Rocky Mountain Wolf Recovery 1999 Annual Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memoirs of the Queensland Museum | Culture

Memoirs of the Queensland Museum | Culture Volume 7 Part 1 The Leichhardt diaries Early travels in Australia during 1842-1844 Edited by Thomas A. Darragh and Roderick J. Fensham © Queensland Museum PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone: +61 (0) 7 3840 7555 Fax: +61 (0) 7 3846 1226 Web: qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 1440-4788 NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the Editor in Chief. A Guide to Authors is displayed on the Queensland Museum website qm.qld.gov.au A Queensland Government Project 30 June 2013 The Leichhardt diaries. Early travels in Australia during 1842–1844 Diary No 2 28 December - 24 July 1843 (Hunter River - Liverpool Plains - Gwydir Des bords du Tanaïs au sommet du Cédar. - Darling Downs - Moreton Bay) Sur le bronze et le marbre et sur le sein des [Inside the front cover are two newspaper braves cuttings of poetry, The Lost Ship and The Et jusque dans le cœur de ces troupeaux Neglected Wife. Also there are manuscript d’esclaves stanzas of three pieces of poetry. The first Qu’il foulait tremblans sous son char. in German, the second in English from Jacob Faithful by Frederick Maryatt, and the third [On a reef lashed by the plaintive wave in French.] the navigator from afar sees whitening on the shore Die Gestalt, die die erste Liebe geweckt a tomb near the edge, dumped by the Vergisst sich nie billows; Um den grünsten Fleck in der Wüste der time has not yet darkened the narrow Zeit stone Schwebt zögernd sie and beneath the green fabric of the briar From the German poem of an English and of the ivy lady. -

Department of the Interior

Vol. 78 Thursday, No. 114 June 13, 2013 Part II Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 17 Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Removing the Gray Wolf (Canis lupus) From the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Maintaining Protections for the Mexican Wolf (Canis lupus baileyi ) by Listing It as Endangered; Proposed Revision to the Nonessential Experimental Population of the Mexican Wolf; Proposed Rules VerDate Mar<15>2010 17:54 Jun 12, 2013 Jkt 229001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4717 Sfmt 4717 E:\FR\FM\13JNP2.SGM 13JNP2 tkelley on DSK3SPTVN1PROD with PROPOSALS2 35664 Federal Register / Vol. 78, No. 114 / Thursday, June 13, 2013 / Proposed Rules DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR proposed rule also constitutes the Management; U.S. Fish and Wildlife completion of a status review for gray Service; 4401 N. Fairfax Drive, MS Fish and Wildlife Service wolves in the Pacific Northwest 2042–PDM; Arlington, Virginia 22203. initiated on May 5, 2011. We will post all comments on http:// 50 CFR Part 17 Finally, this proposed rule replaces www.regulations.gov. This generally [Docket No. FWS–HQ–ES–2013–0073; our May 5, 2011, proposed action to means that we will post any personal FXES11130900000C2–134–FF09E32000] remove protections for C. lupus in all or information you provide us (see the portions of 29 eastern states (76 FR RIN 1018–AY00 Public Comments section below for 26086). more information). Submissions of hard Endangered and Threatened Wildlife DATES: Comment submission: We will copy comments on our Proposed and Plants; Removing the Gray Wolf accept comments received or Revision to the Nonessential (Canis lupus) From the List of postmarked on or before September 11, Experimental Population of the Mexican Endangered and Threatened Wildlife 2013. -

An Independent Newspaper for the Pacific Northwest AUGUST 1997 VOL

An Independent Newspaper for the Pacific Northwest AUGUST 1997 VOL. 3 No. 3 Dear Reader early all the problems we face in Cascadia boil down to population. NAs Alan Durning and Christopher Crowther point out in their new book, Misplaced Blame: The Real Roots of Population Growth, the Pacific Northwest is growing nearly twice the North American rate and almost 50 percent faster than the global population. The Northwest population reached 15 million EDITORIAL in mid-1997 and is swelling by another 1 million every 40 months. Starting this month, with our cover story on growth pressures in the scenic Columbia River Gorge, Cascadia Times Boom Times The UnbearableRightness ot Breen will publish an occasional series on, Can the Columbia River Gorge survive the Life on the fault line of environmentally growth, growth management strategies demand for development? and what it all means. As senior editor correct energy Kathie Durbin reports from the Columbia by Kathie Durbin Page 9 Gorge, local politics threaten this national by Kevin Bell Page 7 treasure. This is true everywhere, because growth and land-use decisions are in varyingdegrees made at the local THE USUAL STUFF level. We aren't saying that local commu• FIELD NOTES: Green groups clash over Sierra REALITY CHECK: 16 nities cannot do a good job protecting places such as the Gorge, Snoqualmie logging. EPA fines big Alaska mine. toxic waste POINT OF VIEW: The ASARCO juggernaut and Pass, Whidbey Island, Lake Tahoe or the on crops. Oregon slams nuclear weapons plan 3 Muir Woods, to name just a few places of its proposed Rock Creek Mine. -

Porphyry and Other Molybdenum Deposits of Idaho and Montana

Porphyry and Other Molybdenum Deposits of Idaho and Montana Joseph E. Worthington Idaho Geological Survey University of Idaho Technical Report 07-3 Moscow, Idaho ISBN 1-55765-515-4 CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................ 1 Molybdenum Vein Deposits ...................................................................... 2 Tertiary Molybdenum Deposits ................................................................. 2 Little Falls—1 ............................................................................. 3 CUMO—2 .................................................................................. 3 Red Mountain Prospect—45 ...................................................... 3 Rocky Bar District—43 .............................................................. 3 West Eight Mile—37 .................................................................. 3 Devil’s Creek Prospect—46 ....................................................... 3 Walton—8 .................................................................................. 4 Ima—3 ........................................................................................ 4 Liver Peak (a.k.a. Goat Creek)—4 ............................................. 4 Bald Butte—5 ............................................................................. 5 Big Ben—6 ................................................................................. 6 Emigrant Gulch—7 ................................................................... -

Montana Forest Insect and Disease Conditions and Program Highlights

R1-16-17 03/20/2016 Forest Service Northern Region Montata Department of Natural Resources and Conservation Forestry Division In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992. Submit your completed form or letter to USDA by: (1) mail: U.S. -

High Mountain Lake Research Natural Areas in Idaho

102 103 Little Granite Creek Lakes (W ellner 1979). The natural area spans elevations from abou 427 m (1400 feet)where Little Granite Creek flows into the Little Granite Creek Research Natural Area Snake River to 2863 m (9393 ft) at the summit of one of the Nezperce National Forest peaks. The proposed RNA will contain the entire drainage o Little Granite Creek except for some recreational exclusions. There are five lakes and five ponds in the proposed RNA. Norm Howse surveyed Echo Lake, Quad Lake, and He Devil Lake on August 7-11, 1967 (Howse 1967). Fred Rabe and Nancy Savage subsequently made observations of Baldy Lake and Ponds 1-3 on September 27-29, 1974. Triangle Lake was not sampled. Location The high lakes in the proposed RNAare located in two basins forming the headwaters of Little Granite Creek in the Hells Canyon National Recreation Area. Ecoregion Section: BLUE MOUNTAINS (M332G), Idaho County; USGS Quad: HE DEVIL, SQUIRREL PR A I R I E From Riggins, Idaho, drive south about two miles to the Seven Devils Road (FR 517) and travel to Heaven’s Gate and the Seven Devil’s Guard Station. By trail, Quad Lake, He Devil Lake and Echo Lake are about 9 miles from the guard Station. View west of Seven Devils Mountain Range Classification Pond 5 Quad Lake • Subalpine, small, deep, cirque-scour lake • Low production potential Pond 4 • Circumneutral water in a basalt-granite basin • Inlet: none; Outlet: intermittent Pond 2 Echo Lake Pond 3 • Subalpine, small, deep, cirque-scour lake Pond 1 • Low production potential • Circumneutral water in a basalt-granite basin • Inlets: seeps; Outlet: 1 stream He Devil Lake • Subalpine, small, deep, cirque-scour lake • Medium production potential Geology • Circumneutral water in a basalt-granite basin • Inlet: none; Outlet: intermittent stream The area in the Seven Devisl Mountain Range is rich in aquat- ic features, ranging from cirque lakes and ponds to moderate to steep gradient streams. -

PETITION to PROTECT the HUMBOLDT MARTEN (Martes Caurina Humboldtensis) UNDER OREGON’S ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT

Attachment 2 PETITION TO PROTECT THE HUMBOLDT MARTEN (Martes caurina humboldtensis) UNDER OREGON’S ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT Photo © Charlotte Eriksson Oregon State University June 26, 2018 PETITIONERS Cascadia Wildlands is a non‐profit, public interest environmental organization headquartered in Eugene, Oregon. Cascadia Wildlands educates, agitates, and inspires a movement to protect and restore Cascadia’s wild ecosystems, including the species therein. We envision vast old‐growth forests, rivers full of wild salmon, wolves howling in the backcountry, and vibrant communities sustained by the unique landscapes of the Cascadia bioregion. We have worked for over a decade on Pacific marten issues in the Pacific Northwest. The Center for Biological Diversity is a non‐profit conservation organization with more than 1 million members and supporters dedicated to the conservation of endangered species and wild places, including members throughout the Pacific Northwest. The Center has been working to protect the Humboldt marten and its habitat for more than a decade. Defenders of Wildlife is a national non‐profit conservation organization founded in 1947 to protect all native animals and plants in their natural communities. Defenders works on mesocarnivore conservation and habitat connectivity in the range of the Humboldt marten through our field offices in Oregon and California. Environmental Protection Information Center is a community based, non‐profit organization that advocates for science‐based protection and restoration of Northwest California’s Forests. EPIC was founded in 1977 when local residents came together to successfully end aerial applications of herbicides by industrial logging companies in Humboldt County. Klamath‐Siskiyou Wildlands Center is a non‐profit, public interest organization that protects and restores wild nature in the Klamath‐Siskiyou region of northern California and southern Oregon. -

Jackson Hole Vacation Planner Vacation Hole Jackson Guide’S Guide Guide’S Globe Addition Guide Guide’S Guide’S Guide Guide’S

TTypefypefaceace “Skirt” “Skirt” lightlight w weighteight GlobeGlobe Addition Addition Book Spine Book Spine Guide’s Guide’s Guide’s Guide Guide’s Guide Guide Guide Guide’sGuide’s GuideGuide™™ Jackson Hole Vacation Planner Jackson Hole Vacation2016 Planner EDITION 2016 EDITION Typeface “Skirt” light weight Globe Addition Book Spine Guide’s Guide’s Guide Guide Guide’s Guide™ Jackson Hole Vacation Planner 2016 EDITION Welcome! Jackson Hole was recognized as an outdoor paradise by the native Americans that first explored the area thousands of years before the first white mountain men stumbled upon the valley. These lucky first inhabitants were here to hunt, fish, trap and explore the rugged terrain and enjoy the abundance of natural resources. As the early white explorers trapped, hunted and mapped the region, it didn’t take long before word got out and tourism in Jackson Hole was born. Urbanites from the eastern cities made their way to this remote corner of northwest Wyoming to enjoy the impressive vistas and bounty of fish and game in the name of sport. These travelers needed guides to the area and the first trappers stepped in to fill the niche. Over time dude ranches were built to house and feed the guests in addition to roads, trails and passes through the mountains. With time newer outdoor pursuits were being realized including rafting, climbing and skiing. Today Jackson Hole is home to two of the world’s most famous national parks, world class skiing, hiking, fishing, climbing, horseback riding, snowmobiling and wildlife viewing all in a place that has been carefully protected allowing guests today to enjoy the abundance experienced by the earliest explorers. -

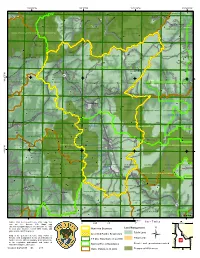

High Resolution Adobe PDF

115°20'0"W 115°0'0"W 114°40'0"W 114°20'0"W PISTOL LAKE " CHINOOK MOUNTAIN ARTILLERY DOME SLIDEROCK RIDGE FALCONBERRY PEAK ROCK CREEK SHELDON PEAK Red Butte "Grouse Creek Peak WHITE GOAWTh iMte OVaUlleNyT MAoIuNntain LITTLE SOLDIER MOUNTAIN N FD " N FD 6 8 8 T d Parker Mountain 6 Greyhound Mountain r R a k i e " " 5 2 l e 0 1 0 r 0 0 il 1 C l i a 1 n r o Big Soldier Mountain a o e pi r n Morehead Mountain T Pinyon Peak L White MoSunletain g Deer Rd " T " HONEYMOON LAKE " " BIG SOLDIER MOUNTAIN SOLDIER CREEK GREYHOUND MOUNTAIN PINYON PEAK CASTO SHERMAN PEAK CHALLIS CREEK LAKES TWIN PEAKS PATS CREEK Lo FRANK CHURCH - RIVER OF NO RETURN WILDERNESS o n Sherman Peak C Mayfield Peak Corkscrew Mountain r " d e " " R ek ls R l d a Mosquito Flat Reservoir F r e Langer Peak rl g T g k a Ruffneck Peak " ac d D P R d " k R Blue Bunch Mo"untain d e M e k R ill C r e Bear Valley Mountain k e e htmile r " e ig C r E C en r C re d ave Estes Mountain e G ar B e k " R BLUE BUNCH MOUNTAIN d CAPE HORN LAKES LANGER PEAK KNAPP LAKES MOUNT JORDAN l Forest CUSTER ELEVENMILE CREEK BAYHORRSaEm sLhAorKn EMountaiBn AYHORSE Nat De Rd Keysto"ne Mountain velop Road 579 d R " Cabin Creek Peak Red Mountain rk Cape Horn MounCtaaipne Horn Lake #1 o Bay d " Bald Mountain F hors R " " e e Cr 2 d e eek 8 R " nk Rd 5 in Ya d a a nt o ou Lucky B R S A L M O N - C H A L L I S N Fo S p M y o 1 C d Bachelor Mountain R q l " u e 2 5 a e d v y 19 p R Bonanza Peak a B"ald Mountain e d e w Nf 045 D w R R N t " s H s H C d " e sf r e o Basin Butte r 0 t U ' o r e F a n e 0 l t 21 t -

Wolf and Elk Management in a Spatial Predator-Prey Ecosystem

Wolf and Elk Management in a Spatial Predator-Prey Ecosystem David Aadland David Finnoff Jacob Hochard Charles Sims* July 11, 2016 Abstract. This paper provides insights into a complex and politically charged wildlife management problem using a spatial predator-prey model. The model is motivated by the spatiotemporal dynamics between elk, wolves, hunters and cattle ranchers in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE). Wildlife managers set hunting rates for elk and wolves to maximize the stream of ecosystem services derived from the GYE over time. The management component of the model considers tradeoffs between tourism, hunting, and cattle grazing currently facing wildlife managers. The predator-prey component of the model incorporates intraspecific competition and spatially explicit predation risk calibrated to the GYE. Contrary to a recent judicial ruling that has placed a moratorium on hunting wolves in Wyoming, optimal management within our model calls for more aggressive wolf hunting outside of Yellowstone National Park (YNP). The model also calls for a lower elk hunting rate, which leads to a higher steady-state population of elk, more prey for wolves, and less livestock predation. This combination of a prescribed lower elk hunting rate and higher wolf hunting rate is robust to a wide range of parameter values. *Aadland ([email protected]) and Finnoff are associate professors in the Department of Economics and Finance, 1000 E. University Avenue, Laramie, WY 82071. Hochard is an assistant professor in the Department of Economics, East Carolina University. Sims is an assistant professor in the Department of Economics, University of Tennessee. 1 “The wolf’s repopulation of the northern parts of the lower forty-eight states, now well under way, will stand as one of the primary conservation achievements of the twentieth century…If we have learned anything from this ordeal, it is that the best way to ensure continued wolf survival is, ironically enough, not to protect wolves completely.” L. -

Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences in Montana

Report of Investigation 23 Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences in Montana Richard B. Berg 2015 Cover photo by Richard Berg. Sapphires (very pale green and colorless) concentrated by panning. The small red grains are garnets, commonly found with sapphires in western Montana, and the black sand is mainly magnetite. Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences, RI 23 Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences in Montana Richard B. Berg Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology MBMG Report of Investigation 23 2015 i Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences, RI 23 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................1 Descriptions of Occurrences ..................................................................................................7 Selected Bibliography of Articles on Montana Sapphires ................................................... 75 General Montana ............................................................................................................75 Yogo ................................................................................................................................ 75 Southwestern Montana Alluvial Deposits........................................................................ 76 Specifi cally Rock Creek sapphire district ........................................................................ 76 Specifi cally Dry Cottonwood Creek deposit and the Butte area .................................... -

Ultimate Western Swing Page 2 of 44 Trip Summary

Ultimate Western Swing Page 2 of 44 Trip Summary Day 1 Daily Overview Drive: Los Angeles, CA to Springdale, UT (450 Miles) Welcome to Springdale, Utah Day 2 Daily Overview Welcome to Zion National Park - Zion National Park ACTIVITY: Guided Half-Day Hike of The Narrows - The Narrows, Zion Narrows Tour Note: Confirm late check-out of RV Resort for tomorrow’s excursion (request 1:00 PM check-out time if possible). Day 3 Daily Overview Activity: Sandstone Slot Canyoneering Trip (guided) Drive: Springdale to Bryce Canyon Day 4 Daily Overview Acrivity: Explore Bryce Canyon Day 5 Daily Overview Drive: Bryce to Jackson, WY Welcome to Jackson Hole, Wyoming! - Jackson Hole Day 6 Daily Overview Getting around Jackson Hole and Grand Teton National Park - Jackson Hole Explore Grand Teton National Park - Teton National Forest Page 3 of 44 Day 7 Daily Overview Depart: Jackson to Cody Through Yellowstone (177 Miles) Welcome to Yellowstone National Park! - Yellowstone Park Service Stations, Service Stations Explore the Lewis River Canyon Area - Lewis Falls, Lewis Lake Explore West Thumb, Bridge Bay, Lake Yellowstone, and Hayden Valley Day 8 Daily Overview Welcome to Cody, Wyoming! Activity: Explore Cody Day 9 Daily Overview Drive: Cody to Sage Lodge - Through Cooke City (166 Miles) - Cooke City-Silver Gate, Albright Visitor Center, Sage Lodge Explore Lamar Valley and the Tower-Roosevelt Area. Explore the Mammoth Hot Springs Area. Welcome to Gardiner! - Gardiner Check in at Sage Lodge Day 10 Daily Overview Horseback riding and rafting in Paradise Valley