Alaris Capture Pro Software

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Short Description of the Original Building Accounts of Kikby Muxloe Castle, Leicestershire

ORIGINAL BUILDING ACCOUNTS OF KIRBY MUXLOE OASTLE. 87 A SHORT DESCRIPTION OF THE ORIGINAL BUILDING ACCOUNTS OF KIKBY MUXLOE CASTLE, LEICESTERSHIRE, RECENTLY DISCOVEBED AT THE MANOR HOUSE, ASHBYDELAZoUOH. BY THOS. H. FOBBROOKE, F.S.A. The Manuscripts and other Documents belonging to the ancient family of Hastings, of AshbydelaZouch, are amongst the finest and most interesting in the kingdom. After the destruction of their ancient castle at Ashby, these papers were stored at Donington Hall, but since the recent sale of that estate have been housed at the Manor House at Ashby delaZouch, where through the kindness of Lady Maud Hastings, they were exhibited to, and much admired by, the members of the Leicestershire Archaeological Society, on the occasion of their annual excursion last year. One of the most interesting of these MSS. is a XV. century book of building accounts, relating to the erection of Kirby Castle by William Lord Hastings, between the years 1480 and 1484. This book was first shewn to me when I was measuring the ruined castle at Ashby, the drawings of which were afterwards published by this Society in the Reports and Papers of the Asso ciated Societies' Publication, Vol. XXI., Part 1 (1911). On the discovery that the accounts related entirely to Kirby Castle, they were entrusted to my care through the kindness of Lady Maud Hastings, and I at once communicated with C. R. Peers, Esq., Secretary of the Society of Antiquaries, who at that time was engaged on the conservation of the old ruin at Kirby, under the Ancient Monuments Act. -

Rothley Brook Meadow Green Wedge Review

Rothley Brook Meadow Green Wedge Review September 2020 2 Contents Rothley Brook Meadow Green Wedge Review .......................................................... 1 August 2020 .............................................................................................................. 1 Role of this Evidence Base study .......................................................................... 6 Evidence Base Overview ................................................................................... 6 1. Introduction ................................................................................................. 7 General Description of Rothley Brook Meadow Green Wedge........................... 7 Figure 1: Map showing the extent of the Rothley Brook Meadow Green Wedge 8 2. Policy background ....................................................................................... 9 Formulation of the Green Wedge ....................................................................... 9 Policy context .................................................................................................... 9 National Planning Policy Framework (2019) ...................................................... 9 Core Strategy (December 2009) ...................................................................... 10 Site Allocations and Development Management Policies Development Plan Document (2016) ............................................................................................. 10 Landscape Character Assessment (September 2017) .................................... -

Castle Studies Group Bibliography No. 23 2010 CASTLE STUDIES: RECENT PUBLICATIONS – 23 (2010)

Castle Studies Group Bibliography No. 23 2010 CASTLE STUDIES: RECENT PUBLICATIONS – 23 (2010) By John R. Kenyon Introduction This is advance notice that I plan to take the recent publications compilation to a quarter century and then call it a day, as I mentioned at the AGM in Taunton last April. So, two more issues after this one! After that, it may be that I will pass on details of major books and articles for a mention in the Journal or Bulletin, but I think that twenty-five issues is a good milestone to reach, and to draw this service to members to a close, or possibly hand on the reins, if there is anyone out there! No sooner had I sent the corrected proof of last year’s Bibliography to Peter Burton when a number of Irish items appeared in print. These included material in Archaeology Ireland, the visitors’ guide to castles in that country, and then the book on Dublin from Four Court Press, a collection of essays in honour of Howard Clarke, which includes an essay on Dublin Castle. At the same time, I noted that a book on medieval travel had a paper by David Kennett on Caister Castle and the transport of brick, and this in turn led me to a paper, published in 2005, that has gone into Part B, Alasdair Hawkyard’s important piece on Caister. Wayne Cocroft of English Heritage contacted me in July 2009, and I quote: - “I have just received the latest CSG Bibliography, which has prompted me to draw the EH internal report series to your attention. -

Memories of Sheila Mileham

Memories of Sheila Mileham I first met Sheila not long after the The children loved it, asking questions about Last year the KMLHG website received an enquiry asking if we John joined Leicester Corporation as a councillor in 1906 inaugural meeting of our History the school and life in the village long ago. had any information on houses and land on Hinckley Road. The and was elected the 469th Mayor of the Borough in 1913 - Group. She was, like me, one of the 25 Sheila was unusually quiet, but I just thought properties were Greendale, Farfield, Whitecroft and 14. He became an Alderman in 1916, when he was also people who went along to the first she was perhaps feeling a bit under the Applegarth. These properties, all occupied by the Frears Provincial Grand Secretary of the Leicester Freemasons, meeting and who joined the new group. weather. A couple of weeks later, I had family were interconnected through the fields and spinney. Visiting Committee Chairman of the lunatic asylum, and Not long after, we also formed a arranged to pick her up and take her to see the We were unfortunately not able provide much information, education committee member of Wyggeston Girls’ Grammar Research Group, which met in the room display of Christmas trees in St. Bart’s. Again, but during the research a very interesting family was School. at the library once a month. Our main she was not like her old self, always so discovered. John died in 1937. Minnie remained at Hillsborough for a aim was to research and share enthusiastic and happy to be wherever we John Russell Frears was born in Eskdale, Cumberland in 1835 while but lived with daughter Constance at Whitecroft at the information about the village of Kirby were going. -

Newsletter No. 10 February 2021 a Request Mike Cooper

We have been very fortunate to have been given access to The proceeds of these productions, flower shows and many photographs and documents in the possession of the bazaars went towards the recasting of the church bells Wilshere family. In particular, Jonathan Wilshere and the provision of a new organ. Newsletter No. 10 February 2021 accumulated quite a collection, which includes a Mention should be made of the first Band of Hope held in Hi and welcome to ourlatest KMLHG Newsletter. newspaper cutting of an anonymous “letter to the editor” the old Free Church at the bottom of the village which was concerning memories of Kirby Muxloe. I think it was sent Mike Gould (Chair) Val Knott (Secretary) afterwards transferred to the new church at the other around 1933 and refers back to a period of time that Kate Traill (Treasurer) Judith Upton (Archivist) end. spanned 1910, when the Barwell Road Primary School Kerry Burdett opened. I reproduce it here exactly as it was written. If Many thanks are due to the residents the other side of the We start by again turning back the clock and anyone can add to it, or tell me who “Old School Boy” from brook for their activities in the cause of the enlightenment Brazil Street was, I would be interested to hear from you. of the life of the residents of the village. continuing on our virtual walk around 1945 Kirby. Your contributor's article on Kirby Muxloe was certainly Well do I remember the scare that was caused when the majority of the school children were taken away with ¬ We have now reached “The Towers”, a large very interesting, but much more could have been added house built in the Victorian Gothic style that would regarding the early days of the village. -

King Richard III in Leicester & Leicestershire

King Richard III in Leicester & Leicestershire Day 1 CITY OF LEICESTER St Martin's Centre, Peacock Lane, Leicester Welcome to Leicester with tea, coffee, refreshments and welcome talk Originally built in 1877, St Martin’s Centre is a stunning Grade II listed former Grammar School with an elegant mix of period features with contemporary styling, a beautifully restored hall and several smaller meeting rooms and is the ideal welcome to the city. The centre is situated in the heart of Leicester’s Old Town next to the Cathedral, Guildhall and the King Richard III Visitor Centre. Leicester Cathedral, Guided Walk: King Richard III - The Leicester Connection This walk is organised by an accredited Blue Badge Guide and will cover the historic areas of the city relating to King Richard III’s final days in the city. The walk will last approximately 1hr 45mins. King Richard III Visitor Centre – Richard III: Dynasty, Death and Discovery The Visitor Centre includes a stunning display of artefacts and material found in the search for King Richard III and a medieval storyline followed by the science behind the discovery of the King. The centre is also home to a gift shop, café and a seating area within the graveside memorial garden. Lunch Leicester Cathedral Built on the site of a Roman temple and dedicated to St Martin of Tours, Leicester Cathedral has been embedded in the life of the local community since medieval times. There has been a major memorial to King Richard III in the Chancel of the Cathedral since 1980. This has been the focus for remembrance, particularly on the anniversary of the Battle of Bosworth. -

The Rise of the Anti-Clockwise Newel Stair

The Rise of the Anti-clockwise Newel Stair Newark Castle. Gatehouse, c. 1130-40. The wide anticlockwise spiral stair rising to the audience chamber over gatehouse passage. THE CASTLE STUDIES GROUP JOURNAL NO 25: 2011-12 113 The Rise of the Anti-clockwise Newel Stair The Rise of the Anticlockwise Newel Stair Abstract: The traditional castle story dictates that all wind- ing, newel, turnpike or spiral staircases in medi- eval great towers, keep-gatehouses, tower houses and mural wall towers ascended clockwise. This orthodoxy has it that it offered a real functional military advantage to the defender; a persistent theory that those defending the stair from above had the greatest space in which to use their right- handed sword arm. Conversely, attackers mount- ing an upward assault in a clockwise or right- handed stair rotation would not have unfettered use of their weaponry or have good visibility of their intended victim, as their right sword hand would be too close to the central newel. Fig. 1. Diagrammatic view of Trajan’s Column, Rome, Whilst there may be other good reasons for AD 130, viewed from the east. The interior anticlock- clockwise (CW) stairs, the oft-repeated thesis sup- wise (ACW) stair made from solid marble blocks. porting a military determinism for clockwise stairs is here challenged. The paper presents a Origins and Definitions. corpus of more than 85 examples of anticlockwise The spiral, also known as a vice, helix, helical, (ACW) spiral stairs found in medieval castles in winding, turnpike, or circular stair is an ancient England and Wales dating from the 1070s device, and existing anticlockwise (or counter- through to the 1500s. -

Pre-1500 Military Sites Scheduling Selection Guide Summary

Pre-1500 Military Sites Scheduling Selection Guide Summary Historic England’s scheduling selection guides help to define which archaeological sites are likely to meet the relevant tests for national designation and be included on the National Heritage List for England. For archaeological sites and monuments, they are divided into categories ranging from Agriculture to Utilities and complement the listing selection guides for buildings. Scheduling is applied only to sites of national importance, and even then only if it is the best means of protection. Only deliberately created structures, features and remains can be scheduled. The scheduling selection guides are supplemented by the Introductions to Heritage Assets which provide more detailed considerations of specific archaeological sites and monuments. This selection guide offers an overview of archaeological monuments or sites designed to have a military function and likely to be deemed to have national importance, and sets out criteria to establish for which of those scheduling may be appropriate. The guide aims to do two things: to set these sites within their historical context, and to give an introduction to some of the overarching and more specific designation considerations. This document has been prepared by Listing Group. It is one is of a series of 18 documents. This edition published by Historic England July 2018. All images © Historic England unless otherwise stated. Please refer to this document as: Historic England 2018 Pre-1500 Military Sites: Scheduling Selection Guide. Swindon. Historic England. HistoricEngland.org.uk/listing/selection-criteria/scheduling-selection/ Front cover The castle at Burton-in-Lonsdale, North Yorkshire was built around 1100 as a ringwork; later it was reconstructed as a motte with two baileys. -

Archaeology Archaeology

https://festival.archaeologyuk.org/ https://festival.archaeologyuk.org/ T0025 - May 2019 - Designed and printed by Leicestershire County Council. Tel: 0116 305 6128 305 0116 Tel: Council. County Leicestershire by printed and Designed - 2019 May - T0025 @LeicsArchFest #leicsarchfest @LeicsArchFest @LeicsArchFest http://leicsfieldworkers.co.uk/festival-of-archaeology https://festival.archaeologyuk.org/ https://festival.archaeologyuk.org/ See back page for details! for page back See www.lihs.org.uk publications. and archaeology with digs, talks and and talks digs, with archaeology and Sunday June 29th: 11am – 4pm. – 11am 29th: June Sunday An active society studying Industrial history history Industrial studying society active An www.le.ac.uk/ulas Leicester. in based Society History Industrial Leicestershire Award winning commercial archaeology unit unit archaeology commercial winning Award OPEN DAY & FESTIVAL LAUNCH FESTIVAL & DAY OPEN Archaeological Services Archaeological [email protected] Leicester of University BRADGATE PARK EXCAVATION EXCAVATION PARK BRADGATE Macgregor: Jennifer Contact: museum. the of reopening www.archaeologyuk.org/cbaem continue their support and look forward to the the to forward look and support their continue individuals. and societies moment The Friends of Jewry Wall Museum Museum Wall Jewry of Friends The moment An umbrella group for local archaeology archaeology local for group umbrella An Midlands East Although the Museum is closed at the the at closed is Museum the Although The Friends of Jewry -

An August Encounter

....... s Richard III Society, Inc. Volume XXXVI No. 1&2 Spring & Summer, 2006 An August Encounter An unlikely meeting, (more symbolic than historically factual) is the subject for this appropriate “Bosworth” month window display of a pair of intricately-painted heraldic jousting model figures, depicting Henry Tudor and Richard III: “The Armoury of St. James’s,” 17 Piccadilly Arcade, London SW1Y6NH (www.armoury.co.uk/home - these pewter mounted knights range from £800 - £1,000!) — Geoffrey Wheeler REGISTER STAFF EDITOR: Carole M. Rike 48299 Stafford Road • Tickfaw, LA 70466 985-350-6101 ° 504-952-4984 (cell) email: [email protected] ©2006 Richard III Society, Inc., American Branch. No part may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means — mechanical, RICARDIAN READING EDITOR: Myrna Smith electrical or photocopying, recording or information storage retrieval — 2784 Avenue G • Ingleside, TX 78362 without written permission from the Society. Articles submitted by (361) 332-9363 • email: [email protected] members remain the property of the author. The Ricardian Register is published four times per year. Subscriptions are available at $20.00 annually. ARTIST: Susan Dexter 1510 Delaware Avenue • New Castle, PA 16105-2674 In the belief that many features of the traditional accounts of the character and career of Richard III are neither supported by sufficient CROSSWORD: Charlie Jordan evidence nor reasonably tenable, the Society aims to promote in every [email protected] possible way research into the life and times of Richard III, and to secure a re-assessment of the material relating to the period, and of the role in English history of this monarch The Richard III Society is a nonprofit, educational corporation. -

Grey and Hastings Families Had Benefited from This and Acquired a Lot of Former Monastic Property

The Greys –Beginnings. The Greys and the Hastings families both sprang to prominence in the mid 13th century. Our local line sprang from John Grey(d.1265) and his second wife; their first son, Reginald (d.1308) fought for Edward l in Wales and served in Parliament. His son John fought at Bannockburn. We do not know much more until 3 generations later when Reginald Grey was captured by the Welsh chief Owen Glendower in 1402. His ransom cost £10.000 marks. He died peacefully in his eighties. The Greys of Groby. It was the marriage of Reginald’s eldest son, Edward d 1458), to Elizabeth Ferrers of Groby that gave rise to our local line. The Ferrers were a high ranking noble family and Elizabeth was the sole heiress, so this was a considerable advance in the family fortunes. Sir Edward could now boast the ownership of land in five counties. He was now titled Lord Ferrers of Groby. It was his son, Sir John Grey , who married a lady called Elizabeth Woodville but backed the Lancastrian cause in the Wars of the Roses, and was killed at the First Battle of St Albans in 1461. This left Elizabeth as a widow. The Hastings Family. The Hastings family mainly centred on Kirby Muxloe and Ashby de la Zouch. Like the Greys they cannot be traced back to the Norman Conquest but rose to power from fairly humble origins. Because they did this after the Greys the Greys regarded them as upstarts. The two most famous members were William. Lord Hastings, executed by Richard lll, and Henry Hastings, Third Earl of Huntingdon, who was one of Elizabeth l’s most trusted advisers who was once given the job of keeping an eye on Mary, Queen of Scots. -

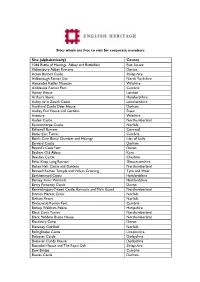

Site (Alphabetically)

Sites which are free to visit for corporate members Site (alphabetically) County 1066 Battle of Hastings, Abbey and Battlefield East Sussex Abbotsbury Abbey Remains Dorset Acton Burnell Castle Shropshire Aldborough Roman Site North Yorkshire Alexander Keiller Museum Wiltshire Ambleside Roman Fort Cumbria Apsley House London Arthur's Stone Herefordshire Ashby de la Zouch Castle Leicestershire Auckland Castle Deer House Durham Audley End House and Gardens Essex Avebury Wiltshire Aydon Castle Northumberland Baconsthorpe Castle Norfolk Ballowall Barrow Cornwall Banks East Turret Cumbria Bant's Carn Burial Chamber and Halangy Isles of Scilly Barnard Castle Durham Bayard's Cove Fort Devon Bayham Old Abbey Kent Beeston Castle Cheshire Belas Knap Long Barrow Gloucestershire Belsay Hall, Castle and Gardens Northumberland Benwell Roman Temple and Vallum Crossing Tyne and Wear Berkhamsted Castle Hertfordshire Berney Arms Windmill Hertfordshire Berry Pomeroy Castle Devon Berwick-upon-Tweed Castle, Barracks and Main Guard Northumberland Binham Market Cross Norfolk Binham Priory Norfolk Birdoswald Roman Fort Cumbria Bishop Waltham Palace Hampshire Black Carts Turret Northumberland Black Middens Bastle House Northumberland Blackbury Camp Devon Blakeney Guildhall Norfolk Bolingbroke Castle Lincolnshire Bolsover Castle Derbyshire Bolsover Cundy House Derbyshire Boscobel House and The Royal Oak Shropshire Bow Bridge Cumbria Bowes Castle Durham Boxgrove Priory West Sussex Bradford-on-Avon Tithe Barn Wiltshire Bramber Castle West Sussex Bratton Camp and