4FRI Rim Country Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lower Gila Region, Arizona

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR HUBERT WORK, Secretary UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, Director Water-Supply Paper 498 THE LOWER GILA REGION, ARIZONA A GEOGBAPHIC, GEOLOGIC, AND HTDBOLOGIC BECONNAISSANCE WITH A GUIDE TO DESEET WATEEING PIACES BY CLYDE P. ROSS WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1923 ADDITIONAL COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION MAT BE PROCURED FROM THE SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUMENTS GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON, D. C. AT 50 CENTS PEE COPY PURCHASER AGREES NOT TO RESELL OR DISTRIBUTE THIS COPT FOR PROFIT. PUB. RES. 57, APPROVED MAT 11, 1822 CONTENTS. I Page. Preface, by O. E. Melnzer_____________ __ xr Introduction_ _ ___ __ _ 1 Location and extent of the region_____._________ _ J. Scope of the report- 1 Plan _________________________________ 1 General chapters _ __ ___ _ '. , 1 ' Route'descriptions and logs ___ __ _ 2 Chapter on watering places _ , 3 Maps_____________,_______,_______._____ 3 Acknowledgments ______________'- __________,______ 4 General features of the region___ _ ______ _ ., _ _ 4 Climate__,_______________________________ 4 History _____'_____________________________,_ 7 Industrial development___ ____ _ _ _ __ _ 12 Mining __________________________________ 12 Agriculture__-_______'.____________________ 13 Stock raising __ 15 Flora _____________________________________ 15 Fauna _________________________ ,_________ 16 Topography . _ ___ _, 17 Geology_____________ _ _ '. ___ 19 Bock formations. _ _ '. __ '_ ----,----- 20 Basal complex___________, _____ 1 L __. 20 Tertiary lavas ___________________ _____ 21 Tertiary sedimentary formations___T_____1___,r 23 Quaternary sedimentary formations _'__ _ r- 24 > Quaternary basalt ______________._________ 27 Structure _______________________ ______ 27 Geologic history _____ _____________ _ _____ 28 Early pre-Cambrian time______________________ . -

Phase I Environmental Assessment, East Clear Creek, Coconino County

PHASE 1 ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT EAST CLEAR CREEK, COCONINO COUNTY, ARIZONA Resolution Copper Prepared for: Attn: Mary Morissette 102 Magma Heights Superior, Arizona 85173-2523 Project Number: 807.211 September 4, 2020 Date WestLand Resources, Inc. 4001 E. Paradise Falls Drive Tucson, Arizona 85712 5202069585 East Clear Creek, Coconino County, Arizona Phase 1 Environmental Assessment TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY....................................................................................................................... ES-1 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Purpose ............................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2. Scope of Services .............................................................................................................................. 2 1.3. Limitations and Exceptions ............................................................................................................ 2 1.4. Special Terms and Conditions ........................................................................................................ 3 1.5. User Reliance ..................................................................................................................................... 3 1.6. Continued Viability .......................................................................................................................... -

Water and Riparian Resource Report

Four Forest Restoration Initiative, Rim Country EIS DRAFT Water and Riparian Resource Report Prepared by: Paul Brown Watershed Program Manager, ASNF for: 4FRI Rim Country EIS Date 5/16/2019 In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992. -

5-Yr Review LEVI

Little Colorado Spinedace (Lepidomeda vittata) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation Photo by Arizona Game and Fish Department U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Arizona Ecological Services Office Phoenix, Arizona 5-YEAR REVIEW Little Colorado Spinedace/Lepidomeda vittata 1.0 GENERAL INFORMATION 1.1 Reviewers Lead Regional Office: Southwest (Region 2), Wendy Brown, Endangered Species Recovery Coordinator, (505) 248-6664; Brady McGee, Endangered Species Recovery Biologist, (505) 248-6657. Lead Field Office: Arizona Ecological Services Office, Shaula Hedwall, Senior Fish and Wildlife Biologist, (928) 226-0614 x103; Steven L. Spangle, Field Supervisor, (602) 242-0210 x244. Cooperating Field Office: Arizona Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office, Stewart Jacks, Project Leader, (928) 338-4288 x20. 1.2 Methodology used to complete the review: This review was conducted by Arizona Ecological Services Office (AESO) staff using information from species survey and monitoring reports, the 1998 Little Colorado River Spinedace (Lepidomeda vittata) Recovery Plan (Recovery Plan) (USFWS 1998), peer-reviewed journal articles, and documents generated as part of section 7 and section 10 consultations. We discussed potential recommendations to assist in recovery of the species with recognized spinedace experts. 1.3 Background: 1.3.1 FR Notice citation announcing initiation of this review: The FR notice initiating this review was published on January 11, 2006 (71 FR 1765). This notice opened a 90-day request for information period, which closed on April 11, 2006. We received comments from the Arizona Game and Fish Department (AGFD) and from Mr. Jim Crosswhite, owner of the EC Bar Ranch on Nutrioso Creek. 1 1.3.2 Listing history Original Listing FR notice: 32 FR 2001 (USFWS 1967) Date listed: March 11, 1967 Entity listed: Species, Lepidomeda vittata Classification: Threatened. -

Roundtail Chub Repatriated to the Blue River

Volume 1 | Issue 2 | Summer 2015 Roundtail Chub Repatriated to the Blue River Inside this issue: With a fish exclusion barrier in place and a marked decline of catfish, the time was #TRENDINGNOW ................. 2 right for stocking Roundtail Chub into a remote eastern Arizona stream. New Initiative Launched for Southwest Native Trout.......... 2 On April 30, 2015, the Reclamation, and Marsh and Blue River. A total of 222 AZ 6-Species Conservation Department stocked 876 Associates LLC embarked on a Roundtail Chub were Agreement Renewal .............. 2 juvenile Roundtail Chub from mission to find, collect and stocked into the Blue River. IN THE FIELD ........................ 3 ARCC into the Blue River near bring into captivity some During annual monitoring, Recent and Upcoming AZGFD- the Juan Miller Crossing. Roundtail Chub for captive led Activities ........................... 3 five months later, Additional augmentation propagation from the nearest- Department staff captured Spikedace Stocked into Spring stockings to enhance the genetic neighbor population in Eagle Creek ..................................... 3 42 of the stocked chub, representation of the Blue River Creek. The Aquatic Research some of which had travelled BACK AT THE PONDS .......... 4 Roundtail Chub will be and Conservation Center as far as seven miles Native Fish Identification performed later this year. (ARCC) held and raised the upstream from the stocking Workshop at ARCC................ 4 offspring of those chub for Stockings will continue for the location. future stocking into the Blue next several years until that River. population is established in the Department biologists conducted annual Blue River and genetically In 2012, the partners delivered monitoring in subsequent mimics the wild source captive-raised juvenile years, capturing three chub population. -

Oak Flat Acres – 2,422

Location – Pinal County, east of Superior Oak Flat Acres – 2,422 The Oak Flat parcel and surrounding lands include approximately 2,422 acres of Tonto National Forest lands intermingled with private lands owned by Resolution Copper. Unpatented mining claims staked as early as 1917 cover this suitable nesting place for birds of prey, and bats may inhabit parcel except for 760 acres that were withdrawn from mineral some of the historic mine shafts existing in the area. Protection entry through executive order during the Eisenhower of these important features is part of the planning process for Administration. These 2,422 acres of federal land, which include the Resolution Copper mine. Specific language in the bill calls the withdrawal area, would be traded to Resolution Copper in the for a management plan and significant limitations on surface land exchange for more than 5,000 acres of high-value uses within the easement area. This includes appropriate conservation lands owned by the company in various Arizona levels of non-motorized public access and use and other locations. measures to protect the open space and conservation values of Apache Leap. When the ownership of this parcel transfers to Resolution Copper, access to some Oak Flat recreational sites will be limited or lost. • To protect public safety, rock climbing and bouldering activities This will include 16 campsites that are located on about 50 acres ultimately will need to be relocated. Resolution Copper is of the forest service parcel as well as portions of the parcel that working with interested stakeholders, including members of the are used for climbing and bouldering. -

Appendix / Attachment 1A

ATTACHMENT 1A (Supplemental Documentation to the: Mogollon Rim Water Resource, Management Study Report of Findings) Geology and Structural Controls of Groundwater, Mogollon Rim Water Resources Management Study by Gaeaorama, Inc., July, 2006 GEOLOGY AND STRUCTURAL CONTROLS OF GROUNDWATER, MOGOLLON RIM WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT STUDY Prepared for the Bureau of Reclamation GÆAORAMA, INC. Blanding, Utah DRAFT FOR REVIEW 22 July 2006 CONTENTS page Executive Summary…………………………………………………………………………….. 1 MRWRMS ii 1/18/11 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………... 2 GIS database……………………………………………………………………………………. 5 Faults and fault systems………………………………………………………………………… 6 Proterozoic faults…………………………………………………………………………… 6 Re-activated Proterozoic faults……………………………………………………………... 6 Post-Paleozoic faults of likely Proterozoic inheritance…………………………………….. 7 Tertiary fault systems……………………………………………………………………….. 8 Verde graben system……………………………………………………………………. 8 East- to northeast-trending system……………………………………………………… 9 North-trending system…………………………………………………………………...9 Regional disposition of Paleozoic strata………………………………………………………. 10 Mogollon Rim Formation – distribution and implications……………………………………..10 Relation of springs to faults…………………………………………………………………… 11 Fossil Springs……………………………………………………………………………… 13 Tonto Bridge Spring………………………………………………………………………..14 Webber Spring and Flowing Spring………………………………………………………..15 Cold Spring………………………………………………………………………………... 16 Fossil Canyon-Strawberry-Pine area…………………………………………………………...17 Speculations on aquifer systems………………………………………………………………. -

Native Fish Restoration in Redrock Canyon

U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Final Environmental Assessment Phoenix Area Office NATIVE FISH RESTORATION IN REDROCK CANYON U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Southwestern Region Coronado National Forest Santa Cruz County, Arizona June 2008 Bureau of Reclamation Finding of No Significant Impact U.S. Forest Service Finding of No Significant Impact Decision Notice INTRODUCTION In accordance with the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (Public Law 91-190, as amended), the Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation), as the lead Federal agency, and the Forest Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), and Arizona Game and Fish Department (AGFD), as cooperating agencies, have issued the attached final environmental assessment (EA) to disclose the potential environmental impacts resulting from construction of a fish barrier, removal of nonnative fishes with the piscicide antimycin A and/or rotenone, and restoration of native fishes and amphibians in Redrock Canyon on the Coronado National Forest (CNF). The Proposed Action is intended to improve the recovery status of federally listed fish and amphibians (Gila chub, Gila topminnow, Chiricahua leopard frog, and Sonora tiger salamander) and maintain a healthy native fishery in Redrock Canyon consistent with the CNF Plan and ongoing Endangered Species Act (ESA), Section 7(a)(2), consultation between Reclamation and the FWS. BACKGROUND The Proposed Action is part of a larger program being implemented by Reclamation to construct a series of fish barriers within the Gila River Basin to prevent the invasion of nonnative fishes into high-priority streams occupied by imperiled native fishes. This program is mandated by a FWS biological opinion on impacts of Central Arizona Project (CAP) water transfers to the Gila River Basin (FWS 2008a). -

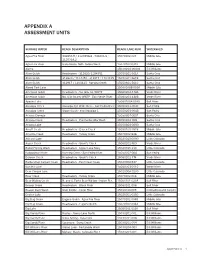

Appendix a Assessment Units

APPENDIX A ASSESSMENT UNITS SURFACE WATER REACH DESCRIPTION REACH/LAKE NUM WATERSHED Agua Fria River 341853.9 / 1120358.6 - 341804.8 / 15070102-023 Middle Gila 1120319.2 Agua Fria River State Route 169 - Yarber Wash 15070102-031B Middle Gila Alamo 15030204-0040A Bill Williams Alum Gulch Headwaters - 312820/1104351 15050301-561A Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312820 / 1104351 - 312917 / 1104425 15050301-561B Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312917 / 1104425 - Sonoita Creek 15050301-561C Santa Cruz Alvord Park Lake 15060106B-0050 Middle Gila American Gulch Headwaters - No. Gila Co. WWTP 15060203-448A Verde River American Gulch No. Gila County WWTP - East Verde River 15060203-448B Verde River Apache Lake 15060106A-0070 Salt River Aravaipa Creek Aravaipa Cyn Wilderness - San Pedro River 15050203-004C San Pedro Aravaipa Creek Stowe Gulch - end Aravaipa C 15050203-004B San Pedro Arivaca Cienega 15050304-0001 Santa Cruz Arivaca Creek Headwaters - Puertocito/Alta Wash 15050304-008 Santa Cruz Arivaca Lake 15050304-0080 Santa Cruz Arnett Creek Headwaters - Queen Creek 15050100-1818 Middle Gila Arrastra Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-848 Middle Gila Ashurst Lake 15020015-0090 Little Colorado Aspen Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-769 Verde River Babbit Spring Wash Headwaters - Upper Lake Mary 15020015-210 Little Colorado Babocomari River Banning Creek - San Pedro River 15050202-004 San Pedro Bannon Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-774 Verde River Barbershop Canyon Creek Headwaters - East Clear Creek 15020008-537 Little Colorado Bartlett Lake 15060203-0110 Verde River Bear Canyon Lake 15020008-0130 Little Colorado Bear Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-046 Middle Gila Bear Wallow Creek N. and S. Forks Bear Wallow - Indian Res. -

Gerald J. Gottfried and Daniel G. Nearyl

Hydrology of the Upper Parker Creek Watershed, Sierra Ancha Mountains, Arizona Item Type text; Proceedings Authors Gottfried, Gerald J.; Neary, Daniel G. Publisher Arizona-Nevada Academy of Science Journal Hydrology and Water Resources in Arizona and the Southwest Rights Copyright ©, where appropriate, is held by the author. Download date 02/10/2021 12:18:47 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/296587 HYDROLOGY OF THE UPPER PARKER CREEK WATERSHED, SIERRA ANCHA MOUNTAINS, ARIZONA Gerald J. Gottfried and Daniel G. Nearyl The hydrology of headwater watersheds and river Creek watershed, and reevaluates the hypothesis basins is variable because of fluctuations in climate that Upper Parker Creek could serve as the hydro- and in watershed conditions due to natural or logic control for post -fire streamflow evaluations human influences. The climate in the southwestern being conducted on the nearby Middle Fork of United States is variable, with cycles of extendedWorkman Creek, which burned in 2000. The pres- periods of drought or of abundant moisture. These ent knowledge of wildfire effects on hydrologic cycles have been documented for hundreds of responses is low, and data from Upper Parker years in the tree rings of the Southwest (Swetnam Creek and Workman Creek should help alleviate and Betancourt 1998). Hydrologic records that the gap. The relationships for annual and seasonal only span a decade or so may not provide a true runoff volumes are of particular interest in the indication of watershed responses because the present evaluation; subsequent analyses will eval- measurements could be from a period of extreme uate relationships for peak flows. -

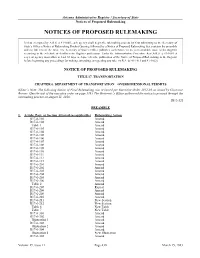

Notices of Proposed Rulemaking NOTICES of PROPOSED RULEMAKING

Arizona Administrative Register / Secretary of State Notices of Proposed Rulemaking NOTICES OF PROPOSED RULEMAKING Unless exempted by A.R.S. § 41-1005, each agency shall begin the rulemaking process by first submitting to the Secretary of State’s Office a Notice of Rulemaking Docket Opening followed by a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking that contains the preamble and the full text of the rules. The Secretary of State’s Office publishes each Notice in the next available issue of the Register according to the schedule of deadlines for Register publication. Under the Administrative Procedure Act (A.R.S. § 41-1001 et seq.), an agency must allow at least 30 days to elapse after the publication of the Notice of Proposed Rulemaking in the Register before beginning any proceedings for making, amending, or repealing any rule. (A.R.S. §§ 41-1013 and 41-1022) NOTICE OF PROPOSED RULEMAKING TITLE 17. TRANSPORTATION CHAPTER 6. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION – OVERDIMENSIONAL PERMITS Editor’s Note: The following Notice of Final Rulemaking was reviewed per Executive Order 2012-03 as issued by Governor Brewer. (See the text of the executive order on page 526.) The Governor’s Office authorized the notice to proceed through the rulemaking process on August 11, 2010. [R13-32] PREAMBLE 1. Article, Part, or Section Affected (as applicable) Rulemaking Action R17-6-101 Amend R17-6-102 Amend Table 1 Amend R17-6-103 Amend R17-6-104 Amend R17-6-105 Amend R17-6-106 Amend R17-6-107 Amend R17-6-108 Amend R17-6-109 Amend R17-6-110 Amend R17-6-111 Amend R17-6-112 Amend R17-6-113 -

Tonto National Forest 2019 LRMP Biological Opinion

United States Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Arizona Ecological Services Office 9828 North 31st Avenue #C3 Phoenix, Arizona 85051-2517 Telephone: (602) 242-0210 Fax: (602) 242-2513 In reply, refer to: AESO/SE 02E00000-2012-F-0011-R001/02EAAZ00-2020-F-0206 December 17, 2019 Mr. Neil Bosworth, Forest Supervisor Tonto National Forest Supervisor’s Office 2324 East McDowell Road Phoenix, Arizona 85006 RE: Continued Implementation of the Tonto National Forest’s Land and Resource Management Plan (LRMP) for the Mexican Spotted Owl and its Designated Critical Habitat Dear Mr. Bosworth: This document transmits our biological opinion (BO) for the reinitiation of formal consultation pursuant to section 7 of the Endangered Species Act of 1973 (16 U.S.C. § 1531-1544), as amended (ESA or Act), for the Tonto National Forest’s (NF) Land and Resource Management Plan (LRMP). The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) and Forest Service are conducting this reinitiation in response to a September 12, 2019, court order in WildEarth Guardians v. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 4:13-CV-00151-RCC. In response to this court order, as well as updated information regarding subjects in the BO, and current regulation and policy, we are updating the Status of the Species, Environmental Baseline, Effects of the Action, Cumulative Effects, and Incidental Take Statement sections of the April 30, 2012, Tonto NF LRMP BO (02E00000-2012-F-0011). We received your updated Biological Assessment (BA) on November 23, 2019. We are consulting on effects to the threatened Mexican spotted owl (Strix occidentalis lucida) (spotted owl or owl) and its critical habitat from the Forest Services’ continued implementation of the Tonto NF’s LRMP.