Unit 40 Case Study: Bombay*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History, Culture and the Indian City

This page intentionally left blank History, Culture and the Indian City Rajnarayan Chandavarkar’s sudden death in 2006 was a massive blow to the study of the history of modern India, and the public tributes that have appeared since have confirmed an unusually sharp sense of loss. Dr Chandavarkar left behind a very subsantial collection of unpublished lectures, papers and articles, and these have now been assembled and edited by Jennifer Davis, Gordon Johnson and David Washbrook. The appearance of this collection will be widely welcomed by large numbers of scholars of Indian history, politics and society. The essays centre around three major themes: the city of Bombay, Indian politics and society, and Indian historiography. Each manifests Dr Chandavarkar’s hallmark historical powers of imaginative empirical richness, analytic acuity and expository elegance, and the volume as a whole will make both a major contribution to the historiography of modern India, and a worthy memorial to a very considerable scholar. History, Culture and the Indian City Essays by Rajnarayan Chandavarkar CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo, Delhi, Dubai, Tokyo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521768719 © Rajnarayan Chandavarkar 2009 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provision of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published in print format 2009 ISBN-13 978-0-511-64140-4 eBook (NetLibrary) ISBN-13 978-0-521-76871-9 Hardback Cambridge University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of urls for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this publication, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. -

101 3 Contributions of Walter Ducat and Vasudev Kanitkar This

3 Contributions of Walter Ducat and Vasudev Kanitkar 7KLV GLVFRXUVH RQ ZRUNV FDUULHG RXW E\ &RORQHO:DOWHU'XFDW 5( DQG9DVXGHY %DSXML Kanitkar in Deccan region enhance on their graph of work they executed and collaborative landmark at the summit of their career they produced in Poona. There is an attempt to establish DQGXQYHLO:DOWHU'XFDW¶VFRQWULEXWLRQLQWKHGHYHORSPHQWRIERWKELJJHUDQGVPDOOVFDOHWRZQVLQ Deccan region such as Pune, Kolhapur, Ahmadnagar, Ahmedabad, Gokak and so on. Probably this GRFXPHQWDWLRQDQGDQDO\VLVRI:DOWHU'XFDW¶VVHUYLFHLQWKHUHJLRQWU\WRSHUFHLYHKLVLQYROYHPHQW in architectural developments in the late nineteenth century at various levels as engineer, urban designer, town planner, irrigation expert and designer of minor projects those are milestones in colonial urban landscapes. This discussion will perhaps support his collaborative works with different agencies and local contractors in the process of actual implementation of several projects. Different social forces such as local intellectuals and reformists during revolts in 19th century against the colonial architectural expansions lead to a different manifestation in the perceptible form. Language, climate, cultural variations turn out to be advantages and hurdles at the same time for WKHQHZ³WHFKQRFUDWLFUHJLPH´2QWKHRWKHUKDQGVHWSDUDPHWHUVRIPDQXDOVWUHDWLVHSURIHVVLRQDO papers and major involvement of local artisans and contractors probably tried to contribute to the DUFKLWHFWXUDOYRFDEXODU\ZLWKWKHLUPRGL¿HG,QGLJHQRXVVROXWLRQVLQORFDOFRQWH[W7KLVGLVFXVVLRQ ZLOOSUREDEO\WU\WRHODERUDWHPRUHRQ:DOWHU'XFDW¶VZRUNEHLQJD³SURGXFWRI$GGLVFRPEH´273 -

Letter from Bombay

40 THE NATIONAL MEDICAL JOURNAL OF INDIA VOL. 8, NO.1, 1995 Letter from Bombay THE ONE HUNDRED AND FIFfIETH ANNIVERSARY Sohan Lal Bhatia (the first Indian to be appointed Prinicipal OF THE GRANT MEDICAL COLLEGE AND SIR J. J. of the Grant Medical College), Jivraj Mehta (Mahatma GROUP OF HOSPITALS Gandhi's personal physician) and Raghavendra Row (who When Sir Robert Grant took over the reins as Governor suggested that leprosy be treated with a vaccine prepared of Bombay in 1834, he was struck by the poor state of from the tubercle bacillus). There were also V. N. Shirodkar public health throughout the Presidency. At his instance, (best known for his innovative operations in obstetrics and Dr Charles Morehead and the Bombay Medical and Physical gynaecology) and Rustom N. Cooper (who did pioneering Society conducted a survey throughout the districts of the work on blood transfusion as well as on surgery for diseases then Bombay Presidency on the state of health, facilities for of the nervous system). medical care and education of practising native doctors. On More recently, two Noshirs-Drs Noshir Antia (who has the basis of this exemplary survey, it was decided to set up done so much to rehabilitate patients with leprosy) and a medical college for Indian citizens with the intention of Noshir Wadia (the neurologist) have brought more fame to sending them out as full-fledged doctors. these institutions. The proposal encountered stiff opposition. A medical Factors favouring excellence at these institutions school had floundered and collapsed within recent memory. Among the arguments put forth was the claim that natives All of us, however, who love the Grant Medical College did not possess the faculties and application necessary for and the J. -

Province Holidays!! Fr

Vol. 75 No. 4 - 5 April – May 2021 3 General Curia Province Holidays!! Fr. General has appointed Cool weather, scenic surroundings, a relaxed Fr. K.C. Stephen the new Provincial of Dumka- daily schedule … and … good company. Raiganj province Fr. A. Nirmal Raj (DUM) the new Rector of St. Stanislaus Villa, Lonavala. Vidya Jyoti, Delhi Mon, 26 Apr to Mon, 03 May Fr. Zbigniew Leczkowski the new Provincial of Greater Poland and Mazovia A bus has been arranged as follows - Mon, 26 April. Mumbai to Lonavala. Leaving St. Peter’s Bandra at 6:30 am. Fr. Provincial’s schedule: April-May 2021 - Mon, 3 May. Lonavala to Mumbai 19 April Province Congregation Province Consult 24 April XLRI GB meeting 12-15 May Praful’s Ordination. Jashpur 16-31 May Annual Retreat, Break Notice: The Congregation for Catholic Education, Rome has approved Fr. Konrad Noronha for the grade of “Professor Ordinarius” in the Faculty of Theology, Jnana Deepa Pune. Hearty Congratulations to you Konrad! If you can't come for all the days, do drop in for even a day or two. A reminder Contact: Gerard Rodricks 9223262524 Priestly Ordination of Praful Ekka: Friday, 14 May 2021 at 6:30 am at Ajdha, Jashpur,CG Flipbook on Br. Leonhard Zimmer SJ Mr. Ajit Lokhande has written a booklet on Thanksgiving Eucharist: Saturday, 15 May 2021 Br. Zimmer, the Apostle of the Kathkaris. at 7:00 am at Ganjhar, Jashpur, CG. Here is the link to this flipbook. https://online.fliphtml5.com/lbnxr/qdhi/ Contact Praful for further details Thank you Ajit. -

Why the Portuguese Told the British That Brazil Was Just a Hop, Skip and Jump Away from Bombay

URMI CHANDA-VAZ K Indologist cultureexpress.in Why the Portuguese told the British that Brazil was just a hop, skip and jump away from Bombay An exhibition of woodcuts and lithographs tells the city's history in 46 prints Mumbai is a fast-paced city in more ways than one. With the daily movement of its millions, its cultural and geographical landscape are quickly morphed. One place to witness the story of its rapidly changing colours is the Prints Gallery at the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya or CSMVS, at Fort, Mumbai. The exhibition therein is titled Bombay to Mumbai: Door of the East with its Face to the West. While the gallery opened in 2015, its catalogue was released only in March, by Dr Anne Buddle, the Collections Advisor of National Galleries of Scotland. The collection in this gallery is curated by Pauline Rohatgi and Dr Pheroza Godrej, both well known for their work in art and local history. Together, they have put together a sizable collection of prints, which are veritable historical treasures. After years of curating, exhibiting and publishing them, Rohatgi and Godrej decided to give the prints on a long term lease, so they could be seen by a wider audience and maintained by the Gallery. “The idea came about in 2007 or 2008, when the CSMVS had its first International exhibition based on the Indian life and landscape,” said Dr Godrej. The collection was put together in association with Sabyasachi Mukherjee, the director general of CSMVS, who promised to make permanent space in the museum for the collection. -

Study of Housing Typologies in Mumbai

HOUSING TYPOLOGIES IN MUMBAI CRIT May 2007 HOUSING TYPOLOGIES IN MUMBAI CRIT May 2007 1 Research Team Prasad Shetty Rupali Gupte Ritesh Patil Aparna Parikh Neha Sabnis Benita Menezes CRIT would like to thank the Urban Age Programme, London School of Economics for providing financial support for this project. CRIT would also like to thank Yogita Lokhande, Chitra Venkatramani and Ubaid Ansari for their contributions in this project. Front Cover: Street in Fanaswadi, Inner City Area of Mumbai 2 Study of House Types in Mumbai As any other urban area with a dense history, Mumbai has several kinds of house types developed over various stages of its history. However, unlike in the case of many other cities all over the world, each one of its residences is invariably occupied by the city dwellers of this metropolis. Nothing is wasted or abandoned as old, unfitting, or dilapidated in this colossal economy. The housing condition of today’s Mumbai can be discussed through its various kinds of housing types, which form a bulk of the city’s lived spaces This study is intended towards making a compilation of house types in (and wherever relevant; around) Mumbai. House Type here means a generic representative form that helps in conceptualising all the houses that such a form represents. It is not a specific design executed by any important architect, which would be a-typical or unique. It is a form that is generated in a specific cultural epoch/condition. This generic ‘type’ can further have several variations and could be interestingly designed /interpreted / transformed by architects. -

Bombay Novels

Bombay Novels: Some Insights in Spatial Criticism Bombay Novels: Some Insights in Spatial Criticism By Mamta Mantri With a Foreword by Amrit Gangar Bombay Novels: Some Insights in Spatial Criticism By Mamta Mantri This book first published 2019 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2019 by Mamta Mantri All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-2390-X ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-2390-6 For Vinay and Rajesh TABLE OFCONTENTS Acknowledgements ......................................................................... ix Foreword ......................................................................................... xi Introduction ................................................................................. xxvi Chapter One ...................................................................................... 1 The Contours of a City What is a City? The City in Western Philosophy and Polity The City in Western Literature The City in India Chapter Two ................................................................................... 30 Locating the City in Spatial Criticism The History of Spatial Criticism Space and Time Space, -

Durable Housing Alternative for Dharavi

2018 Durable housing alternative for Dharavi Imre Lokhorst and Floriaan Troost V6 Isendoorn College 20-12-2018 Page of content Summary 4 Introduction 5 Aim 6 Sub-aims 6 Hypothesis 6 List of requirements 7 Theory 8 Geographical context 8 Location 8 Population 8 Climate 9 Flooding risks 12 The effect of the climate on the houses in Dharavi 13 Economic situation 14 Social situation 15 Employment opportunities 15 Education 15 Education in Dharavi 16 Cultural situation 17 Language 17 Religion 17 Historical context Mumbai 18 History of Mumbai 18 Slum development in general 18 History of the developments in Dharavi 19 Political situation 20 FSI 21 Expensive ground 22 Political parties and Dharavi 22 The thoughts of Mumbai’s inhabitants about Dharavi 22 Current houses in Dharavi 23 Current living conditions in Dharavi 24 Theory of the design 25 Construction 25 1 Materials 25 Design 27 30 Foundation 32 Materials 32 Design 33 Walls 34 Materials 34 Design 36 Roof 40 Materials 40 Design 41 Water system 42 Materials 42 Design 42 Floors 43 Materials 43 Design 43 How we improve the living conditions with our design 43 Possible organizations we could approach 44 Financial plan 45 Costs 45 Experimental section 46 Materials and equipment’s 46 Materials for the construction 46 Materials for the foundation 46 Materials for the walls 47 Materials for the roof 47 Method 47 Method for the construction 47 Method for the foundation 58 Method for the walls 60 Method for the roof 60 Results 62 Observations 62 Construction 62 2 Numbers 65 Construction 65 Foundation 66 Roof 70 Conclusion 72 Answer to the main research question 72 Answers to the sub questions 72 The design 73 Discussion 73 Hypotheses-check 74 Did we meet the requirements 74 Estimation of magnitude of the errors 74 Continuation research 75 References 75 3 Summary This research paper is about a durable housing alternative for the slums in Dharavi. -

Culture on Environment: Rajya Sabha 2013-14

Culture on Environment: Rajya Sabha 2013-14 Q. No. Q. Type Date Ans by Members Title of the Questions Subject Specific Political State Ministry Party Representati ve Nomination of Majuli Shri Birendra Prasad Island as World Heritage Environmental 944 Unstarred 14.08.2013 Culture Baishya Site Conservation AGP Assam Protected monuments in Environmental 945 Unstarred 14.08.2013 Culture Shri D.P. Tripathi Maharashtra Conservation NCP Maharashtra Shri Rajeev Monuments of national Environmental *209 Starred 05.02.2014 Culture Chandrasekhar importance in Karnataka Conservation IND. Karnataka Dr. Chandan Mitra John Marshall guidelines for preservation of Environmental Madhya 1569 Unstarred 05.02.2014 Culture monuments Conservation BJP Pradesh Pollution Shri Birendra Prasad Majuli Island for World Environmental 1572 Unstarred 05.02.2014 Culture Baishya Heritage list Conservation AGP Assam Monuments and heritage Environmental Madhya 2203 Unstarred 12.02.2014 Culture Dr. Najma A. Heptulla sites in M.P. Conservation BJP Pradesh NOMINATION OF MAJULI ISLAND AS WORLD HERITAGE SITE 14th August, 2013 RSQ 944 SHRI BIRENDRA PRASAD BAISHYA Will the Minister of CULTURE be pleased to state: (a) the present status of the nomination dossier submitted for inscription of Majuli Island as World Heritage Site; (b) whether Government has fulfilled all requirements for completion of the nomination process in respect of Majuli Island; (c) if so, the details thereof and date-wise response made on all queries of UNESCO; and (d) by when the island is likely to be finally inscribed as a World Heritage Site? MINISTER OF CULTURE (SHRIMATI CHANDRESH KUMARI KATOCH) (a) (b) The revised nomination dossier on Majuli Island submitted to World Heritage Centre (WHC) in January, 2012 needs further modification in view of revision of Operational Guidelines. -

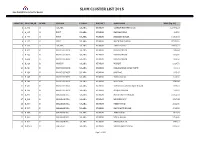

List of Slum Cluster 2015

SLUM CLUSTER LIST 2015 Slum Rehabilitation Authority, Mumbai OBJECTID CLUSTER_ID WARD VILLAGE TALUKA DISTRICT SLUM NAME AREA (Sq. M.) 1 A_001 A COLABA COLABA MUMBAI GANESH MURTHI NAGAR 120771.23 2 A_005 A FORT COLABA MUMBAI BANGALIPURA 318.50 3 A_006 A FORT COLABA MUMBAI NARIMAN NAGAR 14315.98 4 A_007 A FORT COLABA MUMBAI MACHIMAR NAGAR 37181.09 5 A_009 A COLABA COLABA MUMBAI GEETA NAGAR 26501.21 6 B_021 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI DANA BANDAR 939.53 7 B_022 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI DANA BANDAR 1292.90 8 B_023 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI DANA BANDAR 318.67 9 B_029 B MANDVI COLABA MUMBAI MANDVI 1324.71 10 B_034 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI NALABANDAR JOPAD PATTI 600.14 11 B_039 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI JHOPDAS 908.47 12 B_045 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI INDRA NAGAR 1026.09 13 B_046 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI MAZGAON 1541.46 14 B_047 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI SUBHASHCHANDRA BOSE NAGAR 848.16 15 B_049 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI MASJID BANDAR 277.27 16 D_001 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI MATA PARVATI NAGAR 21352.02 17 D_003 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI BRANHDHARY 1597.88 18 D_006 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI PREM NAGAR 3211.09 19 D_007 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI NAVSHANTI NAGAR 4013.82 20 D_008 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI ASHA NAGAR 1899.04 21 D_009 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI SIMLA NAGAR 9706.69 22 D_010 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI SHIVAJI NAGAR 1841.12 23 D_015A D GIRGAUM COLABA MUMBAI SIDHDHARTH NAGAR 2189.50 Page 1 of 101 SLUM CLUSTER LIST 2015 Slum Rehabilitation Authority, Mumbai OBJECTID CLUSTER_ID WARD VILLAGE TALUKA DISTRICT SLUM NAME AREA (Sq. -

E Ward – 65 Open Spaces

E Ward – 65 Open Spaces Sr. Open Space Location Reservation Area As Per No As Per DP DP 1991 1991 (sq.mt.) 1 Shoukat Ali PG Sheikh Hafizuddin Marg, Mumbai PG 608 – 8 2 Joseph Baptista Garden Mazgaon Hill road, Dockyard G 51,838 road, Mumbai – 400100 3 Mohd. Hussain PG YMCA road, Madanpura Mumbai RG 10,214 - 8 4 P.T.Mane Udyan Mirza Galib Road, Nagpada RG 5813 Junction, Mumbai - 8 5 Mastan Tank PG Dimtimkar Marg, Nagpada PG 2367 junction, Mumbai - 8 6 Dayan Baug Playground Khandiya Street, (Undariya Marg), RG 2100 Nagpada, Mumbai - 8 7 V.R. Tullah Kridangan 12th Lane, Kamathipura, Mumbai RG 1684 - 8 8 Nawab Ayaz Ali Tank Road, Mazgaon, Mumbai-10 RG 1506 9 Bachookhan Municipal PG 3rd peer Khan, Nagpada, Mumbai PG 1400 – 8 10 Nana Nani Park Gunpowder lane, Dockyard Road, RG 1083 Mumbai - 8 11 P.G. at Botliboy Compound Ghodapdeo, Anant Pawar Marg, PG 900 Mumbai -33 12 Verimalji Makaji Bohra R.G. 10th Lane, Kamathipura RG 900 Nagpada, Mumbai 13 Suresh Vithoba Acharekar CTS No.804, 805, 806, T.D. Gully, RG 730 Maidan Ambedkar Rd., Chinchpokali, Mumbai 14 Abdul Rehman Sufi Maidan Maulana Azad Rd., Madanpura, PG 600 Mumbai – 8 15 BMC Chawl opp. Khatau Tank Pakhadi Road, Byculla (W), PG 3444 Chawl Mumbai 400 011 16 Plot in between Sarovar, B.J.Marg, Byculla (W), Mumbai RG 230 Chaitanya, Parijat buildings 400 011 (MHADA) 17 Mominpura Patra Chawl Tank Pakhadi Road, Byculla (W), RG 3352 Mumbai 400 011. 18 Hanuman Prasad Building Bapurao Jagtap Road, Byculla PG 9610 Page 1 of 4 Reservation Area As Per Sr. -

Bandra Book Aw.Qxp

ON THE WATERFRONT Reclaiming Mumbai’s Open Spaces P.K. Das & Indra Munshi This is dummy text pls do not read please do not read this text. This is Dummy text please do not read this text. this is dummy text This is dummy text pls do not read please do not read this text. This is Dummy text please do not read this text. this is dummy text ISBN: 12345678 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in retrieved system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. 2 Contents 5 Preface 7 Declining open spaces in Mumbai Lack of planning for the city Encroachments New open spaces 29 Abuse of Mumbai’s waterfront How accessible is the waterfront? Is the waterfront protected? Landfill and its consequences State of the mangroves Coastal pollution 65 Bandra’s activism: Evolving an agenda The making of Bandra Its seafront Struggles to protect the seafront 89 Reclaiming the waterfront Planning for the promenades Popularising the waterfront Issues arising from Bandra’s experience 137 Democratising public spaces Conclusion 151 Appendix 159 Maps 3 4 Preface What began as a story of Bandra’s activism to reclaim and democratise its waterfront grew into a study of Mumbai’s dwindling public spaces, especially the seafront. This book draws from our expertise in sociology, architecture and urban planning and, above all, our commitment to millions of people who suffer as a result of the degradation of our urban environment and for whom Mumbai means noise, pollution and congestion.