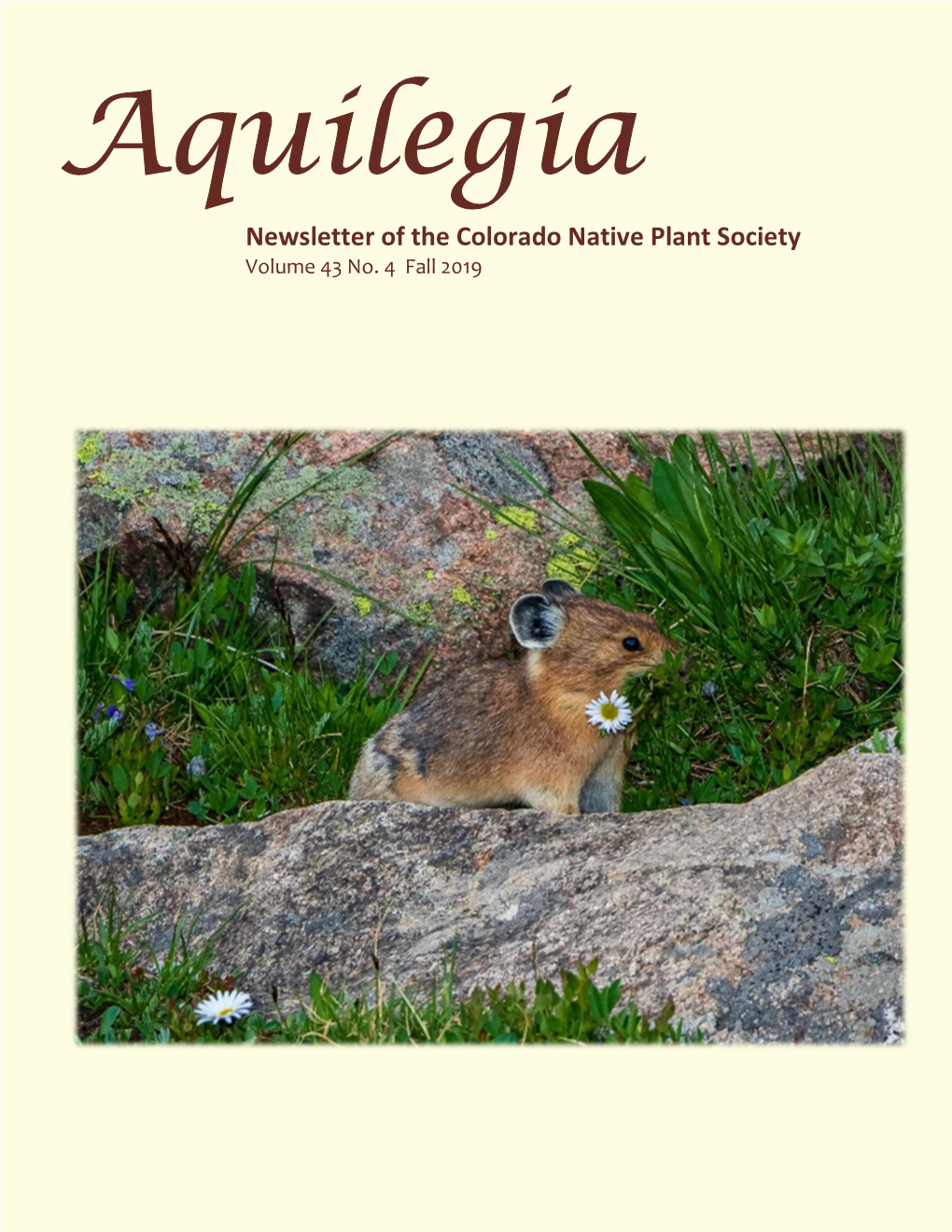

Aquilegia 2019 Fall Volume 43-4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

Colorado Wildlife Action Plan: Proposed Rare Plant Addendum

Colorado Wildlife Action Plan: Proposed Rare Plant Addendum By Colorado Natural Heritage Program For The Colorado Rare Plant Conservation Initiative June 2011 Colorado Wildlife Action Plan: Proposed Rare Plant Addendum Colorado Rare Plant Conservation Initiative Members David Anderson, Colorado Natural Heritage Program (CNHP) Rob Billerbeck, Colorado Natural Areas Program (CNAP) Leo P. Bruederle, University of Colorado Denver (UCD) Lynn Cleveland, Colorado Federation of Garden Clubs (CFGC) Carol Dawson, Bureau of Land Management (BLM) Michelle DePrenger-Levin, Denver Botanic Gardens (DBG) Brian Elliott, Environmental Consulting Mo Ewing, Colorado Open Lands (COL) Tom Grant, Colorado State University (CSU) Jill Handwerk, Colorado Natural Heritage Program (CNHP) Tim Hogan, University of Colorado Herbarium (COLO) Steve Kettler, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) Andrew Kratz, U.S. Forest Service (USFS) Sarada Krishnan, Colorado Native Plant Society (CoNPS), Denver Botanic Gardens Brian Kurzel, Colorado Natural Areas Program Eric Lane, Colorado Department of Agriculture (CDA) Paige Lewis, The Nature Conservancy (TNC) Ellen Mayo, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Mitchell McGlaughlin, University of Northern Colorado (UNC) Jennifer Neale, Denver Botanic Gardens Betsy Neely, The Nature Conservancy Ann Oliver, The Nature Conservancy Steve Olson, U.S. Forest Service Susan Spackman Panjabi, Colorado Natural Heritage Program Jeff Peterson, Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT) Josh Pollock, Center for Native Ecosystems (CNE) Nicola Ripley, -

Leading Botanists in San Diego Nancy Carol Carter

Journal of the California Garden & Landscape History Society Vol. 14, No. 4 • Fall 2011 The Brandegees: Leading Botanists in San Diego Nancy Carol Carter [This article, originally published in The Journal of San Diego History, is reprinted here, by permission, in a somewhat abridged form.1] he most renowned botanical couple of 19th-century and generally agreeing with his scientific principles, the T America lived in San Diego from 1894 until 1906. Brandegees eventually claimed a superior ability to classify They were early settlers in the Bankers Hill area, initially and appropriately name the plants they had collected and constructing a brick herbarium to house the world’s best observed in situ. Fully aware of delays and impatient with private collection of plant specimens from the western the imprecision of more distant classification work, both United States and Mexico. They lived in a tent until their resisted the tradition of submitting new species to Gray or treasured plant collection was properly protected, then built other East Coast scientists for botanical description.3 They a house connected to the herbarium. Around their home became expert taxonomists who described and defended they established San Diego’s first botanical garden—a col- their science in West Coast journals. During their lifetimes, lection of rare and exotic plants that furthered their research the Brandegees published a combined total of 159 scientific and delighted visitors. papers.4 Their example in- Botanists and plant ex- spired other Pacific Coast perts from around the botanists to greater confidence world knew of this garden in their own field experience and traveled to San Diego and the value of botanically to study its plants. -

Food Festival Mungo National Park Gabrielle Chanel

FOOD FESTIVAL in Australia A Guide to MUNGO NATIONAL PARK Edition GABRIELLE 39 CHANEL. Spring Fashion Manifesto 2021 Image Credit: Jimmy Emms WELCOME! RESERVATIONS As we approach spring we are a road trip, starting in Griffith the gourmet capital of the region. & ENQUIRIES looking forward to improved weather and some long standing If you havent already I encourage you to join events that we have all missed. our new Sharp Traveller Club which replaces CALL 1300 55 66 94 the Sharp Flyer Programme. If you have sharpairlines.com.au I am looking forward to the events featured any questions in relation to our new system in this edition including the Sydney Hobart please do not hesitate to call our friendly Yacht Race, Melbourne Jazz Festival, and the reservations team on 1300 55 66 94 HEAD OFFICE Festival of King Island. If you are on Flinders 44 Gray Street Island during this time you maybe lucky Hamilton Victoria 3300 Take care and stay safe. T: 1300 55 66 94 enough to see the Yacht passing on their way E: [email protected] to the finish. Or if you prefer to get out and explore our Malcolm Sharp great country, the Riverina Region and the MANAGING DIRECTOR LIKE TO ADVERTISE? southwest of New South Wales is ideal for Editorial & Advertising Contact Heidi Jarvis T: 0438 778 161 E: [email protected] In This Edition GET UP CLOSE DISCOVER THE MELBOURNE & INTIMATE 22 FASCINATING INTERNATIONAL UNDERGROUND 4 JAZZ FESTIVAL 34 OF TASMANIA MUSIC FOR FOOD THE SENSES FESTIVAL MUSIC TO IN AUSTRALIA 8 YOUR EARS 40 A GUIDE TO MUNGO A TASTE 12 NATIONAL PARK 42 OF SALT KILLIECRANKIE CONTEMPORARY WEARABLES 44 ROLEX DOWN SYDNEY HOBART GABRIELLE CHANEL. -

We Are All Around Us by Amy King

We Are All Around Us Amy King Editing Booth Give unto feet their water; watch people enjoy their figures on film. My lyrics before death were written on parchment long ago. It’s time to undo the town: suck the glue from my road, erase the lawn in my garden, unsew the bait I have mistaken for luck. My anchor pretends a hope that keeps the sky awash in blue. Enough guilt from this fist made of rubber: Camus must meet his Kafka; Kundera will wash the back of Haushofer; Cassandra seeks her mother Wolf. Black scent pervades and sweetens the room. My estrangement burns and falls away. I mix it with dough as bread for the masses, an antidote grain. They throw themselves apart. If I were you, I would wait for me. The dispersed crowd gathers round; they wish away clarity and chant for new instruments of attention. Hair grows from my chest. People speak in hybrid tongues. Rivers rise, coercing the moss to share its lightning and we each become electrical timings in the bioluminescent show. We Are All Around Us Skin awakens to sing inside its flesh. I am a photo of the sunrise. My liver coordinates with the man across the sidewalk. He wears a red scarf. We stand at this juncture without nodding our presence. Each hand adjusts the seams in our separate pants. A few Germans and French pass in the vicinity. This plan can easily be witnessed for it is held in New York City. It is the reason the city exists this morning. -

Crested Butte Wildflower Guide

LUPINE, SILVERY Wildflowers Shrubs Lupinus argenteus C C D D S S GOLDENEYE, SHOWY GOLDENWEED, SNEEZEWEED, ORANGE LOVAGE, PORTER'S ELEPHANTELLA FITWEED, CASE'S ROSE, WILD SNOWBERRY CINQUEFOIL, SHRUBBY HOLLY GRAPE Heliomeris multiflora CURLYHEAD Hymenoxys hoopesii OR OSHA ELEPHANT'S HEAD Corydalis caseana brandegei Rosa woodsii Symphoricarpos Potentilla fructicosa Mahonia repens Contributors Pyrrocoma crocea Ligusticum porteri Pedicularis groenlandica rotundifulius Vincent Rossignol The Handy Dandy ■ BS Landscape Architecture Kansas State University 1965 Wildflower Guide C C D S S S ■ Gunnison County resident since 1977 ■ Crested Bue Wildflower Fesval Tour leader from A PHOTO GUIDE TO POPULAR 19912002 WILDFLOWERS AND SHRUBS BLOOMING ■ Field Biologist Plants: US Forest Service and Bureau of IN AND NEAR CRESTED BUTTE Land Management; Gunnison, Colorado. Summer Seasonal: 19952011 Rick Reavis Wildflower Fesval Board Member The Crested Bue Wildflower Fesval is Rick has been exploring and idenfying nave and dedicated to the conservaon, preservaon and introduced plants around the Crested Bue area since appreciaon of wildflowers through educaon 1984. Rick is a 27year former business owner of an award and celebraon. We are commied to winning landscape development company. As an Associate protecng our natural botanical heritage for ARNICA, HEARTLEAF LILY, GLACIER OR SNOW SUNFLOWER, MULE'S EARS LUPINE, SILVERY LARKSPUR, DWARF MONKSHOOD ELDERBERRY, RED KINNIKINNIK HONEYSUCKLE, WILLOW, YELLOW Professor at Oklahoma State University, Oklahoma City, he future generaons and promong sound Arnica cordifolia Erythronium grandiflorum Wyethia amplexicaulis Lupinus argenteus Delphinium nuttallianum Aconitum columbianum Sambucus racemosa Arctostaphylos uva-ursi TWINBERRY Salix lutea spent several years teaching classes in plant idenficaon, stewardship of this priceless resource. Lonicera involucrata landscape maintenance and general horculture. -

Alplains 2013 Seed Catalog P.O

ALPLAINS 2013 SEED CATALOG P.O. BOX 489, KIOWA, CO 80117-0489, U.S.A. Three ways to contact us: FAX: (303) 621-2864 (24 HRS.) email: [email protected] website: www.alplains.com Dear Growing Friends: Welcome to our 23rd annual seed catalog! The summer of 2012 was long, hot and brutal, with drought afflicting most of the U.S. Most of my botanical explorations were restricted to Idaho, Wash- ington, Oregon and northern California but even there moisture was below average. In a year like this, seeps, swales, springs, vestigial snowbanks and localized rainstorms became much more important in my search for seeding plants. On the Snake River Plains of southern Idaho and the scab- lands of eastern Washington, early bloomers such as Viola beckwithii, V. trinervata, Ranunculus glaberrimus, Ranunculus andersonii, Fritillaria pudica and Primula cusickiana put on quite a show in mid-April but many populations could not set seed. In northern Idaho, Erythronium idahoense flowered extensively, whole meadows were covered with thousands of the creamy, pendant blossoms. One of my most satisfying finds in the Hells Canyon area had to be Sedum valens. The tiny glaucous rosettes, surround- ed by a ring of red leaves, are a succulent connoisseur’s dream. Higher up, the brilliant blue spikes of Synthyris missurica punctuated the canyon walls. In southern Oregon, the brilliant red spikes of Pedicularis densiflora lit up the Siskiyou forest floor. Further north in Oregon, large populations of Erythronium elegans, Erythronium oregonum ssp. leucandrum, Erythro- nium revolutum, trilliums and sedums provided wonderful picture-taking opportunities. Eriogonum species did well despite the drought, many of them true xerics. -

2017 RISE Symposium Abstract Book

RISE SPONSORED STUDENT SUMMER SYMPOSIUM Thursday August 24, 2017 Research Presenters: RISE, McNair, LSAMP Student Researchers Time: 8:30AM-3:30PM (Lunch Provided) Location: Bldg 4-2-314 (Conference Room) Presentation Schedule Introduction by Dr. Jill Adler Moderator: Dr. Jill Adler Time Name Presentation Title 8:30AM Tim Batz Morphological and developmental studies of the shoot apical meristem in Aquilegia coerulea 8:45 Uriah Sanders Analysis of gene expression in developing shoot apical meristems of Aquilegia coerulea 9:00 Summer Blanco Techniques to Understand Floral Organ Abscission in Delphinium Species 9:15 Sierra Lauman Restoration of invaded walnut woodlands using a trait-based community assembly approach 9:30 Eddie Banuelos Assessment of Titanium-based prosthetic alloy colonization by Staphylococcus epidermidis & Pseudomonas aeruginosa 9:45 Jacqueline Transformation efficiency and the effects of ampicillin on bacterial Gutierrez growth 10:00 Break Moderator: Dr. Nancy Buckley 10:15 Marie Gomez Building a quantitative model for studying the effect of antibiotics that inhibit protein translation in live cells 10:30 Taylor Halsey Monitoring changing levels of ghrelin and calcium using silica- encapsulated mammalian cells 10:45 Isis Janilkarn-Urena Comparing the effect of garlic and allicin between J774A.1 and RAW 264.7 murine macrophages in response to LPS and Heat Killed Candida albicans 11:00 Jacqueline Lara Small Cell Lung Cancer: the use of Aurora Kinase inhibitors and BCL2 inhibitors as alternative therapeutics 11:15 Jade Lolarga Validation of overexpression and knockdown of Twist1 in breast cancer cells 11:30 Ben Soto Construction of clinically relevant mutations in Ten-eleven translocation methylcytosine dioxygenase 2 (TET2) 11:45 Lunch Moderator: Dr. -

National Monuments and the Forest Service

NATIONAL MONUMENTS AND THE FOREST SERVICE Gerald W. Williams, Ph.D., (Retired) USDA Forest Service Washington, DC National monuments are areas of federal land set aside by the Congress or most often by the president, under authority of the American Antiquities Act of June 8, 1906, to protect or enhance prominent or important features of the national landscape. Such important national features include those land areas that have historic cultural importance (sites and landmarks), prehistoric prominence, or those of scientific or ecological significance. Today, depending on how one counts, there are 81 national monuments administered by the USDI National Park Service, 13 more administered by the USDI Bureau of Land Management (BLM), five others administered by the USDA Forest Service, two jointly managed by the BLM and the National Park Service, one jointly administered by the BLM and the Forest Service, one by the USDI Fish & Wildlife Service, and another by the Soldiers’ and Airmen’s Home in Washington, D.C. In addition, one national monument is under National Park Service jurisdiction, but managed by the Forest Service while another is on USDI Bureau of Reclamation administered land, but managed by the Park Service. The story of the national monuments and the Forest Service also needs to cover briefly the creation of national parks from national forest and BLM lands. More new national monuments and national parks are under consideration for establishment. ANTIQUITIES ACT OF 1906 Shortly after the turn of the century, many citizens’ groups and organizations, as well as members of Congress, believed it was necessary that an act of Congress be passed to combat the increasing acts of vandalism and even destruction of important cultural (historic and prehistoric), scenic, physical, animal, and plant areas around the country (Rothman 1989). -

December 2012 Number 1

Calochortiana December 2012 Number 1 December 2012 Number 1 CONTENTS Proceedings of the Fifth South- western Rare and Endangered Plant Conference Calochortiana, a new publication of the Utah Native Plant Society . 3 The Fifth Southwestern Rare and En- dangered Plant Conference, Salt Lake City, Utah, March 2009 . 3 Abstracts of presentations and posters not submitted for the proceedings . 4 Southwestern cienegas: Rare habitats for endangered wetland plants. Robert Sivinski . 17 A new look at ranking plant rarity for conservation purposes, with an em- phasis on the flora of the American Southwest. John R. Spence . 25 The contribution of Cedar Breaks Na- tional Monument to the conservation of vascular plant diversity in Utah. Walter Fertig and Douglas N. Rey- nolds . 35 Studying the seed bank dynamics of rare plants. Susan Meyer . 46 East meets west: Rare desert Alliums in Arizona. John L. Anderson . 56 Calochortus nuttallii (Sego lily), Spatial patterns of endemic plant spe- state flower of Utah. By Kaye cies of the Colorado Plateau. Crystal Thorne. Krause . 63 Continued on page 2 Copyright 2012 Utah Native Plant Society. All Rights Reserved. Utah Native Plant Society Utah Native Plant Society, PO Box 520041, Salt Lake Copyright 2012 Utah Native Plant Society. All Rights City, Utah, 84152-0041. www.unps.org Reserved. Calochortiana is a publication of the Utah Native Plant Society, a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organi- Editor: Walter Fertig ([email protected]), zation dedicated to conserving and promoting steward- Editorial Committee: Walter Fertig, Mindy Wheeler, ship of our native plants. Leila Shultz, and Susan Meyer CONTENTS, continued Biogeography of rare plants of the Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge, Nevada. -

Atlas of Rare Endemic Vascular Plants of the Arctic

Atlas of Rare Endemic Vascular Plants of the Arctic Technical Report No. 3 About CAFF Theprogram for the Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF) of the Arctic Council was established lo address the special needs of Arctic ecosystems, species and thcir habitats in the rapid ly developing Arctic region. Itwas initiated as one of'four programs of the Arctic Environmental Protcction Strategy (AEPS) which was adopted by Canada, Denmark/Greenland, Finland, lceland, Norway, Russia, Swcdcn and the United States through a Ministeria! Declaration at Rovaniemi, Finland in 1991. Other programs initi ated under the AEPS and overlaken hy the Are.tie Council are the ArcticMonitoring and assessment Programme (AMAP), the program for Emergency Prevention, Preparcd ness and Response (EPPR) and the program for Protection of the Arctic Marine Envi ronment (PAME). Sinceits inaugural mccti.ng in Ottawa, Canada in 1992, the CAFF program has provided scientists, conscrvation managers and groups, and indigenous people of the north with a distinct forum in which lo tackle a wide range of Arctic conservation issues at the cir cumpolar level. CAFF's main goals, which are achieved in keeping with the concepts of sustainable developrnertt and utilisation, are: • to conserve Arctic Jlora and fauna, thcir diversity and thcir habitats; • to protect the Arctic ecosystems from threats; • to improve conservation management laws, reg ulations and practices for the Arclic; • to integrale Arctic interests into global conservation fora. CAFF operates rhrough a system of Designated Agencies and National Representatives responsible for CAFF in thcir rcspcctivc countries. CAFF also has an International Work ing Group wh.ith has met annually to assess progrcss and to develop Annual WorkPlans. -

Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences (4)5

PROCEEDINGS OF THE CALIFORNIA Academy of Sciences FOURTH SERIES Vol. V 1915 OS" SAN P^RANCISCO PUBLISHED BY THE ACADEMY 1915 COMMITTEE ON PUBLICATION George C. Edwards, Chairman C. E. Grunsky Barton Warren Evermann, Editor CONTENTS OF VOLUME V. Plates 1-19. PAGE Title-page i Contents iii Report of the President of the Academy for the Year 1914. By C. E. Grunsky 1 (Published March 26, 1915) Report of the Director of the Museum for the Year 1914. By Barton Warren Evermann - 1 1 (Published March 26, 1915) Fauna of the Type Tejon : Its Relation to the Cowlitz Phase of the Tejon Group of Washington. By Roy E. Dickerson. (Plates 1-11) 33 (Published June 15, 1915) A List of the Amphibians and Reptiles of Utah, with Notes on the Species in the Collection of the Academy. By John Van Den- burgh and Joseph R. Slevin. (Plates 12-14) 99 (Published June 15, 1915) Description of a New Subgenus (Arborimus) of Phenacomys, with a Contribution to Knowledge of the Habits and Distribution of Phenacomys longicaudus True. By Walter P. Taylor. (Plate 15) 1 1 1 (Published December 30, 1915) Tertiary Deposits of Northeastern Mexico. By E. T. Durable. (Plates 16-19) 163 (Published December 31, 1915) Report of the President of the Academy for the Year 1915. By C. E. Grunsky 195 (Published May 4, 1916) Report of the Director of the Museum for the Year 1915. By Barton Warren Evermann 203 (Published May 4, 1916) Index 225, 232 July 19, 1916 / f / ^3 F»ROCEDEDINGS OF THE CALIFORNIA ACADEMY OF SCIENCES Fourth Series Vol.