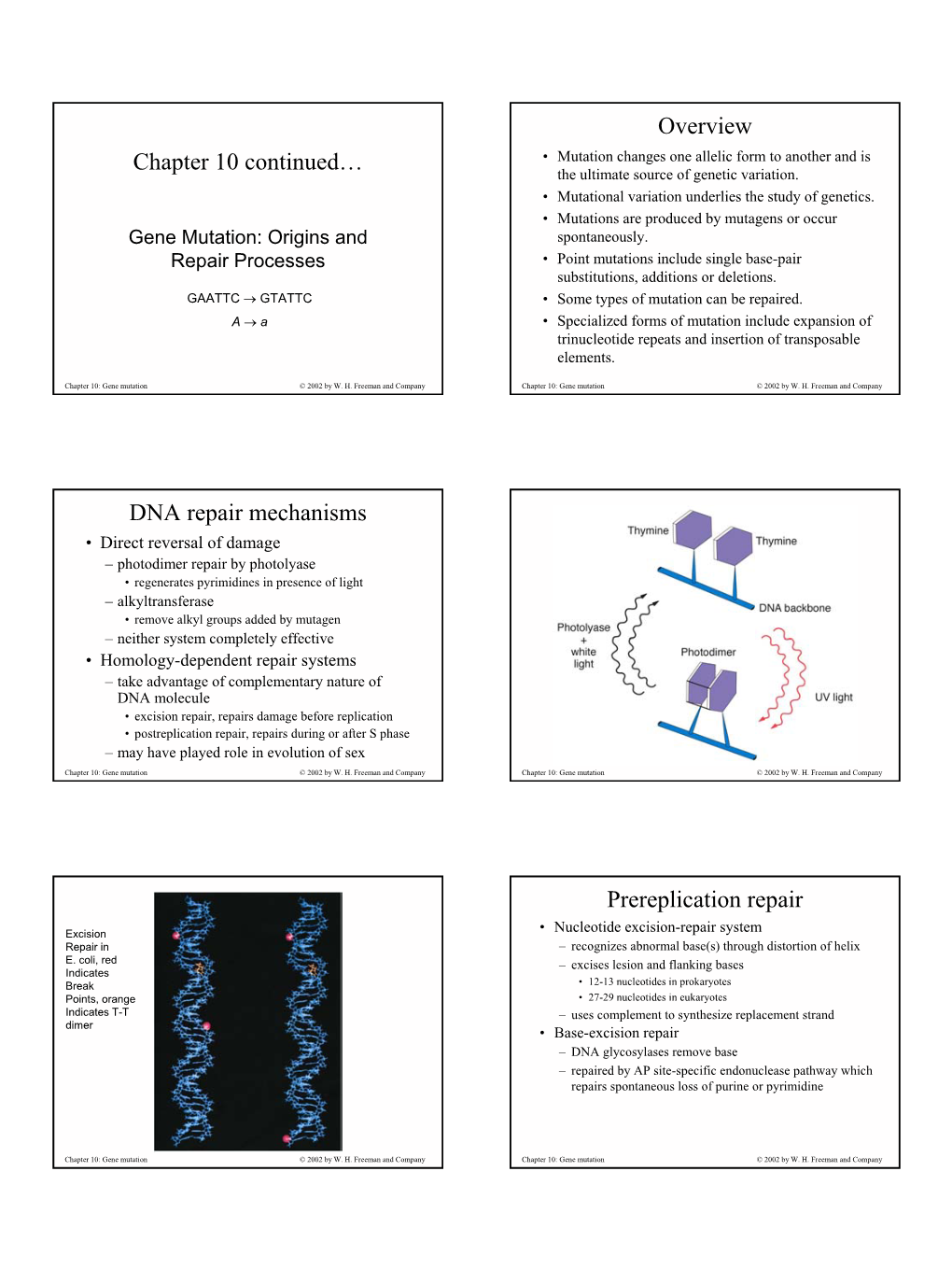

Overview DNA Repair Mechanisms Prereplication Repair

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolutionary Origins of DNA Repair Pathways: Role of Oxygen Catastrophe in the Emergence of DNA Glycosylases

cells Review Evolutionary Origins of DNA Repair Pathways: Role of Oxygen Catastrophe in the Emergence of DNA Glycosylases Paulina Prorok 1 , Inga R. Grin 2,3, Bakhyt T. Matkarimov 4, Alexander A. Ishchenko 5 , Jacques Laval 5, Dmitry O. Zharkov 2,3,* and Murat Saparbaev 5,* 1 Department of Biology, Technical University of Darmstadt, 64287 Darmstadt, Germany; [email protected] 2 SB RAS Institute of Chemical Biology and Fundamental Medicine, 8 Lavrentieva Ave., 630090 Novosibirsk, Russia; [email protected] 3 Center for Advanced Biomedical Research, Department of Natural Sciences, Novosibirsk State University, 2 Pirogova St., 630090 Novosibirsk, Russia 4 National Laboratory Astana, Nazarbayev University, Nur-Sultan 010000, Kazakhstan; [email protected] 5 Groupe «Mechanisms of DNA Repair and Carcinogenesis», Equipe Labellisée LIGUE 2016, CNRS UMR9019, Université Paris-Saclay, Gustave Roussy Cancer Campus, F-94805 Villejuif, France; [email protected] (A.A.I.); [email protected] (J.L.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (D.O.Z.); [email protected] (M.S.); Tel.: +7-(383)-3635187 (D.O.Z.); +33-(1)-42115404 (M.S.) Abstract: It was proposed that the last universal common ancestor (LUCA) evolved under high temperatures in an oxygen-free environment, similar to those found in deep-sea vents and on volcanic slopes. Therefore, spontaneous DNA decay, such as base loss and cytosine deamination, was the Citation: Prorok, P.; Grin, I.R.; major factor affecting LUCA’s genome integrity. Cosmic radiation due to Earth’s weak magnetic field Matkarimov, B.T.; Ishchenko, A.A.; and alkylating metabolic radicals added to these threats. -

The Role of Nucleotide Excision Repair in Restoring Replication Following UV-Induced Damage in Escherichia Coli

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Summer 1-1-2012 The Role of Nucleotide Excision Repair in Restoring Replication Following UV-Induced Damage in Escherichia coli Kelley Nicole Newton Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Biology Commons, and the Cell Biology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Newton, Kelley Nicole, "The Role of Nucleotide Excision Repair in Restoring Replication Following UV- Induced Damage in Escherichia coli" (2012). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 767. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.767 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. The Role of Nucleotide Excision Repair in Restoring Replication Following UV-Induced Damage in Escherichia coli by Kelley Nicole Newton A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Biology Thesis Committee: Justin Courcelle, Chair Michael Bartlett Jeffrey Singer Portland State University 2012 ABSTRACT Following low levels of UV exposure, Escherichia coli cells deficient in nucleotide excision repair recover and synthesize DNA at near wild type levels, an observation that formed the basis of the post replication recombination repair model. In this study, we characterized the DNA synthesis that occurs following UV-irradiation in the absence of nucleotide excision repair and show that although this synthesis resumes at near wild type levels, it is coincident with a high degree of cell death. -

Mechanism and Regulation of DNA Damage Recognition in Nucleotide Excision Repair

Kusakabe et al. Genes and Environment (2019) 41:2 https://doi.org/10.1186/s41021-019-0119-6 REVIEW Open Access Mechanism and regulation of DNA damage recognition in nucleotide excision repair Masayuki Kusakabe1, Yuki Onishi1,2, Haruto Tada1,2, Fumika Kurihara1,2, Kanako Kusao1,3, Mari Furukawa1, Shigenori Iwai4, Masayuki Yokoi1,2,3, Wataru Sakai1,2,3 and Kaoru Sugasawa1,2,3* Abstract Nucleotide excision repair (NER) is a versatile DNA repair pathway, which can remove an extremely broad range of base lesions from the genome. In mammalian global genomic NER, the XPC protein complex initiates the repair reaction by recognizing sites of DNA damage, and this depends on detection of disrupted/destabilized base pairs within the DNA duplex. A model has been proposed that XPC first interacts with unpaired bases and then the XPD ATPase/helicase in concert with XPA verifies the presence of a relevant lesion by scanning a DNA strand in 5′-3′ direction. Such multi-step strategy for damage recognition would contribute to achieve both versatility and accuracy of the NER system at substantially high levels. In addition, recognition of ultraviolet light (UV)-induced DNA photolesions is facilitated by the UV-damaged DNA-binding protein complex (UV-DDB), which not only promotes recruitment of XPC to the damage sites, but also may contribute to remodeling of chromatin structures such that the DNA lesions gain access to XPC and the following repair proteins. Even in the absence of UV-DDB, however, certain types of histone modifications and/or chromatin remodeling could occur, which eventually enable XPC to find sites with DNA lesions. -

Role of Apurinic/Apyrimidinic Nucleases in the Regulation of Homologous Recombination in Myeloma: Mechanisms and Translational S

Kumar et al. Blood Cancer Journal (2018) 8:92 DOI 10.1038/s41408-018-0129-9 Blood Cancer Journal ARTICLE Open Access Role of apurinic/apyrimidinic nucleases in the regulation of homologous recombination in myeloma: mechanisms and translational significance Subodh Kumar1,2, Srikanth Talluri1,2, Jagannath Pal1,2,3,XiaoliYuan1,2, Renquan Lu1,2,PuruNanjappa1,2, Mehmet K. Samur1,4,NikhilC.Munshi1,2,4 and Masood A. Shammas1,2 Abstract We have previously reported that homologous recombination (HR) is dysregulated in multiple myeloma (MM) and contributes to genomic instability and development of drug resistance. We now demonstrate that base excision repair (BER) associated apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) nucleases (APEX1 and APEX2) contribute to regulation of HR in MM cells. Transgenic as well as chemical inhibition of APEX1 and/or APEX2 inhibits HR activity in MM cells, whereas the overexpression of either nuclease in normal human cells, increases HR activity. Regulation of HR by AP nucleases could be attributed, at least in part, to their ability to regulate recombinase (RAD51) expression. We also show that both nucleases interact with major HR regulators and that APEX1 is involved in P73-mediated regulation of RAD51 expression in MM cells. Consistent with the role in HR, we also show that AP-knockdown or treatment with inhibitor of AP nuclease activity increases sensitivity of MM cells to melphalan and PARP inhibitor. Importantly, although inhibition 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; of AP nuclease activity increases cytotoxicity, it reduces genomic instability caused by melphalan. In summary, we show that APEX1 and APEX2, major BER proteins, also contribute to regulation of HR in MM. -

DNA Repair with Its Consequences (E.G

Cell Science at a Glance 515 DNA repair with its consequences (e.g. tolerance and pathways each require a number of apoptosis) as well as direct correction of proteins. By contrast, O-alkylated bases, Oliver Fleck* and Olaf Nielsen* the damage by DNA repair mechanisms, such as O6-methylguanine can be Department of Genetics, Institute of Molecular which may require activation of repaired by the action of a single protein, Biology, University of Copenhagen, Øster checkpoint pathways. There are various O6-methylguanine-DNA Farimagsgade 2A, DK-1353 Copenhagen K, Denmark forms of DNA damage, such as base methyltransferase (MGMT). MGMT *Authors for correspondence (e-mail: modifications, strand breaks, crosslinks removes the alkyl group in a suicide fl[email protected]; [email protected]) and mismatches. There are also reaction by transfer to one of its cysteine numerous DNA repair pathways. Each residues. Photolyases are able to split Journal of Cell Science 117, 515-517 repair pathway is directed to specific Published by The Company of Biologists 2004 covalent bonds of pyrimidine dimers doi:10.1242/jcs.00952 types of damage, and a given type of produced by UV radiation. They bind to damage can be targeted by several a UV lesion in a light-independent Organisms are permanently exposed to pathways. Major DNA repair pathways process, but require light (350-450 nm) endogenous and exogenous agents that are mismatch repair (MMR), nucleotide as an energy source for repair. Another damage DNA. If not repaired, such excision repair (NER), base excision NER-independent pathway that can damage can result in mutations, diseases repair (BER), homologous recombi- remove UV-induced damage, UVER, is and cell death. -

Fission Yeast Hsk1 (Cdc7) Kinase Is Required After Replication Initiation for Induced Mutagenesis and Proper Response to DNA Alkylation Damage

Copyright Ó 2010 by the Genetics Society of America DOI: 10.1534/genetics.109.112284 Fission Yeast Hsk1 (Cdc7) Kinase Is Required After Replication Initiation for Induced Mutagenesis and Proper Response to DNA Alkylation Damage William P. Dolan,*,† Anh-Huy Le,* Henning Schmidt,‡ Ji-Ping Yuan,* Marc Green* and Susan L. Forsburg*,1 *Molecular and Computational Biology Program, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California 90089, †Division of Biology, University of California, San Diego, California 92093 and ‡Institut fu¨r Genetik, TU Braunschweig, D-38106 Braunschweig, Germany Manuscript received November 20, 2009 Accepted for publication February 16, 2010 ABSTRACT Genome stability in fission yeast requires the conserved S-phase kinase Hsk1 (Cdc7) and its partner Dfp1 (Dbf4). In addition to their established function in the initiation of DNA replication, we show that these proteins are important in maintaining genome integrity later in S phase and G2. hsk1 cells suffer increased rates of mitotic recombination and require recombination proteins for survival. Both hsk1 and dfp1 mutants are acutely sensitive to alkylation damage yet defective in induced mutagenesis. Hsk1 and Dfp1 are associated with the chromatin even after S phase, and normal response to MMS damage corre- lates with the maintenance of intact Dfp1 on chromatin. A screen for MMS-sensitive mutants identified a novel truncation allele, rad35 (dfp1-(1–519)), as well as alleles of other damage-associated genes. Although Hsk1–Dfp1 functions with the Swi1–Swi3 fork protection complex, it also acts independently of the FPC to promote DNA repair. We conclude that Hsk1–Dfp1 kinase functions post-initiation to maintain replica- tion fork stability, an activity potentially mediated by the C terminus of Dfp1. -

DNA Replication, Repair and Recombination

DNA replication, repair and recombination Asst. Prof. Dr. Altijana Hromic-Jahjefendic SS2020 DNA Genetic material Eukaryotes: in nucleus Prokaryotes: as plasmid Mitosis Division and duplication of somatic cells Production of two identical daughter cells from a single parent cell 4 stages: Prophase: The chromatin condenses into chromosomes. Each chromosome has duplicated to tow sister chromatids. The nuclear envelope breaks down. Metaphase: The chromosomes align at the equatorial plate and are held by microtubules attached to the mitotic spindle and to part of the centromere Anaphase: Centromeres divide and sister chromatids separate and move to corresponding poles Telophase: Daughter chromosomes arrive at the poles and the microtubules disappear. The nuclear envelope reappears DNA replication & recombination Reproduction (Replication) of a DNA-double helix - semiconservative fashion demonstrated by Meselson & Stahl by using 15N-labeled ammonium chloride in the growth medium heavy nitrogen label was incorporated in the DNA of the bacteria shifted to normal 14N-medium giving rise to density band between the “heavy” and the “light” band in the 1st generation In the 2nd generation, in addition to the hybrid band a light band appears which contains only 14N- DNA Synthesis of a new DNA strand nucleoside triphosphates are selected ability to form Watson-Crick base pairs to the corresponding position in the template strand DNA replication occurs at replication forks For replication - two parental DNA-strands must separate from -

Distribution of DNA Repair-Related Ests in Sugarcane

Genetics and Molecular Biology, 24 (1-4), 141-146 (2001) Distribution of DNA repair-related ESTs in sugarcane W.C. Lima, R. Medina-Silva, R.S. Galhardo and C.F.M. Menck* Abstract DNA repair pathways are necessary to maintain the proper genomic stability and ensure the survival of the organism, protecting it against the damaging effects of endogenous and exogenous agents. In this work, we made an analysis of the expression patterns of DNA repair-related genes in sugarcane, by determining the EST (expressed sequence tags) distribution in the different cDNA libraries of the SUCEST transcriptome project. Three different pathways - photoreactivation, base excision repair and nucleotide excision repair - were investigated by employing known DNA repair proteins as probes to identify homologous ESTs in sugarcane, by means of computer similarity search. The results showed that DNA repair genes may have differential expressions in tissues, depending on the pathway studied. These in silico data provide important clues on the potential variation of gene expression, to be confirmed by direct biochemical analysis. INTRODUCTION (The Arabidopsis Genome Initiative, 2000), have provided huge amounts of data that still need to be processed, in or- The genome of all living beings is constantly subject der to enable us to understand the physiological mecha- to damage generated by exogenous and endogenous fac- nisms of these organisms. This is the case of the DNA tors, reducing DNA stability and leading to an increase of repair pathways. Although repair and damage tolerance mutagenesis, cancer, cell death, senescence and other dele- mechanisms have been well described in bacteria, yeast, terious effects to organisms (de Laat et al., 1999). -

Redox Regulation of DNA Repair: Implications for Human Health and Cancer Therapeutic Development

ANTIOXIDANTS & REDOX SIGNALING Volume 12, Number 11, 2010 C OMPREHENSIVE INVITED REVIEW © Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. DOI: 10.1089/ ars.2009.2698 Redox Regulation of DNA Repair: Implications for Human Health and Cancer Therapeutic Development 2 2 Meihua Luo~ Hongzhen He, Mark R. Ke l ley ~ -3 and Millie M. Georgiadis .4 Abstract Red.ox reactions are known to regulate many important cellular processes. In this revievv, v.re focus on the role of redox regulation in DNA repair both in direct regulation of specific DNA repair proteins as well as indirect transcriptional regulation. A key player in the redox regulation of DNA repair is the base excision repair enzyme apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 (APEl) in its role as a redox factor. APEl is reduced by the general redox factor thioredoxin, and in turn reduces several important transcription factors that regulate expression of DNA repair proteins. Finally, we consider the potential for chemotherapeutic development through the modulation of APEl's redox activity and its impact on DNA repair. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 12, 1247-1269. l. Introduction 1248 II. DNA-Repair Pathways 1248 A. Mammalian d irect repair: 0 6-alkylguanine-DNA methyltransferase or 0 6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase 1249 B. Base-excision repair 1249 C. Nucleotide-excision repair 1249 D. Mismatch repair 1250 E. Nonhomologous DNA end-joining and homologous recombiJ.1ation 1250 ITT. General Redox Systems 1251 A. The thioredoxin system 1251 B. The glutaredoxin/glutathione system 1252 C. l~oles of general redox systems 1252 N. The Redox Activity of APEl 1252 A. Evolution of the redox function of APEl 1252 B. -

Homologous Recombination Rescues Ssdna Gaps Generated by Nucleotide Excision Repair and Reduced Translesion DNA Synthesis In

Homologous recombination rescues ssDNA gaps PNAS PLUS generated by nucleotide excision repair and reduced translesion DNA synthesis in yeast G2 cells Wenjian Ma, James W. Westmoreland, and Michael A. Resnick1 Chromosome Stability Group, Laboratory of Molecular Genetics, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health, Research Triangle Park, NC 27709 Edited by Philip C. Hanawalt, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, and approved June 21, 2013 (received for review January 26, 2013) Repair of DNA bulky lesions often involves multiple repair path- As we and others have reported, DSBs can be formed as ways such as nucleotide-excision repair, translesion DNA synthesis secondary products during processing of ssDNA lesions arising (TLS), and homologous recombination (HR). Although there is con- from agents such as methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) (8-10) at siderable information about individual pathways, little is known doses that result in closely opposed lesions. Because NER can about the complex interactions or extent to which damage in produce ssDNA gaps of ∼30 nt for a variety of bulky lesions, single strands, such as the damage generated by UV, can result in there is a greater likelihood of secondary generation of DSBs double-strand breaks (DSBs) and/or generate HR. We investigated than with base-excision repair, which generates short resection the consequences of UV-induced lesions in nonreplicating G2 cells regions. However, gap formation and subsequent refilling during of budding yeast. In contrast to WT cells, there was a dramatic NER are tightly coordinated, with repair synthesis starting after increase in ssDNA gaps for cells deficient in the TLS polymerases η incision on the 5′ side of the lesion (which precedes the 3′ in- (Rad30) and ζ (Rev3). -

Methyl-Directed Repair of DNA Base-Pair Mismatches in Vitro

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 80, pp. 4639-4643, August 1983 Biochemistry Methyl-directed repair of DNA base-pair mismatches in vitro (mutagenesis/gene conversion/DNA methylation) A.-LIEN Lu, SUSANNA CLARK, AND PAUL MODRICH Department of Biochemistry, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina 27710 Communicated by Robert L. Hill, April 18, 1983 ABSTRACT An assay has been developed that permits anal- system requires not only detection of base-pair mismatches but ysis of DNA mismatch repair in cell-free extracts of Escherichia a mechanism for discrimination of parental and newly synthe- coli The method relies on repair of heteroduplex molecules of fl sized strands as well. These authors suggested that the transient R229 DNA, which contain a base-pair mismatch within the single undermethylation of the newly synthesized strand might pro- EcoRI site of the molecule. As observed with mismatch hetero- vide the bias for such discrimination. Indeed, several lines of duplexes of A DNA [Pukila, P. J., Peterson, J., Herman, G., evidence indicate that dam methylation of d(G-A-T-C) se- Modrich, P. & Meselson, M. (1983) Genetics, in press], in vivo mis- quences functions in this respect. Thus, deficiency or over- match correction of fl heteroduplexes is directed by the state of production of this DNA methylase results in a mutator phe- dam methylation of d(G-A-T-C) sequences within the DNA du- notype (13, 14). In addition, genetic analysis has suggested that plex. Thus, the heteroduplex dam methylase participates in a pathway involving mutH, mutL, 5'-G-A-A-T-T-C and mutS function (15, 16). -

CLONING and CHARACTERIZATION of EXCISION Repam GENES

CLONING AND CHARACTERIZATION OF EXCISION REPAm GENES CLONING AND CHARACTERIZATION OF EXCISION REPAIR GENES KLONERING EN KARAKTERISERING VAN EXCISIE HERSTEL GENEN PROEFSCHRIFT TER VERKRIJGING VAN DE GRAAD VAN DOCTOR AAN DE ERASMUS UNIVERSITElT ROTTERDAM OP GEZAG VAN DE RECTOR MAGNIFICUS PROF. DR. P.W.C. AKKERMANS M.A. EN VOLGENS BESLUIT VAN HET COLLEGE VAN DEKANEN. DE OPEN BARE VERDEDIGING ZAL PLAATSVINDEN OP WOENSDAG 27 MAART 1996 OM 13:45 UUR DOOR PETRUS JOHANNES V AN DER SPEK GEBOREN TE DELFr PROMOTIECOMMISSIE Promotoren: Prof. Dr. D. Bootsma Prof. Dr. J.H.J. Hoeijmakers Overige leden: Prof. Dr. LA. Grootegoed Prof. Dr. D. Lindhout Prof. Dr. Ir. A.A. van Zeeland The studies described in this thesis were carried out in the Medical Genetics Centre South-West Netherlands at the department of Cell Biology and Genetics Erasmus University Rotterdam. This project was financially supported by the Medical Genetics Centre and the Dutch Cancer Society. The printing of this thesis was financially supported by: Ames B. V., Autron B. V., Bio Rad Laboratories B.V., Biozym B.V., Eurogentec N.V., Het Kasteel van Rhoon, Pharmacia B.V., Schleicher & Schuell Nederland B.V. and Thieme's Echte Thee. Front cover Three dimensional representation of the protein structure of ubiquitin. In blue (identical) and in orange (similar) residues shared by the NER enzyme RAD23 The similar spacefilling model indicates the homologous residues of the conserved core. Molecular modeling and image processing was performed at the National Institutes of Health's division of computer research and technology, Bethesda. USA. Illustrations Mirko Kuit Printing Drukkerij Haveka B.V., Alblasserdam The known is finite, the unknown infinite; intellectually we stand on an island in the midst of an illimitable ocean of inexplicability.