26-robber-barons- 1830: Railroads & Robber Barons 4554313 Designer's World https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/designer%27s-world-16960041 SimRefinery https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/simrefinery-7517236 Caterpillar Construction Tycoon https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/caterpillar-construction-tycoon-5051940 Donald Trump's Real Estate Tycoon https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/donald-trump%27s-real-estate-tycoon-3713654 Mall Tycoon https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/mall-tycoon-3118448 Mad TV https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/mad-tv-1063640 Friends for Sale https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/friends-for-sale-5504235 Detroit https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/detroit-1642809 Star Trader https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/star-trader-56071656 Micropolis https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/micropolis-2719130 Top Management https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/top-management-1591807 Burger Burger https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/burger-burger-4998533 Casino Tycoon https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/casino-tycoon-5048889 Business Games https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/business-games-5001725 Wildlife Park 2 https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/wildlife-park-2-2071485 Restaurant Empire https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/restaurant-empire-2270100 Business Tycoon Online https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/business-tycoon-online-5001816 Powerhouse https://www.listvote.com/lists/games/powerhouse-56274929 -

Games of Empire Electronic Mediations Katherine Hayles, Mark Poster, and Samuel Weber, Series Editors

Games of Empire Electronic Mediations Katherine Hayles, Mark Poster, and Samuel Weber, Series Editors 29 Games of Empire: Global Capitalism and Video Games Nick Dyer- Witheford and Greig de Peuter 28 Tactical Media Rita Raley 27 Reticulations: Jean-Luc Nancy and the Networks of the Political Philip Armstrong 26 Digital Baroque: New Media Art and Cinematic Folds Timothy Murray 25 Ex- foliations: Reading Machines and the Upgrade Path Terry Harpold 24 Digitize This Book! The Politics of New Media, or Why We Need Open Access Now Gary Hall 23 Digitizing Race: Visual Cultures of the Internet Lisa Nakamura 22 Small Tech: The Culture of Digital Tools Byron Hawk, David M. Rieder, and Ollie Oviedo, Editors 21 The Exploit: A Theory of Networks Alexander R. Galloway and Eugene Thacker 20 Database Aesthetics: Art in the Age of Information Overfl ow Victoria Vesna, Editor 19 Cyberspaces of Everyday Life Mark Nunes 18 Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture Alexander R. Galloway 17 Avatars of Story Marie-Laure Ryan 16 Wireless Writing in the Age of Marconi Timothy C. Campbell 15 Electronic Monuments Gregory L. Ulmer 14 Lara Croft: Cyber Heroine Astrid Deuber- Mankowsky 13 The Souls of Cyberfolk: Posthumanism as Vernacular Theory Thomas Foster 12 Déjà Vu: Aberrations of Cultural Memory Peter Krapp 11 Biomedia Eugene Thacker 10 Avatar Bodies: A Tantra for Posthumanism Ann Weinstone 9 Connected, or What It Means to Live in the Network Society Steven Shaviro 8 Cognitive Fictions Joseph Tabbi 7 Cybering Democracy: Public Space and the Internet Diana Saco 6 Writings Vilém Flusser 5 Bodies in Technology Don Ihde 4 Cyberculture Pierre Lévy 3 What’s the Matter with the Internet? Mark Poster 2 High Techne¯: Art and Technology from the Machine Aesthetic to the Posthuman R. -

Column1column2 PC0001 PCA PC0002 PCA PC0003 PCA

KODE STK Untuk mencari judul tekan CTRL + F , kemudian ketik judul pada tab FIND WHAT Column1Column2 PC0001 PCA PC0002 PCA PC0003 PCA PC0004 PCT PC0005 PCA PC0006 PCA PC0007 PCT PC0008 PCT PC0009 PCA PC0010 PCT PC0011 PCA PC0012 PCA PC0013 PCA PC0014 PCT PC0015 PCA PC0016 PCA PC0017 PCT PC0018 PCT PC0019 PCT PC0020 PCA PC0021 PCT PC0022 PCT PC0023 PCT PC0024 PCT PC1562 PCT PC0025 PCT PC0026 PCA PC0027 PCA PC0028 PCT PC0029 PCA PC0030 PCT PC0031 PCT PC0032 PCA PC0033 PCT PC0034 PCA PC0035 PCA PC0036 PCA PC0037 PCA PC1554 PCT PC1553 PCT PC0038 PCA PC0039 PCA PC0040 PCT PC0041 PCA PC0042 PCA PC0043 PCA PC0044 PCT PC0045 PCT PC0046 PCT PC0047 PCT PC0048 PCA PC0049 PCT PC0050 PCT PC0051 PCT PC0052 PCA PC0053 PCA PC0054 PCT PC0055 PCA PC0056 PCT PC0057 PCT PC0058 PCT PC0059 PCA PC0060 PCT PC0061 PCA PC0062 PCT PC0063 PCA PC0064 PCT PC0065 PCA PC0066 PCA PC0067 PCT PC0068 PCT PC0069 PCA PC0070 PCA PC0071 PCT PC0072 PCT PC0073 PCT PC0074 PCT PC0075 PCA PC0076 PCA PC0077 PCT PC0078 PCT PC0079 PCA PC0080 PCA PC0081 PCA PC0082 PCA PC0083 PCT PC0084 PCT PC0085 PCA PC0086 PCA PC0087 PCA PC0088 PCT PC0089 PCA PC0090 PCA PC0091 PCT PC0092 PCA PC0093 PCT PC0094 PCA PC0095 PCT PC0096 PCA PC0097 PCT PC1602 PCT PC0098 PCA PC0099 PCA PC0100 PCA PC0101 PCT PC0102 PCT PC0103 PCA PC0104 PCT PC0105 PCT PC0106 PCA PC0107 PCT PC0111 PCA PC0108 PCT PC0109 PCT PC0110 PCT PC0112 PCA PC0113 PCA PC0114 PCA PC0115 PCA PC0116 PCT PC0117 PCT PC0118 PCA PC0119 PCA PC0120 PCA PC0121 PCA PC0122 PCA PC0123 PCA PC1581 PCT PC0124 PCA PC0125 PCT PC0126 PCT PC0127 PCA PC0128 -

Technogamespc.Blogspot.Com 0838-225-599-59 (SMS) [email protected] (Email ) M.Kaskus.Co.Id/Thread/14826761 (Lapak) 25-029-34F (BB PIN )

Techno PC Games Technogamespc.Blogspot.Com 0838-225-599-59 (SMS) [email protected] (email ) m.kaskus.co.id/thread/14826761 (Lapak) 25-029-34F (BB PIN ) JUDUL GAME GENRE 7554 FPS 007 Legends action 1000 mini games vol.3 Collection 101 Dolphin Pets simulation 101st Airborne in Normandy strategy 110 Reflexive Arcade Games collection 132 NDS Game Collection collection 144 Mega Dash Collection Collection 150 Gamehouse Games collection 18 Wheels of Steel - Across America Driving 18 Wheels of Steel - American Long Haul Driving 18 Wheels of Steel - Convoy Driving 18 Wheels of Steel - Extreme Trucker Driving 18 Wheels of Steel - Extreme Trucker 2 racing 18 Wheels of Steel - Haulin Driving 18 Wheels of Steel - Pedal to the Metal Driving 18 Wheels of Steel Collection Driving 1953 KGB Unleashed FPS 2105 Nintendo NES all time collection 25 to Life action 327 Neo Geo 2011 collection 369 Sega Master System Collection collection 38 Classic Pinball Games Collection Arcade 3D Custom Girl adult 3D Sx Villa 2.99 adult 3D Ultra Cool Pool sport 3SwitcheD puzzle 46 Nintendo 64 collection 51 PopCap Games 2011 collection 534 MAME Games Collection collection 6666 Retro Legends Rom Packs (Sega, Snes, Nintendo 64 dll.) collection 7 Sins adult 7.62 High Calibre Strategy 772 Atari 2600 Games Collection collection 790 SNES Games 2011 collection 84 BigFish Games collection 948 Sega Mega Drive (Sega Genesis) Complete collection 99 Gameboy Advance Collection collection 9th Company Strategy Techno PC Games A Farewell To Dragons RPG A Game of Thrones Genesis strategy -

This Checklist Is Generated Using RF Generation's Database This Checklist Is Updated Daily, and It's Completeness Is Dependent on the Completeness of the Database

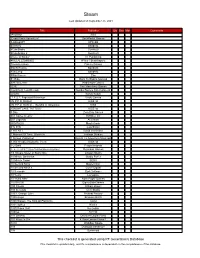

Steam Last Updated on September 25, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments !AnyWay! SGS !Dead Pixels Adventure! DackPostal Games !LABrpgUP! UPandQ #Archery Bandello #CuteSnake Sunrise9 #CuteSnake 2 Sunrise9 #Have A Sticker VT Publishing #KILLALLZOMBIES 8Floor / Beatshapers #monstercakes Paleno Games #SelfieTennis Bandello #SkiJump Bandello #WarGames Eko $1 Ride Back To Basics Gaming √Letter Kadokawa Games .EXE Two Man Army Games .hack//G.U. Last Recode Bandai Namco Entertainment .projekt Kyrylo Kuzyk .T.E.S.T: Expected Behaviour Veslo Games //N.P.P.D. RUSH// KISS ltd //N.P.P.D. RUSH// - The Milk of Ultraviolet KISS //SNOWFLAKE TATTOO// KISS ltd 0 Day Zero Day Games 001 Game Creator SoftWeir Inc 007 Legends Activision 0RBITALIS Mastertronic 0°N 0°W Colorfiction 1 HIT KILL David Vecchione 1 Moment Of Time: Silentville Jetdogs Studios 1 Screen Platformer Return To Adventure Mountain 1,000 Heads Among the Trees KISS ltd 1-2-Swift Pitaya Network 1... 2... 3... KICK IT! (Drop That Beat Like an Ugly Baby) Dejobaan Games 1/4 Square Meter of Starry Sky Lingtan Studio 10 Minute Barbarian Studio Puffer 10 Minute Tower SEGA 10 Second Ninja Mastertronic 10 Second Ninja X Curve Digital 10 Seconds Zynk Software 10 Years Lionsgate 10 Years After Rock Paper Games 10,000,000 EightyEightGames 100 Chests William Brown 100 Seconds Cien Studio 100% Orange Juice Fruitbat Factory 1000 Amps Brandon Brizzi 1000 Stages: The King Of Platforms ltaoist 1001 Spikes Nicalis 100ft Robot Golf No Goblin 100nya .M.Y.W. 101 Secrets Devolver Digital Films 101 Ways to Die 4 Door Lemon Vision 1 1010 WalkBoy Studio 103 Dystopia Interactive 10k Dynamoid This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

Requirements for Developing a Simulation Game for Maintenance Planner Training

Requirements for Developing a Simulation Game for Maintenance Planner Training THESIS BY EDWIN KAREMA This thesis is presented for the degree of Master of Engineering Science of the University of Western Australia School of Mechanical Engineering Engineering and Asset Management 2010 Requirements for Developing a Simulation Abstracts Game for Maintenance Planner Training Abstracts Today increasing market competitiveness has forced manufacturers and primary industries to compete on price and reliability. At the same time, there are greater complexities and risks associated with the purchasing, installing, and maintaining assets. These are some of the factors, which have lead to an increase in industry practitioners’ and academics’ interest in the study of asset management. Asset management itself is defined by Asset Management Council as “the life cycle management of physical assets to achieve the stated output of enterprise”. One of the key roles in the in-service phase of the life cycle is the maintenance planner. The planner input is vital in selecting and deploying the right maintenance tasks and sequences to ensure an asset's function is delivered at the optimal cost. One way to increase the effectiveness of the maintenance planning process is to improve the competency level of the maintenance planner. However, improving training and qualification systems is not straightforward. The lack of agreement on the maintenance planner tasks is one of the reasons why it is difficult to find a specific course for planners. Developing an effective training package for maintenance planners needs to consider planner competencies, cost, infrastructure, time flexibility and the content of the training itself. This could be achieved by developing a better understanding of maintenance planner role. -

Restaurant Empire 1 Game

Restaurant Empire 1 Game 1 / 6 Restaurant Empire 1 Game 2 / 6 3 / 6 Save time and money, compare CD Key Stores. Activate the Restaurant Empire 2 CD Key on your Steam client to download the game and play in multiplayer. Web ... 1. restaurant empire game 2. restaurant empire game play online 3. restaurant empire game mac 1. RESTAURANT EMPIRE (I). Total Games. Grupo F9*. CARACTERÍSTICAS DEL JUEGO. • TIPOLOGIA DEL JUEGO. RESTAURANT EMPIRE es un videojuego .... Restaurant Empire - PC - Video Game - VERY GOOD. SPONSORED ... RESTAURANT-EMPIRE-PC-Game-2003 thumbnail 1 ... 1 product rating | Write a review.. The sequel to the widely popular Restaurant Empire game takes you further into the depths and delights of the culinary universe than ever before. Take part in ... restaurant empire game restaurant empire game, restaurant empire game download, restaurant empire game play online, restaurant empire gameplay, restaurant empire game mac, my restaurant empire game, games like restaurant empire, restaurant empire 2 pc game download, restaurant empire 2 ocean of games, restaurant empire online free game, restaurant empire similar games, restaurant empire 2 gameplay, restaurant empire pc game, restaurant empire igg games Privacy Drive 3.16.5 Build 1427 Crack Restaurant Empire. Обзоры, описания, ссылки на скачивание, скриншоты, видеоролики.. Restaurant Empire is one of the best business simulation games developed till ... Empire Review: The Best Business Simulation Game of All Time – Page 1 of 2.. Restaurant Empire (PC): Amazon.co.uk: PC & Video Games. ... Turn on 1-Click ordering ... Set up restaurant themes such as music and seafood. 37 unique ... Secret Files 2: Puritas Cordis v1.1.1 Apk 4 / 6 EasyBilling Business Software v4.2.1-b489 With Crack restaurant empire game play online 10 bu c t o hi u ng ch song am The campaign mode features a remade version of the campaign in Restaurant Empire 1.