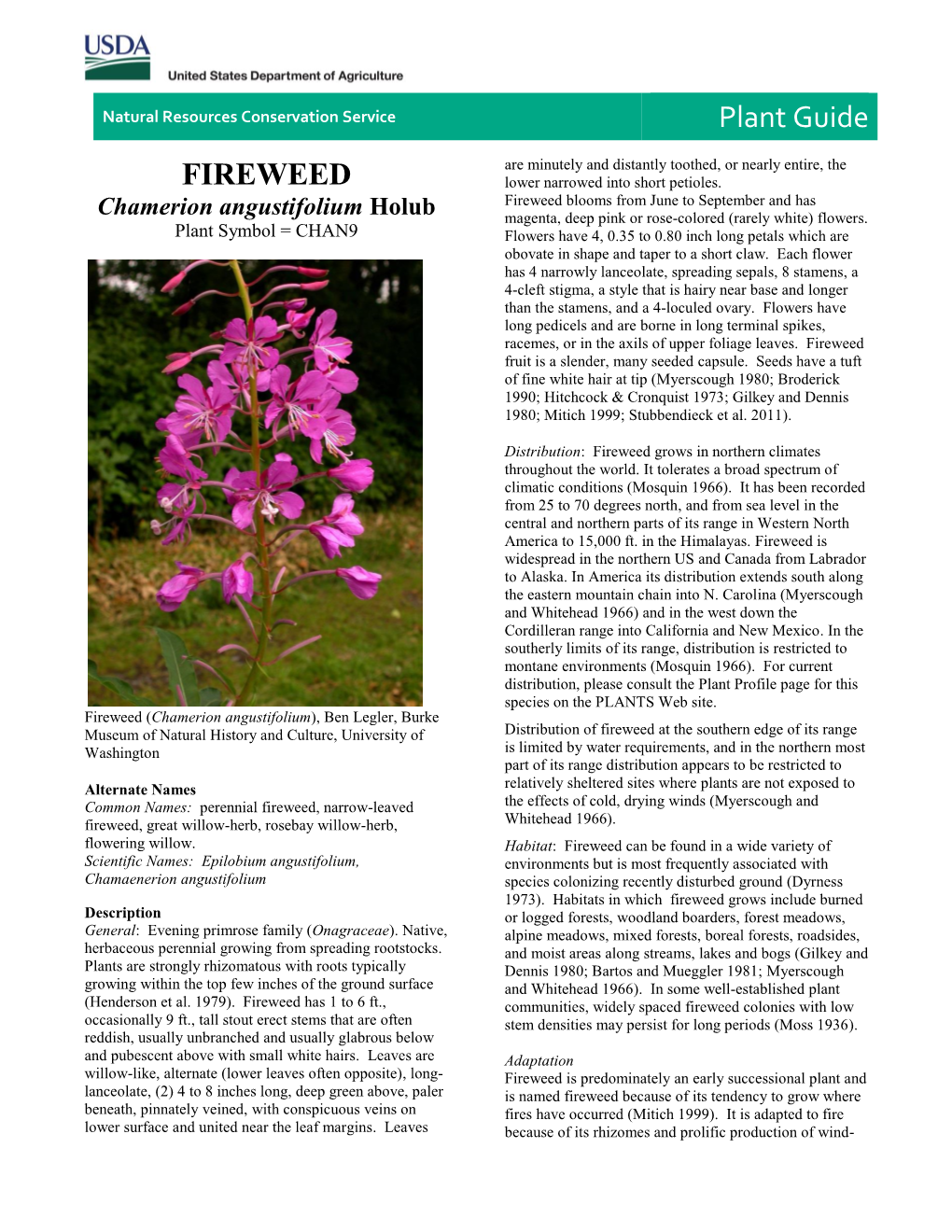

Fireweed (Chamerion Angustifolium) Plant Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WRITTEN FINDINGS of the WASHINGTON STATE NOXIOUS WEED CONTROL BOARD 2018 Noxious Weed List Proposal

DRAFT: WRITTEN FINDINGS OF THE WASHINGTON STATE NOXIOUS WEED CONTROL BOARD 2018 Noxious Weed List Proposal Scientific Name: Tussilago farfara L. Synonyms: Cineraria farfara Bernh., Farfara radiata Gilib., Tussilago alpestris Hegetschw., Tussilago umbertina Borbás Common Name: European coltsfoot, coltsfoot, bullsfoot, coughwort, butterbur, horsehoof, foalswort, fieldhove, English tobacco, hallfoot Family: Asteraceae Legal Status: Proposed as a Class B noxious weed for 2018, to be designated for control throughout Washington, except for in Grant, Lincoln, Adams, Benton, and Franklin counties. Images: left, blooming flowerheads of Tussilago farfara, image by Caleb Slemmons, National Ecological Observatory Network, Bugwood.org; center, leaves of T. farfara growing with ferns, grasses and other groundcover species; right, mature seedheads of T. farfara before seeds have been dispersed, center and right images by Leslie J. Mehrhoff, University of Connecticut, Bugwood.org. Description and Variation: The common name of Tussilago farfara, coltsfoot, refers to the outline of the basal leaf being that of a colt’s footprint. Overall habit: Tussilago farfara is a rhizomatous perennial, growing up to 19.7 inches (50 cm tall), which can form extensive colonies. Plants first send up flowering stems in the spring, each with a single yellow flowerhead. Just before or after flowers have formed seeds, basal leaves on long petioles grow from the rhizomes, with somewhat roundish leaf blades that are more or less white-woolly on the undersides. Roots: Plants have long creeping, white scaly rhizomes (Griffiths 1994, Chen and Nordenstam 2011). Rhizomes are branching and have fibrous roots (Barkley 2006). They are also brittle and can break easily (Pfeiffer et al. -

Notes on Epilobium (Onagraceae) from the Western Mediterranean

NOTES ON EPILOBIUM (ONAGRACEAE) FROM THE WESTERN MEDITERRANEAN by GONZALO NETO FELINER* Resumen NIETO FELINER, G. (1996). Notas sobre los Epilobium (Onagraceae) del Mediterráneo occidental. Anales Jard. Bot. Madrid 54: 255-264 (en inglés). Aportaciones taxonómicas sobre el género Epilobium que son consecuencia de la revisión lle- vada a cabo para producir una síntesis genérica destinada a Flora iberica. En particular, se acla- ran nombres tales como E. mutabile Boiss. & Reut., E. carpetanum Willk., E. psilotum Maire & Samuelsson o E. salcedoi Vicioso, así como varios creados por Sennen (E. barcinonense, E. gredillae, E. losae, E. rigatum, E. barnadesianum, E. debile, E. costeanum) y por Merino (£. maciae, E. simulans, E. tudense y E. lucense). Asimismo, se discute en detalle el problema de E. lamyi F.W. Schultz; en especial, se aclara el uso de dicho nombre por parte de botánicos que han trabajado en España y Portugal, y se rechazan las citas peninsulares del mismo. Se explican algunos problemas taxonómicos derivados de la variabilidad morfológica que exhiben E. duriaei, E. montanum, E. lanceolatum, E. collinum, E. tetragonum subsp. tournefortii y E. obscurum. De este último, adicionalmente, se aportan algunos datos de interés corológico. Palabras clave: Spermatophyta, Epilobium, Onagraceae, taxonomía, corología, Mediterráneo occidental. Abstract NIETO FELINER, G. (1996). Notes on Epilobium (Onagraceae) from the western Mediterranean. Anales Jard. Bot. Madrid 54: 255-264. The present taxonomic notes are part of the results of a revisión of Epilobium carried out for the "Flora iberica" project. The identity of diverse ñames is clarified, including E. mutabile Boiss. & Reut., E. carpetanum Willk., E. psilotum Maire & Samuelsson, E. -

Habitat Indicator Species

1 Handout 6 – Habitat Indicator Species Habitat Indicator Species The species lists below are laid out by habitats and help you to find out which habitats you are surveying – you will see that some species occur in several different habitats. Key: * Plants that are especially good indicators of that specific habitat Plants found in Norfolk’s woodland Common Name Scientific Name Alder Buckthorn Frangula alnus Aspen Populus tremula Barren Strawberry Potentilla sterilis Bird Cherry Prunus padus Black Bryony Tamus communis Bush Vetch Vicia sepium Climbing Corydalis Ceratocapnos claviculata Common Cow-wheat Melampyrum pratense Early dog violet Viola reichenbachiana Early Purple Orchid Orchis mascula * English bluebell Hyacinthoides non-scripta* * Field Maple Acer campestre* Giant Fescue Festuca gigantea * Goldilocks buttercup Ranunculus auricomus* Great Wood-rush Luzula sylvatica Greater Burnet-saxifrage Pimpinella major Greater Butterfly-orchid Platanthera chlorantha Guelder Rose Viburnum opulus Hairy Wood-rush Luzula pilosa Hairy-brome Bromopsis ramosa Hard Fern Blechnum spicant Hard Shield-fern Polystichum aculeatum * Hart's-tongue Phyllitis scolopendrium* Holly Ilex aquifolium * Hornbeam Carpinus betulus* * Midland Hawthorn Crataegus laevigata* Moschatel Adoxa moschatellina Narrow Buckler-fern Dryopteris carthusiana Opposite-leaved Golden-saxifrage Chrysosplenium oppositifolium * Pendulous Sedge Carex Pendula* Pignut Conopodium majus Polypody (all species) Polypodium vulgare (sensulato) * Primrose Primula vulgaris* 2 Handout 6 – Habitat -

Appendix C. Plant Species Observed at the Yolo Grasslands Regional Park (2009-2010)

Appendix C. Plant Species Observed at the Yolo Grasslands Regional Park (2009-2010) Plant Species Observed at the Yolo Grassland Regional Park (2009-2010) Wetland Growth Indicator Scientific Name Common Name Habitat Occurrence Habit Status Family Achyrachaena mollis Blow wives AG, VP, VS AH FAC* Asteraceae Aegilops cylinricia* Jointed goatgrass AG AG NL Poaceae Aegilops triuncialis* Barbed goat grass AG AG NL Poaceae Aesculus californica California buckeye D T NL Hippocastanaceae Aira caryophyllea * [Aspris c.] Silver hairgrass AG AG NL Poaceae Alchemilla arvensis Lady's mantle AG AH NL Rosaceae Alopecurus saccatus Pacific foxtail VP, SW AG OBL Poaceae Amaranthus albus * Pigweed amaranth AG, D AH FACU Amaranthaceae Amsinckia menziesii var. intermedia [A. i.] Rancher's fire AG AH NL Boraginaceae Amsinckia menziesii var. menziesii Common fiddleneck AG AH NL Boraginaceae Amsinckia sp. Fiddleneck AG, D AH NL Boraginaceae Anagallis arvensis * Scarlet pimpernel SW, D, SS AH FAC Primulaceae Anthemis cotula * Mayweed AG AH FACU Asteraceae Anthoxanthum odoratum ssp. odoratum * Sweet vernal grass AG PG FACU Poaceae Aphanes occidentalis [Alchemilla occidentalis] Dew-cup AG, F AH NL Rosaceae Asclepias fascicularis Narrow-leaved milkweed AG PH FAC Ascepiadaceae Atriplex sp. Saltbush VP, SW AH ? Chenopodiaceae Avena barbata * Slender wild oat AG AG NL Poaceae Avena fatua * [A. f. var. glabrata, A. f. var. vilis] Wild oat AG AG NL Poaceae Brassica nigra * Black mustard AG, D AH NL Brassicaceae Brassica rapa field mustard AG, D AH NL Brassicaceae Briza minor * Little quakinggrass AG, SW, SS, VP AG FACW Poaceae Brodiaea californica California brodiaea AG PH NL Amaryllidaceae Brodiaea coronaria ssp. coronaria [B. -

Northern Willowherb Control in Nursery Containers James Altland

Northern Willowherb Control in Nursery Containers James Altland North Willamette Research and Extension Center Oregon State University Aurora, OR 97002 [email protected] Introduction Northern willowherb (Epilobium ciliatum Rafin, syn. E. adenocaulon Hauss.) is a perennial in the family Onagraceae and is native to North America. Northern willowherb is one of the most prevalent weed species in west coast container nurseries and is becoming increasingly problematic in cooler regions along the east coast. E. ciliatum is wrongly, but commonly, referred to as fireweed by many west coast nurserymen. Northern willowherb is also known by the common names hairy willowherb, slender willowherb, or fringed willowherb depending on the region where it is found. A single plant can produce up to 60,000 seeds per plant per season. Seeds are attached to a tuft of hair which aid in wind dispersal allowing for widespread seed dissemination in container nurseries. Northern willowherb germinates in dry to water logged soils, and is particularly well suited for establishing in dry soils compared to other species in the same genera. Northern willowherb seeds germinate readily in full sun (100%) or darkness (84%), making them well adapted to germination in containers with little or complete cover from crop canopies. Seeds can germinate over a range of temperatures from 4 to 36C, although germination is reduced as temperatures approach 30C. This allows for germination to occur throughout the spring and summer growing season in northern climates, and virtually year-round in protected container crops. It also explains why its spread has been primarily limited to cooler summer climates typical of the west coast and northeast U.S. -

Vestured Pits in Wood of Onagraceae: Correlations with Ecology, Habit, and Phylogeny1

VESTURED PITS IN WOOD OF Sherwin Carlquist2 and Peter H. Raven3 ONAGRACEAE: CORRELATIONS WITH ECOLOGY, HABIT, AND PHYLOGENY1 ABSTRACT All Onagraceae for which data are available have vestured pits on vessel-to-vessel pit pairs. Vestures may also be present in some species on the vessel side of vessel-to-ray pit pairs. Herbaceous Onagraceae do not have fewer vestures, although woods with lower density (Circaea L. and Oenothera L.) have fewer vestures. Some Onagraceae from drier areas tend to have smaller vessel pits, and on that account may have fewer vestures (Epilobium L. and Megacorax S. Gonz´alez & W. L. Wagner). Pit apertures as seen on the lumen side of vessel walls are elliptical, occasionally oval, throughout the family. Vestures are predominantly attached to pit aperture margins. As seen from the outer surfaces of vessels, vestures may extend across the pit cavities. Vestures are usually absent or smaller on the distal portions of pit borders (except for Ludwigia L., which grows consistently in wet areas). Distinctive vesture patterns were observed in the several species of Lopezia Cav. and in Xylonagra Donn. Sm. & Rose. Vestures spread onto the lumen-facing vessel walls of Ludwigia octovalvis (Jacq.) P. H. Raven. Although the genera are presented here in the sequence of a recent molecular phylogeny of Onagraceae, ecology and growth forms are more important than evolutionary relationships with respect to abundance, degree of grouping, and morphology of vestured pits. Designation of vesture types is not warranted based on the distribution of named types in Onagraceae and descriptive adjectives seem more useful, although more data on vesturing in the family are needed before patterns of diversity and their extent can be fully ascertained. -

MONITORING REPORT 2020 BILL BUDD It Is with Great Sadness That We Must Report the Death of Bull Budd in Autumn 2020

Wimbledon and Putney Commons ECOLOGICAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL MONITORING REPORT 2020 BILL BUDD It is with great sadness that we must report the death of Bull Budd in autumn 2020. Bill was our much respected, dragonfly and damselfly recorder and a member of the Wildlife and Conservation Forum. As well as recording on the Commons, Bill also worked as a volunteer at the London Natural History Museum for many years and was the Surrey Vice County Dragonfly Recorder. Bill supported our BioBlitz activities and, with others from the Forum, led dedicated walks raising public awareness of the dragonfly and damselfly populations on the Commons. In September 2020 in recognition of his outstanding contributions to the recording and conservation of Odonata, a newly identified dragonfly species found in the Bornean rainforest* was named Megalogomphus buddi. His contributions will be very much missed. * For further information see: https://british-dragonflies.org.uk/dragonfly-named-after-bds-county-dragonfly-recorder-bill-budd/ Dow, R.A. and Price, B.W. (2020) A review of Megalogomphus sumatranus (Krüger, 1899) and its allies in Sundaland with a description of a new species from Borneo (Odonata: Anisoptera: Gomphidae). Zootaxa 4845 (4): 487–508. https://www.mapress.com/j/zt/article/view/zootaxa.4845.4.2 Accessed 24.02.2021 Thanks are due to everyone who has contributed records and photographs for this report; to the willing volunteers; for the support of Wildlife and Conservation Forum members; and for the reciprocal enthusiasm of Wimbledon and Putney Commons’ staff. A special thank you goes to Angela Evans-Hill for her help with proof reading, chasing missing data and assistance with the final formatting, compilation and printing of this report. -

Epilobium Hirsutum L. (Onagraceae): a New Distributional Report for Northern Haryana, India

Journal on New Biological Reports ISSN 2319 – 1104 (Online) JNBR 5(3) 178 – 179 (2016) Published by www.researchtrend.net Epilobium hirsutum L. (Onagraceae): A New Distributional Report for Northern Haryana, India Inam Mohammed & Amarjit Singh* Guru Nanak Khalsa College, Yamuna Nagar,Haryana,India. *Corresponding author: [email protected] | Received: 24 November2016 | Accepted: 26 December 2016 | ABSTRACT The paper presents a taxon namely Epilobium hirsutum L. a showy member of Onagraceae and a Eurasian species collected and identified for the first time from district Yamuna nagar, Nothern Haryana. Key Words: Epilobium, Eurasian, Northern Haryana. INTRODUCTION The genus Epilobium L. with more than 300 specimens from Meerut region near Ganga canal. species occurs in all continents relatively at high Malik et al (2014) collected and identified this altitudes. Clarke (1879) described 12 species under species from district Saharanpur of Uttar Pradesh. the genus Epilobium from East and North- East During the survey of district Yamuna Nagar of Himalaya. Raven (1962) recognized 37 species, Haryana, authors reported three sites of this which include 13 new taxa from the Himalayan species, covering an estimated 325 km square area. region and recorded 31 taxa from India. In the 20th Collected specimens were critically examined with century Peter H. Raven (1976) has researched relevant literature and identified with the help of phylogeny and systematics of willow herbs DD herbarium and BSD herbarium Dehradun. extensively. Giri and Banerjee (1984) wrote Identified specimens have been deposited in identification and distributional note on a few herbarium of Guru Nanak Khalsa College, Yamuna species of Epilobium. In Western Himalayas E. -

Diversification in the Microlepidopteran Genus Mompha (Lepidoptera: Gelechioidea

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/466052; this version posted November 8, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 1 Diversification in the microlepidopteran genus Mompha (Lepidoptera: Gelechioidea: 2 Momphidae) is explained more by tissue specificity than host plant family. 3 4 5 Authors: Daniel J. Bruzzese1,2,#b,*, David L. Wagner3, Terry Harrison4, Tania Jogesh2, Rick P. 6 Overson2, 5, Norman J. Wickett1,2, Robert A. Raguso6, and Krissa A. Skogen1,2 7 8 9 10 1 Department of Plant Biology and Conservation, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA. 11 2 Division of Plant Science and Conservation, Chicago Botanic Garden, Glencoe, IL, USA. 12 3 Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, USA. 13 4 345 N. 7th St., Charleston, IL USA. 14 5 Global Institute of Sustainability, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA. 15 6 Department of Neurobiology and Behavior, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA. 16 #b Current Address: Department of Biological Sciences, University of Notre Dame, South Bend, 17 IN, USA. 18 19 20 *Corresponding author 21 E-mail: [email protected] (DJB) 22 23 24 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/466052; this version posted November 8, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

Plant Species to AVOID for Landscaping, Revegetation, and Restoration Colorado Native Plant Society Revised by the Horticulture and Restoration Committee, May, 2002

Plant Species to AVOID for Landscaping, Revegetation, and Restoration Colorado Native Plant Society Revised by the Horticulture and Restoration Committee, May, 2002 The plants listed below are invasive exotic species which threaten or potentially threaten natural areas, agricultural lands, and gardens. This is a working list of species which have escaped from landscaping, reclamation projects, and agricultural activity. All problem plants may not be included; contact the Colorado Dept. of Agriculture for more information (see references below). Some drought resistent, well adapted exotic plants suggested for landscaping survive successfully outside cultivation. If you are unsure about introducing a new plant into your garden or reclamation/restoration plans, maintain a conservative approach. Try to research a new plant thoroughly before using it, or omit it from your plans. While there are thousands of introduced plants which pose no threats, there are some that become invasive, displacing and outcompeting native vegetation, and cost land managers time and money to deal with. If you introduce a plant and notice it becoming aggressive and invasive, remove it and report your experience to us, your county extension agent, and the grower. If you see a plant for sale that is listed on the Colorado Noxious Weed List, please report it to the CO Dept. of Ag. (Jerry Cochran, Nursery Specialist; 303.239.4153). This list will be updated periodically as new information is received. For more information, including a list of suggested native plants for horticultural use, and to contact us, please visit our website at www.conps.org. NOX NE & NRCS INV RMNP WISC CA CoNPS CD PCA UM COMMENTS COMMON NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME* (CO) GP INVASIVE EXOTIC FORBS – Often found in seed mixes or nurseries Baby's breath Gypsophila paniculata X X X X NATIVE ALTERNATIVES: Native penstemon Saponaria officinalis (Lychnis (Penstemon spp.); Rocky Mtn Beeplant (Cleome Bouncing bet, soapwort X X X X X saponaria) serrulata); Native white yarrow (Achillea lanulosa). -

Skokholm Annual Report 2017

Wardens’ Report iii Introduction to the Skokholm Island Annual Report 2017 iii The 2017 Season and Weather Summary v Spring Work Parties vii Spring Long-term Volunteers viii Spring Migration Highlights viii The Breeding Season x Autumn Migration Highlights xi Autumn Long-term Volunteers xii Autumn Work Party xii Skokholm Bird Observatory xiii Digitisation of the Paper Logs xiii Ringing Projects xiii Visiting Ringers xiv Birds Ringed in 2017 xv Catching Methods xv Arrival and Departure Dates xvii 2016 Rarity Decisions and DNA Results xvii Bird Observatory Fundraising xviii Acknowledgments and Thanks xviii Definitions and Terminology 1 The Systematic List of Birds 1 Anatidae Geese and Ducks 1 Phasianidae Quail 7 Gaviidae Divers 7 Hydrobatidae Storm Petrel 7 Procellariidae Fulmar and Shearwaters 17 Podicipedidae Grebes 31 Threskiornithidae Spoonbill 31 Ardeidae Bittern, Grey Heron and Egrets 32 Sulidae Gannet 33 Phalacrocoracidae Shag and Cormorant 34 Accipitridae Hawks, Hen Harrier, Red Kite & Buzzard 36 Rallidae Water Rail, Moorhen and Coot 39 Gruidae Crane 41 Haematopodidae Oystercatcher 42 Recurvirostridae Avocet 43 Charadriidae Plovers 44 Scolopacidae Sandpipers and allies 45 Laridae Gulls 57 Sternidae Terns 75 Stercorariidae Skuas 76 Alcidae Auks 77 Columbidae Pigeons and Doves 94 Cuculidae Cuckoo 95 Strigidae Short-eared Owl 96 Apodidae Swift 97 Upupidae Hoopoe 97 Picidae Wryneck 98 Falconidae Kestrel, Merlin and Peregrine 98 Corvidae Crows 100 ii | Skokholm Annual Report 2017 Paridae Blue Tit 106 Alaudidae Skylark 107 Hirundinidae -

Plants and Plant Parts

BVL-Report · 8.8 List of Substances of the Competent Federal Government and Federal State Authorities Category “Plants and plant parts” List of Substances of the Competent Federal Government and Federal State Authorities Category “Plants and plant parts” List of Substances of the Competent Federal Government and Federal State Authorities Category “Plants and plant parts” BVL-Reporte IMPRINT ISBN 978-3-319-10731-8 ISBN 978-3-319-10732-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-10732-5 Springer Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broad- casting, reproduction on microfilm or in any other way, and storage in data banks. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the German Copyright Law of September 9, 1965, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. Violations are liable to prosecution under the German Copyright Law. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. While the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication, neither the authors nor the editors nor the publisher can accept any legal responsibility for any errors or omissions that may be made.