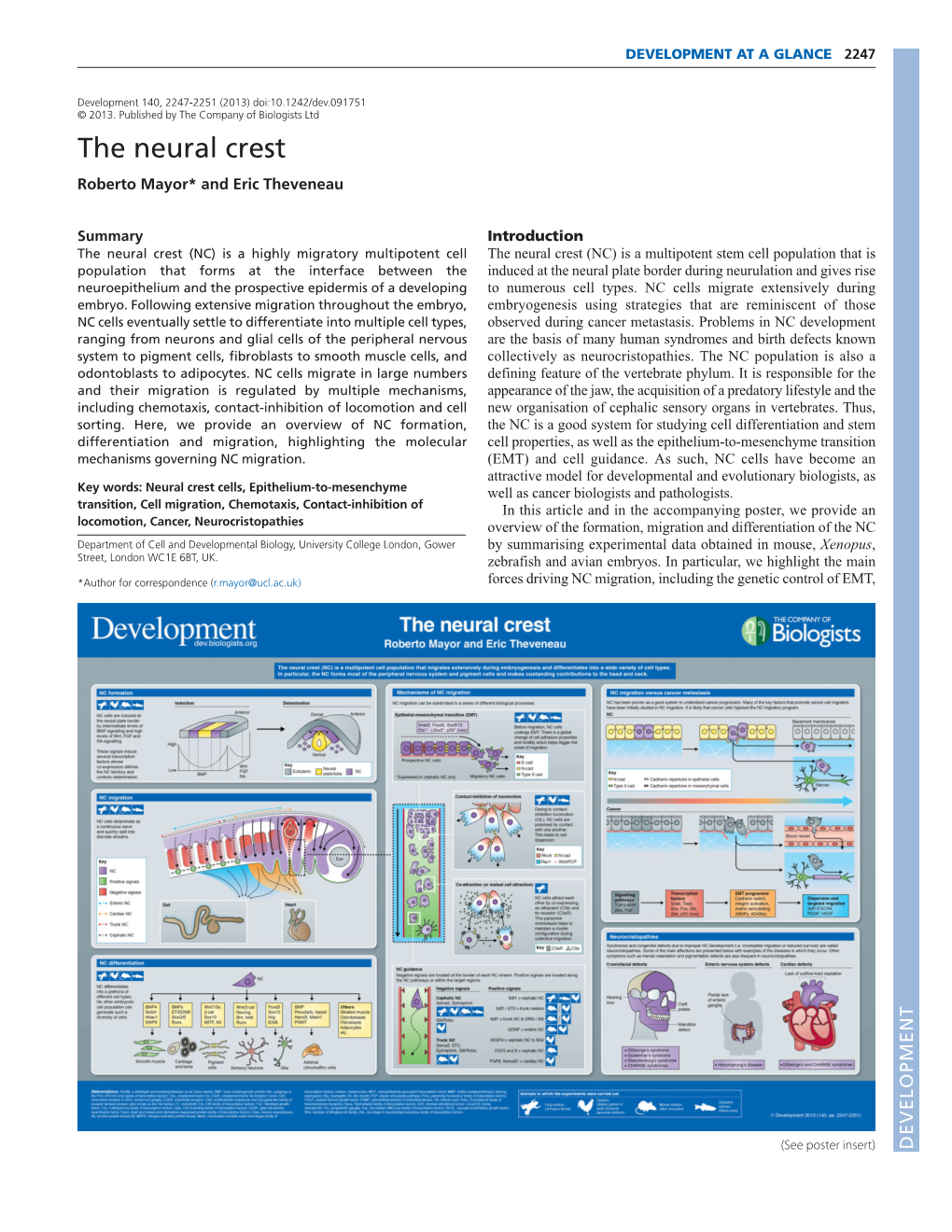

The Neural Crest Roberto Mayor* and Eric Theveneau

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notch Signaling Regulates the Differentiation of Neural Crest From

ß 2014. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Cell Science (2014) 127, 2083–2094 doi:10.1242/jcs.145755 RESEARCH ARTICLE Notch signaling regulates the differentiation of neural crest from human pluripotent stem cells Parinya Noisa1,2, Carina Lund2, Kartiek Kanduri3, Riikka Lund3, Harri La¨hdesma¨ki3, Riitta Lahesmaa3, Karolina Lundin2, Hataiwan Chokechuwattanalert2, Timo Otonkoski4,5, Timo Tuuri5,6,* and Taneli Raivio2,4,*,` ABSTRACT Kokta et al., 2013). Neural crest cells originate from neuroectoderm at the border between the neural plate and the Neural crest cells are specified at the border between the neural epiderm (Meulemans and Bronner-Fraser, 2004), and they are plate and the epiderm. They are capable of differentiating into marked by the expression of genes that are specific for the neural- various somatic cell types, including craniofacial and peripheral plate border, such as DLX5, MSX1, MSX2 and ZIC1. Later, during nerve tissues. Notch signaling plays important roles during the neural-tube folding process, neural crest cells remain within neurogenesis; however, its function during human neural crest the neural folds and subsequently localize inside the dorsal development is poorly understood. Here, we generated self- portion of the neural tube. These premigratory neural crest cells renewing premigratory neural-crest-like cells (pNCCs) from human express specifier genes, such as SNAIL (also known as SNAI1), pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) and investigated the roles of Notch SLUG (also known as SNAI2), SOX10 and TWIST1 (LaBonne and signaling during neural crest differentiation. pNCCs expressed Bronner-Fraser, 2000; Mancilla and Mayor, 1996). Following the various neural-crest-specifier genes, including SLUG (also known formation of the neural tube, premigratory neural crest cells as SNAI2), SOX10 and TWIST1, and were able to differentiate into undergo an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and most neural crest derivatives. -

The Migration of Neural Crest Cells and the Growth of Motor Axons Through the Rostral Half of the Chick Somite

/. Embryol. exp. Morph. 90, 437-455 (1985) 437 Printed in Great Britain © The Company of Biologists Limited 1985 The migration of neural crest cells and the growth of motor axons through the rostral half of the chick somite M. RICKMANN, J. W. FAWCETT The Salk Institute and The Clayton Foundation for Research, California division, P.O. Box 85800, San Diego, CA 92138, U.S.A. AND R. J. KEYNES Department of Anatomy, University of Cambridge, Downing St, Cambridge, CB2 3DY, U.K. SUMMARY We have studied the pathway of migration of neural crest cells through the somites of the developing chick embryo, using the monoclonal antibodies NC-1 and HNK-1 to stain them. Crest cells, as they migrate ventrally from the dorsal aspect of the neural tube, pass through the lateral part of the sclerotome, but only through that part of the sclerotome which lies in the rostral half of each somite. This migration pathway is almost identical to the path which pre- sumptive motor axons take when they grow out from the neural tube shortly after the onset of neural crest migration. In order to see whether the ventral root axons are guided along this pathway by neural crest cells, we surgically excised the neural crest from a series of embryos, and examined the pattern of axon outgrowth approximately 24 h later. In somites which contained no neural crest cells, ventral root axons were still found only in the rostral half of the somite, although axonal growth was slightly delayed. These axons were surrounded by sheath cells, which had presumably migrated out of the neural tube, to a point about 50 jan proximal to the growth cones. -

Works Neuroembryology

Swarthmore College Works Biology Faculty Works Biology 1-1-2017 Neuroembryology D. Darnell Scott F. Gilbert Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-biology Part of the Biology Commons Let us know how access to these works benefits ouy Recommended Citation D. Darnell and Scott F. Gilbert. (2017). "Neuroembryology". Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Developmental Biology. Volume 6, Issue 1. DOI: 10.1002/wdev.215 https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-biology/493 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biology Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Wiley Interdiscip Manuscript Author Rev Dev Manuscript Author Biol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2018 January 01. Published in final edited form as: Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol. 2017 January ; 6(1): . doi:10.1002/wdev.215. Neuroembryology Diana Darnell1 and Scott F. Gilbert2 1University of Arizona College of Medicine 2Swarthmore College and University of Helsinki Abstract How is it that some cells become neurons? And how is it that neurons become organized in the spinal cord and brain to allow us to walk and talk, to see, recall events in our lives, feel pain, keep our balance, and think? The cells that are specified to form the brain and spinal cord are originally located on the outside surface of the embryo. They loop inward to form the neural tube in a process called neurulation. -

The Genetic Basis of Mammalian Neurulation

REVIEWS THE GENETIC BASIS OF MAMMALIAN NEURULATION Andrew J. Copp*, Nicholas D. E. Greene* and Jennifer N. Murdoch‡ More than 80 mutant mouse genes disrupt neurulation and allow an in-depth analysis of the underlying developmental mechanisms. Although many of the genetic mutants have been studied in only rudimentary detail, several molecular pathways can already be identified as crucial for normal neurulation. These include the planar cell-polarity pathway, which is required for the initiation of neural tube closure, and the sonic hedgehog signalling pathway that regulates neural plate bending. Mutant mice also offer an opportunity to unravel the mechanisms by which folic acid prevents neural tube defects, and to develop new therapies for folate-resistant defects. 6 ECTODERM Neurulation is a fundamental event of embryogenesis distinct locations in the brain and spinal cord .By The outer of the three that culminates in the formation of the neural tube, contrast, the mechanisms that underlie the forma- embryonic (germ) layers that which is the precursor of the brain and spinal cord. A tion, elevation and fusion of the neural folds have gives rise to the entire central region of specialized dorsal ECTODERM, the neural plate, remained elusive. nervous system, plus other organs and embryonic develops bilateral neural folds at its junction with sur- An opportunity has now arisen for an incisive analy- structures. face (non-neural) ectoderm. These folds elevate, come sis of neurulation mechanisms using the growing battery into contact (appose) in the midline and fuse to create of genetically targeted and other mutant mouse strains NEURAL CREST the neural tube, which, thereafter, becomes covered by in which NTDs form part of the mutant phenotype7.At A migratory cell population that future epidermal ectoderm. -

Semaphorin3a/Neuropilin-1 Signaling Acts As a Molecular Switch Regulating Neural Crest Migration During Cornea Development

Developmental Biology 336 (2009) 257–265 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Developmental Biology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/developmentalbiology Semaphorin3A/neuropilin-1 signaling acts as a molecular switch regulating neural crest migration during cornea development Peter Y. Lwigale a,⁎, Marianne Bronner-Fraser b a Department of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, MS 140, Rice University, P.O. Box 1892, Houston, TX 77251, USA b Division of Biology, 139-74, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA article info abstract Article history: Cranial neural crest cells migrate into the periocular region and later contribute to various ocular tissues Received for publication 2 April 2009 including the cornea, ciliary body and iris. After reaching the eye, they initially pause before migrating over Revised 11 September 2009 the lens to form the cornea. Interestingly, removal of the lens leads to premature invasion and abnormal Accepted 6 October 2009 differentiation of the cornea. In exploring the molecular mechanisms underlying this effect, we find that Available online 13 October 2009 semaphorin3A (Sema3A) is expressed in the lens placode and epithelium continuously throughout eye development. Interestingly, neuropilin-1 (Npn-1) is expressed by periocular neural crest but down- Keywords: Semaphorin3A regulated, in a manner independent of the lens, by the subpopulation that migrates into the eye and gives Neuropilin-1 rise to the cornea endothelium and stroma. In contrast, Npn-1 expressing neural crest cells remain in the Neural crest periocular region and contribute to the anterior uvea and ocular blood vessels. Introduction of a peptide that Cornea inhibits Sema3A/Npn-1 signaling results in premature entry of neural crest cells over the lens that Lens phenocopies lens ablation. -

Homocysteine Intensifies Embryonic LIM3 Expression in Migratory Neural Crest Cells: a Quantitative Confocal Microscope Study

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Dissertations and Theses @ UNI Student Work 2014 Homocysteine intensifies embryonic LIM3 expression in migratory neural crest cells: A quantitative confocal microscope study Jordan Naumann University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©2014 Jordan Naumann Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Naumann, Jordan, "Homocysteine intensifies embryonic LIM3 expression in migratory neural crest cells: A quantitative confocal microscope study" (2014). Dissertations and Theses @ UNI. 89. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd/89 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses @ UNI by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright by JORDAN NAUMANN 2014 All Rights Reserved HOMOCYSTEINE INTENSIFIES EMBRYONIC LIM3 EXPRESSION IN MIGRATORY NEURAL CREST CELLS – A QUANTITATIVE CONFOCAL MICROSCOPE STUDY An Abstract of a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Jordan Naumann University of Northern Iowa May 2014 ABSTRACT Elevated levels of homocysteine in maternal blood and amniotic fluid are associated with cardiovascular, renal, skeletal, and endocrine diseases and also with embryonic malformations related to neural crest cells. Neural crest cells are necessary for the formation of tissues and organs throughout the body of vertebrate animals. The migration of neural crest cells is essential for proper development of the target tissues. When migration is disrupted, abnormalities may occur. -

Fate of the Mammalian Cardiac Neural Crest

Development 127, 1607-1616 (2000) 1607 Printed in Great Britain © The Company of Biologists Limited 2000 DEV4300 Fate of the mammalian cardiac neural crest Xiaobing Jiang1,3, David H. Rowitch4,*, Philippe Soriano5, Andrew P. McMahon4 and Henry M. Sucov2,3,‡ Departments of 1Biological Sciences and 2Cell & Neurobiology, 3Institute for Genetic Medicine, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, 2250 Alcazar St., IGM 240, Los Angeles, CA 90033, USA 4Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, Harvard University, 16 Divinity Ave., Cambridge, MA 02138, USA 5Program in Developmental Biology, Division of Basic Sciences, A2-025, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, 1100 Fairview Avenue North, PO Box 19024, Seattle, WA 98109, USA *Present address: Department of Pediatric Oncology, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, 44 Binney St., Boston, MA 02115, USA ‡Author for correspondence (e-mail: [email protected]) Accepted 26 January; published on WWW 21 March 2000 SUMMARY A subpopulation of neural crest termed the cardiac neural of these vessels. Labeled cells populate the crest is required in avian embryos to initiate reorganization aorticopulmonary septum and conotruncal cushions prior of the outflow tract of the developing cardiovascular to and during overt septation of the outflow tract, and system. In mammalian embryos, it has not been previously surround the thymus and thyroid as these organs form. experimentally possible to study the long-term fate of this Neural-crest-derived mesenchymal cells are abundantly population, although there is strong inference that a similar distributed in midgestation (E9.5-12.5), and adult population exists and is perturbed in a number of genetic derivatives of the third, fourth and sixth pharyngeal arch and teratogenic contexts. -

NERVOUS SYSTEM هذا الملف لالستزادة واثراء المعلومات Neuropsychiatry Block

NERVOUS SYSTEM هذا الملف لﻻستزادة واثراء المعلومات Neuropsychiatry block. قال تعالى: ) َو َل َق د َخ َل قنَا ا ِْلن َسا َن ِمن ُس ََل َل ة ِ من ِطي ن }12{ ثُ م َجعَ لنَاه ُ نُ ط َفة فِي َق َرا ر م ِكي ن }13{ ثُ م َخ َل قنَا ال ُّن ط َفة َ َع َل َقة َف َخ َل قنَا ا لعَ َل َقة َ ُم ضغَة َف َخ َل قنَا ا ل ُم ضغَة َ ِع َظا ما َف َك َس ونَا ا ل ِع َظا َم َل ح ما ثُ م أَن َشأنَاه ُ َخ ل قا آ َخ َر َفتَبَا َر َك ّللا ُ أَ ح َس ُن ا ل َخا ِل ِقي َن }14{( Resources BRS Embryology Book. Pathoma Book ( IN DEVELOPMENTAL ANOMALIES PART ). [email protected] 1 OVERVIEW A- Central nervous system (CNS) is formed in week 3 of development, during which time the neural plate develops. The neural plate, consisting of neuroectoderm, becomes the neural tube, which gives rise to the brain and spinal cord. B- Peripheral nervous system (PNS) is derived from three sources: 1. Neural crest cells 2. Neural tube, which gives rise to all preganglionic autonomic nerves (sympathetic and parasympathetic) and all nerves (-motoneurons and -motoneurons) that innervate skeletal muscles 3. Mesoderm, which gives rise to the dura mater and to connective tissue investments of peripheral nerve fibers (endoneurium, perineurium, and epineurium) DEVELOPMENT OF THE NEURAL TUBE Neurulation refers to the formation and closure of the neural tube. BMP-4 (bone morphogenetic protein), noggin (an inductor protein), chordin (an inductor protein), FGF-8 (fibroblast growth factor), and N-CAM (neural cell adhesion molecule) appear to play a role in neurulation. -

Understanding Paraxial Mesoderm Development and Sclerotome Specification for Skeletal Repair Shoichiro Tani 1,2, Ung-Il Chung2,3, Shinsuke Ohba4 and Hironori Hojo2,3

Tani et al. Experimental & Molecular Medicine (2020) 52:1166–1177 https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-020-0482-1 Experimental & Molecular Medicine REVIEW ARTICLE Open Access Understanding paraxial mesoderm development and sclerotome specification for skeletal repair Shoichiro Tani 1,2, Ung-il Chung2,3, Shinsuke Ohba4 and Hironori Hojo2,3 Abstract Pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) are attractive regenerative therapy tools for skeletal tissues. However, a deep understanding of skeletal development is required in order to model this development with PSCs, and for the application of PSCs in clinical settings. Skeletal tissues originate from three types of cell populations: the paraxial mesoderm, lateral plate mesoderm, and neural crest. The paraxial mesoderm gives rise to the sclerotome mainly through somitogenesis. In this process, key developmental processes, including initiation of the segmentation clock, formation of the determination front, and the mesenchymal–epithelial transition, are sequentially coordinated. The sclerotome further forms vertebral columns and contributes to various other tissues, such as tendons, vessels (including the dorsal aorta), and even meninges. To understand the molecular mechanisms underlying these developmental processes, extensive studies have been conducted. These studies have demonstrated that a gradient of activities involving multiple signaling pathways specify the embryonic axis and induce cell-type-specific master transcription factors in a spatiotemporal manner. Moreover, applying the knowledge of mesoderm development, researchers have attempted to recapitulate the in vivo development processes in in vitro settings, using mouse and human PSCs. In this review, we summarize the state-of-the-art understanding of mesoderm development and in vitro modeling of mesoderm development using PSCs. We also discuss future perspectives on the use of PSCs to generate skeletal tissues for basic research and clinical applications. -

Hox Genes Make the Connection

Downloaded from genesdev.cshlp.org on September 26, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press PERSPECTIVE Establishing neuronal circuitry: Hox genes make the connection James Briscoe1 and David G. Wilkinson2 Developmental Neurobiology, National Institute for Medical Research, Mill Hill, London, NW7 1AA, UK The vertebrate nervous system is composed of a vast meres maintain these partitions. Each rhombomere array of neuronal circuits that perceive, process, and con- adopts unique cellular and molecular properties that ap- trol responses to external and internal cues. Many of pear to underlie the spatial organization of the genera- these circuits are established during embryonic develop- tion of cranial motor nerves and neural crest cells. More- ment when axon trajectories are initially elaborated and over, the coordination of positional identity between the functional connections established between neurons and central and peripheral derivatives of the hindbrain may their targets. The assembly of these circuits requires ap- underlie the anatomical and functional registration be- propriate matching between neurons and the targets tween MNs, cranial ganglia, and the routes of neural they innervate. This is particularly apparent in the case crest migration. Cranial neural crest cells derived from of the innervation of peripheral targets by central ner- the dorsal hindbrain migrate ventral-laterally as discrete vous system neurons where the development of the two streams adjacent to r2, r4, and r6 to populate the first tissues must be coordinated to establish and maintain three branchial arches (BA1–BA3), respectively, where circuits. A striking example of this occurs during the they generate distinct skeletal and connective tissue formation of the vertebrate head. -

Mechanisms of Neurulation: Traditional Viewpoint and Recent Advances

Development 109, 243-270 (L990) Review Article 243 Printed in Great Britain ©The Company of Biologists Limited 1990 Mechanisms of neurulation: traditional viewpoint and recent advances GARY C. SCHOENWOLF* and JODI L. SMITH Department of Anatomy, University of Utah, School of Medicine, Salt Lake City, Utah 84132, USA * Author for correspondence Introduction 243 Traditional viewpoint 248 The three fundamentals of the traditional viewpoint 248 Contemporary viewpoint 248 Regional differences in neural plate shaping and bending 248 Contemporary viewpoint: First fundamental 252 Traditional disregard for extrinsic forces in neurulation 252 Evidence of intrinsic forces in neural plate shaping and extrinsic forces in bending 254 Contemporary viewpoint: Second fundamental 254 Role of neurepithelial cell elongation in neural plate shaping 255 Roles of other form-shaping events in neural plate shaping 255 Cell rearrangement 255 Cell division 256 Role of neurepithelial cell wedging in neural plate bending 257 MHP cell wedging: an active event 259 MHP cell wedging and neural plate furrowing 259 Roles of other form-shaping events in neural plate bending 260 Longitudinal stretching 260 Hinge point formation 262 Expansion of deep tissues 263 Contemporary viewpoint: Third fundamental 264 Role of microtubules in neurepithelial cell elongation 264 Role of apical microfilament bands in neurepithelial cell wedging 264 Role of cell cycle alteration and basal expansion in neurepithelial cell wedging 265 Conclusions 267 Summary In this review article, the traditional -

Specification and Formation of the Neural Crest: Perspectives on Lineage Segregation

Received: 3 November 2018 Revised: 17 December 2018 Accepted: 18 December 2018 DOI: 10.1002/dvg.23276 REVIEW Specification and formation of the neural crest: Perspectives on lineage segregation Maneeshi S. Prasad1 | Rebekah M. Charney1 | Martín I. García-Castro Division of Biomedical Sciences, School of Medicine, University of California, Riverside, Summary California The neural crest is a fascinating embryonic population unique to vertebrates that is endowed Correspondence with remarkable differentiation capacity. Thought to originate from ectodermal tissue, neural Martín I. García-Castro, Division of Biomedical crest cells generate neurons and glia of the peripheral nervous system, and melanocytes Sciences, School of Medicine, University of California, Riverside, CA. throughout the body. However, the neural crest also generates many ectomesenchymal deriva- Email: [email protected] tives in the cranial region, including cell types considered to be of mesodermal origin such as Funding information cartilage, bone, and adipose tissue. These ectomesenchymal derivatives play a critical role in the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial formation of the vertebrate head, and are thought to be a key attribute at the center of verte- Research, Grant/Award Numbers: brate evolution and diversity. Further, aberrant neural crest cell development and differentiation R01DE017914, F32DE027862 is the root cause of many human pathologies, including cancers, rare syndromes, and birth mal- formations. In this review, we discuss the current