Ideology, Nationalism, and the FIFA World Cup

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Critical Discourse Analysis of Artur Mas's Selected

Raymond Echitchi “Catalunya no és Espanya”: A critical discourse... 7 “CATALUNYA NO ÉS ESPANYA”: A CRITICAL DISCOURSE ANALYSIS OF ARTUR MAS’S SELECTED SPEECHES Raymond Echitchi, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: This article is a Critical Discourse Analysis of secessionist discourse in Catalonia in the light of a selection of speeches given by Artur Mas. This work aims at deciphering the linguistic strategies used by Mas to construct a separate Catalan identity in three of his speeches, namely his acceptance, inauguration and 2014 referendum speeches. The analysis of these speeches was carried out in the light of Ruth Wodak’s Discourse-historical Approach to Critical Discourse and yielded the identification of three sets strategies to which Artur Mas mostly resorts; singularisation and autonomisation strategies, assimilation and cohesivation strategies and finally continuation strategies. Keywords: Catalonia, sub-state nationalism, secessionism, Critical Discourse Analysis. Resumen: Este artículo analiza, mediante el Análisis Crítico del Discurso, las disertaciones secesionistas en Cataluña de los discursos de Artur Mas. En este trabajo, se pretende captar las estrategias lingüísticas utilizadas por Mas para construir una identidad catalana separada en tres discursos que presentó; en su investidura, su toma de posesión y antes de celebrar el referéndum de 2014. El análisis de estos discursos se llevó a cabo a la luz de la aproximación histórica discursiva de Ruth Wodak y dio lugar a la identificación de tres tipos de estrategias en estos discursos: las estrategias de singularización y autonomización, las estrategias de asimilación y cohesión y las estrategias de continuidad. Palabras clave: Cataluña, nacionalimo sub-estatal, secesionismo, Análisis Crítico del Discurso. -

CEO Succession Planning and Leadership Development- Corporate Lessons from FC Barcelona

International Journal of Managerial Studies and Research (IJMSR) Volume 1, Issue 2 (July 2013), PP 45-49 www.arcjournals.org CEO Succession Planning and Leadership Development- Corporate Lessons from FC Barcelona Amanpreet Singh Chopra Phd. Research Scholar, UPES, India Abstract: Author studied the development program(s) and leadership succession planning strategies of FC Barcelona, one the most successful club in Spanish Football history and analyzed that success of club is deeply rooted in its strategies from grooming of homegrown talent at La Masia to the appointment of coaching staff. Taking cue from club strategies author identified 5 lessons for Corporate- Developing organizational belief in growth strategies, Developing young executive through structured T&D programs, Present career progression opportunities to young employees, Develop „inward‟ succession planning framework through grooming in-house talent and above all nurturing the philosophy of “Más que una empresa”(More than a company). Key Words: Succession Planning, Leadership Development, Sports Psychology 1. FC BARCELONA Futbol Club Barcelona also known as FC Barcelona and familiarly as Barça, is a professional football club, based in Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain. Founded in 1899 by a group of Swiss, English and Catalan footballers led by Joan Gamper, the club has become a symbol of Catalan culture and Catalanism, hence the motto "Més que un club" (More than a club). It is the world's second-richest football club in terms of revenue, with an annual turnover of €398 million (2011). The unique feature of the club is that unlike many other football clubs, the supporters own and operate Barcelona. Jack Greenwell was the first fulltime club manager from 1917 to 1924 under which club grabbed 6 tournament honors. -

Eric Zener Personal 1966 Born, Astoria, Oregon Education 1988

Eric Zener 9/12/2017 Personal 1966 born, Astoria, Oregon Education 1988 University of California, Santa Barbara, BA Selected Solo Exhibitions 2014 Gallery Henoch New York, NY 2013 Gallery Henoch New York, NY 2011 Turner Carroll Gallery, Stay ZaZa Dallas ,Texas Hespe Gallery San Francisco, CA Gallery Henoch New York, NY Long Beach Museum of Art Long Beach, CA Transamerica Pyramid Center San Francisco, CA 2010 Gallery Henoch New York, NY Dieffe Arte Contempotanea Turin, Italy Persterer Fine Art Zurich, Switzerland 2009 Hespe Gallery San Francisco, CA Gallery Henoch New York, NY S.C.A.P.E. Los Angeles, CA 2008 Gallery Henoch New York, NY Hespe Gallery San Francisco, CA Spur Projects Woodside, CA 2007 Gallery Henoch New York, NY Hespe Gallery San Francisco, CA 2006 Hespe Gallery/Bank of America San Francisco, CA Gallery Henoch New York, NY 2005 Hespe Gallery San Francisco, CA Gallery Henoch New York, NY S.C.A.P.E. Los Angeles, CA 2004 Gallery Henoch New York, NY 2003 Hespe Gallery San Francisco, CA 2002 Gallery Henoch New York, NY Diane Nelson Fine Art Laguna Beach, CA Hespe Gallery San Francisco, CA 2001 LewAllen Contemporary Santa Fe, NM Hespe Gallery San Francisco, CA 2000 Hespe Gallery San Francisco, CA Casa Forestal St. Marti de Empuries, Spain 1999 Hespe Gallery San Francisco, CA 1998 Hespe Gallery San Francisco, CA 1997 Hespe Gallery San Francisco, CA continued Selected Solo Exhibitions continued 1997 California Arts Council Sacramento, CA Alfabia Museum Sumoto, Japan Galleria Prova Tokyo, Japan 1996 Hespe Gallery San Francisco, CA 1995 Hespe Gallery San Francisco, CA 1994 Hespe Gallery San Francisco, CA 1990 Gerald Steven’s Fine Art Los Angeles, CA Selected Group Exhibitions 2012 "Contemporary Terrain," Turner Carroll Gallery Santa Fe, NM 2011 Albemarle Gallery London, UK Imago Gallery Palm Desert, CA SF Intl. -

¿Qué Publican Los Diarios Impresos? El Caso Ciudad Victoria, Tamaulipas, México

RAZÓN Y PALABRA Primera Revista Electrónica en América Latina Especializada en Comunicación www.razonypalabra.org.mx ¿QUÉ PUBLICAN LOS DIARIOS IMPRESOS? EL CASO CIUDAD VICTORIA, TAMAULIPAS, MÉXICO Carlos David Santamaría Ochoa 1 Resumen Los medios impresos en Ciudad Victoria, capital del estado mexicano de Tamaulipas incluyen en sus ediciones cotidianas trabajos periodísticos de interés general, sin embargo, los mismos se centran en dos géneros: noticia o nota informativa y columna, lo que se pone de manifiesto en cada una de sus ediciones. Una revisión de los periódicos diarios impresos en sus secciones locales revela que géneros como la crónica, el reportaje o la entrevista son escasos: el periodista se centra en la elaboración de noticias breves y piezas de opinión. La revisión en dos espacios de tiempo nos muestra la forma en que se desarrolla el periodismo en Ciudad Victoria, Tamaulipas, México, destacando la ausencia de la entrevista periodística como género, así como crónicas y artículos. Palabras Clave Periódicos diarios, géneros periodísticos, noticias Abstract The print media in Ciudad Victoria, capital of Tamaulipas state include in its daily editions of general interest journalism, however, they are focused on two genres: news or statement and column, which is evident in each one of its editions. A review of the printed daily newspapers reveals that gender and chronic or interview is limited, as the journalist focuses on the development of short news and opinion pieces. The review in two time slots shows how journalism is developed in Ciudad Victoria, Tamaulipas, Mexico, highlighting the absence of gender newspaper interview as well as reports and articles. -

A Lesson in Humility

A Lesson in Humility There was so much to admire in Spain’s journey to the summi of world football during the 2010 World Cup: Vicente Del Bosque’s wise management, Xavi’s brilliant orchestration of the play, Andrés Iniesta’s incisive running with the ball, David Villa’s prowess in front of goal, and the goalkeeping exploits of Iker Casillas. But for those of us who observed the current World and European champions at close quarters, it was not only their football ability that impressed. Their human qualities, in particular the humility displayed by many of the Spanish players, gained them respect beyond their technical achievements. Was this positive behaviour just a lucky coincidence or was it the result of a culture within the Spanish game? It is easy to see that this successful generation of Spanish footballers are modest, unpretentious and happy to promote a “we” mentality. As Xavi stated during the World Cup: “We are a group of very normal, very hard working people who love the game.” The same can be said of their head coach, Vicente Del Bosque, who has won both the UEFA Champions League and the World Cup with his respectful, patient and unassuming style of management. What is not on public display is the process which has nurtured many of these gifted players, young men who have their feet firmly on the ground. As Fernando Hierro, sports director at the Spanish FA (the RFEF), and Ginés Meléndez, RFEF coaching school director, informed the participants at UEFA’s recent national coaches conference in Madrid, the aim in Spain is to educate talented youngsters to play, to compete and to develop a psychological balance. -

Soccer, Culture and Society in Spain

Soccer, Culture and Society in Spain Spanish soccer is on top of the world, at both international and club levels, with the best teams and a seemingly endless supply of exciting and stylish players. While the Spanish economy struggles, its soccer flourishes, deeply embedded throughout Spanish social and cultural life. But the relationship between soccer, culture and society in Spain is complex. This fascinating, in-depth study shines new light on Spanish soccer by examining the role this sport plays in Basque identity, consol- idated in Athletic Club of Bilbao, the century-old soccer club located in the birthplace of Basque nationalism. Athletic Bilbao has a unique player-recruitment policy, allowing only Basque- born players or those developed at the youth academies of Basque clubs to play for the team, a policy that rejects the internationalism of contemporary globalized soccer. Despite this, the club has never been relegated from the top division of Spanish soccer. A particularly tight bond exists between the fans, their club and the players, with Athletic representing a beacon of Basque national identity. This book is an ethnography of a soccer culture where origins, ethnicity, nationalism, gender relations, power and passion, life-cycle events and death rituals gain new meanings as they become, below and beyond the playing field, a matter of creative contention and communal affirmation. Based on unique, in-depth ethnographic research, Soccer, Culture and Society in Spain investigates how a soccer club and soccer fandom affect the life of a community, interweaving empirical research material with key contemporary themes in the social sciences, and placing the study in the wider context of Spanish political and sporting cultures. -

Constructing Contemporary Nationhood in the Museums and Heritage Centres of Catalonia Colin Breen*, Wes Forsythe**, John Raven***

170 Constructing Contemporary Nationhood in the Museums and Heritage Centres of Catalonia Colin Breen*, Wes Forsythe**, John Raven*** Abstract Geographically, Spain consists of a complex mosaic of cultural identities and regional aspirations for varying degrees of autonomy and independence. Following the end of violent conflict in the Basque country, Catalonia has emerged as the most vocal region pursuing independence from the central Spanish state. Within the Catalan separatist movement, cultural heritage sites and objects have been appropriated to play an intrinsic role in supporting political aims, with a variety of cultural institutions and state-sponsored monumentality playing an active part in the formation and dissemination of particular identity-based narratives. These are centred around the themes of a separate and culturally distinct Catalan nation which has been subject to extended periods of oppression by the varying manifestations of the Spanish state. This study addresses the increasing use of museums and heritage institutions to support the concept of a separate and distinctive Catalan nation over the past decade. At various levels, from the subtle to the blatant, heritage institutions are propagating a message of cultural difference and past injustice against the Catalan people, and perform a more consciously active, overt and supportive role in the independence movement. Key words: Catalonia, museums, heritage, identity, nationhood Across contemporary Europe a range of nationalist and separatist movements are again gaining momentum (Borgen 2010). From calls for independence in Scotland and the divisive politics of the Flemish and Walloon communities in Belgium, to the continually complicated political mosaic of the Balkan states, there are now a myriad of movements striving for either greater or full autonomy for their region or peoples. -

Who Can Replace Xavi? a Passing Motif Analysis of Football Players

Who can replace Xavi? A passing motif analysis of football players. Javier Lopez´ Pena˜ ∗ Raul´ Sanchez´ Navarro y Abstract level of passing sequences distributions (cf [6,9,13]), by studying passing networks [3, 4, 8], or from a dy- Traditionally, most of football statistical and media namic perspective studying game flow [2], or pass- coverage has been focused almost exclusively on goals ing flow motifs at the team level [5], where passing and (ocassionally) shots. However, most of the dura- flow motifs (developed following [10]) were satis- tion of a football game is spent away from the boxes, factorily proven by Gyarmati, Kwak and Rodr´ıguez passing the ball around. The way teams pass the to set appart passing style from football teams from ball around is the most characteristic measurement of randomized networks. what a team’s “unique style” is. In the present work In the present work we ellaborate on [5] by ex- we analyse passing sequences at the player level, us- tending the flow motif analysis to a player level. We ing the different passing frequencies as a “digital fin- start by breaking down all possible 3-passes motifs gerprint” of a player’s style. The resulting numbers into all the different variations resulting from labelling provide an adequate feature set which can be used a distinguished node in the motif, resulting on a to- in order to construct a measure of similarity between tal of 15 different 3-passes motifs at the player level players. Armed with such a similarity tool, one can (stemming from the 5 motifs for teams). -

Tarifas ÍNDICE

Tarifas ÍNDICE PAPEL 3 DIGITAL 7 TELEVISIÓN 9 L’ESPORTIU PAPEL 14 DIGITAL 17 PAPEL 19 PAPEL 19 DIGITAL 22 PAPEL 19 PAPEL 24 CONDICIONES DE CONTRATACIÓN 26 [ 2 ] líder de la prensa en catalán Edición Comarcas Gerundenses Difusión OJD: 9.164 ejemplares Edición Audiencia EGM: 55.000 lectores Barcelona, Tarragona y Lleida Difusión OJD: 13.632 ejemplares Audiencia EGM: 62.000 lectores Cataluña Difusión OJD: 22.796 ejemplares Audiencia EGM: 117.000 lectores Fuente EGM: Febrero 2016 - Noviembre 2016 Fuentes OJD: Julio 2015 - Junio 2016 [ 3 ] el mejor perfil comercial 14-64 años, de clase alta y media alta Edad Clase social Media baja, Baja de 14 a 24 años 11,7% 6,4% + de 64 años 30,9% Alta, Media alta 44,3% de 25 a 64 años 62,6% Media 43,9% Clase alta y media alta Más porcentaje de EL PUNT AVUI 44,3% clases altas vs. periódicos de información general Lectores de peri ódicos de informaci ón general de pago 36,5% Fuentes EGM: Febrero 2016 - Noviembre 2016 [ 4 ] TARIFAS EL PUNT AV UI ifas ar T CATALUÑA CATALUÑA GIRONA BARCELONA* EDICIONES** MENOS GIRONA PÁGINA LABORABLES DOMINGOS LABORABLES DOMINGOS LABORABLES DIUMENGES LABORABLES DOMINGOS LABORABLES DOMINGOS Par 9.095 € 10.914 € 4.108 € 4.903 € 6.842 € 8.211 € 4.108 € 4.903 € 1.250 € 1.500 € Impar 10.914 € 13.096 € 4.903 € 5.896 € 8.211 € 9.853 € 4.903 € 5.896 € 1.500 € 1.800 € Doble página 18.190 € 21.828 € 8.215 € 9.805 € 13.685 € 16.422 € 8.215 € 9.805 € 2.500 € 3.000 € MEDIA PÁGINA Par 5.639 € 6.767 € 2.551 € 3.048 € 4.243 € 5.901 € 2.551 € 3.048 € 675 € 800 € Impar 6.767 € 8.120 € 3.048 € -

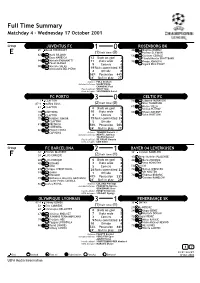

E 1 0 3 0 F 2 1

Full Time Summary Matchday 4 - Wednesday 17 October 2001 Group JUVENTUS FC ROSENBORG BK 25' David TREZEGUET 1046' in Dagfinn ENERLY (1)half time (0) out Hassan EL FAKIRI E in 62' Mark IULIANO in out 59' Christer GEORGE Enzo MARESCA 12 Shots on goal 2 out Harald Martin BRATTBAKK in 84' Michele PARAMATTI 11 Shots wide 4 in out 75' Frode JOHNSEN Pavel NEDVED 9 Corners 6 out Sigurd RUSHFELDT 90' in Marcelo SALAS out Alessandro DEL PIERO 19 Fouls committed 15 4 Offside 0 56% Possession 44% 34' Ball in play 27' Referee: POLL Graham Assistant referees: SHARP Philip CANADINE Paul Fourth official: WILEY Alan UEFA delegate: VERTONGEN Karel FC PORTO30 CELTIC FC 1' CLAYTON 56' in Lubomir MORAVCIK 45'+1 MÁRIO SILVA (2)half time (0) out Alan THOMPSON 61' CLAYTON 67' in Momo SYLLA 8 Shots on goal 0 out Stilian PETROV 10' CÔSTINHA 10 Shots wide 5 88' in Shaun MALONEY 19' CLAYTON 4 Corners 5 out John HARTSON 75' in RUBENS JUNIOR 15 Fouls committed 24 out CLAYTON 5 Offside 3 81' in FREDRICK 50% Possession 50% out CÔSTINHA 24' Ball in play 23' 86' in PAULO COSTA out CAPUCHO Referee: TEMMINK René H.J. Assistant referees: MEINTS Jantinus TALENS Berend Fourth official: DE GRAAF Hennie UEFA delegate: COX Eddie Group FC BARCELONA BAYER 04 LEVERKUSEN 12' Patrick KLUIVERT 2132' Carsten RAMELOW 38' LUIS ENRIQUE (2)half time (1) F 45' Diego Rodolfo PLACENTE 20' LUIS ENRIQUE 6 Shots on goal 5 46' in Boris ZIVKOVIC out 48' in GERARD 3 Shots wide 6 Jens NOWOTNY out XAVI 5 Corners 4 53' LUCIO 69' Philippe CHRISTANVAL 28 Fouls committed 22 76' in Zoltan SEBESCEN out -

Introduction Conflict Narratives in Sport

Lopez-Gonzalez H, Guerrero-Sole F, Haynes R. Manufacturing conflict narratives in Real Madrid versus Barcelona football matches. International Review for the Sociology of Sport. 2014; 49(6):688-706. DOI 10.1177/1012690212464965 Introduction The clásico is the renowned term used to describe the matches between the Real Madrid CF and the FC Barcelona football teams. Although the origins of the rivalry date back more than 100 years, it is now, due basically to the economic repercussion and global impact of the clubs involved, that the clásico has gained unprecedented media attention. Both teams rank in the top two in total fans worldwide, 57.8m for FC Barcelona and 31.3m for Real Madrid CF (Sport+Markt, 2010), and gross income, 450€m for Real Madrid and 479€m for Barcelona (Deloitte, 2012). The intensity of this media coverage is particularly notable in Spain, where football is the most popular sport, and the rivalry between Barcelona and Real Madrid has evolved into a cornerstone of the news agenda (González Ramallal, 2004; Isasi Varela, 2006). However, apart from the emotion and uncertainty derived from their games – with anything between two and five matches a year – the attraction of the Real Madrid-Barcelona (RMD-FCB) rivalry lies beyond the realm of the mere sporting competition and is based upon the mediated discourse around it, fuelled by a 24/7 news cycle. The news pieces do not stand alone but are contained in larger narratives, whose purpose when it comes to sports journalism is not to give a conciliatory account of the events but to ‘emphasize the elements of crisis and contradiction’ (Moragas, 1992:15) and the ‘production of difference’ (Rowe, 2003:282). -

12 National Teams Will Participate in the Tournament, Represent

FAQs Participating Teams and Players How many teams will participate? 12 national teams will participate in the tournament, representing many of the biggest football nations on the planet to create a truly global competitive international tournament. How many players will be in each squad? Each Star Sixes squad will comprise ten players, six will be permitted to play at any one time with the other four being substitutes. When will the teams be confirmed and announced? The 12 countries have been confirmed - Brazil, China, Denmark, England, France, Germany, Italy, Mexico, Nigeria, Portugal, Scotland and Spain. Who will manage the teams? Each Star Sixes team will have an appointed captain who will play and also manage the side. How are players chosen? The selection process is managed by the team captains and Star Sixes. When will players be announced? A galaxy of stars has already been announced, including: Roberto Carlos (Brazil), Steven Gerrard, Michael Owen, David James, Emile Heskey (England), Carles Puyol, Gaizka Mendieta (Spain), Michael Ballack (Germany), Deco (Portugal), Robert Pires (France), Jay-Jay Okocha (Nigeria) and Dominic Matteo (Scotland). Keep an eye on the Star Sixes website and social media for further player announcements in the coming weeks. What kit will the players wear? Players will wear national team colours, designed specifically for the Star Sixes tournament. Keep an eye on the Star Sixes website and social media to find out when the team kits will be revealed. Competition Format, Schedule and Rules What is the competition format? How do teams progress to the final? There will be three groups of four teams.