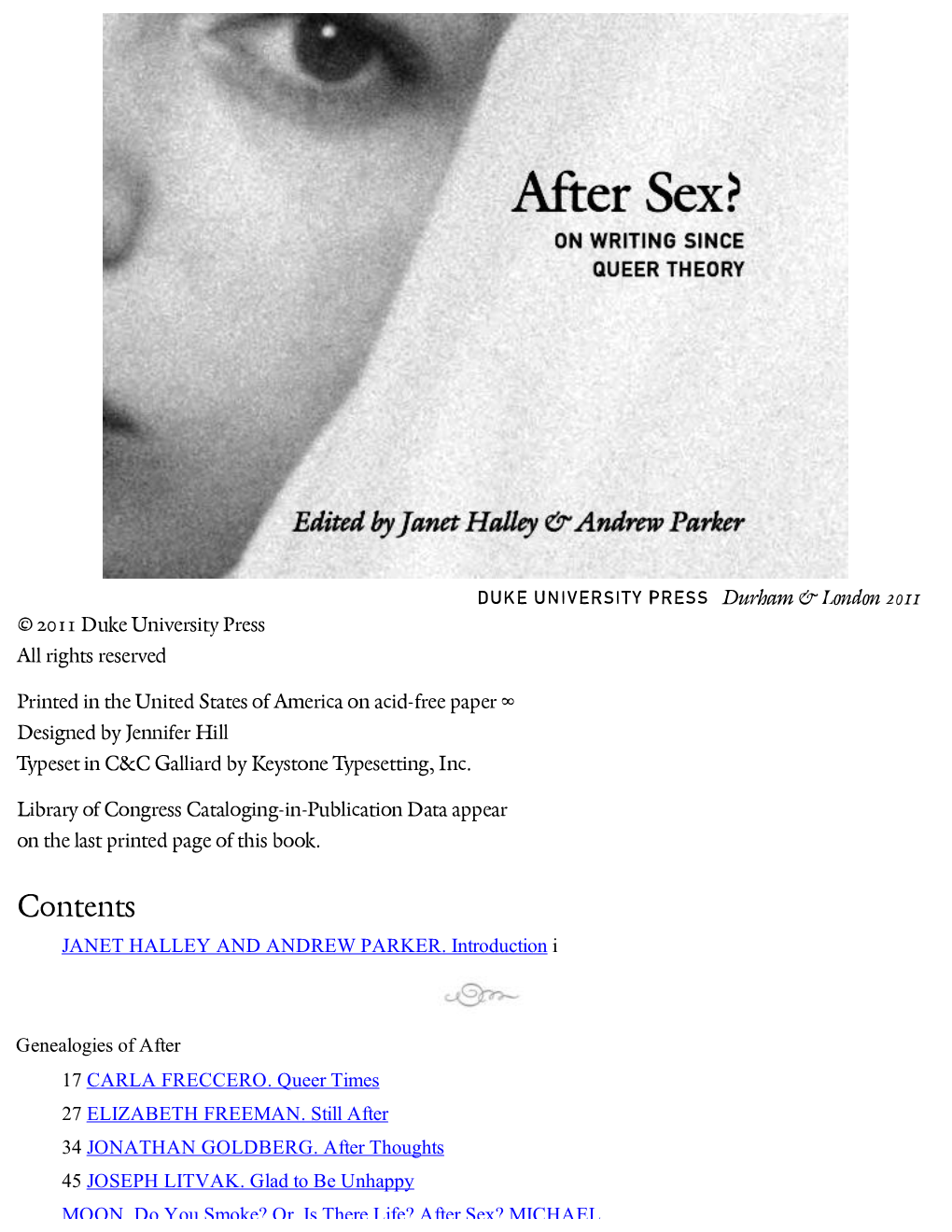

After Sex__ on Writing Since Queer Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December 2013 Michael Moon Graduate Institute of the Liberal Arts

December 2013 Michael Moon Graduate Institute of the Liberal Arts S-414 Callaway Center Emory University Atlanta GA 30322 [email protected] Positions Held Professor of English, Emory University, January 2013 to present. Professor of Women’s, Gender & Sexuality Studies, Emory University, July 2012 to present. Professor, Department of English, Johns Hopkins University, July 1998 to June 2006. Professor, Department of English, Duke University, July 1997 to June 1998. Associate Professor, Department of English, Duke University, July 1992 to June 1997. Assistant Professor, Department of English, Duke University, January 1989 to June 1992. Andrew W. Mellon Instructor, English, Duke University, 1987-88. Instructor, Department of English, Johns Hopkins University, 1985-87. Teaching Assistant, American Literature, Johns Hopkins University, Fall 1984. Education Ph.D. in English and American Literature, Johns Hopkins University, December 1988. Dissertation: "Whitman in Revision: The Politics of Corporeality and Textuality in the First Four Editions of Leaves of Grass." Directed by Professor Sharon Cameron. M.A. in English, The Johns Hopkins University, June 1985. B.A. magna cum laude, School of General Studies, Columbia University, January 1979. Awards and Honors Research Fellowship, Fox Center for Humanistic Inquiry, Emory University, September 2013-May 2014. Research Fellowship, Center for Critical Analysis of Contemporary Culture, Rutgers University, September 1994-May 1995. Recipient of ACLS Fellowship for Recent Recipients of the Ph.D, September 1989-May 1990. "Best Special Issue of 1989" Award of the Conference of Editors of Learned Journals presented South Atlantic Quarterly Special Issue on "Displacing Homophobia," co-edited by Michael Moon, Ronald R. Butters, and John M. -

Jews, the Blacklist, and Stoolpigeon Culture / Joseph Litvak

The Un-Americans Edited by Michèle Aina Barale Jonathan Goldberg Michael Moon Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick JOSEPH LITVAK The Un-Americans JEWS, THE BLACKLIST, AND STOOLPIGEON CULTURE Duke University Press Durham and London 2009 © 2009 Duke University Press All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper b Designed by C. H. Westmoreland Typeset in Scala with Gill Sans display by Achorn International, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Litvak, Joseph. The un-Americans : Jews, the blacklist, and stoolpigeon culture / Joseph Litvak. p. cm. — (Series Q) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-8223-4467-4 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn 978-0-8223-4484-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Jews in the motion picture industry—United States. 2. Jews—United States—Politics and government—20th century. 3. Antisemitism—United States—History—20th century. 4. United States—Ethnic relations—Political aspects. I. Title. II. Series: Series Q. e184.36.p64l58 2009 305.892’407309045—dc22 2009029295 TO LEE CONTENTS acknowledgments ix ❨1❩ Sycoanalysis: An Introduction 1 ❨2❩ Jew Envy 50 ❨3❩ Petrified Laughter: Jews in Pictures, 1947 72 ❨4❩ Collaborators: Schulberg, Kazan, and A Face in the Crowd 105 ❨5❩ Comicosmopolitanism: Behind Television 153 ❨6❩ Bringing Down the House: The Blacklist Musical 182 coda Cosmopolitan States 223 notes 229 bibliography 271 index 283 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This book is about, among other things, the thrill of naming names. As I look back on the process of writing it, it gives me great pleasure to point my finger at the accomplices who made it possible: Cheryl Alison, Susan Bell, Lauren Berlant, Susan David Bernstein, Diana Fuss, Jane Gallop, Marjorie Garber, Helena Gurfinkel, Judith Halberstam, Janet Halley, Jon- athan Gil Harris, Sonia Hofkosh, Carol Mavor, Meredith McGill, David McWhirter, Madhavi Menon, D. -

Ostridge Poster R3

63 RD SESSION Harvard University, Thompson Room, Barker Center, 12 Quincy Street • Friday, September 10 – Sunday, September 12, 2004 The English Institute SPONSORS 2004 Amherst College University of Arizona Baylor University Boston College Boston University Brandeis University Brigham Young University Brown University Bryn Mawr College University of California, Berkeley University of California, Riverside City College, CUNY Colgate University Columbia University Cornell University Dartmouth College Duke University Emory University Fordham University Georgetown University Harvard University Haverford College Ithaca College Johns Hopkins University Kent State University University of Michigan New York University University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill Northeastern University University of Notre Dame Ohio State University Pennsylvania State University University of Pennsylvania University of Pittsburgh Princeton University Rice University Rutgers University Saint Louis University Simmons College Smith College Stanford University Temple University Texas A&M University Trinity College Tufts University Vanderbilt University University of Washington Williams College University of Wisconsin, Madison Serial Dickens Yale University Directed by Directed by Pre-registration is strongly encouraged, as MICHAEL MOON, Johns Hopkins University CAROLYN WILLIAMS, Rutgers University seating is limited. Sign-in begins at 9 AM each morning. Registered conference participants are BRENT EDWARDS, Rutgers University ROSEMARIE BODENHEIMER, Boston College invited -

After Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick

come as you are after eve kosofsky sedgwick Before you start to read this book, take this moment to think about making a donation to punctum books, an independent non-profit press, @ https://punctumbooks.com/support/ If you’re reading the e-book, you can click on the image below to go directly to our donations site. Any amount, no matter the size, is appreciated and will help us to keep our ship of fools afloat. Contri- butions from dedicated readers will also help us to keep our commons open and to cultivate new work that can’t find a welcoming port elsewhere. Our ad- venture is not possible without your support. Vive la Open Access. Fig. 1. Hieronymus Bosch, Ship of Fools (1490–1500) come as you are. Copyright © 2021 by Jonathan Goldberg. after eve kosof- sky sedgwick. Copyright © 1999 by Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick. This work carries a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license, which means that you are free to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format, and you may also remix, transform and build upon the material, as long as you clearly attribute the work to the authors (but not in a way that suggests the authors or punctum books endorses you and your work), you do not use this work for commercial gain in any form whatsoever, and that for any remixing and trans- formation, you distribute your rebuild under the same license. http://creative- commons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ First published in 2021 by dead letter office, babel Working Group, an imprint of punctum books, Earth, Milky Way.