Cuvier's Smooth-Fronted Caiman Paleosuchus Palpebrosus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caiman Crocodilus Fuscus

Facultad de Ciencias ACTA BIOLÓGICA COLOMBIANA Departamento de Biología http://www.revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/actabiol Sede Bogotá ARTÍCULO DE INVESTIGACIÓN / RESEARCH ARTICLE ZOOLOGIA DETERMINATION OF HEMATOLOGICAL VALUES OF COMMON CROCODILE (Caiman crocodilus fuscus) IN CAPTIVITY IN THE MAGDALENA MEDIO OF COLOMBIA Determinación de valores hematológicos de caimán común (Caiman crocodilus fuscus) en cautiverio en el Magdalena Medio de Colombia Juana GRIJALBA O1 , Elkin FORERO1 , Angie CONTRERAS1 , Julio VARGAS1 , Roy ANDRADE1 1Facultad de Ciencias Agropecuarias, Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia, Avenida Central del Norte 39-115, 150003 Tunja, Tunja, Boyacá, Colombia *For correspondence: [email protected] Received: 04th December 2018 , Returned for revision: 03rd March 2019, Accepted: 08th May 2019. Associate Editor: Nubia E. Matta. Citation/Citar este artículo como: Grijalba J, Forero E, Contreras A, Vargas J, Andrade R. Determination of hematological values of common crocodile (Caiman crocodilus fuscus) in captivity in the Magdalena Medio of Colombia. Acta biol. Colomb. 2020;25(1):75-81. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/ abc.v25n1.76045 ABSTRACT Caiman zoo breeding (Caiman crocodilus fuscus) has been developing with greater force in Colombia since the 90s. It is essential to evaluate the physiological ranges of the species to be able to assess those situations in which their health is threatened. The objective of the present study was to determine the typical hematological values of the Caiman (Caiman crocodilus fuscus) with the aid of the microhematocrit, the cyanmethemoglobin technique, and a hematological analyzer. The blood samples were taken from 120 young animals of both sexes in good health apparently (males 44 and females 76). -

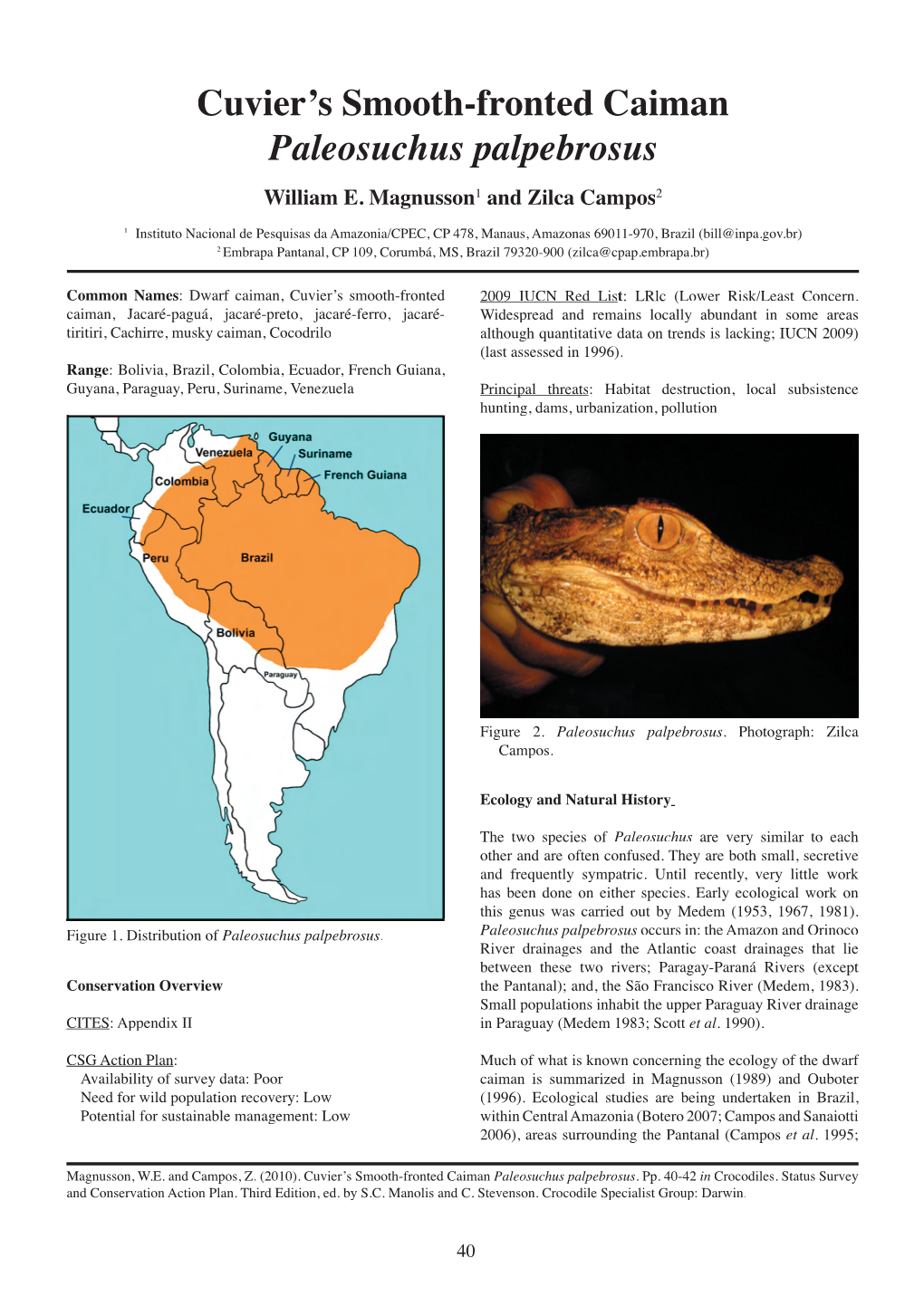

Schneider's Smooth-Fronted Caiman Paleosuchus Trigonatus

Schneider’s Smooth-fronted Caiman Paleosuchus trigonatus Zilca Campos1, William E. Magnusson2 and Fábio Muniz3 1Embrapa Pantanal, CP 109, Corumbá, MS, Brazil 79320-900 ([email protected]) 2Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazonia/CPEC, CP 478, Manaus, Amazonas 69011-970, Brazil ([email protected]) 3Laboratório de Evolução e Genética Animal, Universidade Federal do Amazonas, Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil ([email protected]) Common Names: Smooth-fronted caiman, Schneider’s 2018 IUCN Red List: Lower Risk/Least Concern. Widespread smooth-fronted caiman, Cachirre, Jacaré-coroa, Jacaré-curuá and remains locally abundant, although quantitative data are una lacking (last assessed in March 2018; Campos et al. 2019). Range: Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, French Guiana, Principal threats: Habitat destruction, local subsistence Guyana, Peru, Suriname, Venezuela hunting, pollution, urbanization, dams Figure 2. Paleosuchus trigonatus. Photograph: Zilca Campos. Ecology and Natural History Paleosuchus trigonatus has a maximum length of around 2.3 m (Medem 1952, 1981). It is well adapted to a terrestrial mode of life and in swift-running waters (Medem 1958). It has a similar distribution to P. palpebrosus, but does not enter the Brazilian shield region or the Paraguay River drainage. In Brazil P. trigonatus is found principally in the rivers and streams of heavily-forested habitats (Magnusson 1992; Villamarím et al. 2017), in igapó forest in the Central Amazon (Mazurek-Souza 2001), and open water or near Figure 1. Distribution of Paleosuchus trigonatus (based on waterfalls in the large rivers such as the Mamoré, Madeira, Campos et al. 2013, 2017). Abunã (Vasconcelos and Campos 2007) and Beni Rivers (Z. Campos, unpublished data). -

Vocalizations in Two Rare Crocodilian Species: a Comparative Analysis of Distress Calls of Tomistoma Schlegelii (Müller, 1838) and Gavialis Gangeticus (Gmelin, 1789)

NORTH-WESTERN JOURNAL OF ZOOLOGY 11 (1): 151-162 ©NwjZ, Oradea, Romania, 2015 Article No.: 141513 http://biozoojournals.ro/nwjz/index.html Vocalizations in two rare crocodilian species: A comparative analysis of distress calls of Tomistoma schlegelii (Müller, 1838) and Gavialis gangeticus (Gmelin, 1789) René BONKE1,*, Nikhil WHITAKER2, Dennis RÖDDER1 and Wolfgang BÖHME1 1. Herpetology Department, Zoologisches Forschungsmuseum Alexander Koenig (ZFMK), Adenauerallee 160, 53113 Bonn, Germany. 2. Madras Crocodile Bank Trust, P.O. Box 4, Mamallapuram, Tamil Nadu 603 104, S.India. *Corresponding author, R. Bonke, E-mail: [email protected] Received: 07. August 2013 / Accepted: 16. October 2014 / Available online: 17. January 2015 / Printed: June 2015 Abstract. We analysed 159 distress calls of five individuals of T. schlegelii for temporal parameters and ob- tained spectral parameters in 137 of these calls. Analyses of G. gangeticus were based on 39 distress calls of three individuals, of which all could be analysed for temporal and spectral parameters. Our results document differences in the call structure of both species. Distress calls of T. schlegelii show numerous harmonics, whereas extensive pulse trains are present in G. gangeticus. In the latter, longer call durations and longer in- tervals between calls resulted in lower call repetition rates. Dominant frequencies of T. schlegelii are higher than in G. gangeticus. T. schlegelii specimens showed a negative correlation of increasing body size with de- creasing dominant frequencies. Distress call durations increased with body size. T. schlegelii distress calls share only minor structural features with distress calls of G. gangeticus. Key words: Tomistoma schlegelii, Gavialis gangeticus, distress calls, temporal parameters, spectral parameters. -

Crocodiles and Alligators Capture Production by Species, Fishing Areas

394 Crocodiles and alligators Capture production by species, fishing areas and countries or areas B-73 Crocodiles et alligators Captures par espèces, zones de pêche et pays ou zones Cocodrilos y aligatores Capturas por especies, áreas de pesca y países o áreas Species, Fishing area Espèce, Zone de pêche 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 Especie, Área de pesca no no no no no no no no no no Broad-nosed caiman ...B ...C Caiman latirostris 5,36(01)001,01 IMO 03 Argentina - - - 90 165 215 2 752 1 652 1 125 705 Brazil - - - - - 10 ... 50 - - 03 Fishing area total - - - 90 165 225 2 752 1 702 1 125 705 Species total - - - 90 165 225 2 752 1 702 1 125 705 Spectacled caiman Caïman à lunettes Caimán de anteojos Caiman crocodilus 5,36(01)001,03 CAI 02 Nicaragua 250 6 440 ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 130 Panama 10 10 250 11 700 13 298 14 694 15 850 4 696 2 210 2 752 1 155 02 Fishing area total 260 16 690 11 700 13 298 14 694 15 850 4 696 2 210 2 752 1 285 03 Argentina - - - - - 1 1 291 2 883 6 083 3 556 Bolivia 17 500 ... 28 170 31 018 43 528 36 299 51 330 44 443 49 115 51 618 Brazil 4 619 8 286 1 253 6 048 12 851 7 004 620 673 10 254 ... Colombia 771 456 832 203 704 313 540 579 555 719 612 041 601 958 974 721 673 062 535 394 Guyana 9 880 9 880 5 917 8 222 3 124 3 310 2 301 3 720 16 707 3 355 Paraguay - 9 750 3 793 8 373 4 409 - - - - - Venezuela 24 640 23 655 19 215 20 349 33 942 63 902 58 346 60 864 23 201 15 489 03 Fishing area total 828 095 883 774 762 661 614 589 653 573 722 557 715 846 1 087 304 778 422 609 412 Species total -

CAIMAN CARE Thomas H

CAIMAN CARE Thomas H. Boyer, DVM, DABVP, Reptile and Amphibian Practice 9888-F Carmel Mountain Road, San Diego, CA, 92129 858-484-3490 www.pethospitalpq.com – www.facebook.com/pethospitalpq The spectacled caiman (Caiman crocodilus) is a popular animal among reptile enthusiasts. It is easy to understand their appeal, hatchlings are widely available outside California and make truly fascinating pets. Unfortuneately, if fed and housed properly they can grow a foot per year for the first few years and can rapidly outgrow their accommodations. Crocodilians are illegal in California without special permits. Most crocodilians are severely endangered (some are close to extinction) but spectacled caimans are one of the few species that aren't, therefore zoos are not interested in keeping them. Within a few years the endearing pet becomes a problem that nobody, including the owner, wants. They are difficult to give away. Some elect euthanasia at this point but most caimans die from inadequate care before they get big enough to become a problem. Other crocodilians are so severely endangered that it is illegal to own or trade in them, live or dead, without federal permits. Obviously I discourage individuals from purchasing an animal that within a few years will be an unsuitable pet. Although I can't endorse caimans as pets, I still feel if one has a caiman it should be cared for properly. One must realize that almost all crocodilians (the American Alligator is an exception) are tropical reptiles, thus they need a warm environment. Water temperature should be 75 to 80 F at all times. -

Phylogenetic Taphonomy: a Statistical and Phylogenetic

Drumheller and Brochu | 1 1 PHYLOGENETIC TAPHONOMY: A STATISTICAL AND PHYLOGENETIC 2 APPROACH FOR EXPLORING TAPHONOMIC PATTERNS IN THE FOSSIL 3 RECORD USING CROCODYLIANS 4 STEPHANIE K. DRUMHELLER1, CHRISTOPHER A. BROCHU2 5 1. Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, The University of Tennessee, Knoxville, 6 Tennessee, 37996, U.S.A. 7 2. Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, The University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa, 8 52242, U.S.A. 9 email: [email protected] 10 RRH: CROCODYLIAN BITE MARKS IN PHYLOGENETIC CONTEXT 11 LRH: DRUMHELLER AND BROCHU Drumheller and Brochu | 2 12 ABSTRACT 13 Actualistic observations form the basis of many taphonomic studies in paleontology. 14However, surveys limited by environment or taxon may not be applicable far beyond the bounds 15of the initial observations. Even when multiple studies exploring the potential variety within a 16taphonomic process exist, quantitative methods for comparing these datasets in order to identify 17larger scale patterns have been understudied. This research uses modern bite marks collected 18from 21 of the 23 generally recognized species of extant Crocodylia to explore statistical and 19phylogenetic methods of synthesizing taphonomic datasets. Bite marks were identified, and 20specimens were then coded for presence or absence of different mark morphotypes. Attempts to 21find statistical correlation between trace types, marking animal vital statistics, and sample 22collection protocol were unsuccessful. Mapping bite mark character states on a eusuchian 23phylogeny successfully predicted the presence of known diagnostic, bisected marks in extinct 24taxa. Predictions for clades that may have created multiple subscores, striated marks, and 25extensive crushing were also generated. Inclusion of fossil bite marks which have been positively 26associated with extinct species allow this method to be projected beyond the crown group. -

Identification Notes &~@~-/~: ~~*~@~,~ 'PTILE

CATEGORY Identification Notes &~@~-/~: ~~*~@~,~ ‘PTILE for wildlife law enforcement ~ C.rnrn.n N.rn./s: Al@~O~, c~~~dil., ~i~.xl, Gharial PROBLEM: Skulls of Crocodilians are often imported as souvenirs. nalch (-”W 4(JI -“by ieeth ??la&ularJy+i9 GUIDE TO PRELIMINARY IDENTIFICATION OF CROCODILL4N SKULLS 1. Nasal bones separated from nasal aperture; mandibular symphysis extends to the 15th tooth. 2. Gavialis gangeticus Nasal bones entering the nasal aperture; mandibular symphysisdoes not extend beyond the8th tooth . Tomistoma schlegelii 2. Nasal bones separated from premaxillary bones; 27 -29maxi11aryteeth,25 -26mandibularteeth Nasal bones in contact with premaxillaq bo Qoco@khs acutus teeth, 18-19 mandibular teeth . Tomiitomaschlegelii 3. Fourth mandibular tooth usually fitting into a notch in the maxilla~, 16-19 maxillary teeth, 14-15 mandibular teeth . .4 Osteolaemus temaspis Fourth mandibular tooth usually fitting into a pit in the maxilla~, 14-20 maxillary teeth, 17-22 mandibular teeth . .5 4. Nasal bones do not divide nasal aperture. .. CrocodylW (12 species) Alligator m&siss@piensh Nasalboncx divide nasal aperture . Osteolaemustetraspk. 5. Nasal bones do not divide nasal aperture. .6 . Paleosuchus mgonatus Bony septum divides nasal aperture . .. Alligator (2 species) 6. Fiveteethinpremaxilla~ bone . .7 . Melanosuchus niger Four teeth in premaxillary bone. ...Paleosuchus (2species) 7. Vomerexposed on the palate . Melanosuchusniger Caiman crocodiles Vomer not exposed on palate . ...”..Caiman (2species) Illustrations from: Moo~ C. C 1921 Me&m, F. 19S1 L-.. Submitted by: Stephen D. Busack, Chief, Morphology Section, National Fish& Wildlife Forensics LabDate submitted 6/3/91 Prepared in cooperation with the National Fkh & Wdlife Forensics Laboratoy, Ashlar@ OR, USA ‘—m More on reverse side>>> IDentMcation Notes CATEGORY: REPTILE for wildlife law enforcement -- Crocodylia II CAmmom Nda Alligator, Crocodile, Caiman, Gharial REFERENCES Medem, F. -

Growth Rates of Paleosuchus Palpebrosus at the Southern Limit of Its Range Author(S): Zilca Campos , William E

Growth Rates of Paleosuchus palpebrosus at the Southern Limit of its Range Author(s): Zilca Campos , William E. Magnusson , and Vanílio Marques Source: Herpetologica, 69(4):405-410. 2013. Published By: The Herpetologists' League DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1655/HERPETOLOGICA-D-13-00005 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1655/HERPETOLOGICA-D-13-00005 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/ terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Herpetologica, 69(4), 2013, 405–410 Ó 2013 by The Herpetologists’ League, Inc. GROWTH RATES OF PALEOSUCHUS PALPEBROSUS AT THE SOUTHERN LIMIT OF ITS RANGE 1,4 2 3 ZILCA CAMPOS ,WILLIAM E. MAGNUSSON , AND VANILIO´ MARQUES 1Laboratorio´ de vida selvagem, Embrapa Pantanal, CP 109, Corumba´, MS, 793200-900, Brazil 2Coordena¸ca˜o de Biodiversidade, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisa da Amazonia,ˆ CP 2223, Manaus, AM, 69080-971, Brazil 3Instituo Chico Mendes de Conserva¸ca˜o de Biodiversidade, CP 100, Cuiaba´, MT, 78055-900, Brazil ABSTRACT: We estimated growth rates of Dwarf Caiman (Paleosuchus palpebrosus) with capture– recapture data from 40 individuals collected over 6 yr in streams surrounding the Brazilian Pantanal, near the southern limit of the species’ distribution. -

Surveying Death Roll Behavior Across Crocodylia

Ethology Ecology & Evolution ISSN: 0394-9370 (Print) 1828-7131 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/teee20 Surveying death roll behavior across Crocodylia Stephanie K. Drumheller, James Darlington & Kent A. Vliet To cite this article: Stephanie K. Drumheller, James Darlington & Kent A. Vliet (2019): Surveying death roll behavior across Crocodylia, Ethology Ecology & Evolution, DOI: 10.1080/03949370.2019.1592231 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/03949370.2019.1592231 View supplementary material Published online: 15 Apr 2019. Submit your article to this journal View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=teee20 Ethology Ecology & Evolution, 2019 https://doi.org/10.1080/03949370.2019.1592231 Surveying death roll behavior across Crocodylia 1,* 2 3 STEPHANIE K. DRUMHELLER ,JAMES DARLINGTON and KENT A. VLIET 1Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, The University of Tennessee, 602 Strong Hall, 1621 Cumberland Avenue, Knoxville, TN 37996, USA 2The St. Augustine Alligator Farm Zoological Park, 999 Anastasia Boulevard, St. Augustine, FL 32080, USA 3Department of Biology, University of Florida, 208 Carr Hall, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA Received 11 December 2018, accepted 14 February 2019 The “death roll” is an iconic crocodylian behaviour, and yet it is documented in only a small number of species, all of which exhibit a generalist feeding ecology and skull ecomorphology. This has led to the interpretation that only generalist crocodylians can death roll, a pattern which has been used to inform studies of functional morphology and behaviour in the fossil record, especially regarding slender-snouted crocodylians and other taxa sharing this semi-aquatic ambush pre- dator body plan. -

Historical Biology Crocodilian Behaviour: a Window to Dinosaur

This article was downloaded by: [Watanabe, Myrna E.] On: 11 March 2011 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 934811404] Publisher Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Historical Biology Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713717695 Crocodilian behaviour: a window to dinosaur behaviour? Peter Brazaitisa; Myrna E. Watanabeb a Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, New Haven, CT, USA b Naugatuck Valley Community College, Waterbury, CT, USA Online publication date: 11 March 2011 To cite this Article Brazaitis, Peter and Watanabe, Myrna E.(2011) 'Crocodilian behaviour: a window to dinosaur behaviour?', Historical Biology, 23: 1, 73 — 90 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/08912963.2011.560723 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2011.560723 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

(Schneider, 1801) (Crocodylia: Alligatoridae), in the Amazon–Cerrado Transition, Brazil

13 4 91–94 Date 2017 NOTES ON GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION Check List 13 (4): 91–94 https://doi.org/10.15560/13.4.91 Extension of the geographical distribution of Schneider’s Dwarf Caiman, Paleosuchus trigonatus (Schneider, 1801) (Crocodylia: Alligatoridae), in the Amazon–Cerrado transition, Brazil Zilca Campos,1 Fábio Muniz,2 William E. Magnusson2 1 Embrapa Pantanal, CP 109, 79320-900 Corumbá, MS, Brazil. 2 Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia, CP 2223, 69080-971 Manaus, AM, Brazil. Corresponding author: Zilca Campos, [email protected] Abstract We present new records of occurrence of Schneider’s Dwarf Caiman, Paleosuchus trigonatus and extend its geo- graphical distribution. Eight individuals were caught in the following locations: Sangue River, in the municipality of Campo Novo dos Parecis, Claro River and Marapi River, in the municipality of São José do Rio Claro, and tributaries of the Juruena River, in the state of Mato Grosso, Brazil. These records extend the geographical distribution of the species nearly 500 km south of the limit given in published range maps. Key words New records; conservation; Paleosuchus; Mato Grosso; Brazilian Amazon. Academic editor: Raul F. D. Sales | Received 30 June 2016 | Accepted 10 April 2017 | Published 12 July 2017 Citation: Campos Z, Muniz F, Magnusson WE (2017) Extension of the geographical distribution of Schneider’s Dwarf Caiman, Paleosuchus trigonatus (Schneider, 1801) (Crocodylia: Alligatoridae), in the Amazon-Cerrado transition, Brazil. Check List 13 (4): 91–94. https://doi. org/10.15560/13.4.91 Introduction known geographical distribution of P. trigonatus. These are the first occurrence records of the species in the Cer- The geographical distribution of Schneider’s Dwarf Cai- rado biome although still in the Amazon drainage. -

Cardiovascular Dynamics in Crocodylus Porosus Breathing Air and During Voluntary Aerobic Dives Gordon C

Cardiovascular dynamics in Crocodylus porosus breathing air and during voluntary aerobic dives Gordon C. Griggl and Kjell Johansen2 1 Zoology A.08, The University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia (since 1989: School of Integrative Biology, The University of Queensland, Brisbane , Australia) 2 Department of Zoophysiology, University of Aarhus, Aarhus DK-8000, Denmark Accepted December 1, 1986 Summary. Pressure records from the heart and outflow vessels of the heart of Crocodylus porosus resolve previously conflicting results, showing that left aortic filling via the foramen of Panizza may occur during both cardiac diastole and systole. Filling of the left aorta during diastole, identified by the asynchrony and comparative shape of pressure events in the left and right aortae, is reconciled more easily with the anatomy, which suggests that the foramen would be occluded by opening of the pocket valves at the base of the right aorta during systole. Filling during systole, indicated when pressure traces in the left and right aortae could be superimposed, was associated with lower systemic pressures, which may occur at the end of a voluntary aerobic dive or can be induced by lowering water temperature or during a long forced dive. To explain this flexibility, we propose that the foramen of Panizza is of variable calibre. The presence of a 'right-left' shunt, in which increased right ventricular pressure leads to blood being diverted from the lungs and exiting the right ventricle via the left aorta, was found to be a frequent though not obligate correlate of voluntary aerobic dives. This contrasts with the previous concept of the shunt as a correlate of diving bradycardia.