Serial Shakespeare: Intermedial Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Study Guide 2016 Study Guide

2016 STUDY GUIDE 2016 STUDY GUIDE EDUCATION PROGRAM PARTNER AS YOU LIKE IT BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE DIRECTOR JILLIAN KEILEY TOOLS FOR TEACHERS sponsored by PRODUCTION SUPPORT is generously provided by M. Fainer and by The Harkins/Manning Families In Memory of James & Susan Harkins INDIVIDUAL THEATRE SPONSORS Support for the 2016 Support for the 2016 Support for the 2016 Support for the 2016 season of the Festival season of the Avon season of the Tom season of the Studio Theatre is generously Theatre is generously Patterson Theatre is Theatre is generously provided by provided by the generously provided by provided by Claire & Daniel Birmingham family Richard Rooney & Sandra & Jim Pitblado Bernstein Laura Dinner CORPORATE THEATRE PARTNER Sponsor for the 2016 season of the Tom Patterson Theatre Cover: Cyrus Lane, Petrina Bromley. Photography by Don Dixon. Table of Contents The Place The Stratford Festival Story ........................................................................................ 1 The Play The Playwright: William Shakespeare ........................................................................ 3 A Shakespearean Timeline ......................................................................................... 4 Plot Synopsis ............................................................................................................... 6 Cast of Characters ...................................................................................................... 7 Sources, Origins and Production History .................................................................. -

Stars, Genres, and the Question of Constructing a Popular Anglophone Canadian Cinema in the Twenty First Century

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-20-2012 12:00 AM Fighting, Screaming, and Laughing for an Audience: Stars, Genres, and the Question of Constructing a Popular Anglophone Canadian Cinema in the Twenty First Century Sean C. Fitzpatrick The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Christopher E. Gittings The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Film Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Sean C. Fitzpatrick 2012 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Fitzpatrick, Sean C., "Fighting, Screaming, and Laughing for an Audience: Stars, Genres, and the Question of Constructing a Popular Anglophone Canadian Cinema in the Twenty First Century" (2012). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 784. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/784 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FIGHTING, SCREAMING, AND LAUGHING FOR AN AUDIENCE: STARS, GENRE, AND THE QUESTION OF CONSTRUCTING A POPULAR ANGLOPHONE CANADIAN CINEMA IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY (Spine title: Fighting, Screaming, and Laughing for an Audience) (Thesis format: Monograph OR Integrated-Article) by Sean Fitzpatrick Graduate Program in Film Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Sean Fitzpatrick 2012 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION Supervisor Examiners ______________________________ ______________________________ Dr. -

GGPAA Gala Program 2015 English

NatioNal arts CeNtre, ottawa, May 30, 2015 The arts engage and inspire us A nation’s ovation. We didn’t invest a lifetime perfecting our craft. Or spend countless hours on the road between performances. But as a proud presenting sponsor of the Governor General’s Performing Arts Awards, we did put our energy into recognizing outstanding Canadian artists who enrich the fabric of our culture. When the energy you invest in life meets the energy we fuel it with, Arts Nation happens. ’ work a O r i Explore the laureates’’ work at iTunes.com/GGPAA The Governor General’s Performing Arts Awards The Governor General’s Performing Arts Recipients of the National arts Centre award , Awards are Canada’s most prestigious honour which recognizes work of an extraordinary in the performing arts. Created in 1992 by the nature in the previous performance year, are late Right Honourable Ramon John Hnatyshyn selected by a committee of senior programmer s (1934–2002), then Governor General of from the National Arts Centre (NAC). This Canada, and his wife Gerda, the Awards are Award comprises a commemorative medallion, the ultimate recognition from Canadians for a $25,000 cash prize provided by the NAC, and Canadians whose accomplishments have a commissioned work created by Canadian inspired and enriched the cultural life of ceramic artist Paula Murray. our country. All commemorative medallions are generously Laureates of the lifetime artistic achievement donated by the Royal Canadian Mint . award are selected from the fields of classical The Awards also feature a unique Mentorship music, dance, film, popular music, radio and Program designed to benefit a talented mid- television broadcasting, and theatre. -

Men with Brooms

MEL GIBSON, JODIE FOSTER AND OTHER STARS PUT OSCAR IN ITS PLACE ROCK POSTER INSIDE! canada’s #1 movie magazine in canada’s #1 theatres march 2002 | volume 3 | number 3 PAUL GROSS LEADS MEN WITH BROOMS JOHN LEGUIZAMO SPEAKS FOR ICE AGE BEST BETS FOR OSCAR ROCK DWAYNE “THE ROCK” JOHNSONKING TALKS ABOUT LEAPING FROM THE! WRESTLING RING TO HOLLYWOOD FOR THE SCORPION KING $3.00 plus NEW VIDEO AND DVD | HOROSCOPE | WEB | MUSIC | VIDEOGAMES | CARLA COLLINS contents Famous | volume 3 | number 3 | 38 28 18 FEATURES DEPARTMENTS COLUMNS 18 GROSS NATIONAL PRODUCT 06 EDITORIAL 08 HEARSAY Great White Hunk Paul Gross makes Gwyneth earns a few coins his directorial debut with, of all things, 10 SHORTS a romantic “dramedy” about curling. Darth meets Gandalf, movies shooting 36 LINER NOTES Here, the former Due South star talks in Canada and Edmonton’s Local Alanis Morissette goes it alone on about his fear of being behind the Heroes film fest her new album camera for Men with Brooms, and the challenge of making popular Canadian 12 THE BIG PICTURE 38 NAME OF THE GAME films | By Marni Weisz The Time Machine, Resident Evil, Sonic battles back We Were Soldiers, The Panic Room 26 LEG WORK and Full Frontal hit theatres 40 BIT STREAMING Never-predictable actor and cartoon Steal this article. We dare you buff John Leguizamo talks about 16 THE PLAYERS putting his voice behind the animated What’s the deal with Jon Stewart adventure Ice Age | By Earl Dittman and Guy Pearce? 28 IN SEARCH OF OSCAR 32 TRIVIA Stop! Don’t place that Oscar bet until Name Ice Cube’s first screenplay you’ve seen which 2001 films got the nod from the AFI, the Toronto Film 34 ON THE SLATE Critics and the Golden Globes Tarantino gets back to work, Altman reunites with some old pals COVER STORY 42 FIVE FAVOURITE FILMS 30 ON THE ROCK Eddie McClintock makes his picks He’s come a long way since he slept on a stained, stolen mattress and played 43 VIDEO AND DVD for the Calgary Stampeders. -

Wilby Wonderful

Wilby Wonderful A film by Daniel MacIvor Running Time: 99 min. Distributor Contact: Josh Levin Film Movement Series 109 W. 27th St., Suite 9B, New York, NY 10001 Tel: 212-941-7744 ext. 213 Fax: 212-941-7812 [email protected] SYNOPSIS Wilby Wonderful is a bittersweet comedy about the difference a day makes. Over the course of twenty-four hours, the residents of the tiny island town of Wilby try to maintain business as a sex scandal threatens to rock the town to its core. The town’s video store owner, Dan Jarvis (James Allodi) – depressed over the pending revelations about his love life – decides to end it all, but keeps getting interrupted by Duck MacDonald (Callum Keith Rennie), the town’s dyslexic sign-painter, during his half-hearted suicide attempts. Meanwhile, Dan has enlisted blindly ambitious real estate agent Carol French (Sandra Oh) to sell his house in an effort to quickly tie up the last of his loose ends. Carol, however, is more interested in selling her recently deceased mother-in-law’s house to Mayor Brent Fisher (Maury Chaykin), in order to get in with the in-crowd. To take her social step up, Carol could use the help of her police officer husband Buddy (Paul Gross), but Buddy has his hands full with sexy, wrong-side-of-the-tracks Sandra Anderson (Rebecca Jenkins), who can never decide if she is coming or going. Sandra’s daughter Emily (Ellen Page), is none too thrilled about her mother repeating her typical pattern of married men and bad reputation, but Emily herself is just about to have her heart broken for the very first time. -

'Good Witch' Production Bios Orly Adelson

‘GOOD WITCH’ PRODUCTION BIOS ORLY ADELSON (Executive Producer) – Since the formation of Orly Adelson Productions in 1995, Orly Adelson has become recognized as one of the most prominent and distinguished producers in the television and film industry and has also been recognized as one of the 100 most powerful people in sports in America by the Sports Business Journal. Utilizing Orly Adelson Productions’ ability to finance multiple projects worldwide, she has created a dynamic production company, boasting a diverse and eclectic slate of high profile entertainment, including the company’s upcoming first ventures into the world of animated and musical films. The company recently produced “Ruffian,” which chronicles the greatest female racehorse of all time, which premiered on ABC to critical reviews and will soon begin showing on ESPN, ESPN.com, Mobile ESPN and ESPN Motion. Other projects for ESPN have included “3,” which starred Barry Pepper as NASCAR hero Dale Earnhardt and debuted as the network’s highest- rated movie ever and the second-highest rated basic cable movie of the year, “Code Breakers,” which was nominated for a CSC Award as well as an Eddie Award, “Tilt,” an ESPN series centered around the volatile world of high stakes poker starring Michael Madsen and Eddie Cibrian, “The Junction Boys” and “Playmakers,” which was ESPN’s first original dramatic series. Other highly publicized, award-winning projects produced by Orly Adelson Productions include “Cavedweller,” which was based on the novel by Dorothy Allison and premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival, “DC Sniper: 23 Days of Fear,” “The Truth About Jane,” which garnered the highest ratings for Lifetime in five years and “Plainsong,” an adaptation of the National Book Award finalist for Hallmark Hall of Fame. -

National Arts Centre, Ottawa, April 27 Centre National Des Arts, Ottawa, 27 Avril 27 Ottawa, Arts, Des National Centre

NATIONAL ARTS CENTRE, OTTAWA, APRIL 27 CENTRE NATIONAL DES ARTS, OTTAWA, 27 AVRIL 27 OTTAWA, ARTS, DES NATIONAL CENTRE THE ARTS ENGAGE AND INSPIRE US PREMIUM SERVICE THAT STRIKES A CHORD At Air Canada, we strive to perform at the highest level in everything we do. That’s why we’ve put so much care into our premium products and services. Book Air Canada Signature Class to enjoy a range of enhanced amenities and exclusive onboard products. Settle into a fully lie-fl at seat, while savouring a delicious meal by chef David Hawksworth and premium wine selection by sommelier Véronique Rivest. Air Canada Signature Service is available on select fl ights aboard our Boeing 787, 777 and 767 aircraft and our Airbus A330 aircraft. Learn more at aircanada.ca/signatureservice Air Canada is proud to be the Presenting Sponsor of the 2019 Governor General’s Performing Arts Awards and to recognize the outstanding Canadian talent contributing to culture in Canada and abroad. PREMIUM SERVICE THAT STRIKES A CHORD At Air Canada, we strive to perform at the highest level in everything we do. That’s why we’ve put so much care into our premium products and services. Book Air Canada Signature Class to enjoy a range of enhanced amenities and exclusive onboard products. Settle into a fully lie-fl at seat, while savouring a delicious meal by chef David Hawksworth and premium wine selection by sommelier Véronique Rivest. Air Canada Signature Service is available on select fl ights aboard our Boeing 787, 777 and 767 aircraft and our Airbus A330 aircraft. -

Paul Gross's Men with Brooms by Cynthia Amsden

CANADIAN Paul Gross's Men with Brooms BY Cynthia Amsden If there is such a thing as a comedic Zeitgeist in this country, we are expe- riencing it now. Canada is known for its art—house fodder. "Introspective, dark, moody, personal, artistic films," says Seaton McLean, president of Alliance Atlantis. And lest we forget the other hallmark of Canadian film, the world knows us for weird sex. 5 ?.• 5_ Tz Suddenly, as if springing forth fully formed from the brow of Athena .g 0 comes not one, but two Canadian comedies striving for the unholy glory of being successful mall movies. Blue plate specials. From Paris to 57, Palookaville, on a non—stop trip, and dammit, we are going to be com- mercially triumphant — for a change. noo 0 0 a '13 Q Men with Brooms directed, co-written and starring Paul Gross 8 MARCH 2002 COMEDY, eh? ...and Steve Smith's Red Green's Duct Tape Forever Men with Brooms, the Paul Gross fiesta, and Red Green's Duct Tape Forever, Steve Smith's Red Green extravaganza, are slated to hit the theatres within weeks of each other this spring. Go ahead. Say it. There's no such thing as a coincidence. Both Gross and Smith are leapfrogging to the big screen from tele- vision. Both Smith and Gross are new to the feature—film environment, and both had debut filmmaker epiphanies which — accompanied by forehead slaps — sounded like. "Ohhh, this is what it's all about." So, if not a coincidence, then what is this? One could reasonably answer: it's about time. -

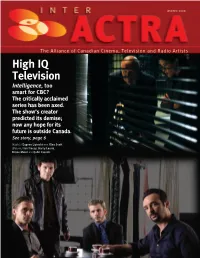

High IQ Television Intelligence, Too Smart for CBC? the Critically Acclaimed Series Has Been Axed

WINTER 2008 The Alliance of Canadian Cinema, Television and Radio Artists High IQ Television Intelligence, too smart for CBC? The critically acclaimed series has been axed. The show’s creator predicted its demise; now any hope for its future is outside Canada. See story, page 6 (Right:) Eugene Lipinski and Klea Scott. (Below:) Ian Tracey, Darcy Laurie, Shane Meier and John Cassini. 55023-1 Interactra.indd 1 3/13/08 10:56:25 AM By Richard Hardacre How do I know thee? Let me count the ways.(1) With some taxi drivers there’s much I had indeed piqued his interest. He Negotiating Committee will be counting more than meets the eye. If, like me, you told me that he’d been a professional on your support. We will achieve the very happen to have conversations with many Engineer in his native Morocco. He asked best deal for you that we possibly can – we of them between the Ottawa airport or me if I had been on strike last winter, are not new to this world now. train station and various Committee and he wondered what that was all about. Negotiating our collective agreements, rooms, Ministers’ offices, anterooms of When I explained how we could not just and building the campaign for Canadian bureaucrats around Parliament Hill, well accept a ‘kiss-off’ for our work distributed film and television programming are two then you occasionally might tune into an throughout the globe via new media, and of the biggest priorities of ACTRA. interesting frequency. that contrary to the honchos of the asso- As there will also likely be a Federal On one slushy, rush-hour, after I began ciations of producers, there was indeed election looming soon, we will make the in Canada’s other official language, my money being generated on the Internet, issues of foreign ownership limits on our cabbie inquired about my occupation. -

PRESENTS a RHOMBUS MEDIA and BEST BOY ENTERTAINMENT

PRESENTS WRITTEN and DIRECTED by STEPHEN DUNN a RHOMBUS MEDIA and BEST BOY ENTERTAINMENT production US DISTRIBUTOR www.strandreleasing.com HEAD OFFICE 6140 W Washington Blvd Culver City, CA 90232 USA Phone: +1 310 836 7500 Fax: +1 310 836 7510 E-mail: [email protected] by Stephen Dunn Canada, 2015, 90 minutes, English, Coming-of-Age Drama Elevation Pictures presents a Rhombus Media and Best Boy Entertainment production, written and directed by Stephen Dunn and starring Connor Jessup (BLACKBIRD, FALLING SKIES) in the coming of age drama, CLOSET MONSTER. Also starring in the film are Aaron Abrams (HANNIBAL, YPF), Joanne Kelly (WAREHOUSE 13, HOSTAGES), Aliocha Schneider (THREE NIGHT STAND), Jack Fulton (LIFE, PAY THE GHOST), Sofia Banzhaf (SILENT RETREAT), Mary Walsh (THE HOUR HAS 22 MINUTES, THE GRAND SEDUCTION), and Isabella Rossellini (BLUE VELVET, ENEMY) as a talking hamster named Buffy. CLOSET MONSTER tells the story of Oscar Madly (Jessup), a creative and driven teenager who hovers on the brink of adulthood. Destabilized by his dysfunctional parents, unsure of his sexuality, and haunted by horrific images of a tragic gay bashing he witnessed as a child, Oscar dreams of escaping the town he feels is suffocating him. A talking hamster, imagination and the prospect of love help him confront his surreal demons and discover himself. CLOSET MONSTER marks the debut feature film for writer/director Stephen Dunn (POP UP PORNO, WE WANTED MORE, LIFE DOESN’T FRIGHTEN ME). The film is an official Ontario-Newfoundland co-production, produced by Kevin Krikst (METHOD, PARACHUTE) and Fraser Ash (DUST) of Rhombus Media in Toronto and Edward J. -

The Man Who Invented Christmas Pk

THE MAN WHO INVENTED CHRISTMAS Directed by Bharat Nalluri Starring Dan Stevens, Christopher Plummer and Jonathan Pryce UK release date | 1st December 2017 Running time | 104 minutes Certificate | PG Press information | Saffeya Shebli | [email protected] | 020 7377 1407 1 OFFICIAL SYNOPSIS The Man Who Invented Christmas tells of the magical journey that led to the creation of Ebenezer Scrooge (Christopher Plummer), Tiny Tim and other classic characters from A Christmas Carol. Directed by Bharat Nalluri (Miss Pettigrew Lives for a Day), the film shows how Charles Dickens (Dan Stevens) mixed real life inspirations with his vivid imagination to conjure up unforgettable characters and a timeless tale, forever changing the holiday season into the celebration we know today. LONG SYNOPSIS The bestselling writer in Victorian London sets out to revive his flagging career and reimagines Yuletide celebrations in The Man Who Invented Christmas, an entertaining and enchanting glimpse into the life and mind of master storyteller Charles Dickens as he creates the quintessential holiday tale, A Christmas Carol. After a string of successful novels, world-renowned writer Dickens (Dan Stevens) has had three flops in a row. With the needs of his burgeoning family and his own extravagance rapidly emptying his pockets, Dickens grows desperate for another bestseller. Tormented by writer’s block and at odds with his publishers, he grasps at an idea for a surefire hit, a Christmas story he hopes will capture the imagination of his fans and solve his financial problems. But with only six weeks to write and publish the book before the holiday, and without the support of his publishers – who question why anyone would ever read a book about Christmas – he will have to work feverishly to meet his deadline. -

ACTRA Dying a Dramatic Death? Canadian Culture

30481 InterACTRA spring 4/2/03 1:11 PM Page 1 Spring 2003 The Alliance of Canadian Cinema, Television and Radio Artists Muzzling Culture What trade agreements have to do with actors PAGE 8 30481 InterACTRA spring 4/2/03 1:11 PM Page 2 Happy Birthday… ACTRA Thor Bishopric CTRA marks its 60th anniversary in But ACTRA can’t do its job fighting on improvements, protecting existing gains, A2003 – celebrating 60 years of great behalf of our members if our resources are while assuring everyone from here to Canadian performances, 60 years con- dwindling. Your decision to strengthen Hollywood that we too want to maintain tributing to and fighting for Canadian ACTRA means we can remain focused stability in our industry. culture and 60 years of advances in pro- and effective in our efforts. The additional And on one final celebratory note, tecting performers. All members should be resources will be directed toward core National Councillor Maria Bircher and very proud of our organization’s tenacity activities such as the fight for Canadian I are beaming with pride over another and grateful to those members who came production, bargaining, and the continued birthday – that of our daughter Teale before us and ensured ACTRA’s success. collection of Use Fees through ACTRA Miranda Bishopric. Teale arrived at In February, ACTRA Toronto kicked PRS. Please see page 6 for more on the St. Mary’s Hospital in Montreal on off our 60th in style by presenting three referendum. February 16th at 10:26 p.m. She was born ACTRA Awards at a reception at the By the time you read this, we will in perfect health.