Logistics and Retail Management Ii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tesco PLC Annual Report and Financial Statements 2008

212584_TESCO_REP_COVER 1/5/08 19:33 Page 1 Tesco PLC Tesco Annual Report and Financial Statements 2008 and Financial Statements Annual Report Every Little Helps More than the weekly shop www.tesco.com/annualreport08 Annual Report and Financial Statements 2008 212584_TESCO_REP_COVER 1/5/08 19:33 Page 2 Tesco PLC Tesco House Contents More than the Delamare Road Cheshunt weekly shop Hertfordshire EN8 9SL Financial highlights 1 Most people know something about Tesco. After all, we are the UK’s largest Chief Executive’s statement 2 grocer and we’ve been serving customers for the best part of a century. What you The use of the FSC logo identifies Report of the Directors 3 might not know, is that Tesco is also the products which contain wood from well-managed forests certified in > Business Review 3 world’s third largest grocery retailer with accordance with the rules of the > General information 18 operations in 12 international markets, Forest Stewardship Council. > Corporate governance 20 employing over 440,000 people and Printed on 100% recycled paper serving millions of customers every week. with FSC certification. All pulps are Elemental Chlorine Free (ECF) and Directors’ remuneration report 25 the manufacturing mill is accredited We’re not simply about providing great with the ISO 14001 standard for Financial statements 39 quality food at affordable prices. environmental management. > Statement of Directors’ Printed by CTD using an alcohol- free process. The printing inks responsibilities 40 We provide more choice than ever to are made with non-hazardous > Independent auditors’ report more customers, whether it’s through vegetable oil from renewable sources. -

Tesco Annual Report 2018

Tesco PLC Annual Report and Financial Statements 2018 Statements Financial and Report Annual PLC Tesco Serving shoppers a little better every day. Annual Report and Financial Statements 2018 WorldReginfo - 6c498727-aa42-404f-b71d-742d1ccb950a Welcome to our Annual Report. The screen icon indicates where further information is available online. We have also produced a number of short videos, available at www.tescoplc.com/ar2018. WorldReginfo - 6c498727-aa42-404f-b71d-742d1ccb950a Strategic report Tesco at a glance As a leading retailer, our 440,000(a) colleagues serve around 80 million customers every week, in more than 6,800(b) stores and online. +2.3% +2.8% +28.4% +80.6% £51.0bn∆(c) £57.5bn (c) £1,644m∆(c) £1,837m (c) Group sales Statutory revenue Group operating profit before Operating profit (2016/17: £49.9bn) (2016/17: £55.9bn) exceptional items (2016/17: £1,017m) (2016/17: £1,280m) +795.2% +62.7% +>100% +21.7% £1,298m (c) 11.88p∆(c) 12.08p (c) £2,773m∆ Statutory profit before tax Diluted EPS pre-exceptional items, Statutory diluted EPS Retail operating cash flow (2016/17: £145m) IAS 19 finance costs and IAS 39 fair (2016/17: 0.81p) (2016/17: £2,278m) value remeasurements (2016/17: 7.30p) 29.6% down ∆ Alternative performance measures (APM) Measures with this symbol ∆ are defined in the Glossary ∆(d) section of the Annual Report on pages 150 to 153. (a) Based on an actual year-end headcount. £(2.6)bn 3.0p (b) Includes franchise stores. Net debt Dividend per share (c) Reported on a continuing operations basis. -

The Role of National Culture in the Emergence Of

THE ROLE OF NATIONAL CULTURE IN THE EMERGENCE OF FINANCIAL STATEMENT FRAUD: COMPARISON OF JAPANESE AND BRITISH CULTURE IN THE CASES OF OLYMPUS AND TESCO A THESIS Presented as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements to Obtain the Bachelor Degree in Accounting Department By: Muli Wening Utami Student Number: 14312603 DEPARTMENT OF ACCOUNTING INTERNATIONAL PROGRAM FACULTY OF ECONOMICS UNIVERSITAS ISLAM INDONESIA YOGYAKARTA 2018 THE ROLE OF NATIONAL CULTURE IN THE EMERGENCE OF FINANCIAL STATEMENT FRAUD: COMPARISON OF JAPANESE AND BRITISH CULTURE IN THE CASES OF OLYMPUS AND TESCO A THESIS Presented as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements to Obtain the Bachelor Degree in Accounting Department By: Muli Wening Utami Student Number: 14312603 DEPARTMENT OF ACCOUNTING INTERNATIONAL PROGRAM FACULTY OF ECONOMICS UNIVERSITAS ISLAM INDONESIA YOGYAKARTA 2018 ii THE ROLE OF NATIONAL CULTURE IN THE EMERGENCE OF FINANCIAL STATEMENT FRAUD: COMPARISON OF JAPANESE AND BRITISH CULTURE IN THE CASES OF OLYMPUS AND TESCO A THESIS Presented as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements to Obtain the Bachelor Degree in Accounting Department By: Muli Wening Utami Student Number: 14312603 DEPARTMENT OF ACCOUNTING INTERNATIONAL PROGRAM FACULTY OF ECONOMICS UNIVERSITAS ISLAM INDONESIA YOGYAKARTA 2018 iii LEGALIZATION PAGE iv v vi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Assalamu’alaikum Warahmatullahi Wabarakatuh. All perfect praise to Allah SWT, the Lord of the World. I bear witness that none is worthy of worship but Allah, alone with no partners. And I bear witness that Muhammad SAW is His Messenger, may Allah exalt his mention. Alhamdulillahirabbil’alamin, the thesis which entitled THE ROLE OF NATIONAL CULTURE IN THE EMERGENCE OF FINANCIAL STATEMENT FRAUD: COMPARISON OF JAPANESE AND BRITISH CULTURE IN THE CASES OF OLYMPUS AND TESCO as a partial requirement to obtain the bachelor degree in Accounting Department, International Program, Faculty of Economics, Universitas Islam Indonesia is finally finished. -

Value Travels – Tesco Is About Creating Value for Customers to Earn Their Lifetime Loyalty

www.tesco.com/annualreport09 Tesco PLC Tesco PLC Tesco House Delamare Road Cheshunt Hertfordshire EN8 9SL Value Annual Report and Financial Statements 2009 travels Annual Report and Financial Statements 2009 Introduction Financial highlights 2 Chairman’s statement 3 Printed on Revive, a 100% recycled Tesco at a glance 4 paper with FSC certification. Printed by CTD using an alcohol- Chief Executive’s Q&A 5 free process. The printing inks are made with non-hazardous vegetable oil from renewable Report of the Directors 6 sources. Over 90% of solvents and developers are recycled for further Business Review 6 use and recycling initiatives are in Long-term strategy 6 place for all other waste associated Markets served and business model 7 with this production. CTD are FSC International 8 and ISO 14001 certified with strict Core UK 12 procedures in place to safeguard the Non-food 16 environment through all processes. Retailing Services 20 Designed and produced by Community 24 35 Communications. People 28 Resources and relationships 30 Group performance 32 Key Performance Indicators 36 Risks and uncertainties 38 Financial review 40 General information 41 Our Board of Directors 42 Corporate governance 44 Directors’ remuneration report 50 Financial statements 65 Statement of Directors’ responsibilities 66 Independent auditors’ report to the members of Tesco PLC 67 Group income statement 68 Group statement of recognised income and expense 69 Group balance sheet 70 Group cash flow statement 71 Reconciliation of net cash flow to movement in net debt note 71 Notes to the Group financial statements 72 Five year record 124 Tesco PLC – Parent Company financial statements 126 Independent auditors’ report to the members of Tesco PLC 136 Go online Go online Every year, more and more Every year, more and more information is available for information is available for our shareholders, staff and our shareholders, staff and customers online. -

Tesco PLC Annual R Eport and Financial S Tatements 2011 Ov 2 3

Tesco PLC Tesco Contents OverviEw 2 Financial highlights 3 Chairman’s statement 4 Chief Executive’s review 6 Our vision BuSiness reviEw* 14 Our business 16 Growing the UK core 22 To be an outstanding international retailer 26 To be strong in everything we sell 30 Growing retail services 34 Community at the heart of what we do 38 Building brands 42 Building our team 46 Property – developing and building for customers 48 Key performance indicators 50 Group financials 51 Principal risks and uncertainties 58 General information GOvernance 60 Our Board of Directors* 62 Directors’ report on corporate governance* 74 Directors’ remuneration report FiNanciaL statements 92 Statement of Directors’ responsibilities 93 Independent auditors’ report to the members of Tesco PLC 94 Group income statement 95 Group statement of comprehensive income 96 Group balance sheet 97 Group statement of changes in equity 98 Group cash flow statement 98 Reconciliation of net cash flow to movement in net debt note 99 Notes to the Group financial statements 146 Five year record 147 Tesco PLC – Parent Company balance sheet 148 Notes to the Parent Company financial statements 156 Independent auditors’ report Annual Report and Financial Statements 2011 Statements and Financial Annual Report to the members of Tesco PLC IBC Financial calendar * These sections form the Report of the Directors Tesco PLC Tesco House Delamare Road Cheshunt Hertfordshire EN8 9SL http://ar2011.tescoplc.com oVeRVIEW finanCial statements tesco around the world europe Headingfinancial calendar Revenue* -

Tesco PLC Annual Report and Financial Statements 2012 1 Worldreginfo - C47a2537-7153-4C20-B7af-Afb75d1669f4 Chairman’S Statement

Annual Report and Financial Statements 2012 WorldReginfo - c47a2537-7153-4c20-b7af-afb75d1669f4 Tesco at a glance 2011/12 We are one of the world’s largest retailers with operations in 14 countries,* employing almost 520,000 people and serving millions of customers every week. £72.0bn +7.4% £3.8bn +5.3% Group sales Group sales growth Group profit before tax Group profit before tax growth +1.6% +2.1% 14.76p Underlying profit before tax** Underlying diluted earnings Full year dividend per share per share**† UK Asia Europe Revenue± Trading profit Revenue± Trading profit Revenue± £42.8bn £2,480m £10.8bn £737m £9.9bn 66% of Group 66% of Group 17% of Group 20% of Group 15% of Group Revenue growth± Trading profit growth Revenue growth± Trading profit growth Revenue growth± +5.0% (1.0)% +10.5% +21.8% +7.3% Employees Stores Employees Stores Employees 300,373 2,979 117,015 1,719 94,409 Market position 1st Market position 1st or 2nd in all except China Market position 1st o Multiple formats Hypermarkets, superstores, Multiple formats Hypermarkets, supermarkets, Multiple formats Dep include supermarkets, convenience include convenience include supe Loyalty scheme Clubcard – around 16 million Loyalty scheme Clubcard in Malaysia and Thailand, hype active members Family Card in South Korea, Legou Loyalty scheme Club dotcom First grocery home shopping Tesco Membercard in China – over activ service 1997 20 million active members across Asia dotcom Repu dotcom South Korea 2002, planned 2011 launches in at least one major city 2012 in each market in the next few years in ea Fascia brands include: Fascia brands include: Fascia brands include: * In India, we have an exclusive franchise agreement with Trent, the retail arm of the Tata Group. -

Annual Report and Financial Statements 2016

Annual Report and Financial Statements 2016 Serving shoppers a little better every day In this report Strategic report Page Tesco at a glance 01 Introduction 02 Chairman’s statement 03 CEO’s statement 04 Turnaround priorities 06 Business model 10 KPIs: The Big 6 12 Financial review 14 Environmental and social review 20 Principal risks and uncertainties 24 Corporate governance 28 Financial statements 74 Other information 160 Watch our videos We have produced a number of short videos that are available at www.tescoplc.com/ar2016 and are featured within our report this year, as indicated by the video screen icon Tesco at a glance As one of the world’s largest retailers with reportStrategic 476,000 colleagues, we serve millions of customers every week in our stores and online. £48.4bn1 £944m1 £1,046m1 4.97p1 £(5.1)bn2 Group sales Group operating profit Statutory operating Diluted earnings per share before Net debt (exc. VAT, exc. fuel) before exceptional profit/(loss) exceptional items and net pension (14/15: £(8.5)bn) (14/15: £49.9bn) items (14/15: £940m) (14/15: £(5,750)m) finance costs (14/15: 5.46p) 1 1,3 476,000 6,902 78m1 18m Colleagues Shops around Shopping Meals donated through our food at year-end the world trips per week surplus redistribution work and (14/15: 492,000) (14/15: 6,849) (14/15: 77m) Neighbourhood Food Collection Corporate governance 2 21 17 UK & ROI % % 54 International 29 Tesco Bank 77 Group sales Group operating profit (exc. VAT, exc. fuel) before exceptional items 1 Reported on a continuing operations basis. -

Serving Shoppers a Little Better Every Day. Our Values

Tesco PLC Annual Report and Financial Statements 2020 Serving shoppers a little better every day. Annual Report and Financial Statements 2020 Contents Strategic report. 2020 highlights ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................1 Chairman’s statement ..............................................................................................................................................................................2 Group Chief Executive’s review ....................................................................................................................................3 Strategic review ...........................................................................................................................................................................................................4 Our business model ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Financial review .............................................................................................................................................................................................................7 Key performance indicators ................................................................................................................................................12 -

Annual Report and Financial Statements 2016

Annual Report and Financial Statements 2016 Serving shoppers a little better every day WorldReginfo - 42c33a9f-18b8-4e58-a6b9-8ff9dae01895 In this report Strategic report Page Tesco at a glance 01 Introduction 02 Chairman’s statement 03 CEO’s statement 04 Turnaround priorities 06 Business model 10 KPIs: The Big 6 12 Financial review 14 Environmental and social review 20 Principal risks and uncertainties 24 Corporate governance 28 Financial statements 74 Other information 160 Watch our videos We have produced a number of short videos that are available at www.tescoplc.com/ar2016 and are featured within our report this year, as indicated by the video screen icon WorldReginfo - 42c33a9f-18b8-4e58-a6b9-8ff9dae01895 Tesco at a glance As one of the world’s largest retailers with reportStrategic 476,000 colleagues, we serve millions of customers every week in our stores and online. £48.4bn1 £944m1 £1,046m1 4.97p1 £(5.1)bn2 Group sales Group operating profit Statutory operating Diluted earnings per share before Net debt (exc. VAT, exc. fuel) before exceptional profit/(loss) exceptional items and net pension (14/15: £(8.5)bn) (14/15: £49.9bn) items (14/15: £940m) (14/15: £(5,750)m) finance costs (14/15: 5.46p) 1 1,3 476,000 6,902 78m1 18m Colleagues Shops around Shopping Meals donated through our food at year-end the world trips per week surplus redistribution work and (14/15: 492,000) (14/15: 6,849) (14/15: 77m) Neighbourhood Food Collection Corporate governance 2 21 17 UK & ROI % % 54 International 29 Tesco Bank 77 Group sales Group operating profit (exc. -

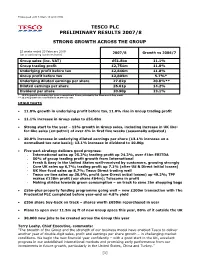

Tesco Plc Preliminary Results 2007/8

Embargoed until 7.00am 15 April 2008 TESCO PLC PRELIMINARY RESULTS 2007/8 STRONG GROWTH ACROSS THE GROUP 52 weeks ended 23 February 2008 2007/8 Growth vs 2006/7 (on a continuing business basis) Group sales (inc. VAT) £51.8bn 11.1% Group trading profit £2,751m 11.0% Underlying profit before tax £2,846m 11.8% Group profit before tax £2,803m 5.7%* Underlying diluted earnings per share 27.02p 20.8%** Diluted earnings per share 26.61p 14.2% Dividend per share 10.90p 13.1% * 15.3% growth excluding last year’s exceptional items; principally the Pensions A-Day credit ** 13.1% growth on a normalised 28.9% tax rate HIGHLIGHTS x 11.8% growth in underlying profit before tax, 11.0% rise in Group trading profit x 11.1% increase in Group sales to £51.8bn x Strong start to the year – 13% growth in Group sales, including increase in UK like- for-like sales (ex-petrol) of over 4% in first five weeks (seasonally adjusted) x 20.8% increase in underlying diluted earnings per share (13.1% increase on a normalised tax rate basis); 13.1% increase in dividend to 10.90p x Five-part strategy delivers good progress: - International sales up 25.3%; trading profit up 24.3%, over £1bn EBITDA - 50% of group trading profit growth from International - Fresh & Easy in the United States well-received by customers, growing strongly - Core UK sales up 6.7%; trading profit up 7.1% (after US & Direct initial losses) - UK Non-food sales up 8.7%; Tesco Direct trading well - Tesco on-line sales up 30.9%, profit (pre-Direct initial losses) up 49.2%; TPF makes £128m profit (our share -

Tesco PLC Annual Report and Financial Statements 2012 1 Chairman’S Statement

Annual Report and Financial Statements 2012 Tesco at a glance 2011/12 We are one of the world’s largest retailers with operations in 14 countries,* employing almost 520,000 people and serving millions of customers every week. £72.0bn +7.4% £3.8bn +5.3% Group sales Group sales growth Group profit before tax Group profit before tax growth +1.6% +2.1% 14.76p Underlying profit before tax** Underlying diluted earnings Full year dividend per share per share**† UK Asia Europe Revenue± Trading profit Revenue± Trading profit Revenue± £42.8bn £2,480m £10.8bn £737m £9.9bn 66% of Group 66% of Group 17% of Group 20% of Group 15% of Group Revenue growth± Trading profit growth Revenue growth± Trading profit growth Revenue growth± +5.0% (1.0)% +10.5% +21.8% +7.3% Employees Stores Employees Stores Employees 300,373 2,979 117,015 1,719 94,409 Market position 1st Market position 1st or 2nd in all except China Market position 1st o Multiple formats Hypermarkets, superstores, Multiple formats Hypermarkets, supermarkets, Multiple formats Dep include supermarkets, convenience include convenience include supe Loyalty scheme Clubcard – around 16 million Loyalty scheme Clubcard in Malaysia and Thailand, hype active members Family Card in South Korea, Legou Loyalty scheme Club dotcom First grocery home shopping Tesco Membercard in China – over activ service 1997 20 million active members across Asia dotcom Repu dotcom South Korea 2002, planned 2011 launches in at least one major city 2012 in each market in the next few years in ea Fascia brands include: Fascia brands include: Fascia brands include: * In India, we have an exclusive franchise agreement with Trent, the retail arm of the Tata Group. -

Tesco Versus Sainsbury's Growth Strategies and Corporate Competitiveness 1990-2007

Tesco versus Sainsbury’s Growth Strategies and Corporate Competitiveness 1990-2007 Case study Reference no 308-065-1 This case was written by Markus Kreutzer and Professor Dr Christoph Lechner, University of St Gallen. It is intended to be used as the basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of a management situation.The case was compiled from published sources. © 2008, University of St Gallen. No part of this publication may be copied, stored, transmitted, reproduced or distributed in any form or medium whatsoever without the permission of the copyright owner. Distributed by ecch, UK and USA North America Rest of the world www.ecch.com t +1 781 239 5884 t +44 (0)1234 750903 ecch the case for learning All rights reserved f +1 781 239 5885 f +44 (0)1234 751125 Printed in UK and USA e [email protected] e [email protected] 308-065-1 INTRODUCTION In 2008, the UK-based international food and general merchandising retailer Tesco reached a market share of about 30% in the UK, roughly the same as its rivals Sainsbury’s and ASDA combined. Tesco has greatly diversified, extending its business lines from food into non-food, clothing, financial services, and telecommunications. It ranks sixth in the international retail market behind Wal-Mart (US), Carrefour (France), Home Depot (US), Metro (Germany), and Royal Ahold (Netherlands).1 Tesco was not always the dominant player it is today. In 1990, it was a mid-sized food chain far behind its rival, Sainsbury’s. Starting in the 1990s, it pursued a broad set of growth initiatives, steadily increasing its market share and gaining importance.