Re-Imagining Eros: Dare to Fall in Love with God Christopher Peter Lindstrom George Fox University, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Faraone Ancient Greek Love Magic.Pdf

Ancient Greek Love Magic Ancient Greek Love Magic Christopher A. Faraone Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England Copyright © 1999 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Second printing, 2001 First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 2001 library of congress cataloging-in-publication data Faraone, Christopher A. Ancient Greek love magic / Christopher A. Faraone. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN 0-674-03320-5 (cloth) ISBN 0-674-00696-8 (pbk.) 1. Magic, Greek. 2. Love—Miscellanea—History. I. Title. BF1591.F37 1999 133.4Ј42Ј0938—dc21 99-10676 For Susan sê gfir Ãn seautá tfi f©rmaka Æxeiv (Plutarch Moralia 141c) Contents Preface ix 1 Introduction 1 1.1 The Ubiquity of Love Magic 5 1.2 Definitions and a New Taxonomy 15 1.3 The Advantages of a Synchronic and Comparative Approach 30 2 Spells for Inducing Uncontrollable Passion (Ero%s) 41 2.1 If ErÃs Is a Disease, Then Erotic Magic Is a Curse 43 2.2 Jason’s Iunx and the Greek Tradition of Ago%ge% Spells 55 2.3 Apples for Atalanta and Pomegranates for Persephone 69 2.4 The Transitory Violence of Greek Weddings and Erotic Magic 78 3 Spells for Inducing Affection (Philia) 96 3.1 Aphrodite’s Kestos Himas and Other Amuletic Love Charms 97 3.2 Deianeira’s Mistake: The Confusion of Love Potions and Poisons 110 3.3 Narcotics and Knotted Cords: The Subversive Cast of Philia Magic 119 4 Some Final Thoughts on History, Gender, and Desire 132 4.1 From Aphrodite to the Restless -

Understanding Marriage and Families Across Time and Place M01 ESHL8740 12 SE C01.QXD 9/14/09 5:28 PM Page 3

M01_ESHL8740_12_SE_C01.QXD 9/14/09 5:28 PM Page 2 part I Understanding Marriage and Families across Time and Place M01_ESHL8740_12_SE_C01.QXD 9/14/09 5:28 PM Page 3 chapter 1 Defining the Family Institutional and Disciplinary Concerns Case Example What Is a Family? Is There a Universal Standard? What Do Contemporary Families Look Like? Ross and Janet have been married more than forty-seven years. They have two chil- dren, a daughter-in-law and a son-in-law, and four grandsons. Few would dispute the notion that all these members are part of a common kinship group because all are related by birth or marriage. The three couples involved each got engaged, made a public announcement of their wedding plans, got married in a religious ceremony, and moved to separate residences, and each female accepted her husband’s last name. Few would question that each of these groups of couples with their children constitutes a family, although a question remains as to whether they are a single family unit or multiple family units. More difficult to classify are the families of Vernon and Jeanne and their chil- dren. Married for more than twenty years, Vernon and Jeanne had four children whom have had vastly different family experiences. Their oldest son, John, moved into a new addition to his parents’ house when he was married and continues to live there with his wife and three children. Are John, his wife, and his children a separate family unit, or are they part of Vernon and Jeanne’s family unit? The second child, Sonia, pursued a career in marketing and never married. -

Lesbian and Gay Music

Revista Eletrônica de Musicologia Volume VII – Dezembro de 2002 Lesbian and Gay Music by Philip Brett and Elizabeth Wood the unexpurgated full-length original of the New Grove II article, edited by Carlos Palombini A record, in both historical documentation and biographical reclamation, of the struggles and sensi- bilities of homosexual people of the West that came out in their music, and of the [undoubted but unacknowledged] contribution of homosexual men and women to the music profession. In broader terms, a special perspective from which Western music of all kinds can be heard and critiqued. I. INTRODUCTION TO THE ORIGINAL VERSION 1 II. (HOMO)SEXUALIT Y AND MUSICALIT Y 2 III. MUSIC AND THE LESBIAN AND GAY MOVEMENT 7 IV. MUSICAL THEATRE, JAZZ AND POPULAR MUSIC 10 V. MUSIC AND THE AIDS/HIV CRISIS 13 VI. DEVELOPMENTS IN THE 1990S 14 VII. DIVAS AND DISCOS 16 VIII. ANTHROPOLOGY AND HISTORY 19 IX. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 24 X. EDITOR’S NOTES 24 XI. DISCOGRAPHY 25 XII. BIBLIOGRAPHY 25 I. INTRODUCTION TO THE ORIGINAL VERSION 1 What Grove printed under ‘Gay and Lesbian Music’ was not entirely what we intended, from the title on. Since we were allotted only two 2500 words and wrote almost five times as much, we inevitably expected cuts. These came not as we feared in the more theoretical sections, but in certain other tar- geted areas: names, popular music, and the role of women. Though some living musicians were allowed in, all those thought to be uncomfortable about their sexual orientation’s being known were excised, beginning with Boulez. -

Metamorphosis of Love: Eros As Agent in Revolutionary and Post-Revolutionary France" (2017)

University of Central Florida STARS Honors Undergraduate Theses UCF Theses and Dissertations 2017 Metamorphosis of Love: Eros as Agent in Revolutionary and Post- Revolutionary France Jennifer N. Laffick University of Central Florida Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the UCF Theses and Dissertations at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Laffick, Jennifer N., "Metamorphosis of Love: Eros as Agent in Revolutionary and Post-Revolutionary France" (2017). Honors Undergraduate Theses. 195. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses/195 METAMORPHOSIS OF LOVE: EROS AS AGENT IN REVOLUTIONARY AND POST-REVOLUTIONARY FRANCE by JENNIFER N. LAFFICK A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Major Program in Art History in the College of Arts and Humanities and in The Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term, 2017 Thesis Chair: Dr. Margaret Zaho ABSTRACT This thesis chronicles the god of love, Eros, and the shifts of function and imagery associated with him. Between the French Revolution and the fall of Napoleon Eros’s portrayals shift from the Rococo’s mischievous infant revealer of love to a beautiful adolescent in love, more specifically, in love with Psyche. In the 1790s, with Neoclassicism in full force, the literature of antiquity was widely read by the upper class. -

Hubbard on Davidson-Lear.Pdf

CJ ONLINE 2009.11.03 * A slightly different version of this review was published previously in February 2009 on the Hist-Sex list of H-Net. http://h-net.msu.edu/cgi-bin/logbrowse.pl?trx=vx&list=h-hist sex&month=0902&week=b&msg=Ug%2bYuljwHAbsmjyw%2bhMX hQ&user=&pw= The Greeks and Greek Love: A Radical Reappraisal of Homosexuality in Ancient Greece. By JAMES DAVIDSON. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2007. Pp. xxii + 634. Cloth, $42.00. ISBN 978–0–297–81997– 4. Images of Ancient Greek Pederasty: Boys were their Gods. By ANDREW LEAR AND EVA CANTARELLA. London and New York: Rout- ledge, 2008. Pp. xviii + 262. Cloth, $115.00. ISBN 978–0–415–22367–6. Study of Greek same-sex relations since Sir Kenneth Dover’s influen- tial Greek Homosexuality (London, 1978) has been dominated by a hi- erarchical understanding of the pederastic relations assumed to be normative between older, sexually and emotionally active “lovers” and younger, sexually and emotionally passive “beloveds.” Michel Foucault’s subsequent History of Sexuality: Vol. 2, The Use of Pleasure (New York, 1986) was heavily influenced by Dover’s collection of evidence and concretized these roles into formalized “sexual proto- cols.” Self-consciously invoking Foucault was David Halperin’s One Hundred Years of Homosexuality (London, 1990), which envisioned phallic penetration as a trope for the asymmetrical political em- powerment of adult citizen males over “women, boys, foreigners, and slaves—all of them persons who do not enjoy the same legal and political rights and privileges that he does” (Halperin, p. 30). -

Psychoanalytic Conceptions of Marriage and Marital Relationships 381 Been Discussing, Since These Figures Are Able to Reanimate Pictures of Their Mother Or Father

UNIVERSITY OF NIŠ The scientific journal FACTA UNIVERSITATIS Series: Philosophy and Sociology Vol.2, No 7, 2000 pp. 379 - 389 Editor of series: Gligorije Zaječaranović Address: Univerzitetski trg 2, 18000 Niš, YU Tel: +381 18 547-095, Fax: +381 18 547-950 PSYCHOANALYTIC CONCEPTIONS OF MARRIAGE AND MARITAL RELATIONSHIPS UDC 159.964.28+173.1+340.61 Zorica Marković University of Niš, Faculty of Philosophy, Niš, Yugoslavia Abstract. This work disclusses marital types and merital relationships as by several psychoanalysts: Sigmund Freud, Annie Reich, Helene Deutch, Knight Aldrich and Bela Mittelman. It analyzes kinds of relations hips, dynamics of interaction and inner mechanisms of interaction.Comparing marital types of the mentioned authors it can be seen that there is agreement among them and that they mainly represent further elaboration and "topic variation" of the basic marital types which are discussed by Sigmund Freud: anaclictic and narcissistic.Also, it can be concluded that all analysed marital types possess several common characteristics: 1. they are defined by relationships in childhood with parents or other important persons with whom a child was in touch; 2. dynamics of partner relationships is defined by unconscious motives; 3. same kinds of relationships and same type of partner selection a person repeats in all further attempts in spite of the fact that it does not give satisfactory results. Key words: psychoanalysis, marriage, partner, choice, relationships According to Si gmund Fr e ud , the founder of psychoanalysis, marital partner choice, as well as marital relationships, are defined much before marriage was concluded. Relationship with marital partner is determined by relationships with parents and important persons in one's childhood. -

Outline of the Book I. the Glorious Position of the Body of Christ (1:1-3:21) A

EPHESIANS.43 P a g e | 1 Outline of the Book I. The Glorious Position of the Body of Christ (1:1-3:21) A. Greetings (1:1-2) B. The Believer’s “Astounding Station” in Christ, to the praise of His glory (1:3-14) --- The Grace of the Father (1:3-6) --- The Grace of the Son (1:7-12) --- The Grace of the Spirit (1:13-14) C. Paul’s Motivated Prayer & Praise 1 (1:15-23) D. The Believer’s Collective Transport (2:1-10) --- Dead in Trespasses (2:1-3) --- Made Alive with Christ (2:4-10) E. Unified in Christ (2:11-22) --- Brought Near by the Blood (2:11-13) --- The Cross Creates One New Man (2:14-18) a. By Abolishing the Law (2:14-15) b. By Reconciling Us to the Father (2:16-18) --- Fellow Citizens in the Household of God (2:19-22) F. The Mystery of the Gospel (3:1-3:13) --- Prayer Interrupted (3:1) --- The Dispensation of God’s Grace (3:2-5) --- The Gentiles are Fellow Heirs (3:6-13) G. Paul’s Motivated Prayer & Praise 2 (3:14-21) II. The Glorious Practice of the Body of Christ (4:1-6:24) A. A Worthy Walk that Promotes Unity (4:1-6) B. Measures of Grace for Equipping the Body (4:7-16) C. Exhortation to Put on the New Self (4:17-24) D. Conduct that Benefits the Body (4:25-32) E. Serious Calling/Serious Consequences (5:1-21) F. Serious Calling Explained (5:22-6:20) --- The Example of Marriage (5:22-33) --- Parental Relationships (6:1-4) --- Occupational Relationships (6:5-9) --- Spiritual Opposition (6:10-20) G. -

Agape and Eros: a Critique of Nygren

AGAPE AND EROS A. S. DEWDNEY O one can read Bishop Nygren's great work Agape and Eros without Ngratitude and much delight. This is one of those monumental works of which only a very few are produced in any generation and which help to clarify and mould the thinking of men everywhere. Agape and Eros are words which are here to stay in our theological vocabulary because they express the two great motifs underlying the more inclusive word "love". They enable us to distinguish these elements and to handle them with more precision and understanding of what they mean. All preachers and theologians have suffered in the past in attempting to clarify what is involved in the Christian idea of love, whether it is the love of God to man, of man to God, of man to his neighbour, or the meaning and place to be given to self-love. We now have a clear word for two aspects of what are commonly called love, and for this we must be forever indebted to Bishop Nygren's clear and searching analysis. He has helped us to resolve much of this ambiguity. Nygren distinguishes two types of love. One is the love of desire. It is the love which values and seeks to possess some good in its object. It is motivated by that good. We love that which is good, that is, that which is good for us. Such a love is self-centred. However lofty the object on which it places its love, essentially it sees that object as a good to be possessed. -

Title 30. Husband and Wife Chapter 1 Marriage

Utah Code Title 30. Husband and Wife Chapter 1 Marriage 30-1-1 Incestuous marriages void. (1) The following marriages are incestuous and void from the beginning, whether the relationship is legitimate or illegitimate: (a) marriages between parents and children; (b) marriages between ancestors and descendants of every degree; (c) marriages between siblings of the half as well as the whole blood; (d) marriages between: (i) uncles and nieces or nephews; or (ii) aunts and nieces or nephews; (e) marriages between first cousins, except as provided in Subsection (2); or (f) marriages between any individuals related to each other within and not including the fifth degree of consanguinity computed according to the rules of the civil law, except as provided in Subsection (2). (2) First cousins may marry under the following circumstances: (a) both parties are 65 years of age or older; or (b) if both parties are 55 years of age or older, upon a finding by the district court, located in the district in which either party resides, that either party is unable to reproduce. Amended by Chapter 317, 2019 General Session 30-1-2 Marriages prohibited and void. (1) The following marriages are prohibited and declared void: (a) when there is a spouse living, from whom the individual marrying has not been divorced; (b) except as provided in Subsection (2), when an applicant is under 18 years old; and (c) between a divorced individual and any individual other than the one from whom the divorce was secured until the divorce decree becomes absolute, and, if an appeal is taken, until after the affirmance of the decree. -

Benedict XVI's Deus Caritas Est Gregoriana, 1973), 60

------I ::c ~ r'T""'1 ~.~ s: 0 ~ lJ r-- -c::;, ~~ ~:J rn_ :::t:> g, en -=z t:::::::J rT""'I OPJ~ t:::::::J ~ c::: :::t:> ~ :::t:> ~ (D rT""'I ~o ::c ~ ~ ~ rn ~ t:I::I ~ c~o.. i- 0 C? -c::: =z ~ 0 :::t:> ~ 80m ~ A =z r'T""'1 ~ en :::::c::J ~~rt =zr'T""'1 ~~ C"""':) o..~. r'T""'1 n en To the church, university, and people of Padua, especially Renzo Pegomro and the Fondazione Lanza Founded in 1970, Orbis Books endeavors to publish works that enlighten the mind, nourish the spirit, and challenge the conscience. The publishing arm of the Maryknoll Fathers and Brothers, Orbis seeks to explore the global dimensions of the Christian faith and mission, to invite dialogue with diverse cultures and religious traditions, and to serve the cause of reconciliation and peace. The books published reflect the views of their authors and do not represent the official position of the Maryknoll Society. To learn more about Maryknoll and Orbis Books, please visit our website at www.maryknoll.org. Copyright © 2008 by Linda Hogan. Published by Orbis Books, Maryknoll, New York 10545-0308. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any in formation storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Queries regarding rights and permissions should be addressed to Orbis Books, P.O. Box 308, Maryknoll, NY 10545-0308. Manufactured in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Applied ethics in a world church: the Padua conference / Linda Hogan, editor. -

840:240 Love As Ethic and Idea Fall, 2014 Tth 1:10-2:30 HH-B3, CAC

840:240 Love as Ethic and Idea Fall, 2014 TTh 1:10-2:30 HH-B3, CAC James T. Johnson Loree 102, DC; 848-932-6820; [email protected] Shape of the course: This course is concerned with how love, as a theological idea and as the source of a religious ethic, has developed in western religious tradition from biblical Israel and classical Greece to the present, with emphasis on Christian thought and western culture as influenced by it. We will examine the ethic and idea of love in five historical periods (Parts I-V below) to try to understand how love was conceived and what influence on conduct this implied in each period. There will be three tests in the form of what I call "directed papers": writing assignments on the ideas covered in the readings and class lectures. You will get the assignment for the first paper on Thursday, February 14, write it at home, and turn it in a week later on February 21. The second assignment will be made on March 28 and will be due on April 4. The final paper assignment will be given out the last class day for this course, May 2; it is due during the period the final exam for this course is scheduled. These three papers will be weighted equally. Regular class attendance and participation are important. Accordingly, the final grade will reflect excess absences. After the first week, when people are still getting their schedules finalized, attendance will be taken each class meeting. After that week we will have 26 days of class in this course. -

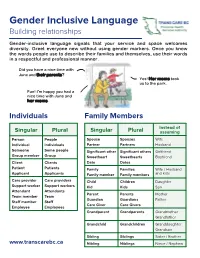

Gender Inclusive Language Building Relationships

Gender Inclusive Language Building relationships Gender-inclusive language signals that your service and space welcomes diversity. Greet everyone new without using gender markers. Once you know the words people use to describe their families and themselves, use their words in a respectful and professional manner. Did you have a nice time with June and their parents? Yes! Her moms took us to the park. Fun! I'm happy you had a nice time with June and her moms. Individuals Family Members Instead of Singular Plural Singular Plural assuming Person People Spouse Spouses Wife Individual Individuals Partner Partners Husband Someone Some people Significant other Significant others Girlfriend Group member Group Sweetheart Sweethearts Boyfriend Client Clients Date Dates Patient Patients Family Families Wife / Husband Applicant Applicants Family member Family members and kids Care provider Care providers Child Children Daughter Support worker Support workers Kid Kids Son Attendant Attendants Parent Parents Mother Team member Team Guardian Guardians Father Staff member Staff Care Giver Care Givers Employee Employees Grandparent Grandparents Grandmother Grandfather Grandchild Grandchildren Granddaughter Grandson Sibling Siblings Sister / Brother www.transcarebc.ca Nibling Niblings Niece / Nephew ii Pronouns (using they in the singular) If you are in a setting where your interactions with people are brief, you may not have time to get to know the person. Using the singular they in these situations can help to avoid pronoun mistakes. subject They They are waiting at the door. object Them The form is for them. possessive Their Their parents will pick them up at 3pm. adjective possessive Theirs They said the wheelchair is not theirs.