Incorporating Molecular Data in Fungal Systematics: a Guide for Aspiring Researchers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selecting Molecular Markers for a Specific Phylogenetic Problem

MOJ Proteomics & Bioinformatics Review Article Open Access Selecting molecular markers for a specific phylogenetic problem Abstract Volume 6 Issue 3 - 2017 In a molecular phylogenetic analysis, different markers may yield contradictory Claudia AM Russo, Bárbara Aguiar, Alexandre topologies for the same diversity group. Therefore, it is important to select suitable markers for a reliable topological estimate. Issues such as length and rate of evolution P Selvatti Department of Genetics, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, will play a role in the suitability of a particular molecular marker to unfold the Brazil phylogenetic relationships for a given set of taxa. In this review, we provide guidelines that will be useful to newcomers to the field of molecular phylogenetics weighing the Correspondence: Claudia AM Russo, Molecular Biodiversity suitability of molecular markers for a given phylogenetic problem. Laboratory, Department of Genetics, Institute of Biology, Block A, CCS, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Fundão Island, Keywords: phylogenetic trees, guideline, suitable genes, phylogenetics Rio de Janeiro, RJ, 21941-590, Brazil, Tel 21 991042148, Fax 21 39386397, Email [email protected] Received: March 14, 2017 | Published: November 03, 2017 Introduction concept that occupies a central position in evolutionary biology.15 Homology is a qualitative term, defined by equivalence of parts due Over the last three decades, the scientific field of molecular to inherited common origin.16–18 biology has experienced remarkable advancements -

An Automated Pipeline for Retrieving Orthologous DNA Sequences from Genbank in R

life Technical Note phylotaR: An Automated Pipeline for Retrieving Orthologous DNA Sequences from GenBank in R Dominic J. Bennett 1,2,* ID , Hannes Hettling 3, Daniele Silvestro 1,2, Alexander Zizka 1,2, Christine D. Bacon 1,2, Søren Faurby 1,2, Rutger A. Vos 3 ID and Alexandre Antonelli 1,2,4,5 ID 1 Gothenburg Global Biodiversity Centre, Box 461, SE-405 30 Gothenburg, Sweden; [email protected] (D.S.); [email protected] (A.Z.); [email protected] (C.D.B.); [email protected] (S.F.); [email protected] (A.A.) 2 Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Gothenburg, Box 461, SE-405 30 Gothenburg, Sweden 3 Naturalis Biodiversity Center, P.O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands; [email protected] (H.H.); [email protected] (R.A.V.) 4 Gothenburg Botanical Garden, Carl Skottsbergsgata 22A, SE-413 19 Gothenburg, Sweden 5 Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, 26 Oxford St., Cambridge, MA 02138 USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 28 March 2018; Accepted: 1 June 2018; Published: 5 June 2018 Abstract: The exceptional increase in molecular DNA sequence data in open repositories is mirrored by an ever-growing interest among evolutionary biologists to harvest and use those data for phylogenetic inference. Many quality issues, however, are known and the sheer amount and complexity of data available can pose considerable barriers to their usefulness. A key issue in this domain is the high frequency of sequence mislabeling encountered when searching for suitable sequences for phylogenetic analysis. -

"Phylogenetic Analysis of Protein Sequence Data Using The

Phylogenetic Analysis of Protein Sequence UNIT 19.11 Data Using the Randomized Axelerated Maximum Likelihood (RAXML) Program Antonis Rokas1 1Department of Biological Sciences, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee ABSTRACT Phylogenetic analysis is the study of evolutionary relationships among molecules, phenotypes, and organisms. In the context of protein sequence data, phylogenetic analysis is one of the cornerstones of comparative sequence analysis and has many applications in the study of protein evolution and function. This unit provides a brief review of the principles of phylogenetic analysis and describes several different standard phylogenetic analyses of protein sequence data using the RAXML (Randomized Axelerated Maximum Likelihood) Program. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 96:19.11.1-19.11.14. C 2011 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Keywords: molecular evolution r bootstrap r multiple sequence alignment r amino acid substitution matrix r evolutionary relationship r systematics INTRODUCTION the baboon-colobus monkey lineage almost Phylogenetic analysis is a standard and es- 25 million years ago, whereas baboons and sential tool in any molecular biologist’s bioin- colobus monkeys diverged less than 15 mil- formatics toolkit that, in the context of pro- lion years ago (Sterner et al., 2006). Clearly, tein sequence analysis, enables us to study degree of sequence similarity does not equate the evolutionary history and change of pro- with degree of evolutionary relationship. teins and their function. Such analysis is es- A typical phylogenetic analysis of protein sential to understanding major evolutionary sequence data involves five distinct steps: (a) questions, such as the origins and history of data collection, (b) inference of homology, (c) macromolecules, developmental mechanisms, sequence alignment, (d) alignment trimming, phenotypes, and life itself. -

New Syllabus

M.Sc. BIOINFORMATICS REGULATIONS AND SYLLABI (Effective from 2019-2020) Centre for Bioinformatics SCHOOL OF LIFE SCIENCES PONDICHERRY UNIVERSITY PUDUCHERRY 1 Pondicherry University School of Life Sciences Centre for Bioinformatics Master of Science in Bioinformatics The M.Sc Bioinformatics course started since 2007 under UGC Innovative program Program Objectives The main objective of the program is to train the students to learn an innovative and evolving field of bioinformatics with a multi-disciplinary approach. Hands-on sessions will be provided to train the students in both computer and experimental labs. Program Outcomes On completion of this program, students will be able to: Gain understanding of the principles and concepts of both biology along with computer science To use and describe bioinformatics data, information resource and also to use the software effectively from large databases To know how bioinformatics methods can be used to relate sequence to structure and function To develop problem-solving skills, new algorithms and analysis methods are learned to address a range of biological questions. 2 Eligibility for M.Sc. Bioinformatics Students from any of the below listed Bachelor degrees with minimum 55% of marks are eligible. Bachelor’s degree in any relevant area of Physics / Chemistry / Computer Science / Life Science with a minimum of 55% of marks 3 PONDICHERRY UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LIFE SCIENCES CENTRE FOR BIOINFORMATICS LIST OF HARD-CORE COURSES FOR M.Sc. BIOINFORMATICS (Academic Year 2019-2020 onwards) Course -

Molecular Phylogenetics Suggests a New Classification and Uncovers Convergent Evolution of Lithistid Demosponges

RESEARCH ARTICLE Deceptive Desmas: Molecular Phylogenetics Suggests a New Classification and Uncovers Convergent Evolution of Lithistid Demosponges Astrid Schuster1,2, Dirk Erpenbeck1,3, Andrzej Pisera4, John Hooper5,6, Monika Bryce5,7, Jane Fromont7, Gert Wo¨ rheide1,2,3* 1. Department of Earth- & Environmental Sciences, Palaeontology and Geobiology, Ludwig-Maximilians- Universita¨tMu¨nchen, Richard-Wagner Str. 10, 80333 Munich, Germany, 2. SNSB – Bavarian State Collections OPEN ACCESS of Palaeontology and Geology, Richard-Wagner Str. 10, 80333 Munich, Germany, 3. GeoBio-CenterLMU, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universita¨t Mu¨nchen, Richard-Wagner Str. 10, 80333 Munich, Germany, 4. Institute of Citation: Schuster A, Erpenbeck D, Pisera A, Paleobiology, Polish Academy of Sciences, ul. Twarda 51/55, 00-818 Warszawa, Poland, 5. Queensland Hooper J, Bryce M, et al. (2015) Deceptive Museum, PO Box 3300, South Brisbane, QLD 4101, Australia, 6. Eskitis Institute for Drug Discovery, Griffith Desmas: Molecular Phylogenetics Suggests a New Classification and Uncovers Convergent Evolution University, Nathan, QLD 4111, Australia, 7. Department of Aquatic Zoology, Western Australian Museum, of Lithistid Demosponges. PLoS ONE 10(1): Locked Bag 49, Welshpool DC, Western Australia, 6986, Australia e116038. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0116038 *[email protected] Editor: Mikhail V. Matz, University of Texas, United States of America Received: July 3, 2014 Accepted: November 30, 2014 Abstract Published: January 7, 2015 Reconciling the fossil record with molecular phylogenies to enhance the Copyright: ß 2015 Schuster et al. This is an understanding of animal evolution is a challenging task, especially for taxa with a open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which mostly poor fossil record, such as sponges (Porifera). -

Molecular Homology and Multiple-Sequence Alignment: an Analysis of Concepts and Practice

CSIRO PUBLISHING Australian Systematic Botany, 2015, 28, 46–62 LAS Johnson Review http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/SB15001 Molecular homology and multiple-sequence alignment: an analysis of concepts and practice David A. Morrison A,D, Matthew J. Morgan B and Scot A. Kelchner C ASystematic Biology, Uppsala University, Norbyvägen 18D, Uppsala 75236, Sweden. BCSIRO Ecosystem Sciences, GPO Box 1700, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia. CDepartment of Biology, Utah State University, 5305 Old Main Hill, Logan, UT 84322-5305, USA. DCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. Sequence alignment is just as much a part of phylogenetics as is tree building, although it is often viewed solely as a necessary tool to construct trees. However, alignment for the purpose of phylogenetic inference is primarily about homology, as it is the procedure that expresses homology relationships among the characters, rather than the historical relationships of the taxa. Molecular homology is rather vaguely defined and understood, despite its importance in the molecular age. Indeed, homology has rarely been evaluated with respect to nucleotide sequence alignments, in spite of the fact that nucleotides are the only data that directly represent genotype. All other molecular data represent phenotype, just as do morphology and anatomy. Thus, efforts to improve sequence alignment for phylogenetic purposes should involve a more refined use of the homology concept at a molecular level. To this end, we present examples of molecular-data levels at which homology might be considered, and arrange them in a hierarchy. The concept that we propose has many levels, which link directly to the developmental and morphological components of homology. -

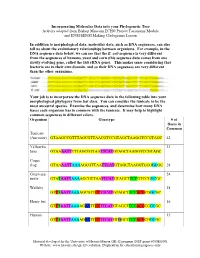

Incorporating Molecular Data Into Your Phylogenetic Tree Activity Adapted from Bishop Museum ECHO Project Taxonomy Module and ENSI/SENSI Making Cladograms Lesson

Incorporating Molecular Data into your Phylogenetic Tree Activity adapted from Bishop Museum ECHO Project Taxonomy Module and ENSI/SENSI Making Cladograms Lesson In addition to morphological data, molecular data, such as DNA sequences, can also tell us about the evolutionary relationships between organisms. For example, in the DNA sequence data below, we can see that the E. coli sequence is very different from the sequences of humans, yeast and corn (this sequence data comes from one slowly evolving gene, called the 16S rRNA gene). This makes sense considering that bacteria are in their own domain, and so their DNA sequences are very different than the other organisms. Your job is to incorporate the DNA sequence data in the following table into your morphological phylogeny from last class. You can consider the tunicate to be the most ancestral species. Examine the sequences, and determine how many DNA bases each organism has in common with the tunicate. It may help to highlight common sequences in different colors. Organism Genotype # of Bases in Common Tunicate (Ancestor) GTAAGCCGTTTAGCGTTAACGTCCGTAGCTAAGGTCCGTAGC 42 Yellowfin 33 tuna GTAAAATTTTTAGCGTTAATTCATGTAGCTAAGGTCCGTAGC Coqui frog GTAAAATTAAAAGCGTTAATTCATGTAGCTAAGGTCCGGCGC 28 Green sea 24 turtle GTATAATTAAAAGCGTTAATTCATGTAGCTTCCGTCCGGCGC Wallaby 18 GTTTAATTAAAAGCGTTCCTTCATGTAGCTTCCACGCGGCGC Hoary bat 16 GTTTAATTAAAAGATTTCCTTCATGTAGCTTCCACGCGGCGC Human 15 GTTTAATTAAAAGATTTCCTTCATGTGGCTTCCACGCGGCGC Material developed for the University of Hawaii-Manoa GK-12 program (NSF grant #05385500). Website: www.hawaii.edu/gk-12/evolution. Duplication for educational purposes only. Enter the number of bases each organism has in common with the tunicate into the phylogeny below: Tunicate Tuna Frog Turtle Wallaby Bat Human ____ bases ____ bases ____ bases ____ bases ____ bases ____ bases Does the molecular data agree with the morphological data? What would you do if the molecular and morphological data do not agree? Material developed for the University of Hawaii-Manoa GK-12 program (NSF grant #05385500). -

Molecular Phylogenetics: Principles and Practice

REVIEWS STUDY DESIGNS Molecular phylogenetics: principles and practice Ziheng Yang1,2 and Bruce Rannala1,3 Abstract | Phylogenies are important for addressing various biological questions such as relationships among species or genes, the origin and spread of viral infection and the demographic changes and migration patterns of species. The advancement of sequencing technologies has taken phylogenetic analysis to a new height. Phylogenies have permeated nearly every branch of biology, and the plethora of phylogenetic methods and software packages that are now available may seem daunting to an experimental biologist. Here, we review the major methods of phylogenetic analysis, including parsimony, distance, likelihood and Bayesian methods. We discuss their strengths and weaknesses and provide guidance for their use. statistical Systematics Before the advent of DNA sequencing technologies, phylogenetics, creating the emerging field of 2,18,19 The inference of phylogenetic phylogenetic trees were used almost exclusively to phylogeography. In species tree methods , the gene relationships among species describe relationships among species in systematics and trees at individual loci may not be of direct interest and and the use of such information taxonomy. Today, phylogenies are used in almost every may be in conflict with the species tree. By averaging to classify species. branch of biology. Besides representing the relation- over the unobserved gene trees under the multi-species 20 Taxonomy ships among species on the tree of life, phylogenies -

Molecular Phylogenetics: State-Of-The- Art Methods for Looking Into the Past

262 Review TRENDS in Genetics Vol.17 No.5 May 2001 Molecular phylogenetics: state-of-the- art methods for looking into the past Simon Whelan, Pietro Liò and Nick Goldman As the amount of molecular sequence data in the public domain grows, so occurrence at each sequence site is mathematically does the range of biological topics that it influences through evolutionary modelled by a MARKOV PROCESS. Typically, the same considerations. In recent years, a number of developments have enabled Markov process model is applied to each sequence molecular phylogenetic methodology to keep pace. Likelihood-based inferential site. Different models are distinguished by their techniques, although controversial in the past, lie at the heart of these new assumptions or PARAMETERIZATIONS regarding the methods and are producing the promised advances in the understanding of average rates of occurrence of all the possible sequence evolution. They allow both a wide variety of phylogenetic inferences replacements3. It is now well established that from sequence data and robust statistical assessment of all results. It cannot more complex models, often describing replacement remain acceptable to use outdated data analysis techniques when superior rates in terms of a variety of biological phenomena, alternatives exist. Here, we discuss the most important and exciting methods generally give a statistically better fit to observed currently available to the molecular phylogeneticist. patterns of sequence evolution4–9, giving more accurate and robust estimates both of phylogeny10–12 Only through MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETIC (see Glossary) and the statistical confidence in the phylogeny13. The studies can we understand fully the rapidly development of more accurate models of sequence accumulating genomic sequence data and evolution has been a particularly active and fertile information regarding proteins’ structure and area of research in recent years, in the expectation function. -

Annonex2embl: Automatic Preparation of Annotated DNA Sequences for Bulk Submissions to ENA Michael Gruenstaeudl1

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/820480; this version posted October 28, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. annonex2embl: automatic preparation of annotated DNA sequences for bulk submissions to ENA Michael Gruenstaeudl1 1Institut f ¨urBiologie, Freie Universitat¨ Berlin, 14195 Berlin, Germany Email address: [email protected] ABSTRACT Motivation: The submission of annotated sequence data to public sequence databases constitutes a central pillar in biological research. The surge of novel DNA sequences awaiting database submission due to the application of next-generation sequencing has increased the need for software tools that facilitate bulk submissions. This need has yet to be met with a concurrent development of tools to automate the preparatory work preceding such submissions. Results: I introduce annonex2embl, a Python package that automates the preparation of complete sequence flatfiles for large-scale sequence submissions to the European Nucleotide Archive. The tool enables the conversion of DNA sequence alignments that are co-supplied with sequence annotations and metadata to submission-ready flatfiles. Among other features, the software automatically accounts for length differences among the input sequences while maintaining correct annotations, automatically interlaces metadata to each record, and displays a design suitable for easy integration into bioinformatic workflows. As proof of its utility, annonex2embl is employed in preparing a dataset of more than 1,500 fungal DNA sequences for database submission. -

Inferring Biological Networks from Genome-Wide Transcriptional And

INFERRING BIOLOGICAL NETWORKS FROM GENOME-WIDE TRANSCRIPTIONAL AND FITNESS DATA By WAZEER MOHAMMAD VARSALLY A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy College of Life and Environmental Sciences School of Biosciences The University of Birmingham July 2013 I University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT In the last 15 years, the increased use of high throughput biology techniques such as genome-wide gene expression profiling, fitness profiling and protein interactomics has led to the generation of an extraordinary amount of data. The abundance of such diverse data has proven to be an essential foundation for understanding the complexities of molecular mechanisms and underlying pathways within a biological system. One approach of extrapolating biological information from this wealth of data has been through the use of reverse engineering methods to infer biological networks. This thesis demonstrates the capabilities and applications of such methodologies in identifying functionally enriched network modules in the yeast species Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe. This study marks the first time a mutual information based network inference approach has been applied to a set of specific genome-wide expression and fitness compendia, as well as the integration of these multi- level compendia. -

Molecular Phylogenetics Next Two Lectures

Next two lectures: • What is a phylogenetic tree? • How are trees inferred using molecular data? Molecular phylogenetics • How do you assess confidence in trees and clades on trees? Michael Worobey • Why do trees for different data sets sometimes conflict? • What can you do with trees beyond simply inferring relatedness? Molecular phylogenetics fundamentals Tree terminology All of life is related by common ancestry. Recovering this pattern, the "Tree of Life", is one of the primary goals of evolutionary biology. Even at the A tree is a mathematical structure which is used to model the actual evolutionary population level, the phylogenetic tree is indispensable as a tool for estimating history of a group of sequences or organisms. This actual pattern of historical parameters of interest. Likewise at the among species level, it is relationships is the phylogeny or evolutionary tree which we try and indispensable for examining patterns of diversification over time. First, you estimate. A tree consists of nodes connected by branches (also called need to be familiar with some tree terminology. edges). Terminal nodes (also called leaves, OTUs [Operational Taxonomic Units], external nodes or terminal taxa) represent sequences or organisms for which we have data; they may be either extant or extinct. Phylogenetics interlude Phylogenetics interlude • It’s all about ancestor and All the phylogenetics offspring populations, • Mutations happen when you need to know, in lineages branching genetic material is copied 5 minutes… • The ancestor could