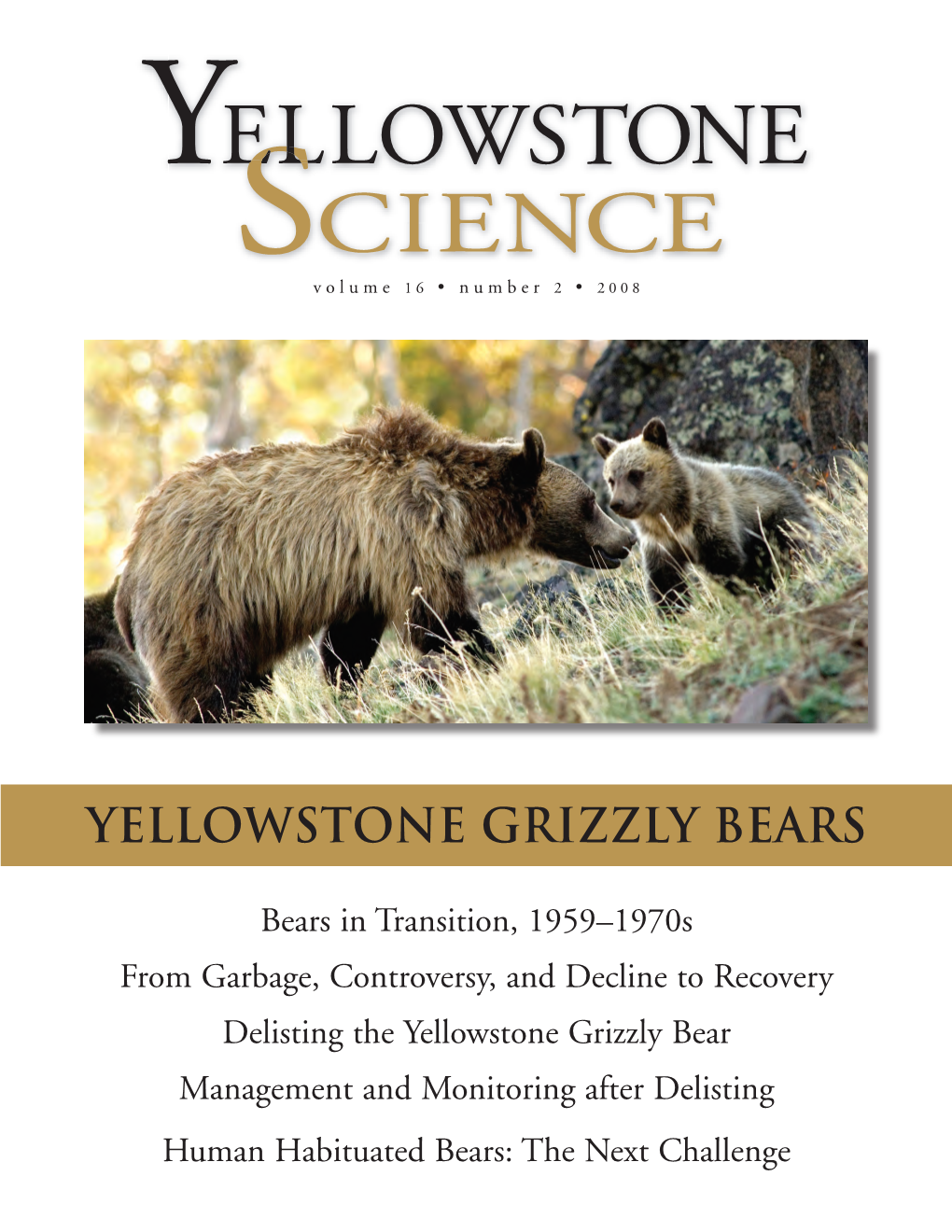

Yellowstone Grizzly Bears

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advertising Guidelines

ADVERTISING 2020 GUIDELINES The Minnesota Deer Hunters Association (MDHA) is a grassroots conservation organization dedicated to building our hunting and conservation legacy through habitat, education and advocacy. As you may be aware, MDHA originated from a small group of concerned hunters that wanted to look out for the betterment of deer and the sport of deer hunting. MDHA has now evolved into a nearly 20,000 member community of deer and deer hunting advocates. We share the commonality and enjoy the camaraderie of ensuring the future of deer and deer hunting in Minnesota. What has MDHA done since 1980? MDHA’s Hides for Habitat Program has recycled nearly 865,000 deer hides; raising $5.23 MILLION for habitat restoration, public hunting land acquisition and youth education projects. Through local chapter fundraising MDHA’s 60 chapters across the state raise nearly ONE MILLION dol- lars annually supporting local habitat and hunting education and recruitment programs in Minnesota for Minne- sota. Since 1996 MDHA has enhanced public lands to a tune of OVER $43 MILLION in habitat projects. Since 1985 nearly 11,000 kids have been sent to our week-long MDHA Forkhorn Camp ® providing hands on firearms safety, bow safety, and advanced hunter education. Here are some quick stats about MDHA members: Our members have a mean income of $91,000 86% of members hunt on private land The second and third most popular activities amongst members after hunting is fishing and ice fishing Our mean membership age is 55 years of age 72% of members own -

Grizzly Bear Fact Sheet

Identify Grizzly from Black Bears Grizzly bears typically weigh 100-200 kg (females) to 200-300 kg (males) which is slightly more than black bears. Grizzly bears have a shoulder hump, range in colour from blonde to black and may have silver or light- tipped guard hairs on their head, hump and back. A grizzly bear’s ears are rounded and appear smaller than the black bear, while the black bear has more pointed, noticeable ears and no shoulder hump. Grizzly bear claws are longer than those of black bears and may have a light-coloured stripe. In grizzly bear ISBN: 978-0-7785-8683-8 (Printed Version) tracks, the tips of the front claws usu- 978-0-7785-8683-8 (Online Version) ally leave imprints in front of the paw Printed July 2009 pad, and the toes are set in a nearly straight line. In black bear tracks, the claw imprints are difficult to see, and the front toes form an obvious arc. Reproduction Range Grizzly bear numbers are limited by a slow reproductive rate. This is Grizzly bears can be found caused by a relatively high age of first reproduction, small litter siz- in Alberta from the Montana es, and long periods between litters. In Alberta, most female grizzlies border, along the mountains do not have their first litter until they are at least four years old and and foothills and continuing usually have only one or two cubs. The cubs are born in January or north through the western February and stay with their mother for two to five years. -

Grizzly Bears Arrive at Central Park Zoo Betty and Veronica, the fi Rst Residents of a New Grizzly Bear Exhibit at the Central Park Zoo

Members’ News The Official WCS Members’ Newsletter Mar/Apr 2015 Grizzly Bears Arrive at Central Park Zoo Betty and Veronica, the fi rst residents of a new grizzly bear exhibit at the Central Park Zoo. escued grizzly bears have found a new home at the Betty and Veronica were rescued separately in Mon- RCentral Park Zoo, in a completely remodeled hab- tana and Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming. itat formerly occupied by the zoo’s polar bears. The Both had become too accustomed to humans and fi rst two grizzlies to move into the new exhibit, Betty were considered a danger to people by local authori- and Veronica, have been companions at WCS’s Bronx ties. Of the three bears that arrived in 2013, two are Zoo since 1995. siblings whose mother was illegally shot, and the third is an unrelated bear whose mother was euthanized by A Home for Bears wildlife offi cials after repeatedly foraging for food in a Society Conservation Wildlife © Maher Larsen Julie Photos: The WCS parks are currently home to nine rescued residential area. brown bears, all of whom share a common story: they “While we are saddened that the bears were or- had come into confl ict phaned, we are pleased WCS is able to provide a home with humans in for these beautiful animals that would not have been the wild. able to survive in the wild on their own,” said Director of WCS City Zoos Craig Piper. “We look forward to sharing their stories, which will certainly endear them in the hearts of New Yorkers. -

How People Should Respond When Encountering a Large Carnivore: Opinions of Wildlife Professionals Dy L a N E

Human–Wildlife Conflicts 2(2):194–199, Fall 2008 How people should respond when encountering a large carnivore: opinions of wildlife professionals DYLA N E. BRO wn , 507 Silo Loop, Kinsey, Montana 59338, USA [email protected] MI C HAEL R. CO N OVER , Jack H. Berryman Institute, Department of Wildland Resources, Utah State University, Logan, Utah 84322-5230, USA Abstract: We conducted telephone surveys of wildlife professionals who work with large carnivores to ask their opinions about how people should respond to avoid being injured when confronted by a black bear (Ursus americana), grizzly bear (Ursus arctos), mountain lion (Puma concolor), or gray wolf (Canis lupus). The respondents agreed that the most appropriate response was to try to increase the distance between a person and the carnivore. In the event of an attack by a black bear, mountain lion, or wolf, most respondents said to fight back. Opinion was divided over the best response for an individual who was being attacked by a grizzly bear, but a slight majority of professionals said to fight back if the attack was predatory and be passive if the attack was defensive; however, respondents also noted that many victims would be unable to identify the bear’s motive. If a black bear came into camp, most respondents said that a person should aggressively encourage the bear to leave and to fight back against a bear that enters a tent at night, regardless of species. Respondents unanimously agreed that bear pepper-spray is effective in defending against an attack. While any encounter with a large carnivore can be fatal to the person involved, we believe that selecting the right course of action increases the odds that the victim can escape without injury. -

Banners in Heraldic Art

Banners in heraldic art Magnus Backrnark Abstract The banner is very useful to heraldic art. It is a carrier of charges and colours, just like its coun terpart the shield. But where the shield can be seen as crude, heavy, flat and robust - its purpose being taking hits- the banner is brilliant, swift, full of I ife and motion. Its purpose is spiritual. It is lifted above anyone's head, above dust and confusion, for inspiration and guiding. Something of this character, I will with this article try to show by examples that the heraldic artist, if lucky, can translate in his or her work. First, we could though take a quick glance at the historical development of banners. The term banner approves, as we shall see, to a specific kind of flag, but in a wide sense of the word a banner is any ensign made of a peace of cloth, carried on a staff and with symbolic value to its owner(s). The profound nature of this innovation, which seem to be of oriental origin, makes it the mother of all kinds of flags. The etymologi cal root of the word banner is the French word banniere, derived from latin bandaria, bandum, which has German extraction, related to gothic bandwa, bandw6, 'sign'. 1 The birth of heraldry in the l2 h century Western world was preceded by centuries of use of early forms of banners, called gonfanons. From Bysantium to Normandy, everywhere in the Christian world, these ensigns usually were small rectangular lance flags with tai Is (Fig. -

Predation by a Golden Eagle on a Brown Bear Cub

SHORT COMMUNICATION N Sørensen et al. Predation by a golden eagle on a brown bear cub Ole J. Sørensen1,4, Mogens Totsa˚ s2, Tore eagles attending bears. Murie hypothesized that Solstad2, and Robin Rigg3 eagles attending bears were waiting for opportunities to capture prey trying to escape from the bears. He 1North-Trondelag University College, Department of also observed eagles swooping at and diving low over Natural Resource Sciences and Information Technology, grizzlies and other carnivores, but interpreted this Box 2501, N-7729 Steinkjer, Norway behavior as play or curiosity, rather than predation. 2 Norwegian Nature Inspectorate, N-7485 Trondheim, C. McIntyre (US National Park Service, Fair- Norway 3 banks, Alaska, USA, personal communication, 2008), Slovak Wildlife Society, PO Box 72, 033 01 Liptovsky a golden eagle researcher in Denali National Park for Hradok, Slovakia many years, has never seen an eagle attack a bear, although she has often observed eagles following Abstract: During spring 2004 an adult female brown bears in open terrain, perhaps positioning themselves bear (Ursus arctos) and her 3 cubs-of-the-year were to take prey escaping from the bear as suggested by observed outside their den on a south-facing low- Murie. Commensalistic hunting, as well as curious or alpine slope in central Norway. They remained near play behavior by eagles in the vicinity of bears, could the den for 8–10 days and were, except for one day, be misinterpreted as eagles hunting, attacking, or observed daily by Totsa˚s and other wardens of the inspecting bears as possible prey. Predation by eagles Norwegian Nature Inspectorate. -

The Effects of the Lake Trout Introduction in Yellowstone Lake on Populations Outside the Aquatic a Meta-Analytic Study

Migrate, Mutate, or Die: The effects of the lake trout introduction in Yellowstone Lake on populations outside the aquatic A Meta-Analytic Study By Sarah Z. Gandhi-Besbes University of Colorado at Boulder A thesis submitted to the University of Colorado at Boulder in partial fulfilment of the requirements to receive Honours designation in Environmental Studies May 2016 Thesis Advisors: Alexander Cruz, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Committee Chair Dale Miller, Environmental Studies Andrew Martin, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology © 2016 by Sarah Z. Gandhi-Besbes All rights reserved i Abstract Yellowstone National Park is a relatively pristine ecosystem preserved through time. The Yellowstone cutthroat trout Oncorhynchus clarkii bouvieri population, inhabiting shallower waters in Yellowstone Lake and spawning in its tributaries, has been declining primarily due to the introduction of a predatory fish. The lake trout Salvelinus namaycush, which rapidly grow to large sizes, feed on the Yellowstone cutthroat trout, breed and spawn in Yellowstone Lake, and dwell in deeper waters out of predatory reach. The Yellowstone cutthroat trout is relied upon both directly and indirectly by more than 40 species within Yellowstone National Park. The grizzly bear Ursus arctos horribilis, bald eagle Haliaeetus leucocephalus, and osprey Pandion halaetus all feed directly on the spawning fish. This study looks at how the declining Yellowstone cutthroat trout populations affect these predatory populations, and what their populations may look like should current trends continue into the year 2030. Conducting a meta-analysis and collecting primary data allowed for statistical projections predicting and comparing estimated future populations. The ecological change in Yellowstone Lake provides insight into how the concerns of one ecosystem affects multiple. -

Yellowstone Grizzly Bears: Ecology and Conservation of an Icon of Wildness

YELLOWSTONE GRIZZLY BEARS ecology and conservation of an ICON OF WILDNESS EDITED BY P.J. White, Kerry A. Gunther, and Frank T. van Manen YELLOWSTONE GRIZZLY BEARS Yellowstone Grizzly Bears: Ecology and Conservation of an Icon of Wildness Editors P. J. White, Kerry A. Gunther, and Frank T. van Manen Contributing Authors Daniel D. Bjornlie, Amanda M. Bramblett, Steven L. Cain, Tyler H. Coleman, Jennifer K. Fortin-Noreus, Kevin L. Frey, Mark A. Haroldson, Pauline L. Kamath, Eric G. Reinertson, Charles T. Robbins, Daniel J. Thompson, Daniel B. Tyers, Katharine R. Wilmot, and Travis C. Wyman Managing Editor Jennifer A. Jerrett YELLOWSTONE FOREVER, YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK AND U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY, NORTHERN ROCKY MOUNTAIN SCIENCE CENTER Yellowstone Forever, Yellowstone National Park 82190 Published 2017 Contents Printed in the United States of America All chapters are prepared solely by officers or employees of the United States Preface ix government as part of their official duties and are not subject to copyright protection Daniel N. Wenk, Superintendent, Yellowstone National Park in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply. National Park Service (NPS) photographs are not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign Introduction xv copyrights may apply. However, because this work may contain other copyrighted images or other incorporated material, permission from the copyright holder may be P. J. White, Kerry A. Gunther, and Frank T. van Manen necessary. Cover and half title images: www.revealedinnature.com by Jake Davis. Chapter 1: The Population 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data P. J. White, Kerry A. Gunther, and Travis C. -

47 C. OTHER FEDERALLY LISTED SPECIES WITHIN the RANGE SPOTTED OWL 47 Oregon Silverspot Butterfly 47 Aleutian Canada Goose 48

47 C. OTHER FEDERALLY LISTED SPECIES WITHIN THE RANGE SPOTTED OWL 47 Oregon Silverspot Butterfly 47 Aleutian Canada Goose 48 Bald Eagle 49 Peregrine Falcon 50 Gray Wolf 50 Grizzly Bear 51 Columbian White-tailed Deer C. Other Fe Range of the No Nine wildlife species within the range of the northern spotted owl are listed by the federal government as threatened or endangered: the northern spotted owl, marbled murrelet, Oregon silverspot butterfly, Aleutian Canada goose, bald eagle, peregrine falcon, gray wolf, grizzly bear, and Columbian white-tailed deer. Discussions of species ecology for the spotted owl and marbled murrelet are found in Sections A and B of this chapter, respectively. Habitat needs of the other seven species are reviewed below, followed by Table 111.8, which lists for each of the nine species its federal and state status and in which HCP planning unit each could potentially occur. on Silvers The Oregon silverspot butterfly (Speyeria zerene hippolyta) is the only federally listed species of arthropod that is found in Washington (WDW 1993a). This butterfly is currently listed by the federal government as threatened and by the state as endangered. However, no critical habitat in I Washington has been designated under the Endangered Species Act (WDW 1993b). The Oregon silverspot is found only in habitats that support its larval host plant, western blue violet (Viola adunca). Such habitats include coastal salt-spray meadows and open fields. In Washington, potential habitat for the Oregon silverspot is limited to the coastal grasslands on the Long Beach peninsula near Loomis Lake (WDW 199313; WDW 1991).Adult butterflies are thought to rest and feed in adjacent open spruce/shoreline pine forest glades, where they are protected from wind and can feed on nectar available from a number of plant species. -

Qdma's Whitetailreport 2020

DEER HARVEST TRENDS qdma ’s PART 1: WhitetailReport 2020 An annual report on the status of white-tailed deer – the foundation of the hunting industry in North America Compiled and Written by the QDMA Staff Field to Fork mentor Charles Evans (right) congratulates Andy Cunningham on his first deer. WhitetailReport Special thanks to all of these QDMA Sponsors, Partners and Supporters for helping enable our mission: ensuring the future of white-tailed deer, wildlife habitat and our hunting heritage. Please support these companies that support QDMA. For more information on how to become a corporate supporter of QDMA, call 800-209-3337. Sponsors Partners Rec onnect w ith Real F ood Supporters 2 • QDMA's Whitetail Report 2020 QDMA.com • 3 WhitetailReport QDMA MISSION: TABLE OF CONTENTS QDMA is dedicated to ensuring the future of white-tailed deer, wildlife PART 1: DEER HARVEST TRENDS PART 3: QDMA MISSION & ANNUAL REPORT habitat and our hunting heritage. Antlered Buck Harvest ....................................................6 QDMA: Ensuring the Future of Deer Hunting ................40 QDMA NATIONAL STAFF Age Structure of the Buck Harvest ..................................8 2019 QDMA Advocacy Update ......................................41 Antlerless Deer Harvest ................................................10 QDMA Mission: Progress Report ...................................42 Chief Executive Officer Age Structure of the Antlerless Harvest ........................12 QDMA Communications Update ...................................43 Brian -

Supporter Care Executive (Volunteer Support Group Lead - UK)

Supporter Care Executive (Volunteer Support Group lead - UK) Jan 2021 Join the family … be part of the end game Contents Letter from the Global Director of Supporter Insights & Experience 3 About Us 4 Dept. Structure 5 Job Description 6 Person Specification 9 Conditions and Benefits 11 Recruitment schedule and how to apply 12 Page | 2 Welcome to Animals Asia I’m delighted to introduce you to Animals Asia, a progressive, dynamic and global organisation making great advances in animal welfare predominantly in China and Vietnam, but with reach across Asia. If you are looking for a career move that will enable you to play a key role in creating significant, lasting change you will be excited about working here. In 1998, we set out with a primary goal of ending bear bile farming – a horrific trade that is arguably the world’s cruelest form of animal abuse. In 2017, the Vietnamese Government announced its partnership with Animals Asia to bring this to an end by 2022. This year, we will be raising funds to build a new sanctuary in Vietnam so we can bring the last the country’s bile bears home. There has never been a more exciting time to join the team and be part of this historic, rewarding journey. We are also at the forefront of ending elephant riding in Vietnam – a model which we hope can be rolled out across the rest of Asia. Our fundraising team is equally progressive and exciting. You will be joining an exceptionally talented, passionate and dedicated group of people and have the ambition to match our potential. -

20214Hfairbook.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS SHORTER MEMORIAL BEEF EXHIBITOR AWARD 3 ED FISHER MEMORIAL LIVESTOCK EXHIBITOR AWARD 3 4-H AND YOUTH DEPARTMENT SCHEDULE 4 2021 FAIR CHANGES 7 4-H AND YOUTH DEPARTMENT GENERAL RULES 8 2021 LIVESTOCK HEALTH REQUIREMENTS 11 GENERAL LIVESTOCK RULES 13 MARKET LIVESTOCK SALE 17 BEEF CATTLE AND BUCKET CALF 18 DIVISION - BUCKET CALF 18 MARKET BEEF RATE OF GAIN CONTEST 20 SWINE 21 SHEEP 22 MARKET LAMB RATE OF GAIN CONTEST 23 DAIRY CATTLE 24 HORSE 26 GRAND CHAMPION SHOWMAN/ROUND ROBIN CONTEST 29 DAIRY GOATS 30 MEAT GOATS 32 MARKET MEAT GOAT RATE OF GAIN CONTEST 32 POULTRY/PIGEONS 34 RABBITS 36 LIVESTOCK SPECIAL AWARDS 38 FIELD CROPS 41 HORTICULTURE/FLORICULTURE 43 FORESTRY 45 VISUAL ARTS 48 HERITAGE/FIBER ARTS 49 CLOTHING CONSTRUCTION 50 FASHION REVUE 52 FOOD AND NUTRITION 55 FOOD PRESERVATION 57 4-H BANNER - PROMOTION - BARN QUILT 60 NOTEBOOKS, PROJECT DISPLAYS, POSTERS 62 ENERGY MANAGEMENT 64 ENTOMOLOGY 67 GEOLOGY 72 PHOTOGRAPHY 75 SPACE TECH 78 4-H STEM EDUCATIONAL EXHIBITS – POSTERS, NOTEBOOKS AND DISPLAY BOARDS 94 WOODWORK 97 DOG SHOW 98 AGRICULTURAL MECHANICS PROJECTS 100 CLOVERBUDS 104 LIVESTOCK JUDGING CONTEST 106 AGRICULTURAL CHALLENGE OF CHAMPIONS 107 2 SHORTER MEMORIAL BEEF EXHIBITOR AWARD Junior Shorter was an influential supporter of Cowley County youth beef programs. He was instrumental in initiating and organizing the Cowley County Classic Beef Show garnering great support from local businesses and supporters. The Cowley County Classic was one of the original and premiere spring beef shows for youth, attracting exhibitors from all over Kansas as well as Oklahoma and Texas.