Internal Parasites in Swine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baylisascariasis

Baylisascariasis Importance Baylisascaris procyonis, an intestinal nematode of raccoons, can cause severe neurological and ocular signs when its larvae migrate in humans, other mammals and birds. Although clinical cases seem to be rare in people, most reported cases have been Last Updated: December 2013 serious and difficult to treat. Severe disease has also been reported in other mammals and birds. Other species of Baylisascaris, particularly B. melis of European badgers and B. columnaris of skunks, can also cause neural and ocular larva migrans in animals, and are potential human pathogens. Etiology Baylisascariasis is caused by intestinal nematodes (family Ascarididae) in the genus Baylisascaris. The three most pathogenic species are Baylisascaris procyonis, B. melis and B. columnaris. The larvae of these three species can cause extensive damage in intermediate/paratenic hosts: they migrate extensively, continue to grow considerably within these hosts, and sometimes invade the CNS or the eye. Their larvae are very similar in appearance, which can make it very difficult to identify the causative agent in some clinical cases. Other species of Baylisascaris including B. transfuga, B. devos, B. schroeder and B. tasmaniensis may also cause larva migrans. In general, the latter organisms are smaller and tend to invade the muscles, intestines and mesentery; however, B. transfuga has been shown to cause ocular and neural larva migrans in some animals. Species Affected Raccoons (Procyon lotor) are usually the definitive hosts for B. procyonis. Other species known to serve as definitive hosts include dogs (which can be both definitive and intermediate hosts) and kinkajous. Coatimundis and ringtails, which are closely related to kinkajous, might also be able to harbor B. -

Top Papers in Neglected Tropical Diseases Diagnosis

Top papers in Neglected Tropical Diseases Diagnosis Professor Peter L Chiodini ESCMID eLibrary © by author Neglected tropical diseases http://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/diseases/en/ Accessed 9th April 2017 • Buruli ulcer • Lymphatic filariasis • Chagas disease • Mycetoma • Dengue and Chikungunya • Onchocerciasis • Dracunculiasis • Rabies • Echinococcosis • Schistosomiasis • Foodborne • Soil-transmitted trematodiases helminthiases • Human African • Taeniasis/Cysticercosis trypanosomiasis • Trachoma • Leishmaniasis • Yaws • ESCMIDLeprosy eLibrary © by author PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases http://journals.plos.org/plosntds/s/journal-information#loc-scope Accessed 9th April 2017 The “big three” diseases, HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis, are not generally considered for PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. Plasmodium vivax possibly ESCMID eLibrary © by author Flynn, FV (1985) “As is your pathology, so is your practice” ESCMID eLibrary © by author Time for a Model List of Essential Diagnostics Schroeder LF et al. NEJM 2016; 374: 2511 ESCMID eLibrary © by author Peruvian Leishmania: braziliensis or mexicana? ESCMID eLibrary © by author Leishmania (Viannia) from Peru ESCMID eLibrary © by author Karimkhani C et al. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16: 584-591 • Global Burden of Disease Study “Unlike the incidence of most other neglected tropical diseases, the incidence of cutaneous leishmaniasis is increasing” ESCMID eLibrary © by author Karimkhani C et al. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16: 584-591 ESCMID eLibrary © by author Akhoundi M et al. Molecular Aspects of Medicine (2017) doi: 10.1016/ j.mam.2016.11.012. ESCMID eLibrary © by author Akhoundi M et al. Molecular Aspects of Medicine (2017) doi: 10.1016/ j.mam.2016.11.012. ESCMID eLibrary © by author Akhoundi M et al. Molecular Aspects of Medicine (2017) doi: 10.1016/ j.mam.2016.11.012. -

An Update on the Use of Helminths to Treat Crohn's and Other

Parasitol Res (2009) 104:217–221 DOI 10.1007/s00436-008-1297-5 REVIEW An update on the use of helminths to treat Crohn’s and other autoimmunune diseases Aditya Reddy & Bernard Fried Received: 17 August 2008 /Accepted: 20 November 2008 /Published online: 3 December 2008 # Springer-Verlag 2008 Abstract This review updates our previous one (Reddy immune status of acutely and chronically helminth-infected and Fried, Parasitol Research 100: 921–927, 2007)on humans. Although two species of hookworms, Ancylostoma Crohn’s disease and helminths. The review considers the duodenale and N. americanus, commonly infect humans most recent literature on Trichuris suis therapy and Crohn’s through contact with contaminated soil (Hotez et al. 2004), and the significant literature on the use of Necator we have not seen papers on therapeutic interventions with americanus larvae to treat Crohn’s and other autoimmune A. duodenale. Therapy with N. americanus larvae is easier disorders. The pros and cons of helminth therapy as related to use by physicians than the Trichuris suis ova (TSO) to autoimmune disorders are discussed in the review. We also treatment because of the fewer number of treatments and discuss the relationship of the bacterium Campylobacter more long lasting effects of the hookworm treatments. jejuni and T. suis in Crohn’s disease. The significant Though we will continue to use the term TSO in our literature on helminths other than N. americanus and T. review, the term should really be TSE, because the suis as related to autoimmune diseases is also reviewed. treatment is with Trichuris eggs not ova. -

Hybrid Ascaris Suum/Lumbricoides (Ascarididae) Infestation in a Pig

Cent Eur J Public Health 2013; 21 (4): 224–226 HYBRID ASCARIS SUUM/LUMBRICOIDES (ASCARIDIDAE) INFESTATION IN A PIG FARMER: A RARE CASE OF ZOONOTIC ASCARIASIS Moreno Dutto1, Nicola Petrosillo2 1Department of Prevention, Local Health Unit, ASL CN1, Saluzzo (CN), Italy 2National Institute for Infectious Diseases “Lazzaro Spallanzani”, Rome, Italy SUMMARY We present a case of the 42 year old pig farmer from the province of Cuneo in Northwest Italy who was infected by the soil-transmitted nema- tode Ascaris sp. In November 2010 the patient found one worm in his stool, subsequently identified as female specimen of Ascaris sp. After a first anthelmintic treatment, another worm was found in his stool, that was later identified as male Ascaris sp. Blood tests prescribed by the patient’s family physician, as suggested by a parasitologist, found nothing abnormal. A chest x-ray was negative for Loeffler’s syndrome and an ultrasound of the abdomen was normal with no evidence of hepatic problems. The nematode collected from the patient was genetically characterized using the ribosomal nuclear marker ITS. The PCR-RFLP analysis showed a hybrid genotype, intermediate between A. suum/lumbricoides. It was subsequently ascertained that some pigs on the patient’s farm had A. suum infection; no other family member was infected. A cross- infestation from the pigs as source was the likely way of transmission. This conclusion is further warranted by the fact, that the patient is a confirmed nail-biter, a habit which facilitates oral-fecal transmission of parasites and pathogens. Key words: ascariasis, Ascaris suum, cross infection, pigs, zoonosis, hybrid genotype Address for correspondence: M. -

High Heritability for Ascaris and Trichuris Infection Levels in Pigs

Heredity (2009) 102, 357–364 & 2009 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0018-067X/09 $32.00 www.nature.com/hdy ORIGINAL ARTICLE High heritability for Ascaris and Trichuris infection levels in pigs P Nejsum1,2, A Roepstorff1,CBJrgensen2, M Fredholm2, HHH Go¨ring3, TJC Anderson3 and SM Thamsborg1 1Danish Centre for Experimental Parasitology, Department of Veterinary Pathobiology, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark; 2Genetics and Bioinformatics, Department of Animal and Veterinary Basic Sciences, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark and 3Department of Genetics, Southwest Foundation for Biomedical Research, San Antonio, TX, USA Aggregated distributions of macroparasites within their host 0.32–0.73 of the phenotypic variation for T. suis could be populations are characteristic of most natural and experi- attributed to genetic factors. For A. suum, heritabilities of mental infections. We designed this study to measure the 0.29–0.31 were estimated for log (FEC þ 1) at weeks 7–14 amount of variation that is attributable to host genetic factors p.i., whereas the heritability of log worm counts was 0.45. in a pig–helminth system. In total, 195 piglets were produced Strong positive genetic correlations (0.75–0.89) between after artificial insemination of 19 sows (Danish Landrace– T. suis and A. suum FECs suggest that resistance to both Yorkshire crossbreds) with semen selected from 13 indivi- infections involves regulation by overlapping genes. Our data dual Duroc boars (1 or 2 sows per boar; mean litter size: demonstrate that there is a strong genetic component in 10.3; 5–14 piglets per litter). -

An Overview of Anthelmintic Drugs in Ascaris Suum Intestine

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Creative Components Dissertations Spring 2019 An Overview of Anthelmintic Drugs in Ascaris suum Intestine Katie Tharaldson Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/creativecomponents Part of the Chemicals and Drugs Commons Recommended Citation Tharaldson, Katie, "An Overview of Anthelmintic Drugs in Ascaris suum Intestine" (2019). Creative Components. 262. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/creativecomponents/262 This Creative Component is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Creative Components by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tharaldson Overview of anthelmintic drugs and their receptors Part 1 Abstract In part 1 of this paper, I will discuss Ascaris suum and Ascaris lumbricoides. Ascaris suum acts as a model organism for Ascaris lumbricoides, a parasitic nematode that impacts roughly 1.2 billion people worldwide (de Silva et al. 2003). I will then go into the anthelmintic drugs currently being used to treat these infection, as well as the receptors they act on. In part 2 of this paper, I will discuss the research I did with levamisole, an anthelmintic drug, on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) in the intestine of Ascaris suum. There were 5 control worms, as well as 5 levamisole treated worms. In the past, the nAChRs have been studied predominantly on the muscle in all nematode species. However, in previous work in the lab, although unpublished, there was promising expression of nAChRs in Ascaris suum intestine. -

The Transcriptome of Trichuris Suis – First Molecular Insights Into a Parasite with Curative Properties for Key Immune Diseases of Humans

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchOnline at James Cook University The Transcriptome of Trichuris suis – First Molecular Insights into a Parasite with Curative Properties for Key Immune Diseases of Humans Cinzia Cantacessi1*, Neil D. Young1, Peter Nejsum2, Aaron R. Jex1, Bronwyn E. Campbell1, Ross S. Hall1, Stig M. Thamsborg2, Jean-Pierre Scheerlinck1,3, Robin B. Gasser1* 1 Department of Veterinary Science, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria, Australia, 2 Departments of Veterinary Disease Biology and Basic Animal and Veterinary Science, University of Copenhagen, Frederiksberg, Denmark, 3 Centre for Animal Biotechnology, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Australia Abstract Background: Iatrogenic infection of humans with Trichuris suis (a parasitic nematode of swine) is being evaluated or promoted as a biological, curative treatment of immune diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and ulcerative colitis, in humans. Although it is understood that short-term T. suis infectioninpeoplewithsuchdiseases usually induces a modified Th2-immune response, nothing is known about the molecules in the parasite that induce this response. Methodology/Principal Findings: As a first step toward filling the gaps in our knowledge of the molecular biology of T. suis, we characterised the transcriptome of the adult stage of this nematode employing next-generation sequencing and bioinformatic techniques. A total of ,65,000,000 reads were generated and assembled into -

The Worm Returns Joel V

COMMENT HISTORY Centenary of the CONSERVATION Suburbanites’ BIOLOGY How life OBITUARY Keith Campbell, equation that launched conflicted relationship with turns random energy creator of Dolly the sheep, crystallography p.186 wild animals p.188 into useful work p.191 remembered p.193 JOEL WEINSTOCK LAB JOEL WEINSTOCK The whipworm Trichuris suis is currently in trials for treating Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. The worm returns Joel V. Weinstock explains why several clinical trials are deliberately infecting people with helminths to treat autoimmune diseases. or as long as modern humans have a rapid increase in an entirely new set of to wait until the airport could get up and existed, they have carried parasitic diseases, such as inflammatory bowel running again. worms. That is around 200,000 years. disease (the focus of my research). These I was writing a review article at the time, FLike many bacteria, some roundworms and once-rare diseases, caused by autoimmun- on inflammatory bowel disease, and edit- flatworms (helminths) reside harmlessly in ity, have become relatively common in less ing a book about parasites. That day, I was the gut. Others can cause problems. than a century. Why? focusing on a chapter about how the ‘evil’ Before antibiotics and improvements This question was plaguing me as I properties of intestinal parasites are often in sanitation, gastrointestinal infections sat in a plane on the runway of Chicago’s overblown. Considering the vast number of — mostly with bacteria — killed perhaps O’Hare airport for five hours one day dur- people who have carried them throughout one in five children and many adults. -

Infectious Organisms of Ophthalmic Importance

INFECTIOUS ORGANISMS OF OPHTHALMIC IMPORTANCE Diane VH Hendrix, DVM, DACVO University of Tennessee, College of Veterinary Medicine, Knoxville, TN 37996 OCULAR BACTERIOLOGY Bacteria are prokaryotic organisms consisting of a cell membrane, cytoplasm, RNA, DNA, often a cell wall, and sometimes specialized surface structures such as capsules or pili. Bacteria lack a nuclear membrane and mitotic apparatus. The DNA of most bacteria is organized into a single circular chromosome. Additionally, the bacterial cytoplasm may contain smaller molecules of DNA– plasmids –that carry information for drug resistance or code for toxins that can affect host cellular functions. Some physical characteristics of bacteria are variable. Mycoplasma lack a rigid cell wall, and some agents such as Borrelia and Leptospira have flexible, thin walls. Pili are short, hair-like extensions at the cell membrane of some bacteria that mediate adhesion to specific surfaces. While fimbriae or pili aid in initial colonization of the host, they may also increase susceptibility of bacteria to phagocytosis. Bacteria reproduce by asexual binary fission. The bacterial growth cycle in a rate-limiting, closed environment or culture typically consists of four phases: lag phase, logarithmic growth phase, stationary growth phase, and decline phase. Iron is essential; its availability affects bacterial growth and can influence the nature of a bacterial infection. The fact that the eye is iron-deficient may aid in its resistance to bacteria. Bacteria that are considered to be nonpathogenic or weakly pathogenic can cause infection in compromised hosts or present as co-infections. Some examples of opportunistic bacteria include Staphylococcus epidermidis, Bacillus spp., Corynebacterium spp., Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp., Enterobacter spp., Serratia spp., and Pseudomonas spp. -

Parasites 1: Trematodes and Cestodes

Learning Objectives • Be familiar with general prevalence of nematodes and life stages • Know most important soil-borne transmitted nematodes • Know basic attributes of intestinal nematodes and be able to distinguish these nematodes from each other and also from other Lecture 4: Emerging Parasitic types of nematodes • Understand life cycles of nematodes, noting similarities and significant differences Helminths part 2: Intestinal • Know infective stages, various hosts involved in a particular cycle • Be familiar with diagnostic criteria, epidemiology, pathogenicity, Nematodes &treatment • Identify locations in world where certain parasites exist Presented by Matt Tucker, M.S, MSPH • Note common drugs that are used to treat parasites • Describe factors of intestinal nematodes that can make them emerging [email protected] infectious diseases HSC4933 Emerging Infectious Diseases HSC4933. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2 Readings-Nematodes Monsters Inside Me • Ch. 11 (pp. 288-289, 289-90, 295 • Just for fun: • Baylisascariasis (Baylisascaris procyonis, raccoon zoonosis): Background: http://animal.discovery.com/invertebrates/monsters-inside-me/baylisascaris- [box 11.1], 298-99, 299-301, 304 raccoon-roundworm/ Video: http://animal.discovery.com/videos/monsters-inside-me-the-baylisascaris- [box 11.2]) parasite.html Strongyloidiasis (Strongyloides stercoralis, the threadworm): Background: http://animal.discovery.com/invertebrates/monsters-inside-me/strongyloides- • Ch. 14 (p. 365, 367 [table 14.1]) stercoralis-threadworm/ Videos: http://animal.discovery.com/videos/monsters-inside-me-the-threadworm.html http://animal.discovery.com/videos/monsters-inside-me-strongyloides-threadworm.html Angiostrongyliasis (Angiostrongylus cantonensis, the rat lungworm): Background: http://animal.discovery.com/invertebrates/monsters-inside- me/angiostrongyliasis-rat-lungworm/ Video: http://animal.discovery.com/videos/monsters-inside-me-the-rat-lungworm.html HSC4933. -

Helminth Therapy Or Elimination: Epidemiological, Immunological, and Clinical Considerations

Review Helminth therapy or elimination: epidemiological, immunological, and clinical considerations Linda J Wammes, Harriet Mpairwe, Alison M Elliott, Maria Yazdanbakhsh Lancet Infect Dis 2014; Deworming is rightly advocated to prevent helminth-induced morbidity. Nevertheless, in affl uent countries, the 14: 1150–62 deliberate infection of patients with worms is being explored as a possible treatment for infl ammatory diseases. Several Published Online clinical trials are currently registered, for example, to assess the safety or effi cacy of Trichuris suis ova in allergies, June 27, 2014 infl ammatory bowel diseases, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and autism, and the Necator americanus http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ S1473-3099(14)70771-6 larvae for allergic rhinitis, asthma, coeliac disease, and multiple sclerosis. Studies in animals provide strong evidence Department of Parasitology, that helminths can not only downregulate parasite-specifi c immune responses, but also modulate autoimmune and Leiden University Medical allergic infl ammatory responses and improve metabolic homoeostasis. This fi nding suggests that deworming could Center, Leiden, Netherlands lead to the emergence of infl ammatory and metabolic conditions in countries that are not prepared for these new (L J Wammes MD, epidemics. Further studies in endemic countries are needed to assess this risk and to enhance understanding of how Prof M Yazdanbakhsh PhD); MRC/Uganda Virus Research helminths modulate infl ammatory and metabolic pathways. Studies are similarly needed in non-endemic countries to Institute, Uganda Research move helminth-related interventions that show promise in animals, and in phase 1 and 2 studies in human beings, into Unit on AIDS, Entebbe, Uganda the therapeutic development pipeline. -

Diagnostic Notes

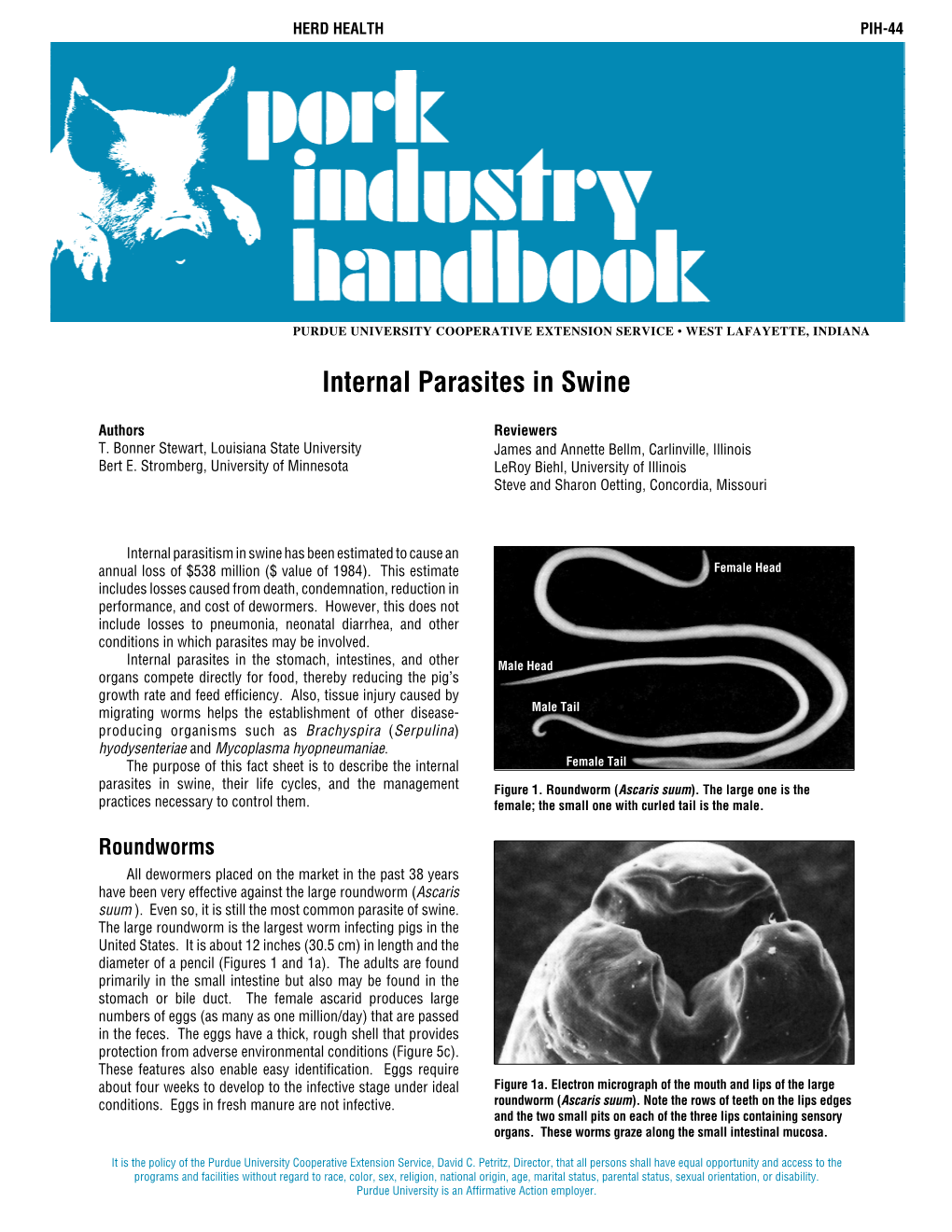

DIAGNOSTIC NOTES Pig parasite diagnosis Robert M. Corwin, DVM, PhD arasites in swine have an impact on performance, with effects and the persistence or life span of the parasite. ranging from impaired growth and wasteful feed consumption Postmortem examination should reveal adult worms in their principal to clinical disease, debilitation, and perhaps even death. It is sites of infection, e.g., ascarids in the small intestine. Lesions associ- particularly important to diagnose subclinical parasitism, which can ated with larval infection, such as nodules of Oesophagostomum in have serious economic consequences and which should be treated the colon may not have larvae present or apparent. Lungworms also with ongoing preventive measures. have rather specific sites at least in young worm populations, viz., the Internal parasitism is caused by nematode roundworms and coccidia bronchioles of the diaphragmatic lobes of the lungs. in the gastrointestinal tract, lungworms in the respiratory tract, and by All of these parasites are directly transmissible from the environment ectoparasites. The most commonly encountered gastrointestinal para- with ingestion of eggs or larvae. Strongyloides may also be passed in sites are the large roundworm Ascaris suum, the threadworm Stron- the colostrum or penetrate skin, and transmission of the lung worm gyloides ransomi, the whipworm Trichuris suis, the nodular worm and the kidney worm may involve earthworms. Oesophagostomum dentatum, and the coccidia, especially lsospora suis and Cryptosporidium parvum in neonates and Eimeria spp at Ascaris suum --”large roundworm” weaning. (Figure 1A) Diagnosis of internal parasites is best accomplished by fecal examina- egg: 45-60 µm, yellowish brown, spherical, mammillated (Figure 1B) tion using a flotation technique and/or by necropsy.