Artificial Glaciers and the Politics of Place in a High-Altitude Himalayan Village

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ice Stupas and Water Security November 2017 Volume 31 Number 2

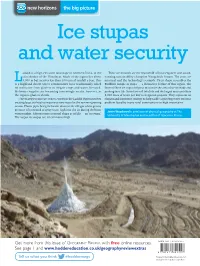

new horizons the big picture A-level geography Ice stupas and water security November 2017 Volume 31 Number 2 adakh is a high-elevation landscape in northern India, in the These ice mounds are the brainchild of local engineer and award- rain shadow of the Himalayas. Much of the region lies above winning sustainability champion Wangchuck Sonam. The costs are L3,000 m but receives less than 100 mm of rainfall a year. This minimal and the technology is simple. Their shape resembles the Contested is a highland desert where communities have traditionally relied Buddhist temple or stupa — a distinctive feature of this region. The on meltwater from glaciers to irrigate crops and water livestock. form of these ice stupas helps to maximise the area of ice in shade and Meltwater supplies are becoming increasingly erratic, however, as prolong their life. Some last well into July and the largest may contribute the region’s glaciers shrink. 5,000 litres of water per day to irrigation projects. They represent an One strategy to increase water security in the Ladakh region involves elegant and ingenious strategy to help tackle a growing water-resource ocean spaces creating large artificial ice masses to store water for the summer growing problem faced by many rural communities in high mountains. season. Plastic pipes bring meltwater down to the villages where gravity pressure is harnessed to spray water high into the air during the bitter Territorial disputes in Jamie Woodward is professor of physical geography at The winter nights. It freezes into a conical shape as it falls — an ‘ice stupa’. -

Monsoon-Influenced Glacier Retreat in the Ladakh Range, Jammu And

Geophysical Research Abstracts Vol. 18, EGU2016-166, 2016 EGU General Assembly 2016 © Author(s) 2015. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Monsoon-influenced glacier retreat in the Ladakh Range, Jammu and Kashmir Tom Chudley, Evan Miles, and Ian Willis Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge ([email protected]) While the majority of glaciers in the Himalaya-Karakoram mountain chain are receding in response to climate change, stability and even growth is observed in the Karakoram, where glaciers also exhibit widespread surge- type behaviour. Changes in the accumulation regime driven by mid-latitude westerlies could explain such stability relative to the monsoon-fed glaciers of the Himalaya, but a lack of detailed meteorological records presents a challenge for climatological analyses. We therefore analyse glacier changes for an intermediate zone of the HKH to characterise the transition between the substantial retreat of Himalayan glaciers and the surging stability of Karakoram glaciers. Using Landsat imagery, we assess changes in glacier area and length from 1991-2014 across a ∼140 km section of the Ladakh Range, Jammu and Kashmir. Bordering the surging, stable portion of the Karakoram to the north and the Western Himalaya to the southeast, the Ladakh Range represents an important transitional zone to identify the potential role of climatic forcing in explaining differing glacier behaviour across the region. A total of 878 glaciers are semi-automatically identified in 1991, 2002, and 2014 using NDSI (thresholds chosen between 0.30 and 0.45) before being manually corrected. Ice divides and centrelines are automatically derived using an established routine. Total glacier area for the study region is in line with that Randolph Glacier Inventory (RGI) and ∼25% larger than the GLIMS Glacier Database, which is apparently more conservative in assigning ice cover in the accumulation zone. -

23D Markha Valley Trek

P.O Box: 26106 Kathmandu Address: Thamel, Kathmandu, Nepal Phone: +977 1 5312359 Fax: +977 1 5351070 Email: [email protected] India: 23d Markha Valley Trek Grade: Easy Altitude: 5,150 m. Tent Days: 10 Highlights: Markha Valley Trekking is one of the most varied and beautiful treks of Nepal. It ventures high into the Himalayas crossing two passes over 4575m. As it circles from the edges of the Indus Valley, down into parts of Zanskar. The trekking route passes through terrain which changes from incredibly narrow valleys to wide-open vast expanses. Markha valley trek becomes more interesting by the ancient form of Buddhism that flourishes in the many monasteries. The landscape of this trek is perched with high atop hills. The trails are decorated by elaborate “charters”(shrines) and “Mani”(prayer) walls. That further exemplifies the region’s total immersion in Buddhist culture. As we trek to the upper end of the Markha Valley, we are rewarded with spectacular views of jagged snow-capped peaks before crossing the 5150m Kongmaru La (Pass) and descending to the famous Hemis Monastery, where we end our trek. This trekking is most enjoyable for those who want to explore the ancient Buddhism with beautiful views of Himalayas. Note: B=Breakfast, L= Lunch, D=Dinner Day to day: Day 1: Arrival at Delhi o/n in Hotel : Reception at the airport, transfer and overnight at hotel. Day 2: Flight to Leh (3500m) o/n in Hotel +B: Transfer to domestic airport in the morning flight to Leh. Transfer to hotel, leisurely tour of the city to acclimatize: the old bazaar, the Palace, the Shanti Stupa, mosque; afternoon free. -

Government of India Ministry of Jal Shakti Department of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation (National Water Mission) *****

Government of India Ministry of Jal Shakti Department of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation (National Water Mission) ***** National Water Mission (NWM) has initiated a seminar series- ‘Water Talk’ - to promote dialogue and information sharing among participants on variety of water related topics. The ‘Water Talk’ is intended to create awareness, build capacities of stakeholders and to encourage people to become active participants in conservation and saving of water. NWM had already organized five ‘Water-Talks’ on the topics - “Water for All”, “Groundwater” “Water Conservation”, “Ecology Inclusive Economy”, “Agriculture, Groundwater and Energy nexus” and “Water conservation at Hiware Bazaar in Maharashtra and Dewas in Madhya Pradesh” on 22nd March 2019, 1st May 2019, 24th May 2019, 21st June 2019, 19th July 2019 and 23rd August 2019 respectively. 2. Seventh Water Talk in this series was held on 20th September, 2019. Shri Sonam Wangchuk, Founder, Himalayan Institute of Alternatives delivered the Water Talk. Shri Rajiv Ranjan Mishra, DG, NMCG; Officers from CWC, CGWB, NMCG, CSMRS, NWDA and D/o WR, RD & GR and Researchers from various institutes attended the programme. 3. Shri Sonam Wangchuk delivered the talk on ‘Innovation and Water’ and discussed the need of innovative water conservation methods in the terrain of Ladakh. Shri Wangchuk started his talk by explaining the extremities of this region. Ladakh is a cold high altitude dessert. Farming and livelihood depends on the melted water of glaciers, but due to climate change the glaciers which were near to villages have receded far away. He said that most villages face acute water shortage, particularly during the two crucial months of April and May when there is little water in the streams and all the villagers compete to water their newly planted crops. -

Glacier Characteristics and Retreat Between 1991 and 2014 in the Ladakh Range, Jammu and Kashmir

February 24, 2017 Remote Sensing Letters chudley-ladakh-manuscript To appear in Remote Sensing Letters Vol. 00, No. 00, Month 20XX, 1{17 Glacier characteristics and retreat between 1991 and 2014 in the Ladakh Range, Jammu and Kashmir THOMAS R. CHUDLEYy∗, EVAN S. MILESy and IAN C. WILLISy yScott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK (Received 29th November 2016) The Ladakh Range is a liminal zone of meteorological conditions and glacier changes. It lies between the monsoon-forced glacier retreat of the Himalaya and Zanskar ranges to the south and the anomalous stability observed in the Karakoram to the north, driven by mid-latitude westerlies. Given the climatic context of the Ladakh Range, the glaciers in the range might be expected to display intermediate behaviour between these two zones. However, no glacier change data have been compiled for the Ladakh Range itself. Here, we examine 864 glaciers in the central section of the Ladakh range, covering a number of smaller glaciers not included in alternative glacier inventories. Glaciers in the range are small (median 0.25 km2; maximum 6.58 km2) and largely distributed between 5000-6000 m above sea level (a.s.l.). 657 glaciers are available for multitemporal analysis between 1991 to 2014 using data from Landsat multispectral sensors. We find glaciers to have retreated -12.8% between 1991{2014. Glacier changes are consistent with observations in the Western Himalaya (to the south) and in sharp contrast with the Karakoram (to the north) in spite of its proximity to the latter. We suggest this sharp transition must be explained at least in part by non-climatic mechanisms (such as debris covering or hypsometry), or that the climatic factors responsible for the Karakoram behaviour are extremely localised. -

Eco-Rehabilitation of Tribal Villages Through Innovative Design in Water

Eco-Rehabilitation of tribal villages through Innovative design in water management using Ice-stupa, promoting Farm-stay tourism and passive solar heating system- Joint Inititative of Tribal Affairs and Secmol in Leh The “roof of the world”, the metaphorical description for the physio-geographic region encompassing the Indian Himalayas, is the site of vast freshwater glaciers and the primary source of the major Asian rivers that have sustained life since early human civilisations have inhabited the area. In modern times, these freshwater glaciers are still the primary source of water, and thus the welfare, for over a billion Asian people, especially for the tribal communities of Ladakh who have been perpetually dependent on glacial meltwater in the high-altitude desert. Lying on the northerly fringes of the Himalayan watershed, Ladakh is characterised by distinct geographical and climatic features. Known as a cold desert, Ladakh covers area of 96701 km2 and with an average elevation of 3000 m, having annual annual precipitation100 mm, and extreme temperatures ranges (-30 to 30 Co). Much of the province remains in a cold spell from October-March, with only a third of the year left for agrarian purposes. The villages in the region are settled in small oases in the barren desert, on the banks of a stream, or amongst springs utilising the summertime meltwater. Regardless of its ecosystem services and historical context, reckless human interventions and global climate change have impacted the region immeasurably, in particular due to the escalated rate of warming at higher altitudes. Currently, Himalayan glaciers are receding at an alarming rate, from a few to tens of meters annually. -

07 Nights / 08 Days Leh Ladakh

07 Nights / 08 Days Leh Ladakh DAT SECTOR PROGRAMME DESCRIPTION E S In time transfer to airport to connect the flight for Leh. Meeting and assistance on arrival and transfer to Hotel. Rest day at leisure to Acclimatize till 4 O’clock. PM walk upto Samker Gompa & Leh Bazaar. Day Delhi / Samker Gompa is little up in the valley, 01 Leh 3 Kms from Leh Town, which is open to visitors in the morning and evening only. The Gompa belongs to Yellow Sect & was founded in 18th Century. The Gompa is the seat of the Head Lama of Ladakh & founder of yellow sect, Tson-Kha-Pa. The temple walls have recent painted of figures including Sakyamuni, Avalokiteshwara, Padmasambhava, Tson-Ka-pa and green Tara. After Samker, visit Leh Temple & Walk back to Leh Bazaar through the famous Leh Polo Ground. Overnight & All meals in Hotel. Arrive : Uleytokpo on arrival check-in at Uleytokpo Camp & Resort. Enroute from Leh to Uleytokpo Visit the village of Nimo and stop for photo session at River Zanskar Proceed further to visit Basgo Fort & Likir. Likir is situated in a Leh – side valley about 05 Kms from main Uleytokp Srinagar – Leh highway. Likir belongs to Day o Ge-Lung-Pa sect; the monastery also 02 70 KMS maintains and runs a school for young – One Lamas. Afterwards cross river Indus and reach Alchi. A Beautiful way village covered with Apricot Orchards. On arrival check-in at 3040 Uleytokpo Camp & Resort. After lunch drive to Alchi Gompa which is MTRS 9 Kms from Uleytokpo from the most beautiful Gompa of Ladakh & is also called Jewel among the central Ladakh’ s religious sites. -

Phyang Monastery Life, Learnings and More from Ladakh by Prof

D’source 1 Digital Learning Environment for Design - www.dsource.in Design Resource Phyang Monastery Life, Learnings and More from Ladakh by Prof. Sumant Rao and Ruchi Shah IDC, IIT Bombay Source: http://www.dsource.in/resource/phyang-monastery 1. About Phyang 2. Phyang Monastery 3. Contact Details D’source 2 Digital Learning Environment for Design - www.dsource.in Design Resource About Phyang Phyang Monastery Life, Learnings and More from Ladakh Phyang is a small village located just outside Leh. It owes its popularity to the Phyang monastery which is named by after a blue mountain. It is also well known as a trekking destination. Being a hilly region, where people live and Prof. Sumant Rao and Ruchi Shah practice cultivation Phyang has a 2,000 people - strong population, with around 500 houses but just a few tourist IDC, IIT Bombay accommodations. Gang Ngonpo - The blue mountain, and Stok Kangri a snow-covered peak are located beyond it. The 600-year- old monastery is perched upon a hilltop, the village lays below with 1-2 storeyed houses amidst the yellow-green fields that are broken visually by zigzagged borders made of heaped stones. Phyang suffered heavy damages during the cloudburst in 2010, however the monastery remained relatively safe due to its high ground. Source: http://www.dsource.in/resource/phyang-monastery/ about-phyang 1. About Phyang 2. Phyang Monastery 3. Contact Details D’source 3 Digital Learning Environment for Design - www.dsource.in Design Resource Phyang Monastery Phyang Monastery Life, Learnings and More from Ladakh The Phyang Monastery was established in 1515. -

6 Nights & 7 Days Leh – Nubra Valley (Turtuk Village)

Jashn E Navroz | Turtuk, Ladakh | Dates 25March-31March’18 |6 Nights & 7 Days Destinations Leh Covered – Nubra : Leh Valley – Nubra (Turtuk Valley V illage)(Turtuk– Village Pangong ) – Pangong Lake – Leh Lake – Leh Trip starts from : Leh airport Trip starts at: LehTrip airport ends at |: LehTrip airport ends at: Leh airport “As winter gives way to spring, as darkness gives way to light, and as dormant plants burst into blossom, Nowruz is a time of renewal, hope and joy”. Come and experience this festive spirit in lesser explored gem called Turtuk. The visual delights would be aptly complemented by some firsthand experiences of the local lifestyle and traditions like a Traditional Balti meal combined with Polo match. During the festival one get to see the flamboyant and vibrant tribe from Balti region, all dressed in their traditional best. Day 01| Arrive Leh (3505 M/ 11500 ft.) Board a morning flight and reach Leh airport. Our representative will receive you at the terminal and you then drive for about 20 minutes to reach Leh town. Check into your room. It is critical for proper acclimatization that people flying in to Leh don’t indulge in much physical activity for at least the first 24hrs. So the rest of the day is reserved for relaxation and a short acclimatization walk in the vicinity. Meals Included: L & D Day 02| In Leh Post breakfast, visit Shey Monastery & Palace and then the famous Thiksey Monastery. Drive back and before Leh take a detour over the Indus to reach Stok Village. Enjoy a traditional Ladakhi meal in a village home later see Stok Palace & Museum. -

World Water Week (August 26-30, 2019): Putting the Spotlight on India

World Water Week (August 26-30, 2019): Putting the Spotlight on India A boy stores water from a tap at Nidamanuru near Vijayawada, Andhra Pradesh (Photo: Mahesh G/ TOI,BCCL,VIJAYAWADA) As representatives from 100 countries meet in Stockholm, Sweden, for the World Water Week conference (August 25-30, 2019) organised by the Stockholm International Water Institute (SIWI), the Weather Channel puts the spotlight on water management, policy and innovation in India. Read more here. World Water Week: Five Troubling Facts about India’s Water Crisis This World Water Week, we take an in-depth look at the five troubling facts about India’s water crisis, ranging from economic growth and groundwater consumption to extreme rainfall events. Go through the list here. Thefts, Fights and Murder: Water Scarcity is Making Chennai an Angry City In June 2019, just as the country began to slowly cool down with the delayed onset of the southwest monsoon, Tamil Nadu continued facing one of its worst water crises. Lack of water subsequently triggered rise in disputes, violent clashes, and an increased overall violence amongst neighbours. More details here. 3 Ms of Water Woes in India: Monsoon, Mismanagement and Massive Urbanisation Disruption to Earth’s self-sustaining hydrological cycle is enough to herald calamity, especially for an agriculture-driven, high-population economy like India’s. This disruption is caused mainly by monsoon, mismanagement and massive urbanisation. Prof Sridhar Balasubramanian explains about these 3 Ms here. Environmental Flow: How River’s Share of Water Can Preserve Ecosystem, Promote Well-being As per a recent World Wildlife Fund (WWF) study, just one-third of the world’s 246 longest rivers remain free-flowing today. -

`15,999/-(Per Person)

BikingLEH Adventure 06 DAYS OF THRILL STARTS AT `15,999/-(PER PERSON) Leh - Khardungla Pass - Nubra Valley - Turtuk - Pangong Tso - Tangste [email protected] +91 9974220111 +91 7283860777 1 ABOUT THE PLACES Leh, a high-desert city in the Himalayas, is the capital of the Leh region in northern India’s Jammu and Kashmir state. Originally a stop for trading caravans, Leh is now known for its Buddhist sites and nearby trekking areas. Massive 17th-century Leh Palace, modeled on the Dalai Lama’s former home (Tibet’s Potala Palace), overlooks the old town’s bazaar and mazelike lanes. Khardung La is a mountain pass in the Leh district of the Indian union territory of Ladakh. The local pronunciation is "Khardong La" or "Khardzong La" but, as with most names in Ladakh, the romanised spelling varies. The pass on the Ladakh Range is north of Leh and is the gateway to the Shyok and Nubra valleys. Nubra is a subdivision and a tehsil in Ladakh, part of Indian-administered Kashmir. Its inhabited areas form a tri-armed valley cut by the Nubra and Shyok rivers. Its Tibetan name Ldumra means "the valley of flowers". Diskit, the headquarters of Nubra, is about 150 km north from Leh, the capital of Ladakh. Turtuk is one of the northernmost villages in India and is situated in the Leh district of Ladakh in the Nubra Tehsil. It is 205 km from Leh, the district headquarters, and is on the banks of the Shyok River. Pangong Tso or Pangong Lake is an endorheic lake in the Himalayas situated at a height of about 4,350 m. -

A Sub Range of the Hindu Kush Himalayan Range. Ladakh Range Is a Mountain Range in Central Ladakh

A sub range of the Hindu Kush Himalayan range. Ladakh Range is a mountain range in central Ladakh. Karakoram range span its border between Pakistan, India & china. It lies between the Indus and Shyok river valleys, stretching to 230 miles. Karakoram serve as a watershed for the basin of the Indus and Yarkand river. Ladakh range is regarded as southern extension of the Karakoram range. K2, the second highest peak in the world is located here. Extension of the Ladakh range into china is known as Kailash range. Glacier like Siachen, and Biafo are found in this range. Ladakh Range Karakoram Range Mountain Ranges in India Pir panjal Range Zaskar Range Group of mountains in the Himalayas. Group of mountains in the Lesser Himalayan region, near They extended southeastward for some 400 mile from Karcha river the bank of Sutlej river. to the upper Karnali river. Separates Jammu hills to the south from the vale of Kashimr Lies here coldest place in India, Dras. (the gateway to Ladakh) beyond which lie the Great Himalayas. Kamet Peak is the highest point. Highest points Indrasan. Famous passes- Shipki, Lipu Lekh and Mana pass. Famous passes- Pir Panjal, Banihal pass, Rohtang pass. Part of lesser Himalayan chain of Mountains. Mountain range of the outer Himalayas that stretches from the Indus river about It rise from the Indian plains to the north of Kangra and Mandi. 2400 km eastwards close to the Brahmaputra river. The highest peak in this range is the Hanuman Tibba or 'White Mountain' A gap of about 90 km between the Teesta and Raidak river in Assam known approaches from Beas kund.