Cli-Je: Subjectivity and Publicity in Art and Criticism the Letters of Pierre Restany and Marcel Broodthaers in Court-Circuit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

H-France Review Volume 11 (2011) Page 1

H-France Review Volume 11 (2011) Page 1 H-France Review Vol. 11 (October 2011), No. 220 Jill Carrick, Nouveau Réalisme, 1960s France, and the Neo-avant-garde. Topographies of Chance and Return. Aldershot and Burlington: Ashgate Publishing, 2010. xii + 184 pp. B&w illustrations, facsimilies, plan, bibliography and index. $104.95 U.S. (hb). ISBN 978-0-7546-6141-2 Review by Sarah Wilson, Courtauld Institute of Art This is a fascinating book: the first critical exposé in English of French critic Pierre Restany’s Nouveau réalisme movement, baptised in 1960, which ran parallel to American Pop but was ambivalent about Americanisation, a highly political issue. It was only in 2007 that a major exhibition at the Grand Palais did justice to the group as a whole, following a retrospective at the Musée de la Ville de Paris in 1986; the Centre Pompidou has recently staged a series of superb monographic shows of Nouveau Réaliste artists: Yves Klein, Jacques Villeglé and Arman. Like Pop, this movement broke from traditional School of Paris painting or sculpture which kept to traditional materials and modernist aesthetics of representation and abstraction. It introduced what Restany called la prise sociologique du réel: a ‘sociological’ engagement with real life into art, in the living presence of Marcel Duchamp, dada inventor of the ‘readymade’ before the First World War. Restany’s show ‘40 degrees above Dada’ of May 1961 acknowledges this paternity. To visual art one can add the new emphasis on ‘things’ in the French novel or the writings of Georges Perec, and the theoretical emphasis of ‘everyday life’ in Henri Lefebvre or the young Pierre Bourdieu; a heady ambient discourse that distinguishes Nouveau Réalisme from the pragmatic relations with objects of contemporary American artists such as Robert Rauschenburg. -

The Body in Art

THE BODY IN ART MEDIATION FORM INTRODUCTION First subjected to aesthetic canons, the represented body gradually freed itself from classical values. The modern era marks a challenge to the ideal of beauty, even freeing itself from representation. From then on, the body was distorted, dislocated, stylized, transformed, shaking up the pictorial and sculptural representation of the 20th century. Beyond the representation itself, the body becomes a tool, a trace and an imprint, the artist puts his own body into play. This visit through the works in the permanent collection allows us to follow the changes in this major subject of 20th century art. Duration of the tour • Primary School 1H • Middle School 1H • High School / College 1H Objectives • To discover the different representations of the human body • Discover color as a component of the 2 artwork • Learn to understand an artwork • Familiarization with the specific vocabulary of art A STEPSA OF THE VISIT Based on this information, the teacher will have to make a choice of steps according to the level of the class and the availability of the artworks in the room. The stages can be adjusted at the convenience of the teachers. The arrival preparation form must be completed. Step 1: Representation of the body Step 2: emancipation of the body Step 3: the body at work B RELATEDA KNOWLEDGE A STEPSA OF THE VISIT STEP 1: REPRESENTATION OF THE BODY With modernity, artists are trying to shake up the traditional codes of representation of the body. Attacking figurative codes, beauty, proportion and ideas of likelihood, the artists propose a completely different range of images based on industrial and modern production techniques. -

The Ideology and Praxis of Nouveau Réalisme, RIHA Journal 0051

RIHA Journal 0051 | 10 August 2012 Poetic Recuperations: The Ideology and Praxis of Nouveau Réalisme Wood Roberdeau Editing and peer review managed by: Caroline Arscott, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London Reviewers: Jill Carrick, Anthony Gardner Abstract Taking previously un-translated writings of critic Pierre Restany as a primary source, this article demonstrates how his vision for the Nouveau Réaliste movement of the 1950s and 1960s demands a detailed and theoretical (rather than historically contextual) exploration of its attempt to reconcile visual art with the quotidian. Accordingly, Bürger's criticism of the historical and neo-avant-gardes is weighed against theories of aesthetics and politics from Adorno to Rancière. In addition, Heidegger's work on the art object, alongside Benjamin's interest in Hölderlin, serves to inform an analysis of Restany's investment in a concept of the 'poetry of the real'. Individual works by Niki de Saint- Phalle, Daniel Spoerri and Yves Klein are also investigated as exemplars of the Nouveau Réaliste ideology. My interest in Restany's life and work stems from recent art world concentrations on the banal or 'infra-ordinary' and its relation to similar concerns within sociology. Contents Introduction Revaluating the Neo-avant-garde Aesthetics and Politics Countertopographies Mining the Poetic Intuitive Gestures Everyday Deviance Introduction [1] The subject of the everyday is a popular one in many fields, and one that is so expansive that it is nearly impossible to pinpoint any definitive characteristic for its long-time incorporation within the visual arts. If viewed through a sociological lens however, it becomes less difficult to understand the potential for reciprocity between high culture and the mundane. -

Pierre Restany: Para Além Do Real Um Estudo Sobre O Novo Realismo E Sua Conexão Com a X Bienal De São Paulo (1969)

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE JUIZ DE FORA INSTITUTO DE ARTES E DESIGN – IAD PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ARTES, CULTURA E LINGUAGENS CLAUDIO DE MELO FILHO Pierre Restany: para além do real Um estudo sobre o Novo Realismo e sua conexão com a X Bienal de São Paulo (1969) JUIZ DE FORA 2019 Claudio de Melo Filho Pierre Restany: para além do real Um estudo sobre o Novo Realismo e sua conexão com a X Bienal de São Paulo (1969) Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Artes, Cultura e Linguagens (PPG/ACL). Linha de Pesquisa: Arte, Moda: História e Cultura. no Instituto de Artes e Design (IAD) da Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora. Orientadora: Profª Drª Renata Cristina de Oliveira Maia Zago JUIZ DE FORA 2019 Pierre Restany AGRADECIMENTOS À minha orientadora, Renata Cristina de Oliveira Maia Zago, cujo encontro de almas proporcionou alegrias que irão durar por muitos e muitos anos; À banca de qualificação e defesa: Maria Lúcia Bueno Ramos, que além das contribuições pertinentes e amizade, me proporcionou ensinamentos pessoais durantes os anos de graduação e à Caroline Saut Schroeder, cuja pesquisa sobre à X Bienal foi inspiradora para a construção dessa dissertação; À professora Raquel Quinet Pifano, quem me nutriu de todo pensamento acerca da estética e crítica das artes, além de profundas alegrias e carinho durante todos os meus anos nesta instituição; Aos meus incomparáveis amigos: Daniela Lima, Thamara Venâncio - a pós-graduação nos uniu em um caminho cheio de alegrias, tristezas, risadas e muitos abraços, Fabiana Panini, Mariana Reis e todos os amigos de Juiz de Fora; Aos meus pais e irmãos, Cláudio, Rozária, Ícaro e Iara, que iluminam meu caminho; À todos os professores e às secretárias Lara Velloso e Flaviana Polisseni, do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Artes, Cultura e Linguagens; À Rose, da cantina, por me proporcionar incontáveis risadas regadas a cafézinhos; Aos Funcionários do Arquivo Histórico Wanda Svevo, da Fundação Bienal de São Paulo; À bolsa concedida pela UFJF durante um ano deste percursso; E a muitos outros.. -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Dematerialization in the Argentine Context : Experiments in the Avant-garde in the 1960s Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/31p8448f Author Mazadiego, Elize M. Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Dematerialization in the Argentine Context: Experiments in the Avant-garde in the 1960s A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Art History, Theory, and Criticism by Elize M. Mazadiego Committee in charge: Professor W. Norman Bryson, Co-Chair Professor Grant Kester, Co-Chair Professor Steve Fagin Professor Ruben Ortiz-Torres Professor Emily Roxworthy 2015 Copyright Elize M. Mazadiego, 2015 All Rights Reserved. The Dissertation of Elize M. Mazadiego is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ____________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________ Co-Chair ____________________________________________________________ Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2015 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ................................................................................................................... iii Table -

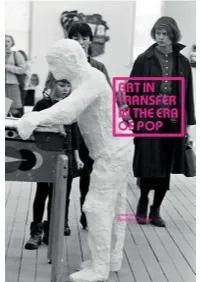

Art in Transfer in the Era of Pop

ART IN TRANSFER IN THE ERA OF POP ART IN TRANSFER IN THE ERA OF POP Curatorial Practices and Transnational Strategies Edited by Annika Öhrner Södertörn Studies in Art History and Aesthetics 3 Södertörn Academic Studies 67 ISSN 1650-433X ISBN 978-91-87843-64-8 This publication has been made possible through support from the Terra Foundation for American Art International Publication Program of the College Art Association. Södertörn University The Library SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications © The authors and artists Copy Editor: Peter Samuelsson Language Editor: Charles Phillips, Semantix AB No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Cover Image: Visitors in American Pop Art: 106 Forms of Love and Despair, Moderna Museet, 1964. George Segal, Gottlieb’s Wishing Well, 1963. © Stig T Karlsson/Malmö Museer. Cover Design: Jonathan Robson Graphic Form: Per Lindblom & Jonathan Robson Printed by Elanders, Stockholm 2017 Contents Introduction Annika Öhrner 9 Why Were There No Great Pop Art Curatorial Projects in Eastern Europe in the 1960s? Piotr Piotrowski 21 Part 1 Exhibitions, Encounters, Rejections 37 1 Contemporary Polish Art Seen Through the Lens of French Art Critics Invited to the AICA Congress in Warsaw and Cracow in 1960 Mathilde Arnoux 39 2 “Be Young and Shut Up” Understanding France’s Response to the 1964 Venice Biennale in its Cultural and Curatorial Context Catherine Dossin 63 3 The “New York Connection” Pontus Hultén’s Curatorial Agenda in the -

Made in Nice

MADE IN NICE MEDIATION FORM PRESENTATION Students will discover the artistic bubbling of Nice that appeared in the 1960s through the works in the permanent collection. This selection allows us to understand what the young local creation was like. The École de Nice, more a name than a defined aesthetic trend, is based on artists who worked on the territory nearly 60 years ago, independently of other movements to which some are linked, such as the New Realism, Supports-Surfaces, Fluxus or Group 70. These years testify to a real artistic emulation in the Nice region. Duration of the tour • Primary School 1H • Middle School 1H • High School / College 1H Objectives • Define "the Nice school" • Discover local artists • Show the influence and artistic emulation of the Nice region • Learn to read a work of art • Familiarization with the vocabulary specific to art 1 A STEPSA OF THE VISIT Based on this information, the teacher will have to make a choice of steps according to the level of the class and the availability of the artworks in the room. The stages can be adjusted at the convenience of the teachers. The arrival preparation form must be completed. Step 1: A school ? Step 2: Artistic gestures Step 3: New Places B RELATEDA KNOWLEDGE A STEPSA OF THE VISIT STEP 1: A SCHOOL? The mention "École de Nice" appeared for the first time in Combat magazine in 1960, under the pen of Claude Rivière. While critics agree, in order to recognize the reality and relevance of a phenomenon in Nice, many are sceptical about its coherence as a movement and a "school". -

Twentieth-Century Art: 1945-2000

NATASHA RUIZ-GÓMEZ History of Art Department University of Pennsylvania Fall 2005 – CGS/ARTH 287.601 Thursdays 5:30–8:30 PM Jaffe 113 TWENTIETH-CENTURY ART: 1945-2000 After the second World War, the center of the art world shifted from Paris to New York. This course will consider the provocative, contentious, and complex art made during the second half of the twentieth century. A few of the themes we will consider are the advent of postmodernism, the rise of kitsch, the increasing politicization of the artist, the inclusion of the body in art-making, the emergence of site-specificity, and the spaces in which art is produced and viewed. COURSE SCHEDULE September 8 – Introduction September 15 – Abstract Expressionism (Action Painting and Color Field Painting) and Sculpture Reading: Harold Rosenberg, “The American Action Painters” [1952], Tradition of the New (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1965) 23-39. Reading: Clement Greenberg, “Modernist Painting,” Arts Yearbook 4 (1961): 102-108. Reading: Anne Wagner, “Pollock’s Nature, Frankenthaler’s Culture,” Jackson Pollock: New Approaches, eds. Kirk Varnedoe and Pepe Karmel (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1999) 181-200. Suggested Reading: Fineberg 67-128. September 22 – Johns, Rauschenberg, and Pop Art Reading: Clement Greenberg, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” [1939], Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism, ed. John O’Brian, vol. I. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1986) 5-22. Reading: Leo Steinberg, “The Flatbed Picture Plane” (excerpt) and “Jasper Johns: The First Seven Years of His Art,” Other Criteria: Confrontations with Twentieth-Century Art (London: Oxford University Press, 1972) 82-91 and 17-54. -

Jean-Noel Archive.Qxp.Qxp

THE JEAN-NOËL HERLIN ARCHIVE PROJECT Jean-Noël Herlin New York City 2005 Table of Contents Introduction i Individual artists and performers, collaborators, and groups 1 Individual artists and performers, collaborators, and groups. Selections A-D 77 Group events and clippings by title 109 Group events without title / Organizations 129 Periodicals 149 Introduction In the context of my activity as an antiquarian bookseller I began in 1973 to acquire exhibition invitations/announcements and poster/mailers on painting, sculpture, drawing and prints, performance, and video. I was motivated by the quasi-neglect in which these ephemeral primary sources in art history were held by American commercial channels, and the project to create a database towards the bibliographic recording of largely ignored material. Documentary value and thinness were my only criteria of inclusion. Sources of material were random. Material was acquired as funds could be diverted from my bookshop. With the rapid increase in number and diversity of sources, my initial concept evolved from a documentary to a study archive project on international visual and performing arts, reflecting the appearance of new media and art making/producing practices, globalization, the blurring of lines between high and low, and the challenges to originality and quality as authoritative criteria of classification and appreciation. In addition to painting, sculpture, drawing and prints, performance and video, the Jean-Noël Herlin Archive Project includes material on architecture, design, caricature, comics, animation, mail art, music, dance, theater, photography, film, textiles and the arts of fire. It also contains material on galleries, collectors, museums, foundations, alternative spaces, and clubs. -

On the Reception of Pop Art in Belgium (Brüssel, 1-2 Dec 11)

Pop? On the reception of Pop art in Belgium (Brüssel, 1-2 Dec 11) Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Dec 1–02, 2011 Carl Jacobs, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium On 1 and 2 December 2011 the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium organise the international symposium “Pop? On the reception of Pop Art in Belgium (1960-1970)”. At this symposium, inter- nationally renowned lecturers and young researchers will focus on the reception of Pop Art in Bel- gium and Europe. How was America related to Europe? When did the European art scene shifted its interest in new aesthetic developments from Paris to New York? In which way did young artists responded to new Trans-Atlantic stimuli? Thanks to contributions from England, France, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium, completed with a call for papers addressed to young researchers, this symposium is bound to provide stimulating answers to these questions. At this symposium, research on the local developments in European art from the 1960s aspires to redirect the inter- pretation of the driving forces and the development of the Belgian and European art world. Pop Art: a global art Pop art is one of world’s most imaginative cultural and artistic movements from the post-war era. Grown out of the Anglo-Saxon world, it originated at almost the same time in both the United King- dom and the United States of America. In the USA, icons like Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein and Claes Oldenburg started to depict the contemporary consumer society in a brutal, figurative and industrial way. -

Fluxus : Selections from the Gilbert and Lila Silverman Collection Clive Phillpot and Jon Hendricks

Fluxus : selections from the Gilbert and Lila Silverman Collection Clive Phillpot and Jon Hendricks. -- Author Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.) Date 1988 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art ISBN 0870703110 Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2141 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art SELECTIONSFROM THE GILBERT AND LILA SILVERMAN COLLECTION I Museum Of Modern art THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART NEW YORK Fluxus Mani f esfo J „ Med To cause a (i.scjHtrgeiron^gs in purging. ' frku'slf,UJM?ofrc^r"sryiUT\fed flow! See ?LUENT^cV fiU a A flowing or fluid discharge from the bowels or oiht aenbC,^V^ > &S: as. th CX dysentery, b Thejnattpr thus discharged. f Purge -fire a/or Id 0 bourgeois si excess intellectual " profes siona/ A com merc/'cr //z e<d Culture.^ PUPGE the wor/d of dead art , imitation t art i ficial art", abstract art illusionistic art; mathematical art; PUZ6E THE WOTLT> pF "FUPoFAE/SM " / ; HjjL. 2. Act of flowing; a continuous moving on or passing by, as of a flowing stream; a continuing succession of changes. 3. A stream; copious flow; flood; outflow. 4. The setting in of the tide toward the shore. Cf. heflux. 5. State of being liquid through heat; fusion. Rare. FKomotf A FevoLvti o i\ja P Y Floor? ANF? TITTF ilu AFT, Promote In'inaj art , an ti - ant , promo te NOKJ APT PEALlTY to be folly cjras ped -

Giuseppe Panza Papers, 1956-1990

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf8n39n9g1 No online items Finding aid for the Giuseppe Panza papers, 1956-1990 Lynda Bunting. Finding aid for the Giuseppe 940004 1 Panza papers, 1956-1990 Descriptive Summary Title: Giuseppe Panza papers Date (inclusive): 1956-1990 Number: 940004 Creator/Collector: Panza, Giuseppe Physical Description: 117 Linear Feet(311 boxes, 58 rolls, 3 flat file folders) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Collection documents the Italian businessman's activities in collecting works by some of the seminal American artists involved with abstract expressionist, pop, minimal, conceptual, environmental, and light and space art. The archive contains material dating from 1956, when Panza began collecting. up to the sale of the second part of his collection to the Guggenheim Museum in 1990. Panza's art collection is documented by correspondence with artists and galleries, photographs, small drawings, invoices, loan requests, announcements, and invitations. The archive also includes a substantial quantity of Panza's writings on art; papers and ephemera related to Panza's associations with museums, galleries, and cultural institutions; clippings and photocopies of articles about the collection; and an extensive group of architectural drawings of potential sites for the collection, many with Panza's installation designs. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English and Italian. 1923 Born March 23rd in Milan.