WH-1988-Dec-P28-29-Eng.Pdf (2.423Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MARCIA STEPHENSON Curriculum Vitae

1 MARCIA STEPHENSON Curriculum Vitae School of Languages and Cultures 164 Creighton Rd Stanley Coulter Hall West Lafayette, IN 47906 640 Oval Drive Phone: (765) 497-0051 Purdue University West Lafayette, IN 47907 E-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION: 1989 Ph.D., Hispanic Literature. Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana. 1981 M.A., Hispanic Literature. Indiana University. 1978 B.A., College of Wooster, Wooster, Ohio Major: Latin American Studies FIELDS OF Contemporary Latin American literary and cultural studies SPECIALIZATION: Andean cultural studies Feminist theory History of Science EMPLOYMENT: Purdue University Associate Professor of Spanish, 1997-present Assistant Professor of Spanish, 1991-1997 Grinnell College Assistant Professor of Spanish, 1989-1991 Instructor of Spanish, 1987-1989 Indiana University Preceptor (Course Coordinator), 1985-1987 Associate Instructor of Spanish, 1979-1987 Research Assistant, Office of Chicano-Riqueño Studies, 1980-1984 HONORS AND AWARDS: 2019 Aspire Research Enhancement Grant 2016 Aspire Research Enhancement Grant 2015-16 Purdue Research Foundation Grant 2015 CLA Outstanding Graduate Faculty Mentor Award 2015 2014-15 International Travel Grant 2014 NEH Research Grant 2014-15 Purdue Research Foundation Grant 2013-14 Purdue Research Foundation Grant 2013 Center for Humanistic Study, Fall semester, Purdue University 2013 Enhancing Research in the Humanities and Arts Grant, Purdue University 2012-13 Purdue Research Foundation Grant 2010-11 Purdue Research Foundation Grant 2008-09 Purdue Research Foundation Grant 2008 Center for Humanistic Study, Fall semester 2008 PRF International Travel Grant for travel to AHILA conference 2006-07 Purdue Research Foundation Grant Stephenson--2 2004-05 Purdue University Faculty Study in a Second Discipline 2003 Summer Library Research Fellowship in Latin American Studies, Cornell University. -

Treating Malaria

A Publication by The American Society for the Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics Pharmacologist Vol. 60 • Number 1 • March 2018 Treating Malaria – From Gin & Tonic to Chinese Herbs Inside: 2018 Election Results 2018 Award Winners ASPET Annual Meeting Program The Pharmacologist is published and distributed by the American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. THE PHARMACOLOGIST PRODUCTION TEAM Rich Dodenhoff Catherine L. Fry, PhD Dana Kauffman Contents Tyler Lamb Judith A. Siuciak, PhD Suzie Thompson Message from the President 1 COUNCIL President John D. Schuetz, PhD 3 2018 Election Results President-Elect Edward T. Morgan, PhD Past President 2018 Award Winners David R. Sibley, PhD 4 Secretary/Treasurer John J. Tesmer, PhD ASPET Annual Meeting Program Secretary/Treasurer-Elect 9 Margaret E. Gnegy, PhD Past Secretary/Treasurer Charles P. France, PhD 24 Feature Story: Treating Malaria Councilors – from Gin & Tonic to Chinese Herbs Wayne L. Backes, PhD Carol L. Beck, PharmD, PhD Alan V. Smrcka, PhD Meeting News Chair, Board of Publications Trustees 35 Mary E. Vore, PhD Chair, Program Committee Michael W. Wood, PhD Science Policy News FASEB Board Representative 41 Brian M. Cox, PhD Executive Officer 45 Education News Judith A. Siuciak, PhD The Pharmacologist (ISSN 0031-7004) Journals News is published quarterly in March, June, 49 September, and December by the American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 9650 52 Membership News Rockville Pike, Suite E220, Bethesda, Obituary: Darrell Abernethy MD 20814-3995. Annual subscription rates: $25.00 for ASPET members; $50.00 for U.S. nonmembers and institutions; $75.00 for nonmembers 57 Members in the News and institutions outside the U.S. -

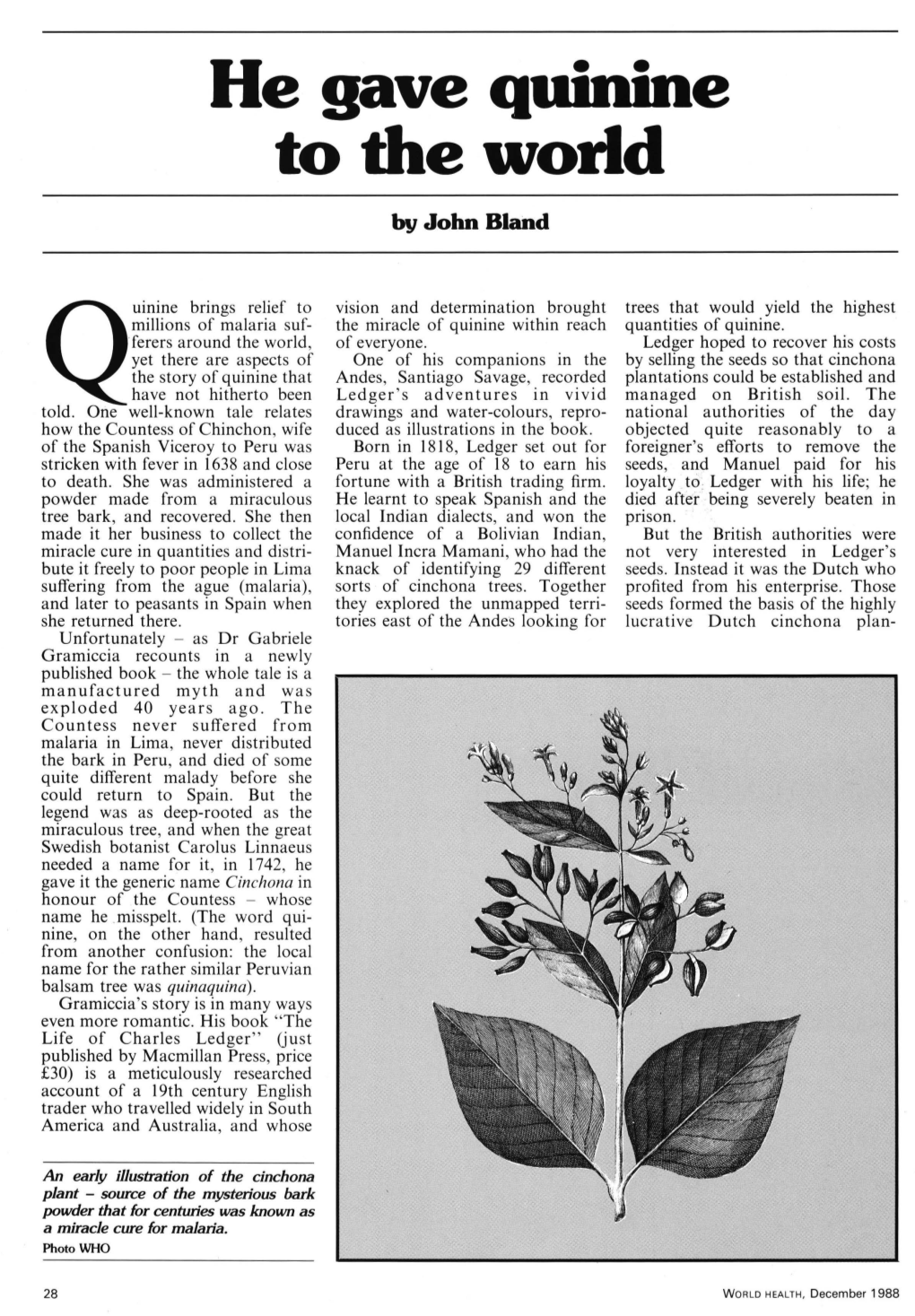

Book Reviews Appropriate Name of Money, Who Subsequently

Book Reviews (1938), 'Psychological medicine' (in 60,000 words for Prince's Textbook ofmedicine, 1941) and Health as a social concept (1953), he provided a clear, spare contrast to what Shepherd has called the "pleonastic obesity of most psychiatric textbooks". Many modern historians might blanch at his versions of philological history, but to Lewis history was of the essence. "Of the value of such studies it is unnecessary to speak." One hopes that the full story will now engage Professor Shepherd, soon to be free of institutional duties. This hors-d'oeuvre needs a main course. T. H. Turner Hackney Hospital, London GABRIELE GRAMICCIA, The life of Charles Ledger (1818-1905): alpacas and quinine, Basingstoke and London, Macmillan Press, 1988, 8vo, pp. xiv, 222, illus., £30.00. It was not until the very end of his career that Professor Gramiccia, a leading WHO malariologist now living in retirement in his native Italy, first happened to read about Charles Ledger in a popular periodical. He was so struck by the near-total oblivion into which the achievements of this adventurous predecessor had been allowed to fall that he was moved to embark on a full-scale biography, a task which he has pursued with impressive thoroughness in a range of countries around the world. Ledger left London for Peru on his eighteenth birthday to join a British merchant house specializing in two of that country's staples, alpaca wool and cinchona bark. After two years he was sent to run a branch in the southern port of Tacna, where he presently set up on his own account and married the daughter of a local official. -

Cinchona Or the Peruvian Bark

HISTORY PLANTS AGAINST MALARIA PART 1: CINCHONA OR THE PERUVIAN BARK M.R. Lee, Emeritus Professor of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, University of Edinburgh One of the most compelling sagas in the history of were prepared to use their knowledge of the bark to aid medicine and therapeutics is the emergence of the their struggles for power within the Church! Peruvian bark (Cinchona) and also of the pharma- cologically active substance derived from it, quinine. Its An important ecclesiastical figure, Cardinal de Lugo, now discovery involved exploration, exploitation and secrecy, emerges to take the initiative in the history of Cinchona and it came, in the nineteenth century, to reflect the (Figure 1). De Lugo was born in Madrid in 1585 but struggles of the major European powers for domination, spent his early years in Seville where he later became a territory and profit. This short history shows how the Jesuit priest.4 In 1621 he was transferred to the Collegium use of Cinchona enabled the exploration of dangerous Romanum in Rome, then the leading educational malarial areas and in this way facilitated imperial institution of the Jesuits. He taught there with distinction expansion by the Western powers. from his arrival until 1643. Initially de Lugo probably obtained the Peruvian bark from Father Tafur S.J. and, impressed by his preliminary trials of its efficacy, he THE PERUVIAN; JESUIT’S OR CARDINAL’S BARK purchased large amounts of it at his own expense. Many physicians are familiar with the story of the Countess Sturmius, a contemporary, reported that de Lugo ‘gave it of Chinchón, wife of the Viceroy of Peru; it was claimed gratis to the fevered poor, on condition only, that they by Bado that she was cured of a certain ague by did not sell it and that they presented a physician’s Cinchona bark sometime in the late 1620s or early statement about the illness’. -

The Dreadful Bight of Benin

The dreadful Bight of Benin Beware of the Bight of Benin Few came out though many went in Malaria • WHO estimate: 2-300 million deaths in 20th century = annual 3 million Agriculture, irrigation, settlements, higher population density, like the Fertile crescent.. Female mosquitoes with human blood preference Roman fever, King of fevers( Vedas), Alexander the Great ( 323 B.C. in Mesopotamia ), Hippocrates ( 460-377 B.C. ) Marsh fever, tertian, quatrian, recurrent fever The parazite and mala-aria • The protozoan parazite - Alfons Laveran 1880 • The vector: ANOPHELES - Ronald Mosquito Ross 1900 • 4 types of plasmodia • Rossi 1900 P. vivax tertian ( benign ) P.ovale P. malariae ( quartan ) - may stay in host for decades>infect mosquito> P. falciparum ( malignant subtertian, tropical malaria ) relatively new, Mediterranian region the distant relative of bird malaria, The name of the medicine, the bark of Loxa, the Legend quina, ghina, guina = the bark ( quechua-inka ) • Bado, Genoa 1653 • The miraculous recovery of Countess Chinchon wife if the Viceroy in Peru • Linne : Cinchona officinalis 1742 ( La Condamine ) The names of the bark • From Loxa Protectorate> The Loxa bark • Peruvian bark • Jesuit’s Bark • Cardinals Bark as champion for the use of the bark was Cardinal de Lugo as Director of Hospital Santo Spirito. • Bark tested by the Pope’s physician Fonseca. It appeared in 1651 in Schedula Romana as „ Corticus Peruvianus „ The meaning of the quinine/bark Agustino Salumbrino 1630 • Different meaning of the bark in the Americas and for Europeans? • San Pablo Hospital/Lima- Salumbrino • Analogue symptoms: shaking, shivering from cold and in thefever attack of malaria • 1492 and Genetic Polymorphism> P. -

War in Developing Drugs

Sourav Sarkar et al. / International Journal of Pharma Sciences and Research (IJPSR) War In Developing Drugs: A Case Study In Connection Sourav Sarkar1* & Anubhab Acharya2 1Department of Chemistry, Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur, India 721302 2Department of Chemistry, Ramakrishna Mission Residential College (Autonomous) Narendrapur, West Bengal, India 700103 *Email: [email protected] Contact: +919476245800 Abstract Truly someone said that “Necessity is the mother of invention”. Scientific evolution always comes with sociological need and temporary crisis in our daily life. The invention of fire, wheel for transportation, paper for documentation, each and every scientific invention is associated with some sociological need. Even these words are very true for discovery of medicines. It was until the starting of twentieth century i.e. the world war, which caused proper things and brought sufficient human attention towards the need of developing new medicines (Drugs) and medicinal techniques. In this article we shall try to reveal the very history with a strong emphasis on the chronological sequence. Keywords: Tropical disease, War, Pharmaceutical revolution, Malaria, Tuberculosis, Fungal infection, Viral infection, Cancer, Anesthetic and analgesic agent, Vaccine. Introduction The Old Days: From the very beginning of human evolution the philosophy regarding ‘Disease, Medicine and Cure’ was same. Something which could cure an ailment was considered to be a medicine. But the problem was those so called medicines were not well characterized, their side effects were not well studied; even the dosage were not standardized. In the cases of a few diseases the treatments were not known because of not having proper investigation on the field. -

Perspectives DOI 10.1007/S12038-013-9316-9

Perspectives DOI 10.1007/s12038-013-9316-9 Natural history in India during the 18th and 19th centuries RAJESH KOCHHAR Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, Mohali 140 306, Punjab (Email, [email protected]) 1. Introduction courier. We shall focus on India-based Europeans who built a scientific reputation for themselves; there were of course European access to India was multi-dimensional: The others who merely served as suppliers. merchant-rulers were keen to identify commodities that could be profitably exported to Europe, cultivate commercial plants in India that grew outside their possessions, and find 2. Tranquebar and Madras (1768–1793) substitutes for drugs and simples that were obtained from the Americas. The ever-increasing scientific community in As in geography, the earliest centre for botanical and zoo- Europe was excited about the opportunities that the vast logical research was South India. Europe-dictated scientific landmass of India offered in natural history studies. On their botany was begun in India by a direct pupil of Linnaeus not part, the Christianity enthusiasts in Europe viewed European in the British possessions but in the tiny Danish enclave of rule in India as a godsend for propagating the Gospel in the Tranquebar, which though of little significance as far as East. These seemingly diverse interests converged at various commerce or geo-politics was concerned, came to play an levels. Christian missionaries as a body were the first edu- extraordinary role in the cultural and scientific history of cated Europeans in India. As in philology, they were pio- India. neers in natural history also. -

Malarial Subjects: Empire, Medicine and Nonhumans in British India, 1820

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. Wellcome Library, on 09 Nov 2017 at 11:46:23, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/00BEE3F5FAD80653C99B6674E2685D4D Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. Wellcome Library, on 09 Nov 2017 at 11:46:23, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/00BEE3F5FAD80653C99B6674E2685D4D Malarial Subjects Malaria was considered one of the most widespread disease-causing entities in the nineteenth century. It was associated with a variety of frailties far beyond fevers, ranging from idiocy to impotence. And yet, it was not a self-contained category. The reconsolidation of malaria as a diagnostic category during this period happened within a wider context in which cinchona plants and their most valuable extract, quinine, were reinforced as objects of natural knowledge and social control. In India, the exigencies and apparatuses of British imperial rule occasioned the close interactions between these histories. In the process, British impe- rial rule became entangled with a network of nonhumans that included, apart from cinchona plants and the drug quinine, a range of objects described as malarial, as well as mosquitoes. Malarial Subjects explores this history of the co-constitution of a cure and disease, of British colo- nial rule and nonhumans, and of science, medicine and empire. This title is also available as Open Access. rohan deb roy is Lecturer in South Asian History at the University of Reading. He received his PhD from University College London, and has held postdoctoral fellowships at the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences Calcutta, at the University of Cambridge, and at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin. -

Reinventing Mecca

FFrroomm tthhee AAnnddeess ttoo tthhee OOuuttbbaacckk:: AAcccclliimmaattiissiinngg AAllppaaccaass iinn tthhee BBrriittiisshh EEmmppiirree HHeelleenn CCoowwiiee University of York April 2016 Copyright © Helen Cowie, 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. Requests for permission to reproduce any part of this Working Paper should be sent to: The Editor, Commodities of Empire Working Papers, Institute of Latin American Studies, University of London, Senate House, Malet St., London WC1H 0XG Commodities of Empire Working Paper No.24 ISSN: 1756-0098 From the Andes to the Outback: Acclimatising Alpacas in the British Empire Helen Cowie (University of York) In 1811 the first alpaca to be exhibited in Britain was put on show at Edward Cross’s menagerie in London. The animal, which had been a pet in its native Lima, was “remarkably tame” and had “perforations in its ears in which ornamental rings had been placed”. It soon proved a great favourite with the British public, who admired its “graceful attitudes, gentle disposition and playful manners” and expressed particular interest in its wool, which was thick, glossy and “about eighteen inches long”. One admirer, Lady Liverpool, was: so much…delighted with [the alpaca’s] beauty, the softness and brilliancy of its coat and its animated and beaming features that she kissed it as if it had been a child, and had it turned loose on her lawn, in order that she might witness its movements free from restraint’.1 The arrival of the alpaca in the aftermath of Spanish American independence sparked interest in Britain in the possibility of naturalising the species and using its wool for textile manufacture. -

(Carapichea Ipecacuanha (Brot.) L. Andersson): Plants for Medicinal Use from the 16Th Century to the Present

journal of herbal medicine 2 (2012) 103–112 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/hermed Review Use and importance of quina (Cinchona spp.) and ipeca (Carapichea ipecacuanha (Brot.) L. Andersson): Plants for medicinal use from the 16th century to the present Washington Soares Ferreira Júnior ∗, Margarita Paloma Cruz, Lucilene Lima dos Santos, Maria Franco Trindade Medeiros Laboratory of Applied Ethnobotany, Department of Biology, Federal Rural University of Pernambuco, Av. Dom Manoel de Medeiros, s/n, Dois Irmãos, CEP: 52171-900, Recife, PE, Brazil article info abstract Article history: Observations in prescriptions of the monasteries’ apothecaries of São Bento from Rio de Received 1 February 2012 Janeiro (Rio de Janeiro) and Olinda (Pernambuco) dating from the nineteenth century, Received in revised form prescribed quina (Cinchona spp., Rubiaceae) and ipeca (Carapichea ipecacuanha [Brot.] L. Ander- 30 May 2012 sson, Rubiaceae) for antidiarrheal/febrifuge and emetic/expectorant uses. In addition to Accepted 30 July 2012 these observations, pharmacological and anthropological literature indicate a great impor- Available online 4 October 2012 tance of using these plants for treating human diseases since ancient times. From this information, the present work conducts a literature review to investigate the history of dis- Keywords: covery and use of these species, recovering information about past and current uses of quina Historical ethnobotany and ipeca, seeking also to record possible changes -

Col. JW Gifford

NOVEMBER 29, 1930] NATURE 851 By following a devious route the explorers arrived so that they might recuperate ere they faced the at the port of Islay on the coast of Peru in June perils of their further journey through the Red with a supply of plants which were placed in Sea. Although there were many casualties among Wardian cases and shipped to India via Panama the plants which were dispatched from South and the Red Sea. America, some eventually arrived safely in India. Spruce and Cross were successful in collecting From small beginnings made in 1861 the large seed and plants of C. succirubra, the red bark, plantations in the Nilgiris and in the Darjeeling from the slopes of Mt. Chimborazo, and these were district of Bengal were gradually established. shipped from Guayaquil in January 1861. Cross To Mr. Mcivor, of the Government Gardens in made several subsequent expeditions; he went to Ootacamund, and to Dr. Anderson, of the Royal the Sierra de Cajanuma from Loja in the autumn Botanic Gardens, Calcutta, the task of developing of 1861, bringing back seeds of C. officinalis; the plantations was entrusted, and Dr. Anderson twice he visited the forests of Pitayo in the extreme was succeeded by Mr. C. B. Clarke, Sir George south of Colombia to gather seed of C. pitayensis; King, and Sir David Prain. We owe to them, too, and finally, in 1877, he travelled to the upper reaches a debt of gratit1,1de. They have built up a great of the Caqueta River to obtain the seed of C. -

The Life of Charles Ledger (1818-1905)

THE LIFE OF CHARLES LEDGER (1818-1905) Fig. 1 Coat of arms of Peru, showing alpaca, cinchona and cornucopia The Life of Charles Ledger ( 1818-1905) Alpacas and Quinine Gabriele Gramiccia M MACMILLAN PRESS © Gabriele Gramiccia 1988 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1988 978-0-333-45710-8 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1956 (as amended), or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 33-4 Alfred Place, London WC1E 7DP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. First published in 1988 Additional material to this book can be downloaded from http://extra.springer.com. Published by THE MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 2XS and London Companies and representatives throughout the world ISBN 978-1-349-09951-1 ISBN 978-l-349-09949-8 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-09949-8 Contents The Figures viii The Colour Plates and Map of the Regions of South America ix Travelled by Ledger Preface X Acknowledgements xiii 1. The Early Years 1 1.1 Origins 1 1.2 Growing up in London (1818-1836) 2 1.3 First experiences in Peru from Lima to Tacna ( 1836-1844) 5 1.4 Commotion and gossip ( 1844) 14 1.5 First expeditions in search of cinchona (1844-1847) 16 1.6 A digression on llamas, alpacas, vicunas and guanacos 19 2.