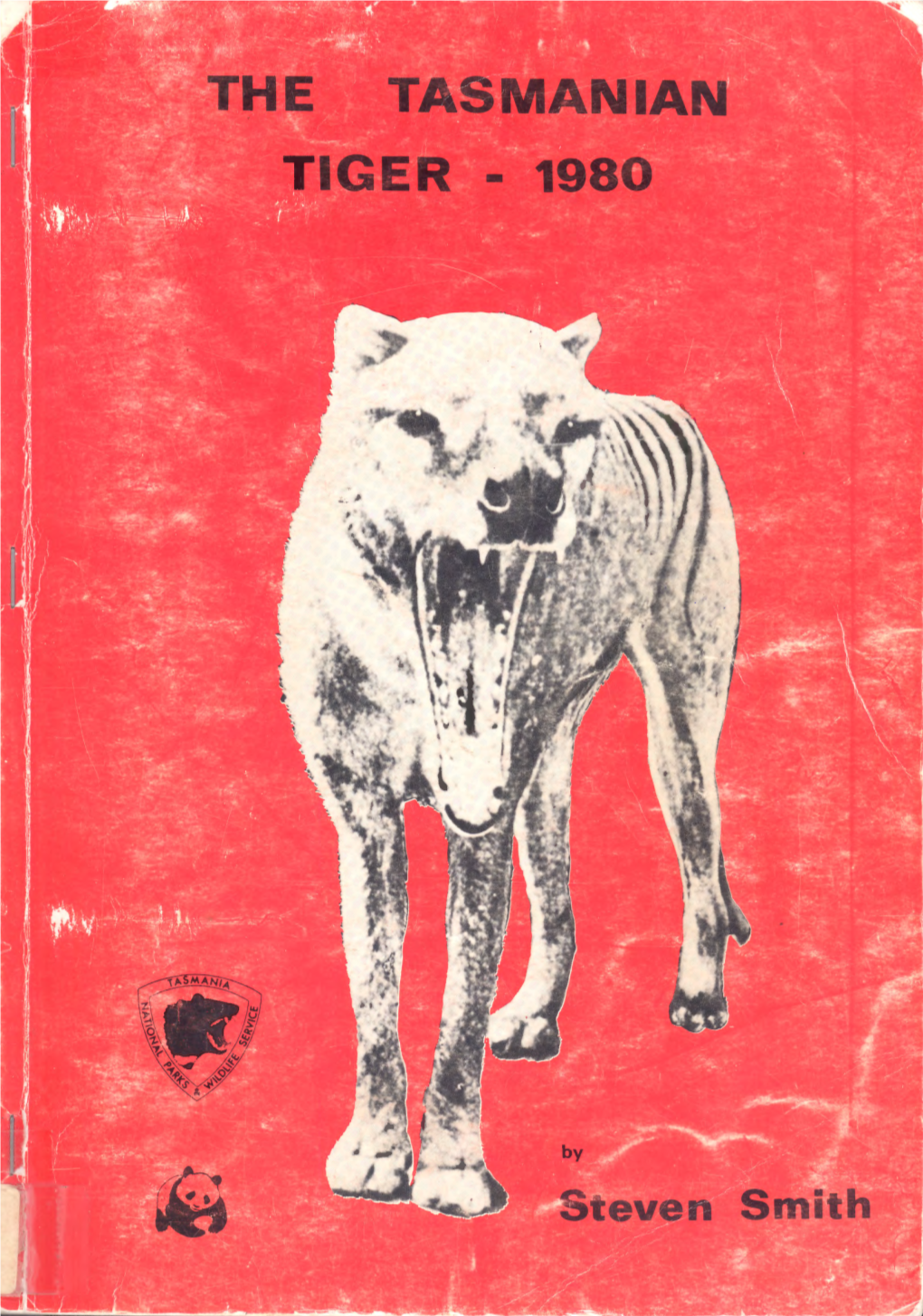

Steven J. Smith National Parks and Wild! Ife Service, Tasmania May 1981

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Folklore & History of the Heritage Highway

Folklore & History of the Heritage Highway Keep an eye out between Tunbridge and Kemton for sixteen silhouettes. Some are quite close to road, some are high on the hilltops. What stories can they tell us about the history of this intriguing region. Page 2 Two hundred years on there’s still plenty of ways to get held up on the Heritage Highway The Silhouette sculpture trail along the Southern half of the Midland Highway is completed, nine years after it was started by locals Folko Kooper and Maureen Craig. The trail between Tunbridge and Kempton, has become an enjoyable feature of the journey along the highway. Installation of four coaching-related sculptures at Kempton earlier this year marked completion of a trail which now has 16 pieces. Page 3 Leaving Oatlands towards the North, on the right side of the Heritage Highway. Troop Of Soldiers—St Peters Pass Van Diemen’s Land was first and foremost a British military outpost. Soldiers accompanied the convicts on the transport ships, supervised the rationing of supplies, and guarded the chain gangs, They also supervised construction of bridges public and private buildings– as well as watching out for the French! Most didn’t stay long. There were other British interests around the world to defend. Many of the convicts they guarded had also been soldiers, but were reduced to committing crime once the wars they were fighting ended and they were out of a job. Chain Gang—North off York Plains Turn-off There was a lot to do to build the colony of Van Diemen’s Land. -

A Phylogeny and Timescale for Marsupial Evolution Based on Sequences for Five Nuclear Genes

J Mammal Evol DOI 10.1007/s10914-007-9062-6 ORIGINAL PAPER A Phylogeny and Timescale for Marsupial Evolution Based on Sequences for Five Nuclear Genes Robert W. Meredith & Michael Westerman & Judd A. Case & Mark S. Springer # Springer Science + Business Media, LLC 2007 Abstract Even though marsupials are taxonomically less diverse than placentals, they exhibit comparable morphological and ecological diversity. However, much of their fossil record is thought to be missing, particularly for the Australasian groups. The more than 330 living species of marsupials are grouped into three American (Didelphimorphia, Microbiotheria, and Paucituberculata) and four Australasian (Dasyuromorphia, Diprotodontia, Notoryctemorphia, and Peramelemorphia) orders. Interordinal relationships have been investigated using a wide range of methods that have often yielded contradictory results. Much of the controversy has focused on the placement of Dromiciops gliroides (Microbiotheria). Studies either support a sister-taxon relationship to a monophyletic Australasian clade or a nested position within the Australasian radiation. Familial relationships within the Diprotodontia have also proved difficult to resolve. Here, we examine higher-level marsupial relationships using a nuclear multigene molecular data set representing all living orders. Protein-coding portions of ApoB, BRCA1, IRBP, Rag1, and vWF were analyzed using maximum parsimony, maximum likelihood, and Bayesian methods. Two different Bayesian relaxed molecular clock methods were employed to construct a timescale for marsupial evolution and estimate the unrepresented basal branch length (UBBL). Maximum likelihood and Bayesian results suggest that the root of the marsupial tree is between Didelphimorphia and all other marsupials. All methods provide strong support for the monophyly of Australidelphia. Within Australidelphia, Dromiciops is the sister-taxon to a monophyletic Australasian clade. -

Thylacinidae

FAUNA of AUSTRALIA 20. THYLACINIDAE JOAN M. DIXON 1 Thylacine–Thylacinus cynocephalus [F. Knight/ANPWS] 20. THYLACINIDAE DEFINITION AND GENERAL DESCRIPTION The single member of the family Thylacinidae, Thylacinus cynocephalus, known as the Thylacine, Tasmanian Tiger or Wolf, is a large carnivorous marsupial (Fig. 20.1). Generally sandy yellow in colour, it has 15 to 20 distinct transverse dark stripes across the back from shoulders to tail. While the large head is reminiscent of the dog and wolf, the tail is long and characteristically stiff and the legs are relatively short. Body hair is dense, short and soft, up to 15 mm in length. Body proportions are similar to those of the Tasmanian Devil, Sarcophilus harrisii, the Eastern Quoll, Dasyurus viverrinus and the Tiger Quoll, Dasyurus maculatus. The Thylacine is digitigrade. There are five digital pads on the forefoot and four on the hind foot. Figure 20.1 Thylacine, side view of the whole animal. (© ABRS)[D. Kirshner] The face is fox-like in young animals, wolf- or dog-like in adults. Hairs on the cheeks, above the eyes and base of the ears are whitish-brown. Facial vibrissae are relatively shorter, finer and fewer than in Tasmanian Devils and Quolls. The short ears are about 80 mm long, erect, rounded and covered with short fur. Sexual dimorphism occurs, adult males being larger on average. Jaws are long and powerful and the teeth number 46. In the vertebral column there are only two sacrals instead of the usual three and from 23 to 25 caudal vertebrae rather than 20 to 21. -

Venomous Collections Kenneth D

Venomous collections Kenneth D. Winkel and Jacqueline Healy In many countries now, Stanley Cohen’s discovery of growth his work on anaphylaxis.3 Richet’s research in Universities is factors, and the 2003 chemistry work commenced with the study of under severe financial restraint. prize for Roderick MacKinnon’s the effects of jellyfish venom and led This is a short-sighted policy. structural and mechanistic studies to a new understanding of allergy. Ways have to be found to of ion channels.2 Moreover, venoms Although the scientific utility and maintain University research contributed, from ‘improbable societal fascination with venoms, untrammelled by requirements beginnings’ through ‘convoluted and venomous creatures, predates of forecasting application or pathways’, to early Nobel Prizes such the University of Melbourne, this usefulness. Those who wish to as Charles Richet’s 1913 physiology ancient theme finds expression study the sex-life of butterflies, or medicine prize in recognition of through many of its collections. or the activities associated with snake venom or seminal fluid should be encouraged to do so. It is such improbable beginnings that lead by convoluted pathways to new concepts and then, perhaps some 20 years later, to new types of drugs. —John R. Vane, 19821 More than 30 years after Nobel Prize-winner John Vane’s invocation concerning the value of curiosity- driven research, including allusion to the role snake venom played in his pathway to pharmacological discovery, this sentiment remains just as relevant. Indeed, at least two subsequent Nobel Prizes involved the use of venoms or toxins as key sources of bioactive compounds or critical molecular probes of structure-function relationships: the 1986 physiology or medicine prize for Rita Levi-Montalcini’s and Kenneth D. -

NEWSLETTER 2011 年 4 月 Vol. 3

NEWSLETTER 2011 年 4 月 Vol. 3 To Supporters of the AJWCEF Tetsuo Mizuno, Managing Director Thank you for your understanding of and cooperation towards the Australia-Japan Wildlife Conservation and Education Foundation. Looking back over the past year, in August the Foundation was fortunate to receive some funding for its activities from the Australian Commonwealth Government via a grant from the Australia Japan Foundation. We participated in our first international conference (the 10th Conference of Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity, COP10) and, as a result, were able to register with the Head Office for the Convention on Biological Diversity, an organ of the United Nations. As part of our activities to educate about wildlife conservation, an important element of our work, at COP10 the Foundation presented research papers at a side event to the main conference, had a display booth and conducted a citizens’ forum to disseminate information more widely to the general public. We also visited several universities in Japan to present seminars on the current state of wildlife in Australia and their protection, etc. These were well attended, with close to 100 students gathering at some venues, and it was truly significant to be able to speak with the youth of the next generation. Currently we have two projects underway, one being the establishment of an international artificial insemination network and gene bank to maintain a healthy genetic diversity among the Australian animals that have been sent to zoos overseas. The other is eucalyptus plantations for the purpose of securing food for injured and sick wild koalas that have been hospitalized. -

Annual Waterways Report

Annual Waterways Report Pieman Catchment Water Assessment Branch 2009 ISSN: 1835-8489 Copyright Notice: Material contained in the report provided is subject to Australian copyright law. Other than in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968 of the Commonwealth Parliament, no part of this report may, in any form or by any means, be reproduced, transmitted or used. This report cannot be redistributed for any commercial purpose whatsoever, or distributed to a third party for such purpose, without prior written permission being sought from the Department of Primary Industries and Water, on behalf of the Crown in Right of the State of Tasmania. Disclaimer: Whilst DPIW has made every attempt to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information and data provided, it is the responsibility of the data user to make their own decisions about the accuracy, currency, reliability and correctness of information provided. The Department of Primary Industries and Water, its employees and agents, and the Crown in the Right of the State of Tasmania do not accept any liability for any damage caused by, or economic loss arising from, reliance on this information. Department of Primary Industries and Water Pieman Catchment Contents 1. About the catchment 2. Streamflow and Water Allocation 3. River Health 1. About the catchment The Pieman catchment drains a land mass of more than 4,100 km 2 stretching from about Lake St Clair in the Central Highlands west more than 90 km to Granville Harbour on the rugged West Coast of Tasmania. Major rivers draining the catchment are the Savage, Donaldson and Whyte rivers in the lower catchment, the Pieman, Huskisson rivers in the middle catchment and the Mackintosh, Murchison and Anthony rivers in the upper catchment. -

Provision of Professional Services Western Tasmania Industry Infrastructure Study TRIM File No.: 039909/002 Brief No.: 1280-3-19 Project No.: A130013.002

Provision of Professional Services Western Tasmania Industry Infrastructure Study TRIM File No.: 039909/002 Brief No.: 1280-3-19 Project No.: A130013.002 Western Tasmania Industry Infrastructure Study FINAL REPORT May 2012 Sinclair Knight Merz 100 Melville St, Hobart 7000 GPO Box 1725 Hobart TAS 7001 Australia Tel: +61 3 6221 3711 Fax: +61 3 6224 2325 Web: www.skmconsulting.com COPYRIGHT: The concepts and information contained in this document are the property of Sinclair Knight Merz Pty Ltd. Use or copying of this document in whole or in part without the written permission of Sinclair Knight Merz constitutes an infringement of copyright. LIMITATION: This report has been prepared on behalf of and for the exclusive use of Sinclair Knight Merz Pty Ltd’s Client, and is subject to and issued in connection with the provisions of the agreement between Sinclair Knight Merz and its Client. Sinclair Knight Merz accepts no liability or responsibility whatsoever for or in respect of any use of or reliance upon this report by any third party. The SKM logo trade mark is a registered trade mark of Sinclair Knight Merz Pty Ltd. Final Report Contents Executive Summary 1 1. Introduction and background 13 1.1. Strategic background 13 1.2. Policy and planning framework 14 1.3. This report 15 1.4. Approach adopted 16 2. Report 1: Infrastructure audit report 17 2.1. Introduction 17 2.2. Road Infrastructure 17 2.2.1. Roads Policy and Planning Context 17 2.2.2. Major Road Corridor 20 2.2.2.1. Anthony Main Road (DIER) 20 2.2.2.2. -

3966 Tour Op 4Col

The Tasmanian Advantage natural and cultural features of Tasmania a resource manual aimed at developing knowledge and interpretive skills specific to Tasmania Contents 1 INTRODUCTION The aim of the manual Notesheets & how to use them Interpretation tips & useful references Minimal impact tourism 2 TASMANIA IN BRIEF Location Size Climate Population National parks Tasmania’s Wilderness World Heritage Area (WHA) Marine reserves Regional Forest Agreement (RFA) 4 INTERPRETATION AND TIPS Background What is interpretation? What is the aim of your operation? Principles of interpretation Planning to interpret Conducting your tour Research your content Manage the potential risks Evaluate your tour Commercial operators information 5 NATURAL ADVANTAGE Antarctic connection Geodiversity Marine environment Plant communities Threatened fauna species Mammals Birds Reptiles Freshwater fishes Invertebrates Fire Threats 6 HERITAGE Tasmanian Aboriginal heritage European history Convicts Whaling Pining Mining Coastal fishing Inland fishing History of the parks service History of forestry History of hydro electric power Gordon below Franklin dam controversy 6 WHAT AND WHERE: EAST & NORTHEAST National parks Reserved areas Great short walks Tasmanian trail Snippets of history What’s in a name? 7 WHAT AND WHERE: SOUTH & CENTRAL PLATEAU 8 WHAT AND WHERE: WEST & NORTHWEST 9 REFERENCES Useful references List of notesheets 10 NOTESHEETS: FAUNA Wildlife, Living with wildlife, Caring for nature, Threatened species, Threats 11 NOTESHEETS: PARKS & PLACES Parks & places, -

Aquila 23. Évf. 1916

A madarak palaeontologiájának története és irodalma. Irta : DR. Lambrecht Kálmán. Minden ismeret történetének eredete többé-kevésbbé homályba vész. Az els úttörk még maguk is csak tapogatóznak; leírásaik — a kezdet nehézségeivel küzdve — nem szabatosak, több bennük a sej- dít, mint a positiv elem. Fokozottan áll ez a palaeontologiára, amely- nek gyakran bizony igen hiányos anyaga gazdag recens összehasonlító anyagot és alapos morphologiai ismereteket igényel. A palaeontologia legismertebb történetíróinak, MARSH-nak^ és ZiTTEL-nek2 chronologiai beosztásait figyelmen kívül hagyva, ehelyütt Abel3 szellemes beosztását fogadjuk el és megkülönböztetünk a madár- palaeontologia történetében 1. phantasticus, 2. descriptiv és 3. morpho- logiai és phylogenetikai periódust. Nagyon természetes, hogy a fossilis madarak ismerete karöltve haladt a recens madarak osteologiájának megismerésével, 4 mert a palaeon- tologus csakis recens comparativ anyag és vizsgálatok alapján foghat munkához. De viszont igaz az is, hogy a morphologus sem mozdulhat meg az si alakok vázrendszerének ismerete nélkül, nem is szólva arról, hogy a gyakran nagyon töredékes fossilis maradványok mennyi érdekes morphologiai megfigyelésre vezették már a búvárokat. A phantasticus periódus. Ez a periódus, amely — összehasonlítás hiján — túlnyomóan speculativ alapon mvelte a tudományt, a XVIll. századdal, vagyis CuviER felléptével végzdik. Eltekintve Albertus MAGNUS-nak (1193—1280, Marsh szerint 1 Marsh, 0. C, Geschichte und Methode der paläoiitologischen Entdeckungen. — Kosmos VI. 1879. -

Annual Planning Report 2020

ANNUAL PLANNING REPORT 2020 Feedback and enquiries We welcome feedback and enquiries on our 2020 APR, particularly from anyone interested in discussing opportunities for demand management or other innovative solutions to manage limitations. Please send feedback and enquiries to: [email protected] Potential demand management solution providers can also register with us via our demand management register on our website at https://www.tasnetworks.com.au/demand-management-engagement-register 1. Introduction 2 2. Network transformation 12 3. Transmission network development 22 4. Area planning constraints and developments 36 5. Network performance 66 6. Tasmanian power system 82 7. Information for new transmission network connections 96 Glossary 106 Abbreviations 109 Appendix A Regulatory framework and planning process 110 Appendix B Incentive Schemes 117 Appendix C Generator information 118 Appendix D Distribution network reliability performance measures and results 120 Appendix E Power quality planning levels 123 TASNETWORKS ANNUAL PLANNING REPORT 2020 1 1. Introduction Tasmania is increasing its contribution to a This transition, with the move to increased low cost, renewable energy based electricity interconnection and variable renewable energy sector and being a major contributor to generation, is fundamentally changing how the firming electricity supply across the National power system operates. We, in conjunction with Electricity Market (NEM). As a key part of this the broader Tasmanian electricity industry, have objective, we present the Tasmanian Networks Pty managed this situation well to date, however the Ltd (TasNetworks) Annual Planning Report (APR). diligence must continue and solutions to new As the Tasmanian jurisdictional Transmission and challenges identified to keep pace with change. -

Dexter the Courageous Koala Is Suitable for Readers from Year 5 Up, Although Mature, Capable Readers in Years 3 and 4 Will Also Find Much to Enjoy

Dexter The Courageous Koala By Jesse Blackadder Book Summary: Ashley can’t wait to bring home the puppy she’s been promised —but then Dad loses his job, and her parents can’t afford an extra mouth to feed. Heart-broken, Ashley reluctantly goes off to spend the school holidays with an aunt she barely knows—eccentric Micky, who lives in an isolated spot on the north coast of NSW and who cares for injured koalas. Within hours of arriving, the road into Micky’s house is cut off by rising flood waters, then a wild storm brings a blackout and some serious damage to Micky’s house and garden. Worse still, trees from a nearby koala colony have come down in the storm, and Ashley must risk life and limb to save an injured koala and her joey. Curriculum Areas and Key Learning Outcomes: Dexter the Courageous Koala is suitable for readers from Year 5 up, although mature, capable readers in Years 3 and 4 will also find much to enjoy. ACELT1609,ACELT1795,ACELT1610 ISBN: 9780733331787 ACELY1698,ACELY1701,ACELY1703 eBook 9781743098202 ACELY1704,ACELT1613,ACELT1800 ACELY1710,ACSSU043,ACSSU094 Notes by: Judith Ridge ACHCK027,ACHGK030,ACHGK028 Appropriate Ages: 8-13 These notes may be reproduced free of charge for use and study within schools but they may not be reproduced (either in whole or in part) and offered for commercial sale. Page 1 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Jesse Blackadder is an award-winning author for children and adults. She lives on the far north coast of NSW—the same area that Dexter the Courageous Koala is set—where she shares a large garden with a variety of wildlife, including passing koalas. -

The Earliest Motion Picture Footage of the Last Captive Thylacine? Stephen R

The earliest motion picture footage of the last captive thylacine? Stephen R. Sleightholme1 and Cameron R. Campbell2 1 Project Director - International Thylacine Specimen Database (ITSD), 26 Bitham Mill, Westbury, BA13 3DJ, UK. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Curator of the online Thylacine Museum: http://www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/ 8707 Eagle Mountain Circle, Fort Worth, TX 76135, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/australian-zoologist/article-pdf/37/3/282/1587738/az_2014_021.pdf by guest on 02 October 2021 David Fleay’s 1933 motion film footage of the last captive thylacine at the Beaumaris Zoo in Hobart was thought to be the only film record of this thylacine. The authors provide evidence to confirm that two earlier motion picture films, erroneously dated to 1928, also show the last captive specimen at the zoo. ABSTRACT Key Words: Thylacine, Thylacinus cynocephalus, motion picture, Beaumaris Zoo, David Fleay. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7882/AZ.2014.021 Introduction The thylacine or Tasmanian tiger (Thylacinus cynocephalus) is the largest marsupial carnivore to have existed into modern times. The last known captive specimen, a male (Sleightholme, 2011), died at the Beaumaris Zoo on the Queen’s Domain in Hobart on the night of the 7th September 1936. There are seven historical motion picture films known to exist of captive thylacines, all of which were made between 1911 and 1933 (Fig. 1, [i-vii]) 1. Five of the films were recorded at the Beaumaris Zoo in Hobart, and the remaining two at the London Zoo, Regent’s Park. The earliest known footage was filmed by a Mr.