Boreal and Temperate Forests Differ in Environment, Structure, Composition and Disturbance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

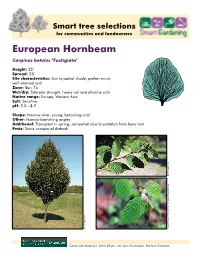

European Hornbeam Carpinus Betulus ‘Fastigiata’

Smart tree selections for communities and landowners European Hornbeam Carpinus betulus ‘Fastigiata’ Height: 35’ Spread: 25’ Site characteristics: Sun to partial shade; prefers moist, well-drained soils Zone: 5a - 7a Wet/dry: Tolerates drought, heavy soil and alkaline soils Native range: Europe, Western Asia Salt: Sensitive pH: 5.0 - 8.2 Shape: Narrow when young, becoming oval Other: Narrow branching angles Additional: Transplant in spring, somewhat slow to establish from bare root Pests: Some occasional dieback Bert Cregg, MSU Bert Cregg, Bert Cregg, MSU Bert Cregg, Bugwood.org Hungary, of West Univ. Norbert Frank, Content development: Dana Ellison, Tree form illustrations: Marlene Cameron. Smart tree selections for communities and landowners Bert Cregg and Robert Schutzki, Michigan State University, Departments of Horticulture and Forestry A smart urban or community landscape has a diverse combination of trees. The devastation caused by exotic pests such as Dutch elm disease, chestnut blight and emerald ash borer has taught us the importance of species diversity in our landscapes. Exotic invasive pests can devastate existing trees because many of these species may not have evolved resistance mechanisms in their native environments. In the recent case of emerald ash borer, white ash and green ash were not resistant to the pest and some communities in Michigan lost up to 20 percent of their tree cover. To promote diverse use of trees by homeowners, landscapers and urban foresters, Michigan State University Extension offers a series of tip sheets for smart urban and community tree selection. In these tip sheets, we suggest trees that should be considered in situations where an ash tree may have been planted in the past. -

The Mediterranean Forests Are Extraordinarily Beautiful, a Fascinating an Extraordinary Patrimony of Wealth Whose Conservation Can Be Highly Controversy

THE editerraneanFORESTS mA NEW CONSERVATION STRATEGY 1 3 2 4 5 6 the unveiled a meeting point the mediterranean: amazing plant an unknown millennia forests on the global 200 the terrestrial current a brand new the state of WWF a new approach wealth of the of nature a sea of forests diversity animal world of human the wane in the sub-ecoregions mediterranean tool: the gap mediterranean in action for forest mediterranean and civilisations interaction with mediterranean in the forest cover analysis forests protection forests forests mediterranean 23 46 81012141617 18 19 22 24 7 1 Argania spinosa fruits, Essaouira, Morocco. Credit: WWF/P. Regato 2 Reed-parasol maker, Tunisia. Credit: WWF-Canon/M. Gunther 3 Black-shouldered Kite. Credit: Francisco Márquez 4 Endemic mountain Aquilegia, Corsica. Credit: WWF/P. Regato 5 Sacred ibis. Credit: Alessandro Re 6 Joiner, Kure Mountains, Turkey. Credit: WWF/P. Regato 7 Barbary ape, Morocco. Credit: A. & J. Visage/Panda Photo It is like no other region on Earth. Exotic, diverse, roamed by mythical WWF Mediterranean Programme Office launched its campaign in 1999 creatures, deeply shaped by thousands of years of human intervention, the to protect 10 outstanding forest sites among the 300 identified through cradle of civilisations. a comprehensive study all over the region. When we talk about the Mediterranean region, you could be forgiven for The campaign has produced encouraging results in countries such as Spain, thinking of azure seas and golden beaches, sun and sand, a holidaymaker’s Turkey, Croatia and Lebanon. NATURE AND CULTURE, of forest environments in the region. But in recent times, the balance AN INTIMATE RELATIONSHIP Long periods of considerable forest between nature and humankind has paradise. -

Grassland & Shrubland Vegetation

Grassland & Shrubland Vegetation Missoula Draft Resource Management Plan Handout May 2019 Key Points Approximately 3% of BLM-managed lands in the planning area are non-forested (less than 10% canopy cover); the other 97% are dominated by a forested canopy with limited mountain meadows, shrublands, and grasslands. See table 1 on the following page for a break-down of BLM-managed grassland and shrubland in the planning area classified under the National Vegetation Classification System (NVCS). The overall management goal of grassland and shrubland resources is to maintain diverse upland ecological conditions while providing for a variety of multiple uses that are economically and biologically feasible. Alternatives Alternative A (1986 Garnet RMP, as Amended) Maintain, or where practical enhance, site productivity on all public land available for livestock grazing: (a) maintain current vegetative condition in “maintain” and “custodial” category allotments; (b) improve unsatisfactory vegetative conditions by one condition class in certain “improvement” category allotments; (c) prevent noxious weeds from invading new areas; and, (d) limit utilization levels to provide for plant maintenance. Alternatives B & C (common to all) Proposed objectives: Manage uplands to meet health standards and meet or exceed proper functioning condition within site or ecological capability. Where appropriate, fire would be used as a management agent to achieve/maintain disturbance regimes supporting healthy functioning vegetative conditions. Manage surface-disturbing activities in a manner to minimize degradation to rangelands and soil quality. Mange areas to conserve BLM special status species plants. Ensure consistency with achieving or maintaining Standards of Rangeland Health and Guidelines for Livestock Grazing Management for Montana, North Dakota, and South Dakota. -

Distribution of Living Cupressaceae Reflects the Breakup of Pangea

Distribution of living Cupressaceae reflects the breakup of Pangea Kangshan Maoa,b,c,1, Richard I. Milnea,b,c,1, Libing Zhangd,e, Yanling Penga, Jianquan Liua,2, Philip Thomasc, Robert R. Millc, and Susanne S. Rennerf aState Key Laboratory of Grassland Agro-Ecosystem, School of Life Sciences, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, Gansu 730000, People’s Republic of China; bInstitute of Molecular Plant Sciences, School of Biological Sciences, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH9 3JH, United Kingdom; cRoyal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH3 5LR, Scotland, United Kingdom; dChengdu Institute of Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Chengdu, Sichuan 610041, People’s Republic of China; eMissouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO 63166; fSystematic Botany and Mycology, Department of Biology, University of Munich, 80638 Munich, Germany Edited by Charles C. Davis, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, and accepted by the Editorial Board March 21, 2012 (received for review September 2, 2011) Most extant genus-level radiations in gymnosperms are of Oligocene occur on all continents except Antarctica and comprise 162 species age or younger, reflecting widespread extinction during climate in 32 genera (see Table S2 for subfamilies, genera, and species cooling at the Oligocene/Miocene boundary [∼23 million years ago numbers). The family has a well-studied fossil record going back (Ma)]. Recent biogeographic studies have revealed many instances of to the Jurassic (32–36). Using ancient fossils to calibrate genetic long-distance dispersal in gymnospermsaswellasinangiosperms. distances in molecular phylogenies can be problematic, because the Acting together, extinction and long-distance dispersal are likely to older a fossil is, the more likely it is to represent an extinct lineage erase historical biogeographic signals. -

Charbrook Nursery

charbrook nursery Plant List Spring-Summer-Autumn 2020 Name Size Wholesale Red Maple 1.5"-2" $200.00 Acer rubrum `Brandywine`, `Frank Jr.`, `Franksred` TM, `Sun Valley` 2"-2.5" $260.00 Single-stem 2.5"-3" $380.00 3"-3.5" $500.00 3.5"-4" $670.00 4"-4.5" $860.00 Sugar Maple 1.5"-2" $250.00 Acer saccharum `Fall Fiesta`, Flashfire 2"-2.5" $300.00 2.5"-3" $380.00 Autumn Blaze Maple 2.5"-3" $360.00 Acer rubrum 'Autumn Blaze' x 'Freemanii' 3"-3.5" $470.00 3.5"-4" $640.00 4"-4.5" $850.00 Shadblow Serviceberry 4'-5' $195.00 Amelanchier x grandiflora 'Autumn Brillance' 5'-6' $240.00 Multi-stem 6'-7' $285.00 7'-8' $420.00 8'-10' $630.00 10'-12' $855.00 Yellow Birch 1"-1.5" $180.00 Betula alleghaniensis 1.5"-2" $250.00 2"-2.5" $350.00 2.5"-3" $460.00 Sweet Birch 1.5"-2" $210.00 Betula lenta 2"-2.5" $300.00 2.5"-3" $400.00 Paper Birch 1.5"-2" $210.00 Betula papyrifera 2"-2.5" $300.00 Betula papyrifera `Varen` 2.5"-3" $400.00 Charbrook Nursery 71 Gates Road Princeton, MA 01541 Page 1 Franz Fontaine Hornbeam 2"-2.5" $320.00 Carpinus betulus `Franz Fontaine` 2.5"-3" $460.00 3"-3.5" $620.00 American Hornbeam 2"-2.5" $300.00 Carpinus caroliniana 2.5"-3" $390.00 3"-3.5" $510.00 Northern Catalpa 2.5"-3" $360.00 Catalpa speciosa 3"-3.5" $470.00 3.5"-4" $690.00 4"-4.5" $900.00 Giant Dogwood 2"-2.5" $280.00 Cornus controversa `June Snow` 2.5"-3" $350.00 Tamarack 10'-12' $400.00 Larix laricina 12'-14' $530.00 (Spring dig only) 14'-16' $710.00 Crab Apple 1.5"-2" $210.00 Malus x `Donald Wyman` , `Schmidtcutleaf` TM, `Snowdrift` 2"-2.5" $260.00 American Hophornbeam -

Hornbeam Carpinus Betulus

34 W I N G E D S E E D S W I N G E D S E E D S 35 Sycamore Acer pseudoplatanus Hornbeam Carpinus betulus Leaves are large and five-lobed, with ornbeams are native trees found largely in south-eastern his introduced species grows in a wide dark green upper range of habitats and soil types. Sycamore sides.The seeds HEngland, with scattered trees in other parts of the country. T come in pairs, that They tolerate a wide range of soils, including sands, gravels and is an excellent coloniser and is often consid- are joined together ered a problem species as, in certain habitats, at an angle. heavy clay, but grow best on damp, fertile soils. Hornbeams including woodland, it can become the domi- produce excellent autumn colours, retaining their leaves throughout much of the winter. nant species. Large tree (5:10:25) Sycamore wood is light in colour, strong and One of the hardest and toughest woods in hard, and is used for kitchen table-tops, floor- Britain, the name hornbeam derives ing, veneers and toys. from the fact that the wood is as This species supports a limited number hard as horn. It was used for of insect species, which includes large cattle yokes, waterwheels and numbers of aphids. In consequence, butchers’ chopping blocks. The migrating warblers can often be found timber also makes excellent fire- feeding in sycamores in the autumn. The wood. tree also supports good lichen growth, Hornbeams are valu- particularly in the west of Britain. able to wildlife, pro- ducing nutlets Seed Guide: Collect the fruits from the which are eaten tree in autumn when they turn by hawfinches brown. -

Understanding the Causes of Bush Encroachment in Africa: the Key to Effective Management of Savanna Grasslands

Tropical Grasslands – Forrajes Tropicales (2013) Volume 1, 215−219 Understanding the causes of bush encroachment in Africa: The key to effective management of savanna grasslands OLAOTSWE E. KGOSIKOMA1 AND KABO MOGOTSI2 1Department of Agricultural Research, Ministry of Agriculture, Gaborone, Botswana. www.moa.gov.bw 2Department of Agricultural Research, Ministry of Agriculture, Francistown, Botswana. www.moa.gov.bw Keywords: Rangeland degradation, fire, indigenous ecological knowledge, livestock grazing, rainfall variability. Abstract The increase in biomass and abundance of woody plant species, often thorny or unpalatable, coupled with the suppres- sion of herbaceous plant cover, is a widely recognized form of rangeland degradation. Bush encroachment therefore has the potential to compromise rural livelihoods in Africa, as many depend on the natural resource base. The causes of bush encroachment are not without debate, but fire, herbivory, nutrient availability and rainfall patterns have been shown to be the key determinants of savanna vegetation structure and composition. In this paper, these determinants are discussed, with particular reference to arid and semi-arid environments of Africa. To improve our current under- standing of causes of bush encroachment, an integrated approach, involving ecological and indigenous knowledge systems, is proposed. Only through our knowledge of causes of bush encroachment, both direct and indirect, can better livelihood adjustments be made, or control measures and restoration of savanna ecosystem functioning be realized. Resumen Una forma ampliamente reconocida de degradación de pasturas es el incremento de la abundancia de especies de plan- tas leñosas, a menudo espinosas y no palatables, y de su biomasa, conjuntamente con la pérdida de plantas herbáceas. En África, la invasión por arbustos puede comprometer el sistema de vida rural ya que muchas personas dependen de los recursos naturales básicos. -

Global Ecological Forest Classification and Forest Protected Area Gap Analysis

United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre Global Ecological Forest Classification and Forest Protected Area Gap Analysis Analyses and recommendations in view of the 10% target for forest protection under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) 2nd revised edition, January 2009 Global Ecological Forest Classification and Forest Protected Area Gap Analysis Analyses and recommendations in view of the 10% target for forest protection under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) Report prepared by: United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC) World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) Network World Resources Institute (WRI) Institute of Forest and Environmental Policy (IFP) University of Freiburg Freiburg University Press 2nd revised edition, January 2009 The United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP- WCMC) is the biodiversity assessment and policy implementation arm of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the world's foremost intergovernmental environmental organization. The Centre has been in operation since 1989, combining scientific research with practical policy advice. UNEP-WCMC provides objective, scientifically rigorous products and services to help decision makers recognize the value of biodiversity and apply this knowledge to all that they do. Its core business is managing data about ecosystems and biodiversity, interpreting and analysing that data to provide assessments and policy analysis, and making the results -

Forests Warranting Further Consideration As Potential World

Forest Protected Areas Warranting Further Consideration as Potential WH Forest Sites: Summaries from Various and Thematic Regional Analyses (Compendium produced by Marc Patry, for the proceedings of the 2nd World Heritage Forest meeting, held at Nancy, France, March 11-13, 2005) Four separate initiatives have been carried out in the past 10 years in an effort to help guide the process of identifying and nominating new WH Forest sites. The first, carried out by Thorsell and Sigaty (1997), addresses forests worldwide, and was developed based on the authors’ shared knowledge of protected forests worldwide. The second focuses exclusively on tropical forests and was assembled by the participants at the 1998 WH Forest meeting in Berastagi, Indonesia (CIFOR, 1999). A third initiative consists of potential boreal forest sites developed by the participants to an expert meeting on boreal forests, held in St. Petersberg in 2003. Finally, a fourth, carried out jointly between UNEP and IUCN applied a more systematic approach (IUCN, 2004). Though aiming at narrowing the field of potential candidate sites, these initiatives do not automatically imply that all of the listed forest areas would meet the criteria for inscription on the WH List, and conversely, nor do they imply that any site left off the list would not meet these criteria. Since these lists were developed, several of the proposed sites have been inscribed on the WH List, while others have been the subject of nominations, but were not inscribed, for various reasons. The lists below are reproduced here in an effort to facilitate access to this information and to guide future nomination initiatives. -

Rainforests and Tropical Diversity

Rainforests and Tropical Diversity Gaby Orihuela Visitor Experience Manager Global Strategy for Plant Conservation Objective IV: Education and awareness about plant diversity, its role in sustainable livelihoods and importance to all life on earth is promoted. – Target 14: The importance of plant diversity and the need for its conservation incorporated into communication, education and public awareness programs. What are Rainforests? Forests characterized by high rainfall, with definitions based on a minimum normal annual rainfall of 68–78 inches, and as much as 390 inches. (Miami receives an average annual of ~60 inches.) Two types: Tropical (wet and warm) and Temperate Around 40% to 75% of all biotic species are indigenous to the tropical rainforests Natural reservoir of genetic diversity and ecological services: – Rich source of medicinal plants – High-yield foods and a myriad of other useful forest products – Sustain a large number of diverse and unique indigenous cultures – Important habitat for migratory animals Peruvian Amazonia Where in the World? Today less than 3% of Earth’s land is covered with these forests (about 2 million square miles). A few thousand of years ago they covered 12% (6 million). Tropical forests are restricted to the latitudes 23.5° North and 23.5° South of the equator, or in other words between the Tropic of Capricorn and the Tropic of Cancer. Global distribution in four biogeographic realms: – Afrotropical (mainland Africa, Madagascar, and scattered islands) – Australian (Australia, New Guinea, and -

Cupressaceae Calocedrus Decurrens Incense Cedar

Cupressaceae Calocedrus decurrens incense cedar Sight ID characteristics • scale leaves lustrous, decurrent, much longer than wide • laterals nearly enclosing facials • seed cone with 3 pairs of scale/bract and one central 11 NOTES AND SKETCHES 12 Cupressaceae Chamaecyparis lawsoniana Port Orford cedar Sight ID characteristics • scale leaves with glaucous bloom • tips of laterals on older stems diverging from branch (not always too obvious) • prominent white “x” pattern on underside of branchlets • globose seed cones with 6-8 peltate cone scales – no boss on apophysis 13 NOTES AND SKETCHES 14 Cupressaceae Chamaecyparis thyoides Atlantic white cedar Sight ID characteristics • branchlets slender, irregularly arranged (not in flattened sprays). • scale leaves blue-green with white margins, glandular on back • laterals with pointed, spreading tips, facials closely appressed • bark fibrous, ash-gray • globose seed cones 1/4, 4-5 scales, apophysis armed with central boss, blue/purple and glaucous when young, maturing in fall to red-brown 15 NOTES AND SKETCHES 16 Cupressaceae Callitropsis nootkatensis Alaska yellow cedar Sight ID characteristics • branchlets very droopy • scale leaves more or less glabrous – little glaucescence • globose seed cones with 6-8 peltate cone scales – prominent boss on apophysis • tips of laterals tightly appressed to stem (mostly) – even on older foliage (not always the best character!) 15 NOTES AND SKETCHES 16 Cupressaceae Taxodium distichum bald cypress Sight ID characteristics • buttressed trunks and knees • leaves -

Description of the Ecoregions of the United States

(iii) ~ Agrl~:::~~;~":,c ullur. Description of the ~:::;. Ecoregions of the ==-'Number 1391 United States •• .~ • /..';;\:?;;.. \ United State. (;lAn) Department of Description of the .~ Agriculture Forest Ecoregions of the Service October United States 1980 Compiled by Robert G. Bailey Formerly Regional geographer, Intermountain Region; currently geographer, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station Prepared in cooperation with U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and originally published as an unnumbered publication by the Intermountain Region, USDA Forest Service, Ogden, Utah In April 1979, the Agency leaders of the Bureau of Land Manage ment, Forest Service, Fish and Wildlife Service, Geological Survey, and Soil Conservation Service endorsed the concept of a national classification system developed by the Resources Evaluation Tech niques Program at the Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, to be used for renewable resources evaluation. The classifica tion system consists of four components (vegetation, soil, landform, and water), a proposed procedure for integrating the components into ecological response units, and a programmed procedure for integrating the ecological response units into ecosystem associations. The classification system described here is the result of literature synthesis and limited field testing and evaluation. It presents one procedure for defining, describing, and displaying ecosystems with respect to geographical distribution. The system and others are undergoing rigorous evaluation to determine the most appropriate procedure for defining and describing ecosystem associations. Bailey, Robert G. 1980. Description of the ecoregions of the United States. U. S. Department of Agriculture, Miscellaneous Publication No. 1391, 77 pp. This publication briefly describes and illustrates the Nation's ecosystem regions as shown in the 1976 map, "Ecoregions of the United States." A copy of this map, described in the Introduction, can be found between the last page and the back cover of this publication.