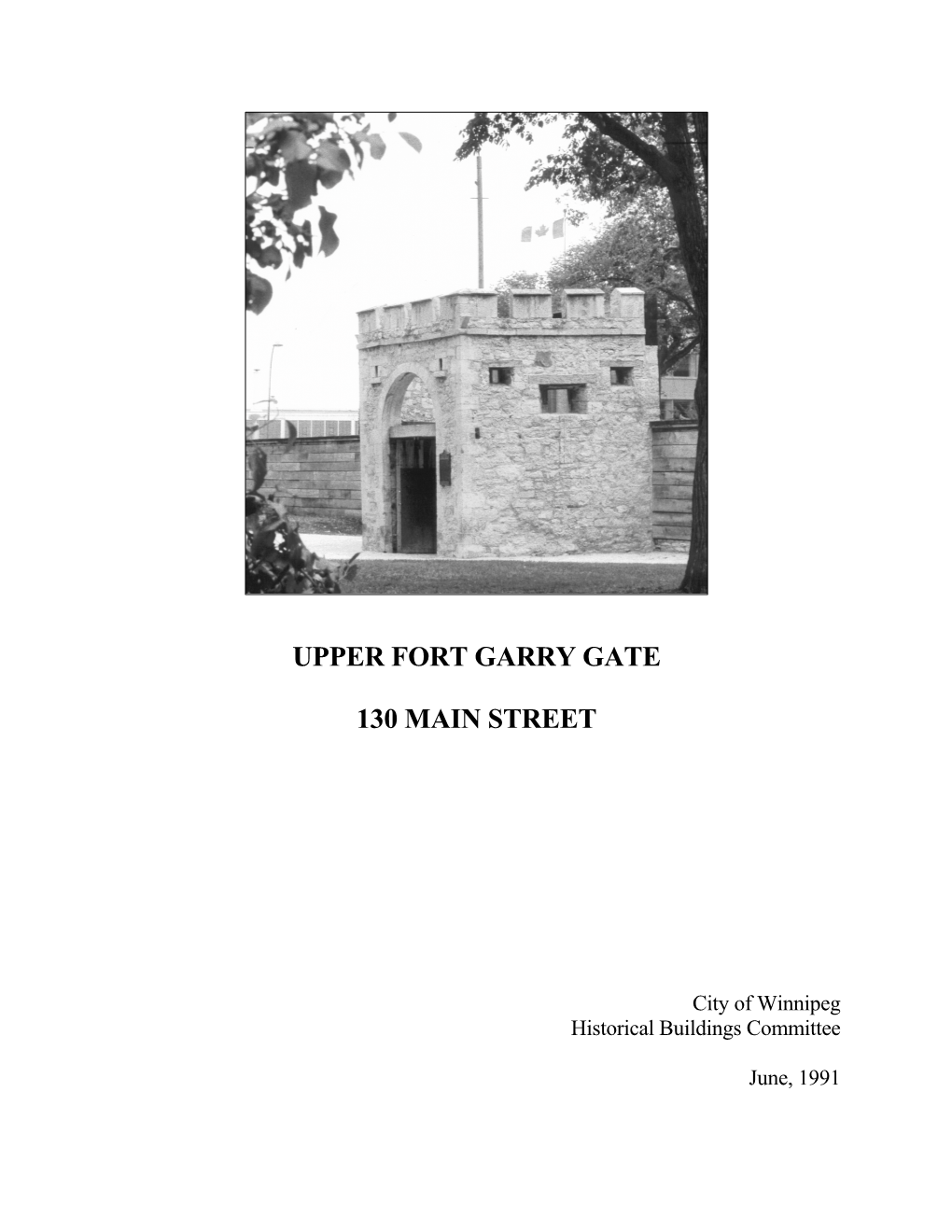

Upper Fort Garry Gate, 130 Main Street

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

October 2007

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Parks Canada The Forks National Historic Site of Canada : management plan / Parks Canada. Text in English and French on inverted pages. Title on added t.p.: Lieu historique national du Canada de la Fourche : plan directeur. ISBN 978-0-662-49889-6 Cat. no.: R64-105/71-2007 1. Forks National Historic Site, The (Winnipeg, Man.)--Management. 2. Historic sites--Canada--Management. 3. Historic sites--Manitoba--Management. 4. National parks and reserves--Canada--Management. 5. National parks and reserves--Manitoba--Management. I. Title. II. Title: Lieu historique national du Canada de la Fourche : plan directeur. FC3364F67P37 2007 971.27’43 C2007-980056-4E © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Chief Executive Officer of Parks Canada, 2007 The Forks NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE OF CANADA Management Plan October 2007 i Foreword Canada’s national historic sites, national parks and national marine conservation areas offer Canadians from coast-to-coast-to-coast unique opportunities to experience and understand our wonderful country. They are places of learning, recreation and fun where Canadians can connect with our past and appreciate the natural, cultural and social forces that shaped Canada. From our smallest national park to our most visited national historic site to our largest national marine conservation area, each of these places offers Canadians and visitors unique opportuni- ties to experience Canada. These places of beauty, wonder and learning are valued by Canadians - they are part of our past, our present and our future. Our Government’s goal is to ensure that each of these special places is conserved. -

Canadian Flag Collection Our Unique Exhibit Showcases Truly Canadian Businesses, Organizations and Historic Flags

Canadian Flag Collection Our unique exhibit showcases truly Canadian businesses, organizations and historic flags. We hold the nation’s second largest museum collection of Canadian flags! Why flags? Flags are all around us, we see them everyday. Canadians use flags to advertise, promote our organizations and rally behind for sporting events and national holidays. Our museum’s collection reflects this vital part of Canadian culture and daily life. We are proud to be the Argyle Homecoming Parade 2000 custodians of such important Canadian symbols as they continue to grow historically valuable with care and the passage of time. Our Collection: With over 815 flags, and growing everyday, our Canadian Regions & Cities collection is comprised of five galleries: Historical & Canadiana Sports & Organizations Canadian Business Commemorative & special Flags Flags in the media As our collection grows, so does it’s fame! We have received media coverage from: Winnipeg Free Press (June 28th, 2010 & th Flying at our Museum December 26, 2010), CBC Radio (June 30 , 2010 with Terry McLeod), CTV News (June 30th, 2010), Stonewall Argus (Jan.27th, 2011 & Jan 22, 2014). The flags continue to positively promote both our museum and their original organizations. As a sign of respect for our flags, we display them in accordance with Canadian Flag Etiquette, as outlined by the Government of Canada. Rev. March 23, 2014 Canadian Flag Collection Flag Acquisition Policy Settlers, Rails & Trails obtains flags from a variety of sources. We generally ask interested parties for a donation of a flag, without the requirement of further monetary contribution. Donors usually choose to have the flag mailed to our museum, however, arrangements could be made for local pick-up. -

Downtown Old St. Boniface

Oseredok DISRAELI FWY Heaton Av Chinese GardensJames Av Red River Chinatown Ukrainian George A Hotels Indoor Walkway System: Parking Lot Parkade W College Gomez illiam A Gate Cultural Centre Museums/Historic Structures Main Underground Manitoba Sports Argyle St aterfront Dr River Spirit Water Bus Canada Games Edwin St v Civic/Educational/Office Buildings Downtown Winnipeg & Old St. Boniface v Hall of Fame W Sport for Life Graham Skywalk Notre Dame Av Cumberland A Bannatyne A Centre Galt Av i H Services Harriet St Ellen St Heartland City Hall Alexander Av Shopping Neighbourhoods Portage Skywalk Manitoba Lily St Gertie St International Duncan St Museum Malls/Dept. Stores/Marketplaces St. Mary Skywalk Post Office English School Council Main St The v v Centennial Tom Hendry P Venues/Theatres Bldg acific A Currency N Frances St McDermot A Concert Hall Theatre 500 v Province-Wide Arteries 100 Pantages Building Entrances Pharmacy 300 Old Market v Playhouse Car Rental Square Theatre Amy St Walking/Cycling Trails Adelaide St Dagmar St 100 Mere Alexander Dock City Route Numbers Theatre James A Transit Only Spence St Hotel Princess St (closed) Artspace Exchange Elgin Av aterfront Dr Balmoral St v Hargrave St District BIZ The DistrictMarket A W Cinematheque John Hirsch Scale approx. Exchange 200 John Hirsch Pl Notre Dame A Theatre v Fort Gibraltar 100 0 100 200 m Carlton St Bertha St and Maison Edmonton St National Historic Site Sargent Av Central District du Bourgeois K Mariaggi’s Rorie St ennedy St King St Park v 10 Theme Suite Towne Bannatyne -

Waters Fur Trade 9/06.Indd

WATERS OF THE FUR TRADE Self-Directed Drive & Paddle One or Two Day Tour Welcome to a Routes on the Red self-directed tour of the Red River Valley. These itineraries guide you through the history and the geography of this beautiful and interesting landscape. Several different Routes on the Red, featuring driving, cycling, walking or canoeing/kayaking, lead you on an exploration of four historical and cultural themes: Fur Trading Routes on the Red; Settler Routes on the Red; Natural and First Nations Routes on the Red; and Art and Cultural Routes on the Red. The purpose of this route description is to provide information on a self-guided drive and canoe/kayak trip. While you enjoy yourself, please drive and canoe or kayak carefully as you are responsible to ensure your own safety and that these activities are within your skill and abilities. Every effort has been made to ensure that the information in this description is accurate and up to date. However, we are unable to accept responsibility for any inconvenience, loss or injury sustained as a result of anyone relying upon this information. Embark on a one or two day exploration of the Red River and plentiful waters of the Red. At the end of your second day, related waters. Fur trading is the main theme including a canoe you will have a lovely drive back to Winnipeg along the east or kayak paddle along the Red River to arrive at historic Lower side of the Red River. Fort Garry and its costumed recreation and interpretation of Accommodations in Selkirk are listed at the end of Day 1. -

CHRONICLES of CANADA Edited by George M

ST .VII4VIII Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.org/details/chroniclesofcana21wron CHRONICLES OF CANADA Edited by George M. Wrong and H. H. Langton In thirty-two volumes 21 THE RED RIVER COLONY BY LOUIS AUBREY WOOD Part VI Pioneers of the North and West THOMAS DOUGLAS, FIFTH EARL OF SELKIRK From the painting at St Mary’s Isle THE RED RIVER COLONY A Chronicle of the Beginnings of Manitoba BY LOUIS AUBREY WOOD TORONTO GLASGOW, BROOK & COMPANY 1922 Copyright in all Countries subscribing to the Berne Convention tc\uc . F SoSJ C55 C. I 0. TO MY FATHER 115623 CONTENTS Page I. ST MARY’S ISLE i II. SELKIRK, THE COLONIZER .... 9 III. THE PURSE-STRINGS LOOSEN ... 22 IV. STORNOWAY-AND BEYOND ... 35 V. WINTERING ON THE BAY .... 44 VI. RED RIVER AND PEMBINA .... 54 VII. THE BEGINNING OF STRIFE ... 65 VIII. COLIN ROBERTSON, THE AVENGER . 80 IX. SEVEN OAKS 91 X. LORD SELKIRK’S JOURNEY . .108 XL FORT WILLIAM 116 XII. THE PIPE OF PEACE 129 BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTE . .142 INDEX ...... .147 ix ILLUSTRATIONS THOMAS DOUGLAS, FIFTH EARL OF SELKIRK ...... Frontispiece From the painting at St Mary’s Isle. PLACE D’ARMES, MONTREAL, IN 1807 . Facing page 20 From a water-colour sketch after Dillon in M'Gill University Library. JOSEPH FROBISHER, A PARTNER IN THE NORTH-WEST COMPANY ... „ 22 From an engraving in the John Ross Robertson Collection, Toronto Public Library. THE COUNTRY OF LORD SELKIRK’S SETTLERS 48 Map by Bartholomew. HUNTING THE BUFFALO ... ,,58 From a painting by George Catlin. PLAN OF THE RED RIVER COLONY. -

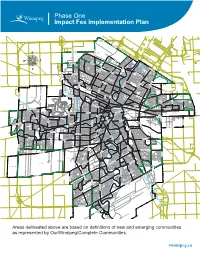

Impact Fee Implementation Plan

Phase One Impact Fee Implementation Plan ROSSER-OLD KILDONAN AMBER TRAILS RIVERBEND LEILA NORTH WEST KILDONAN INDUSTRIAL MANDALAY WEST RIVERGROVE A L L A TEMPLETON-SINCLAIR H L A NORTH INKSTER INDUSTRIAL INKSTER GARDENS THE MAPLES V LEILA-McPHILLIPS TRIANGLE RIVER EAST MARGARET PARK KILDONAN PARK GARDEN CITY SPRINGFIELD NORTH INKSTER INDUSTRIAL PARK TYNDALL PARK JEFFERSON ROSSMERE-A KILDONAN DRIVE KIL-CONA PARK MYNARSKI SEVEN OAKS ROBERTSON McLEOD INDUSTRIAL OAK POINT HIGHWAY BURROWS-KEEWATIN SPRINGFIELD SOUTH NORTH TRANSCONA YARDS SHAUGHNESSY PARK INKSTER-FARADAY ROSSMERE-B BURROWS CENTRAL ST. JOHN'S LUXTON OMAND'S CREEK INDUSTRIAL WESTON SHOPS MUNROE WEST VALLEY GARDENS GRASSIE BROOKLANDS ST. JOHN'S PARK EAGLEMERE WILLIAM WHYTE DUFFERIN WESTON GLENELM GRIFFIN TRANSCONA NORTH SASKATCHEWAN NORTH DUFFERIN INDUSTRIAL CHALMERS MUNROE EAST MEADOWS PACIFIC INDUSTRIAL LORD SELKIRK PARK G N LOGAN-C.P.R. I S S NORTH POINT DOUGLAS TALBOT-GREY O R C PEGUIS N A WEST ALEXANDER N RADISSON O KILDARE-REDONDA D EAST ELMWOOD L CENTENNIAL I ST. JAMES INDUSTRIAL SOUTH POINT DOUGLAS K AIRPORT CHINA TOWN C IVIC CANTERBURY PARK SARGENT PARK CE TYNE-TEES KERN PARK NT VICTORIA WEST RE DANIEL McINTYRE EXCHANGE DISTRICT NORTH ST. BONIFACE REGENT MELROSE CENTRAL PARK SPENCE PORTAGE & MAIN MURRAY INDUSTRIAL PARK E TISSOT LLIC E-E TAG MISSION GARDENS POR TRANSCONA YARDS HERITAGE PARK COLONY SOUTH PORTAGE MISSION INDUSTRIAL THE FORKS DUGALD CRESTVIEW ST. MATTHEWS MINTO CENTRAL ST. BONIFACE BUCHANAN JAMESWOOD POLO PARK BROADWAY-ASSINIBOINE KENSINGTON LEGISLATURE DUFRESNE HOLDEN WEST BROADWAY KING EDWARD STURGEON CREEK BOOTH ASSINIBOIA DOWNS DEER LODGE WOLSELEY RIVER-OSBORNE TRANSCONA SOUTH ROSLYN SILVER HEIGHTS WEST WOLSELEY A NORWOOD EAST STOCK YARDS ST. -

Summary of Results: 2018 Manitoba 55 Plus Games

Summary of Results: 2018 Manitoba 55 Plus Games Event Name or Team Region 1 km Predicted Nordic Walk Gold Steen Raymond Interlake Silver Mitchell Lorelie Westman Bronze Klassen Sandra Eastman 3 km Predicted Walk/Run Gold Spiring Britta Assiniboine Park/Fort Garry Silver Reavie Cheryl Parkland Bronze Heidrick Wendy Fort Garry/Assiniboia 16km Predicted Cycle Gold Jones Norma City Centre Silver Hansen Bob City Centre Bronze Moore Bob Westman 5 Pin Bowling Singles Women 55+ Gold MARION SINGLE Central Plains Silver SHARON PROST Westman Bronze SHIRLEY CHUBEY Eastman Women 65+ Gold OLESIA KALINOWICH Parkland Silver BEV VANDAMME Parkland Bronze RHONDA VAUDRY Westman Women 75+ Gold JEAN YASINSKI EK/Transcona Silver VICKY BEYKO Parkland Bronze DONNA GARLAND Westman Women 85+ Gold GRACE JONES Westman Silver EVA HARRIS EK/Transcona Men 55+ Gold DES MURRAY Westman Silver JERRY SKRABEK Ek/Transcona Bronze BERNIE KIELICH Eastman Men 65+ Gold HARVEY VAN DAMME Parkland Silver FRANK AARTS Westman Bronze JAKE ENNS Westman Men 75+ Gold FRANK REIMER Eastman Silver MARRIS BOS Central Plains Bronze NESTOR KALINOWICH Parkland Men 85+ Gold HARRY DOERKSEN EK/Transcona Silver LEO LANSARD EK/Transcona Bronze MELVIN OSWALD Westman 5 Pin Bowling Team 55+ Mixed Gold Carberry 1 Westman Silver OK Gals Westman Bronze Plumas Pin Pals Central Plains 65+ Mixed Gold Carberry 2 Westman Silver Parkland Parkland Bronze Hot Shots Westman 75+ Mixed Gold EK/Transcona EK/Transcona Silver Blumenort Eastman Bronze Strike Force Parkland 8 Ball 55+ Gold Dieter Bonas Assiniboine Park/Fort Garry Silver Rheal Simon Pembina Valley Bronze Guy Jolicoeur Eastman 70+ Gold Alfred Zastre Parkland Silver Denis Gaudet St. -

Celebrate 150 Spend Time in the Great Outdoors

150 Things to Do in Manitoba CELEBRATE 150 1. Unite 150 Head to the Manitoba Legislative Building this summer for an epic (and FREE) concert that celebrates Manitoba 150. There will be 3 stages with BIG acts from across Canada. Can’t make it? The entire spectacle will be streamed live across Manitoba. *BONUS: Download the Manitoba 150 app to explore new landmarks throughout the province, with the chance to win some amazing prizes. 2. Tour 150 The Winnipeg Art Gallery is hitting the road in 2020 to bring a mini- gallery on wheels to communities and towns throughout the province. SPEND TIME IN THE GREAT OUTDOORS Pinawa Channel 3. Float down the Pinawa Channel If floating peacefully down a lazy river seems appealing to you this summer, don’t miss the opportunity to take in the gorgeous scenery of the Pinawa Channel! There are two companies to rent from: Wilderness Edge Resort and Float & Paddle. 4. Learn to winter camp You may be a seasoned camper in the summer months - but have you tried it in the cold nights of winter? Wilderland Adventure Company is offering a variety of traditional winter camping experiences in Sandilands Provincial Forest, Whiteshell Provincial Park and Riding Mountain National Park. oTENTik at Riding Mountain National Park Pinawa Dam Photo Credit: Max Muench 5. Take a self-guided tour of Pinawa Dam Provincial Park Get a closer look at Manitoba’s first year-round generating plant on the Dam Ruins Walk in Pinawa Dam Provincial Park. There are 13 interpretive signs along the way! 6. -

Pimachiowin Aki Annual Report 2017

Annual Report 2017 Pimachiowin Aki Corporation Pimachiowin Aki Corporation is a non-profit organization working to achieve international recognition for an Anishinaabe cultural landscape in the boreal forest in central Canada as a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Site. Members of the Pimachiowin Aki Corporation include the First Nations of Bloodvein River, Little Grand Rapids, Pauingassi and Poplar River and the provinces of Manitoba and Ontario The Corporation’s Mission “To acknowledge and support the Anishinaabe culture and safeguard the boreal forest; preserving a living cultural landscape to ensure the well-being of the Anishinaabe who live here and for the benefit and enjoyment of all people.” The Corporation’s Objectives • To create an internationally recognized network of linked protected areas (including aboriginal ancestral lands) which is worthy of UNESCO World Heritage inscription; • To seek support and approval from governments of First Nations, Ontario, Manitoba, and Canada to complete the nomination process and achieve UNESCO designation; • To enhance cooperative relationships amongst members in order to develop an appropriate management framework for the area; and • To solicit governments and private organizations in order to raise funds to implement the objectives of the Corporation. Table of Contents Message from the Co-Chairs ..................................................................................................................................1 Board of -

2015 Report on Park Assets

Appendix A 2015 Report on Park Assets Asset Management Branch Parks and Open Space Division Public Works Department Table of Contents Summary of Parks, Assets and Asset Condition by Ward Charleswood-Tuxedo-Whyte Ridge Ward ................................................................................................... 1 Daniel McIntyre Ward .................................................................................................................................. 9 Elmwood – East Kildonan Ward ................................................................................................................. 16 Fort Rouge – East Fort Garry Ward ............................................................................................................ 24 Mynarski Ward ........................................................................................................................................... 32 North Kildonan Ward ................................................................................................................................. 40 Old Kildonan Ward ..................................................................................................................................... 48 Point Douglas Ward.................................................................................................................................... 56 River Heights – Fort Garry Ward ................................................................................................................ 64 South Winnipeg – St. Norbert -

«En Paroles Et En Gestes: Portraits De Femmes Du Manitoba Français»

CAHIERS FRANCO-CANADIENS DE L'OUEST VOL. 10, No 1, 1998, p. 187-234 «EN PAROLES ET EN GESTES: PORTRAITS DE FEMMES DU MANITOBA FRANÇAIS» Exposition présentée par le Musée de Saint-Boniface en collaboration avec Réseau 188 CAHIERS FRANCO-CANADIENS DE L'OUEST, 1998 REMERCIEMENTS: Réseau et le Musée de Saint-Boniface remercient particulièrement les familles et les amis des femmes présentées ainsi que toutes les personnes dont la générosité a permis la réalisation de cette exposition. Réseau tient à souligner la contribution financière du ministère du Patrimoine canadien qui a appuyé toutes les étapes de ce grand projet. COMITÉ D’EXPOSITION RÉSEAU: Denise Albert, Annie Bédard, Carole Boily, Pierrette Boily, Stéphanie Gagné et Sylvie Ross. CONTRIBUTIONS À LA RECHERCHE: Bertrand Boily, Carole Boily, Pierrette Boily, Lynne Champagne, Jacqueline Comeau, Diane Payment, Janelle Reynolds, Farha Salim, Corinne Tellier et Hélène Vrignon. EXPOSITION: «EN PAROLES ET EN GESTES...» 189 Cette exposition rend hommage à une vingtaine de femmes d’origine franco-manitobaine ou qui ont vécu au Manitoba français dans des conditions diverses et pendant une époque qui s’étend sur deux siècles. Seules quelques-unes ont atteint la renommée; les autres sont relativement inconnues. Elles ont mené leur vie souvent dans le cadre des contraintes de leur société, dans les rôles réservés aux femmes – soigner, aider, éduquer dans la langue française et la foi catholique. Donc, on retrouve une forte concentration de femmes dans les œuvres de charité et dans l’éducation. Certaines ont dépassé ces limites ou ont développé d’autres talents, et ont œuvré dans des domaines, tels les affaires ou les arts, qui étaient moins encouragés lorsqu’il s’agissait du sexe féminin. -

Canadianism, Anglo-Canadian Identities and the Crisis of Britishness, 1964-1968

Nova Britannia Revisited: Canadianism, Anglo-Canadian Identities and the Crisis of Britishness, 1964-1968 C. P. Champion Department of History McGill University, Montreal A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History February 2007 © Christian Paul Champion, 2007 Table of Contents Dedication ……………………………….……….………………..………….…..2 Abstract / Résumé ………….……..……….……….…….…...……..………..….3 Acknowledgements……………………….….……………...………..….…..……5 Obiter Dicta….……………………………………….………..…..…..….……….6 Introduction …………………………………………….………..…...…..….….. 7 Chapter 1 Canadianism and Britishness in the Historiography..….…..………….33 Chapter 2 The Challenge of Anglo-Canadian ethnicity …..……..…….……….. 62 Chapter 3 Multiple Identities, Britishness, and Anglo-Canadianism ……….… 109 Chapter 4 Religion and War in Anglo-Canadian Identity Formation..…..……. 139 Chapter 5 The celebrated rite-de-passage at Oxford University …….…...…… 171 Chapter 6 The courtship and apprenticeship of non-Wasp ethnic groups….….. 202 Chapter 7 The “Canadian flag” debate of 1964-65………………………..…… 243 Chapter 8 Unification of the Canadian armed forces in 1966-68……..….……. 291 Conclusions: Diversity and continuity……..…………………………….…….. 335 Bibliography …………………………………………………………….………347 Index……………………………………………………………………………...384 1 For Helena-Maria, Crispin, and Philippa 2 Abstract The confrontation with Britishness in Canada in the mid-1960s is being revisited by scholars as a turning point in how the Canadian state was imagined and constructed. During what the present thesis calls the “crisis of Britishness” from 1964 to 1968, the British character of Canada was redefined and Britishness portrayed as something foreign or “other.” This post-British conception of Canada has been buttressed by historians depicting the British connection as a colonial hangover, an externally-derived, narrowly ethnic, nostalgic, or retardant force. However, Britishness, as a unique amalgam of hybrid identities in the Canadian context, in fact took on new and multiple meanings.