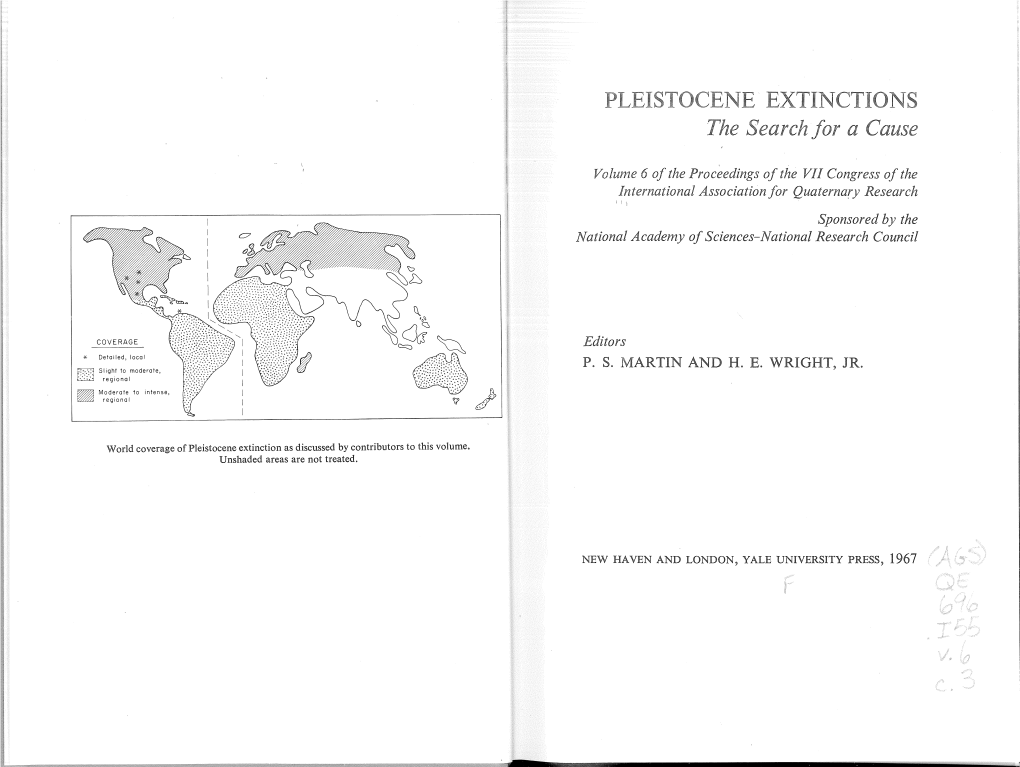

EXTINCTIONS the Search for a Cause

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fresh- and Brackish-Water Cold-Tolerant Species of Southern Europe: Migrants from the Paratethys That Colonized the Arctic

water Review Fresh- and Brackish-Water Cold-Tolerant Species of Southern Europe: Migrants from the Paratethys That Colonized the Arctic Valentina S. Artamonova 1, Ivan N. Bolotov 2,3,4, Maxim V. Vinarski 4 and Alexander A. Makhrov 1,4,* 1 A. N. Severtzov Institute of Ecology and Evolution, Russian Academy of Sciences, 119071 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] 2 Laboratory of Molecular Ecology and Phylogenetics, Northern Arctic Federal University, 163002 Arkhangelsk, Russia; [email protected] 3 Federal Center for Integrated Arctic Research, Russian Academy of Sciences, 163000 Arkhangelsk, Russia 4 Laboratory of Macroecology & Biogeography of Invertebrates, Saint Petersburg State University, 199034 Saint Petersburg, Russia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Analysis of zoogeographic, paleogeographic, and molecular data has shown that the ancestors of many fresh- and brackish-water cold-tolerant hydrobionts of the Mediterranean region and the Danube River basin likely originated in East Asia or Central Asia. The fish genera Gasterosteus, Hucho, Oxynoemacheilus, Salmo, and Schizothorax are examples of these groups among vertebrates, and the genera Magnibursatus (Trematoda), Margaritifera, Potomida, Microcondylaea, Leguminaia, Unio (Mollusca), and Phagocata (Planaria), among invertebrates. There is reason to believe that their ancestors spread to Europe through the Paratethys (or the proto-Paratethys basin that preceded it), where intense speciation took place and new genera of aquatic organisms arose. Some of the forms that originated in the Paratethys colonized the Mediterranean, and overwhelming data indicate that Citation: Artamonova, V.S.; Bolotov, representatives of the genera Salmo, Caspiomyzon, and Ecrobia migrated during the Miocene from I.N.; Vinarski, M.V.; Makhrov, A.A. -

Roacht1 Extquoteright S Mouse-Tailed Dormouse Myomimus

Published by Associazione Teriologica Italiana Volume 23 (2): 67–71, 2012 Hystrix, the Italian Journal of Mammalogy Available online at: http://www.italian-journal-of-mammalogy.it/article/view/4779/pdf doi:10.4404/hystrix-23.2-4779 Research Article Roach’s mouse-tailed dormouse Myomimus roachi distribution and conservation in Bulgaria Boyan Milcheva,∗, Valeri Georgievb aUniversity of Forestry; Wildlife Management Department, 10 Kl. Ochridski Blvd., BG-1765 Sofia, Bulgaria bMinistry of Environment and Water, 22 Maria Luisa Blvd., BG-1000 Sofia, Bulgaria Keywords: Abstract Roach’s mouse-tailed dormouse Myomimus roachi The Roach’s mouse-tailed dormice (Myomimus roachi) is an endangered distribution mammal in Europe with poorly known distribution and biology in Bulgaria. conservation Cranial remains of 15 specimens were determined among 30532 mammals Bulgaria in Barn Owl (Tyto alba) pellets in 35 localities from 2000 to 2008 and 32941 mammals in Eagle Owl (Bubo bubo) pellets in 59 localities from 1988 to 2011 in SE Bulgaria. This dormouse was present with single specimens in 11 localities and whit 4 specimens in one locality. It is one of the rarest Article history: mammals in the region that forms only up to 1% by number of mammalian Received: 19 January 2012 prey in the more numerous pellet samples. The existing protected areas Accepted: 3 April 2012 ecological network covers six out of 15 (40%) localities where the species has been detected in the last two decades. We discuss the necessity of designation of new Natura 2000 zones for the protection of the Roach’s mouse-tailed dormouse in Bulgaria. -

THE American Museum Journal

T ///^7; >jVvvscu/n o/ 1869 THE LIBRARY THE American Museum Journal VOLUME VII, 1907 NEW YORK: PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY 1907 Committee of Publication EDMUND OTIS HOVF.Y, Ediior. FRANK M. ( IIAPMAN ] LOUIS P. GHATACAP \ .l<lris-on/ linanl WILLIAM K. GREGOIlvJ THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY. 77th Street and Central Park West, New York. OFFICERS AND COMMITTEES PRESIDEXT MORRIS K. JESUP FIRST VICE-PRESIDENT SECOND VICE-PRESIDENT J. PIERPONT MORGAN HENRY F. OSBORN TREASURER SECRETARY CHARLES LANIER J. HAMPDEN ROBB ASSISTANT SECRETARY AND DIRECTOR ASSISTANT TREASURER HERMON C. BUMPUS GEORGE H. SHERWOOD BOARD OF TRUSTEES Class of 1907 D. O. :\IILLS ALBERT S. BICKMORE ARCHIBALD ROGERS CORNELIUS C. CUYLER ADRIAN ISELIN, Jr. Class of 1908 H. o. have:\ieyer Frederick e. hyde A. I). JUHJJAIU) GEORCiE S. BOWDOIN (TEVELANl) H. DOIXJE Class of 1909 MORRIS K. JESUP J. PIERPONT MORGAN JOSEPH H. CHOATE GEORGE G. HAVEN HENRY F. OSBORN Class of 1910 J. HAMPDEN ROBB PERCY R. PYNE ARTHUR CURTISS JAMES Class of 1911 CHARLES LANIER WILLIAISI ROCKEFELLER ANSON W. HARD GUSTAV E. KISSEL SETH LOW Scientific Staff DIRECTOR Hermon C. Bumpus, Ph.D., Sc. D. DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION Prof. Albert S. Bickmore, B. S., Ph.D., LL.D., Curator Emeritus George H. Shehwood, A.B., A.M., Curator DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND INVERTEBRATE PALEONTOLOGY Prof. R. P. Whitfield, A.M., Curator Edmund Otis Hovey, A.B., Ph.D., Associate Curator DEPARTMENT OF MAMMALOGY AND ORNITHOLOGY Prof. J. A. Allen, Ph.D., Curator Frank M. Chapman, Associate Curator DEPARTMENT OF VERTEBRATE PALAEONTOLOGY Prof. -

Population Genetic Analysis of the Estonian Native Horse Suggests Diverse and Distinct Genetics, Ancient Origin and Contribution from Unique Patrilines

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article Population Genetic Analysis of the Estonian Native Horse Suggests Diverse and Distinct Genetics, Ancient Origin and Contribution from Unique Patrilines Caitlin Castaneda 1 , Rytis Juras 1, Anas Khanshour 2, Ingrid Randlaht 3, Barbara Wallner 4, Doris Rigler 4, Gabriella Lindgren 5,6 , Terje Raudsepp 1,* and E. Gus Cothran 1,* 1 College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA 2 Sarah M. and Charles E. Seay Center for Musculoskeletal Research, Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for Children, Dallas, TX 75219, USA 3 Estonian Native Horse Conservation Society, 93814 Kuressaare, Saaremaa, Estonia 4 Institute of Animal Breeding and Genetics, University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna, 1210 Vienna, Austria 5 Department of Animal Breeding and Genetics, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, 75007 Uppsala, Sweden 6 Livestock Genetics, Department of Biosystems, KU Leuven, B-3001 Leuven, Belgium * Correspondence: [email protected] (T.R.); [email protected] (E.G.C.) Received: 9 August 2019; Accepted: 13 August 2019; Published: 20 August 2019 Abstract: The Estonian Native Horse (ENH) is a medium-size pony found mainly in the western islands of Estonia and is well-adapted to the harsh northern climate and poor pastures. The ancestry of the ENH is debated, including alleged claims about direct descendance from the extinct Tarpan. Here we conducted a detailed analysis of the genetic makeup and relationships of the ENH based on the genotypes of 15 autosomal short tandem repeats (STRs), 18 Y chromosomal single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), mitochondrial D-loop sequence and lateral gait allele in DMRT3. -

Rewilding: Definitions, Success Factors and Policy, a European Perspective

Rewilding: definitions, success factors and policy, a European perspective Ashleigh Campbell Supervisors: 12910708 Kenneth Rijsdijk Date submitted: 01/12/20 and Carina Hoorn 1 2 Contents Abstract............................................................................................................................................................................. 4 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................. 5 2. Oostvaardersplassen, the Netherlands: Grazer-managed grasslands in a man-made nature reserve ................. 6 3. What is rewilding? .................................................................................................................................................... 8 4. Why rewild? ............................................................................................................................................................ 10 5. Policy and socio-economic implications ................................................................................................................ 11 6. Ecological success factors and progress in rewilding ............................................................................................ 13 7. Trophic rewilding and the landscape of fear ......................................................................................................... 16 8. What factors are essential for success in a rewilding project? ............................................................................ -

TARPAN Or KONIK.Rtf

TARPAN OR KONIK ? An analysis of “semantic denaturation” The horse which is in the process of becoming de-domesticated and recovering little by little its place in some European ecosystems, especially in the Netherlands, often comes under the name of the Konik (or Konik Polski).This name, imported from Poland, is used inasmuch as the name Tarpan is considered to be applicable to the wild horse which reputedly ceased to exist in 1879. This deliberately limiting choice fails to take into account a certain number of scientific and historical facts. Moreover, it maintains an erroneous perception of the horse with the public which in general finds it hard to imagine that a horse can leave the domestic arena. The descendant of the wild horse which became the little Polish horse After the discovery of descendants of the tarpan with farmers of the Bilgoraj region at the beginning of the 20th century, Professor Tadeusz Vetulani undertook to save this primitive strain. His aim was to get back to the wild tarpan and introduce it, like the European bison, into its last-known refuge: the Bialowieza Forest. When Vetulani died in 1952, the dominant influence of some horse specialists ended up by consigning this horse to the traditional horse world, by giving it the official name of Konik Polski, literally "little Polish horse". Hence a genuine universal zoological heritage was relegated to the rank of a mere national breed of horse. Incidentally, it should be mentioned that if this horse is not specifically Polish (as is the case of the European bison), it is not "little" either. -

Rewilding and Ecosystem Services

¢ POSTNOTE Number 537 September 2016 Rewilding and Ecosystem Services Overview ¢ Rewilding aims to restore natural processes that are self-regulating, reducing the need for human management of land. ¢ Few rewilding projects are underway, and there is limited evidence on their impacts. ¢ Rewilding may provide ecosystem services such as flood prevention, carbon storage and recreation. It often has low input costs, but can still benefit biodiversity. ¢ Some valued and protected priority habitats such as chalk grassland currently depend on agricultural practices like grazing. This POSTnote explores the consequences of Rewilding may not result in such habitats. increasing the role of natural processes within ¢ No government policy refers explicitly to landscapes. Evidence from the UK and abroad rewilding, but it has the potential to suggests that rewilding can benefit both wildlife complement existing approaches to meet and local people, but animal reintroductions commitments on habitat restoration. could adversely affect some land-users. What is Rewilding? Rewilding and Current Conservation Practice There is no single definition of rewilding, but it generally UK landscapes have been managed to produce food and refers to reinstating natural processes that would have wood for millennia, and 70% of land is currently farmed.9 occurred in the absence of human activity.1,2 These include €3bn per year is spent on environmental management of vegetation succession, where grasslands develop into farmland across the EU.10,11 This includes maintaining wetlands or forests, and ecological disturbances caused by wildlife habitats on farmland such as heathland and chalk disease, flooding, fire and wild herbivores (plant eaters). grassland, which involves traditional agricultural practices Initially, natural processes may be restored through human such as fire and grazing.12,13 Rewilding involves ecological interventions such as tree planting, drainage blocking and restoration (the repair of degraded ecosystems),14 and reintroducing “keystone species”3,4 like beavers. -

Evolution of Corvids and Their Presence in the Neogene and the Quaternary in the Carpathian Basin

Ornis Hungarica 2020. 28(1): 121–168. DOI: 10.2478/orhu-2020-0009 Evolution of Corvids and their Presence in the Neogene and the Quaternary in the Carpathian Basin Jenő (Eugen) KESSLER Received: September 09, 2019 – Revised: February 12, 2020 – Accepted: February 18, 2020 Kessler, J. (E.) 2020. Evolution of Corvids and their Presence in the Neogene and the Quater- nary in the Carpathian Basin. – Ornis Hungarica 28(1): 121–168. DOI: 10.2478/orhu-2020-0009 Abstract: Corvids are the largest songbirds in Europe. They are known in the avian fauna of Europe from the Miocene, the beginning of the Neogene, and are currently represented by 11 species. Due to their size, they occur more frequently among fossilized material than other types of songbirds, and thus have been examined to the largest extent. In the current article, we present their known evolution and their fossilized taxa in Europe and examine the osteology of extant species. Keywords: Corvidae, Neogene, Quaternary, Europe, Carpathian Basin, osteology Összefoglalás: A varjúfélék a legnagyobb termetű, Európában is elterjedt énekesmadarak. A kontinens madárfau- nájában a neogén elejétől, a miocénból ismertek, és jelenleg 11 fajjal vannak képviselve. Termetük következtében gyakrabban előfordulnak a fosszilis anyagban, mint a többi énekesmadár típus, és ennek következtében nagyobb mértékben is tanulmányozták őket. Jelen tanulmányban bemutatjuk az ismert európai evolúciójukat és fosszilis taxonjaikat, és foglalkozunk a recens fajok csonttanával is. Kulcsszavak: Corvidae, neogén, negyedidőszak, Európa, Kárpát-medence, csonttan Department of Paleontology, Eötvös Loránd University, 1117 Budapest, Pázmány Péter sétány 1/c, Hungary, e-mail: [email protected] Introduction About half of the current avian species – if not more – consists of songbirds, which are dis- tributed all around the world apart from Antarctica with a large number of specimens. -

Busby, D. & Rutland, C. (2019). the Horse. a Natural History. Brighton

Review of: Busby, D. & Rutland, C. (2019). The ed. The origins of the modern domestic horse are Horse. A Natural History. Brighton: Ivy Press. explored in depth, portraying the tarpan as its an- 224 pages, 225 figures (partly colour), hard cover. cestor and Przewalskis as the sole wild horse spe- ISBN 978-1-78240-565-8. cies still in existence. However, this is now outdat- ed knowledge as has been shown by new research, Helene Benkert published in the last two years. GAUNITZ ET AL (2018) and FAGES ET AL (2019) examined and reviewed This richly illustrated book is a well-presented DNA samples of horses from a variety of periods compendium of the horse, its biology, evolution and regions in order to investigate the genetic ori- and its history with humanity. Clearly structured gin of the modern horse. Their research clearly and organised, it is a compelling account of an shows that Przewalski horses are not the last living exceptional species. Throughout, the authors’ re- species of wild horses previously thought, but in gard and respect for horses is apparent but does fact descendants of some of the earliest domesti- not hinder the scientific narrative. On the contra- cated horses. The Eneolithic site of Botai in modern ry, the positive approach to communication, in Kazakhstan yielded some of the earliest evidence combination with plenty of high-quality photo- of horse husbandry and domestication (OUTRAM graphs and schematics, supports the reader’s in- ET AL., 2009). Genetic analysis of the Botai horses terest and inspires to learn more. shows that they are direct ancestors of Przewalski It is largely written in a straightforward and horses but a minimal component in modern do- adequately flowing language, with a clear sen- mestic horses. -

LIFE and European Mammals Mammals European and LIFE

NATURE LIFE and European Mammals Improving their conservation status LIFE Focus I LIFE and European Mammals: Improving their conservation status EUROPEAN COMMISSION ENVIRONMENT DIRecTORATE-GENERAL LIFE (“The Financial Instrument for the Environment”) is a programme launched by the European Commission and coordinated by the Environment Directorate-General (LIFE Units - E.3. and E.4.). The contents of the publication “LIFE and European Mammals: Improving their conservation status” do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the institutions of the European Union. Authors: João Pedro Silva (Nature expert), András Demeter (DG Environment), Justin Toland, Wendy Jones, Jon Eldridge, Tim Hudson, Eamon O’Hara, Christophe Thévignot (AEIDL, Communications Team Coordinator). Managing Editor: Angelo Salsi (European Commission, DG Environment, LIFE Unit). LIFE Focus series coordination: Simon Goss (DG Environment, LIFE Communications Coordinator), Evelyne Jussiant (DG Environment, Communications Coordinator). The following people also worked on this issue: Frank Vassen (DG Environment). Production: Monique Braem. Graphic design: Daniel Renders, Anita Cortés (AEIDL). Acknowledgements: Thanks to all LIFE project beneficiaries who contributed comments, photos and other useful material for this report. Photos: Unless otherwise specified; photos are from the respective projects. Cover photo: www. luis-ferreira.com; Tiit Maran; LIFE03 NAT/F/000104. HOW TO OBTAIN EU PUBLICATIONS Free publications: • via EU Bookshop (http://bookshop.europa.eu); • at the European Commission’s representations or delegations. You can obtain their contact details on the Internet (http://ec.europa.eu) or by sending a fax to +352 2929-42758. Priced publications: • via EU Bookshop (http://bookshop.europa.eu). Priced subscriptions (e.g. annual series of the Official Journal of the European Union and reports of cases before the Court of Justice of the European Union): • via one of the sales agents of the Publications Office of the European Union (http://publications.europa.eu/ others/agents/index_en.htm). -

Climate Change and Migratory Species Migratory Species

BTO Research Report 414 BTO Research Report 414 Climate Change and Climate Change and Migratory Species Migratory Species Authors Authors Robert A. Robinson1, Jennifer A. Learmonth2, Anthony M. Hutson3, Robert A. Robinson1, Jennifer A. Learmonth2, Anthony M. Hutson3, Colin D. Macleod2, Tim H. Sparks4, David I. Leech1, Colin D. Macleod2, Tim H. Sparks4, David I. Leech1, Graham J. Pierce2, Mark M. Rehfisch1 & Humphrey Q.P. Crick1 Graham J. Pierce2, Mark M. Rehfisch1 & Humphrey Q.P. Crick1 A Report for Defra Research Contract CR0302 A Report for Defra Research Contract CR0302 August 2005 August 2005 1 British Trust for Ornithology, The Nunnery, Thetford, IP24 2PU 1 British Trust for Ornithology, The Nunnery, Thetford, IP24 2PU 2 Department of Zoology, University of Aberdeen, Tillydrone Avenue, Aberdeen, AB24 2TZ 2 Department of Zoology, University of Aberdeen, Tillydrone Avenue, Aberdeen, AB24 2TZ 3 IUCN - SSC Chiroptera Specialist Group 3 IUCN - SSC Chiroptera Specialist Group 4 Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, Monks Wood, Abbots Ripton, Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire, 4 Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, Monks Wood, Abbots Ripton, Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire, PE28 2LS PE28 2LS British Trust for Ornithology, The Nunnery, Thetford, Norfolk, IP24 2PU British Trust for Ornithology, The Nunnery, Thetford, Norfolk, IP24 2PU Registered Charity No. 216652 Registered Charity No. 216652 CONTENTS CONTENTS Page No. Page No. List of Tables, Figures and Appendices .....................................................................................................7 -

The Wild West: Feral Horse Health and Management

Exotics – Wildlife ______________________________________________________________________________________________ THE WILD WEST: FERAL HORSE HEALTH co-evolved with its habitat without human manipulation. AND MANAGEMENT Critics of the idea that the North American wild horse is a native animal, using only paleontological data, assert David Hunter, DVM that the species, E caballus (or the caballoid horse), Turner Enterprises, Inc. which was introduced in 1519, was a different species Turner Endangered Species Fund from that which disappeared 13,000 to 11,000 years Bozeman, MT before. Herein lies the crux of the debate. The Tarpan (Equus ferus ferus) and Przewalski's For the general public there is no debate or any horse (Equus ferus przewalski) are the only two never- negative issues surrounding feral/wild horses on public domesticated "wild" groups that survived into historic lands in the West. The sight of these horses creates an times. The Tarpan became extinct in the 19th century. emotional and passionate sense of the history of the Before its loss, the Tarpan was the most likely ancestor “Wild West.” The public can visualize cowboys herding of the domestic horse and roamed the steppes of cattle on long drives along the Chisholm Trail. Eurasia at the time of domestication. Biologists, ranchers, and scientists see these horses In contrast, the Przewalski's horse was saved from the from a different perspective. The horses considered wild brink of extinction and is now the subject of a recovery by the public were actually brought to North America by program based on reintroductions in Mongolia. If European settlers. When they escaped or were released investment in wild horse conservation is truly important, they became feral.