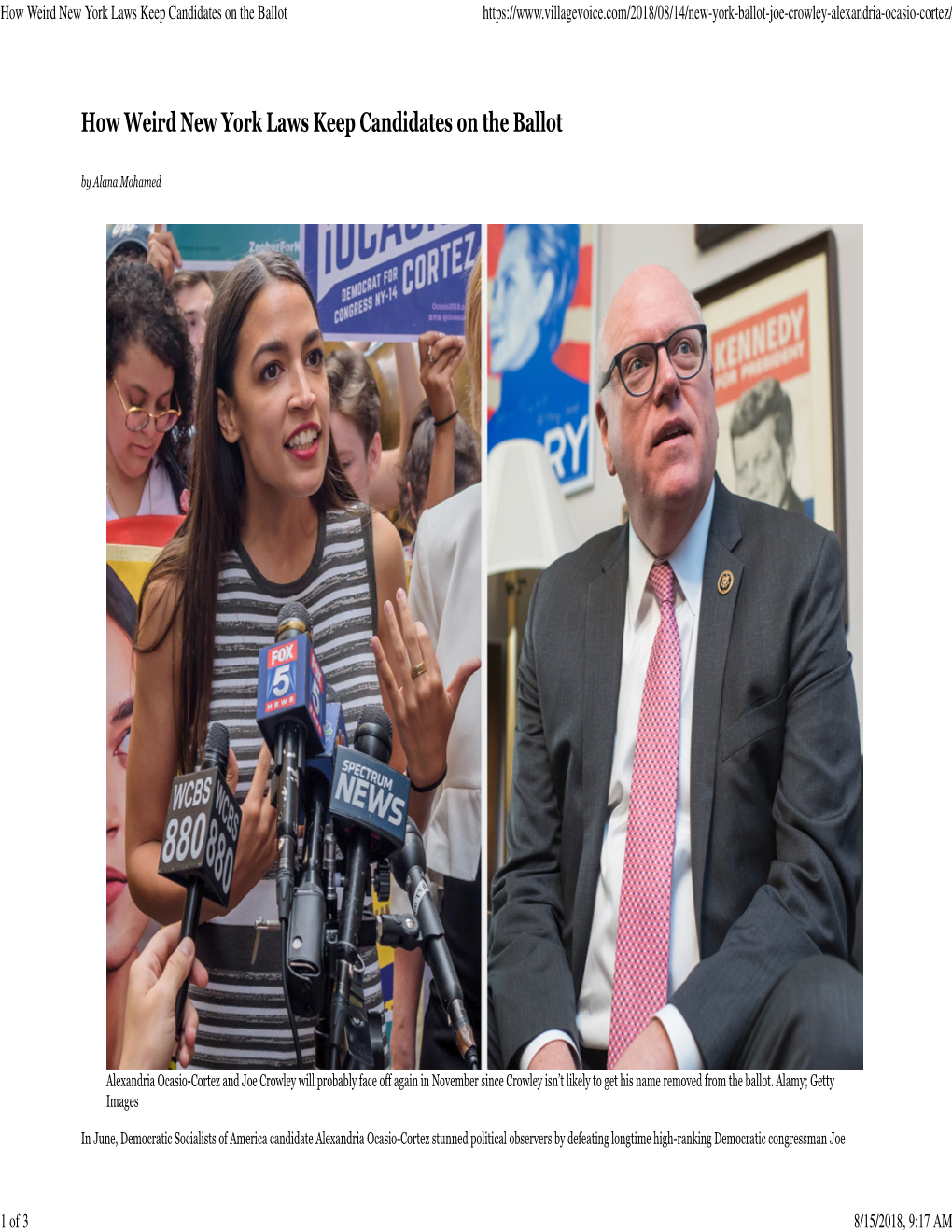

How Weird New York Laws Keep Candidates on the Ballot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United States District Court Southern District of New

Case 1:10-cv-06923-JSR Document 18 Filed 09/30/10 Page 1 of 3 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK -------------------------------------------------------------X CONSERVATIVE PARTY OF NEW YORK STATE and WORKING FAMILIES PARTY, 10 CIV 6923 (JSR) ECF Case Plaintiffs, MOTION OF THE CITY -against- ORGANIZATIONS OF THE NEW YORK INDEPENDENCE NEW YORK STATE BOARD OF ELECTIONS; PARTY FOR LEAVE TO JAMES A. WALSH, DOUGLAS A. KELLNER, BRIEF AS AMICI CURIAE EVELYN J. AQUILA, and GREGORY P. PETERSON, in their official capacities as Commissioners of the New York State Board of Elections; TODD D. VALENTINE and ROBERT A. BREHM, in their official capacities as Co-Executive Directors of the New York State Board of Elections Defendants. -------------------------------------------------------------X The City Organizations of the New York Independence Party respectfully move for leave to file the Proposed Memorandum of Law of Amici Curiae, annexed hereto as Exhibit A. Annexed hereto as Exhibit B is the declaration of Cathy L. Stewart in support of this motion, and annexed hereto at Exhibit C is a Proposed Order. The City Organizations of the New York Independence Party are interested in this litigation for the reasons set forth in the declaration of Cathy L. Stewart annexed as Exhibit B. The City Organizations of the New York Independence Party respectfully seek leave to file an amici curiae brief in order to provide perspective from the vantage point of the Independence Party organizations of New York City and their members on the impact of New York Election Law Sec. 9-112(4) in light of the decision of defendants on how to treat over voting on the new optical scan voting system. -

With Unions in Decline, Trump's Path to the Presidency Is Unlikely to Be

With unions in decline, Trump’s path to the presidency is unlikely to be through the Rust Belt. blogs.lse.ac.uk/usappblog/2016/08/10/with-unions-in-decline-trumps-path-to-the-presidency-is-unlikely-to-be-through-the-rust-belt/ In this election, Donald Trump has been drawing a great deal of his support from disaffected white working-class voters. Michael McQuarrie writes that Trump’s strategy of courting this group is not surprising; white workers have been slipping away from the Democratic Party for nearly 50 years. Much of this is down to the decline of unions, which in the past had been able to keep white voters anchored to the left. This decline – along with the changing demographics of the Rust Belt- also hurts Trump’s electoral chances; without unions to mobilize them, working class whites are less likely to vote. Donald Trump’s campaign manager, Paul Manafort, has argued that Trump’s path to the Presidency was open because of his ability to win traditionally democratic Rust Belt states. Trump’s super PACs, however, are only targeting the Rust Belt states of Pennsylvania and Ohio, along with Florida. This is an extremely narrow map, but one that nonetheless has become something like the common sense of this election cycle. Trump, the argument goes, appeals to uneducated white workers more than any other group. To win, he needs to capture swing states with lots of disaffected white working-class voters. The Democrats are not particularly interested in fighting for these votes. Hillary Clinton’s acceptance speech at the Democratic convention, which seemed to have a word for each part of the Democratic coalition, could only appeal to white workers by mustering a comment on Trump’s hypocrisy (Trump ties are made in China, not Colorado!), a ploy that worked with patrician Mitt Romney in 2012, but is unlikely to work with the new tribune of the white workers. -

Jen Metzger Receives Working Families Party Endorsement in State Senate Race

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE April 16, 2018 CONTACT: Kelleigh McKenzie, 845-518-7352 [email protected] Jen Metzger Receives Working Families Party Endorsement in State Senate Race ROSENDALE, NY — The Working Families Party officially endorsed Rosendale Town Councilwoman Jen Metzger today in her campaign to be the next state senator for New York’s 42nd District. “I am honored to receive this endorsement,” said Metzger. “The Working Families Party stands for an economy that works for everyone, and a democracy in which every voice matters. I am proud to stand with them.” Phillip Leber, Hudson Region Political Director of the Working Families Party, said, “Jen Metzger proves that you don’t need to make a false choice between principled, progressive values, and winning elections. Social movements can only do their jobs if we elect authentic progressives, and Jen Metzger is the real deal.” The endorsement is the outcome of a rigorous application and interview process by the Hudson Regional Council of the Working Families Party, which consists of members of the Hudson Valley Area Labor Federation AFL-CIO, the New York Public Employees Federation, the New York State Nurses Association, New York State United Teachers, Communication Workers of America, Community Voices Heard Power, Hudson Valley Progressives, Citizen Action of New York, and state committee members of the Working Families Party itself. “For two decades now, our state senator has made a career out of taking money from corporate donors and polluters, while giving us handouts,” said Metzger. “I look forward to Friends of Jen Metzger, PO Box 224, Rosendale NY 12472 ⭑ [email protected] partnering with the Working Families Party to support—not block—legislation that meaningfully improves the lives of the people in our district.” Jen Metzger’s campaign website is jenmetzger.com, and voters can also find her on social media at Facebook.com/jenmetzgerNY and Twitter.com/jenmetzgerNY. -

Populism and Politics: William Alfred Peffer and the People's Party

University of Kentucky UKnowledge American Politics Political Science 1974 Populism and Politics: William Alfred Peffer and the People's Party Peter H. Argersinger University of Maryland Baltimore County Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Argersinger, Peter H., "Populism and Politics: William Alfred Peffer and the People's Party" (1974). American Politics. 8. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_political_science_american_politics/8 POPULISM and POLITICS This page intentionally left blank Peter H. Argersinger POPULISM and POLITICS William Alfred Peffer and the People's Party The University Press of Kentucky ISBN: 978-0-8131-5108-3 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 73-86400 Copyright © 1974 by The University Press of Kentucky A statewide cooperative scholarly publishing agency serving Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky State College, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University- Editorial and Sales Offices: Lexington, Kentucky -

I Thank You for the Opportunity You Gave Me in Your Issue of the 3Rd Inst. to Present to the Populists of North Carolina My View

Mr. Kestler Again. [The Progressive Farmer, March 24, 1896] He Reples [sic] to Mr. Green and Quotes Other Authorities. Correspondence of the Progressive Farmer. I thank you for the opportunity you gave me in your issue of the 3rd inst. to present to the Populists of North Carolina my views on the political situation, and as you were so kind as to give my good friend, Mr. Green, space to reply to me, I will again ask you for space to more fully establish my position and to controvert my friend’s arguments. My aim in this matter is to carry our banner to victory in November, and no one has yet denied but what my proposed plan would do it, and every one has admitted that Mr. Butler’s and Mr. Green’s plan would cause us defeat. My impression was that we wanted to win; that there was a goal ahead for us to reach, and I was working towards that end. My opponent doesn’t seem to care whether we win or lose; and “All’s well that ends well.” Now, as to that article. My friend sees a seeming contradiction between the statements that I said the people were with me, and that “I felt like one who treads alone,” etc. Such is not the case. In the latter statement I was telling the effect Mr. Butler’s plan would have upon our party, and I called upon all not to heed his advice, but to stick to their party and to their principles. To disconnect any article is hardly fair; you destroy the meaning. -

Reputational Effects in Legislative Elections: Measuring the Impact of Repeat Candidacy and Interest Group Endorsements

REPUTATIONAL EFFECTS IN LEGISLATIVE ELECTIONS: MEASURING THE IMPACT OF REPEAT CANDIDACY AND INTEREST GROUP ENDORSEMENTS A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by James Brendan Kelley December 2018 Examining Committee Members: Robin Kolodny, Advisory Chair, Political Science Ryan J. Vander Wielen, Examination Chair, Political Science Kevin Arceneaux, Political Science Joshua Klugman, Sociology and Psychology ABSTRACT This dissertation consists of three projects related to reputational effects in legislative elections. Building on the candidate emergence, repeat candidates and congressional donor literatures, these articles use novel datasets to further our understanding of repeat candidacy and the impact of interest group endorsements on candidate contributions. The first project examines the conditions under which losing state legislative candidates will appear on the successive general election ballot. Broadly speaking, I find a good deal of support for the notion that candidates respond rationally to changes in their political environment when determining whether to run again. The second project aims to measure the impact of repeat candidacy on state legislative election outcomes. Ultimately I find a reward/penalty structure through which losing candidates for lower chamber seats that perform well in their first election have a slight advantage over first- time candidates in their repeat elections. The final chapter of this dissertation examines the relationship between interest group endorsements and individual contributions for 2010 U.S. Senate candidates. The results of this chapter suggest that some interest group endorsements lead to increased campaign contributions, as compared to unendorsed candidates, but that others do not. -

Title of Article

Title of Article T H E S E C R E T TO HIS SUCCESS? PA G E 3 R E D E F I N I N G REDISTRICTING PA G E 7 EYE ON KATRINA PA G E 3 1 CAPTION TO COME PA G E 4 0 $6.95 SPRING 2006 THE NEO-INDEPENDENT I SPRING 2006 Vol 3. N0. 1 $6.95 THE P O L I T I C S O F B E C O M I N G The Color of the Independent Movement JACQUELINE SALIT Title of Article adj. 1 of, or pertaining to, the movement of independent voters for political recognition and popular power __ n. an independent voter in the post-Perot era, without traditional ideological attachments, seeking the overthrow of bipartisan political corruption __ adj. 2 of, or pertaining to, an independent political force styling itself as a postmodern progressive counterweight to neo-conservatism, or the neo-cons SPRING 2006 THE NEO-INDEPENDENT I I I TABLE OF CONTENTS Vol 3. No. 1 2 Letters 3 Editor’s Note The Color of the Independent Movement 7 Phyllis Goldberg Redistricting Movement Learns Some New Lines 11 Jacqueline Salit The Black and Independent Alliance 16 …And Justice for All? Independents File Voting Rights Complaint with the U.S. Department of Justice 28 Independent Voices 30 Talk/Talk Fred Newman and Jacqueline Salit take on the talking heads 40 Texas Article To come COVER PHOTO: DAVID BELMONT SPRING 2006 THE NEO-INDEPENDENT LETTERS A Welcome Voice Defining “Independent” I have read different magazines As a charter subscriber, I am now with varying levels of satisfaction. -

Bowling Alone, but Online Together? Virtual Communities and American Public Life

Bowling Alone, But Online Together? Virtual Communities and American Public Life Felicia Wu Song Charlottesville, Virginia B.A., Yale University, 1994 M.A., Northwestern University, 1996 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Sociology University of Virginia May, 2005 Bowling Alone, but Online Together? Virtual Communities and American Public Life Felicia Wu Song James Davison Hunter, Chair Department of Sociology University of Virginia ABSTRACT The integration of new communication technologies into the fabric of everyday life has raised important questions about their effects on existing conceptions and practices of community, relationship, and personal identity. How do these technologies mediate and reframe our experience of social interactions and solidarity? What are the cultural and social implications of the structural changes that they introduce? This dissertation critically considers these questions by examining the social and technological phenomenon of online communities and their role in the ongoing debates about the fate of American civil society. In light of growing concerns over declining levels of trust and civic participation expressed by scholars such as Robert Putnam, many point to online communities as possible catalysts for revitalizing communal life and American civic culture. To many, online communities appear to render obsolete not only the barriers of space and time, but also problems of exclusivity and prejudice. Yet others remain skeptical of the Internet's capacity to produce the types of communities necessary for building social capital. After reviewing and critiquing the dominant perspectives on evaluating the democratic efficacy of online communities, this dissertation suggests an alternative approach that draws from the conceptual distinctions made by Mark E. -

Defendants' Memorandum of Law In

Case 1:20-cv-04148-JGK Document 39 Filed 07/02/20 Page 1 of 46 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK SAM PARTY OF NEW YORK and Case No. 1:20-cv-00323 MICHAEL J. VOLPE, Hon. John G. Koeltl Plaintiffs, v. PETER S. KOSINSKI, et al., Defendants. LINDA HURLEY, et al., Case No. 1:20-cv-04148 Plaintiffs, Hon. John G. Koeltl v. PETER S. KOSINSKI, et al., Defendants. DEFENDANTS’ MEMORANDUM OF LAW IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS’ MOTIONS FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTIONS HARRIS BEACH PLLC 677 Broadway, Suite 1101 Albany, NY 12207 T: 518.427.9700 F: 518.427.0235 Attorneys for Defendants Case 1:20-cv-04148-JGK Document 39 Filed 07/02/20 Page 2 of 46 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ......................................................................................................... iii PRELIMINARY STATEMENT .................................................................................................... 1 STATEMENT OF FACTS ............................................................................................................. 4 A. Statutory Background .......................................................................................................4 B. New York’s Campaign Finance Reform Commission .....................................................6 C. The Legislature Adopts the Commission’s Recommendations in the 2021 Budget ......................................................................................................................8 D. Plaintiffs and Their Challenges .........................................................................................8 -

2020.01.14 Dkt. 1 — Complaint

Case 1:20-cv-00323 Document 1 Filed 01/14/20 Page 1 of 28 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK SAM PARTY OF NEW YORK and MICHAEL J. VOLPE, Civil Action No. 20 CIV ____- Plaintiffs, COMPLAINT vs. ANDREW CUOMO, as the Governor of the State of New York; ANDREA STEWART-COUSINS, as the Temporary President and Majority Leader of the New York State Senate; JOHN J. FLANAGAN, as the Minority Leader of the New York State Senate; CARL E. HEASTIE, as the Speaker of the New York State Assembly; BRIAN KOLB, as the Minority Leader of the New York State Assembly; PETER S. KOSINSKI, as the Co- Chair of the New York State Board of Elections; DOUGLAS A. KELLNER, as the Co-Chair of the New York State Board of Elections; ANDREW J. SPANO, as a Commissioner of the New York State Board of Elections; TODD D. VALENTINE, as Co-Executive Director of the New York State Board of Elections; and ROBERT A. BREHM, as Co-Executive Director of the New York State Board of Elections, Defendants. INTRODUCTION 1. New York has changed its electoral laws to bar small political parties from the ballot unless they choose to nominate a candidate for President of the United States. That requirement is repugnant to the Constitution and the laws of the United States. 2. Plaintiff SAM Party of New York is a recognized political “party” under New York law that focuses on nominating candidates for village, town, county, and statewide office. SAM believes that our electoral system is broken and that the two main political parties are focused solely on defeating each other, rather than serving the people. -

The Misguided Rejection of Fusion Voting by State Legislatures and the Supreme Court

THE MISGUIDED REJECTION OF FUSION VOTING BY STATE LEGISLATURES AND THE SUPREME COURT LYNN ADELMAN* The American political system is no longer perceived as the gold standard that it once was.1 And with good reason. “The United States ranks outside the top 20 countries in the Corruption Perception Index.”2 “U.S. voter turnout trails most other developed countries.”3 Congressional approval ratings are around 20%, “and polling shows that partisan animosity is at an all-time high.”4 Beginning in the 1970’s, “the economy stopped working the way it had for all of our modern history—with steady generational increases in income and living standards.”5 Since then, America has been plagued by unprecedented inequality and large portions of the population have done worse not better.6 In the meantime, the Electoral College gives the decisive losers of the national popular vote effective control of the national government.7 Under these circumstances, many knowledgeable observers believe that moving toward a multiparty democracy would improve the quality of representation, “reduce partisan gridlock, lead to positive incremental change and increase . voter satisfaction.”8 And there is no question that third parties can provide important public benefits. They bring substantially more variety to the country’s political landscape. Sometimes in American history third parties have brought neglected points of view to the forefront, articulating concerns that the major parties failed to address.9 For example, third parties played an important role in bringing about the abolition of slavery and the establishment of women’s suffrage.10 The Greenback Party and the Prohibition Party both raised issues that were otherwise ignored.11 Third parties have also had a significant impact on European democracies as, for example, when the Green Party in Germany raised environmental issues that the social democrats and conservatives ignored.12 If voters had more choices, it is likely that they would show up more often at the * Lynn Adelman is a U.S. -

“Sore- Loser” Statute, Which Prohibits a Candidate

SOUTH CAROLINA GREEN PARTY V. SOUTH CAROLINA STATE ELECTION COMMISSION South Carolina, like many other states, has what is commonly called a “sore- loser” statute, which prohibits a candidate who loses a party primary from appearing on the ballot in the general election as that party’s candidate.1 But South Carolina also allows individuals to run as “fusion candidates,” which are candidates who appear as the nominee of at least two certified political parties on the general election ballot.2 Under the practice called electoral fusion, these fusion candidates receive all the votes cast for them in the general election, in their capacities as nominees for individual parties combined.3 In other words, the votes follow the person, not the party. Even so, should a would-be fusion candidate lose the nomination contest for any of its intended parties, the sore- loser statute would appear to bar that candidate’s name from appearing on the general election ballot for any of its intended parties.4 Last year, in South Carolina Green Party v. South Carolina State Election Commission, the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit upheld a district court decision in favor of the defendants, a group consisting of the South Carolina State Election Commission, members thereof, and the Charleston County Democratic Party.5 The plaintiffs in the case, the South Carolina Green Party; its 2008 nominee for South Carolina House Seat 115, Eugene Platt; and Robert Dunham, a citizen-supporter of Platt, asserted that the sore-loser statute violated the