Cryptocurrency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

YEUNG-DOCUMENT-2019.Pdf (478.1Kb)

Useful Computation on the Block Chain The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Yeung, Fuk. 2019. Useful Computation on the Block Chain. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37364565 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA 111 Useful Computation on the Block Chain Fuk Yeung A Thesis in the Field of Information Technology for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University November 2019 Copyright 2019 [Fuk Yeung] Abstract The recent growth of blockchain technology and its usage has increased the size of cryptocurrency networks. However, this increase has come at the cost of high energy consumption due to the processing power needed to maintain large cryptocurrency networks. In the largest networks, this processing power is attributed to wasted computations centered around solving a Proof of Work algorithm. There have been several attempts to address this problem and it is an area of continuing improvement. We will present a summary of proposed solutions as well as an in-depth look at a promising alternative algorithm known as Proof of Useful Work. This solution will redirect wasted computation towards useful work. We will show that this is a viable alternative to Proof of Work. Dedication Thank you to everyone who has supported me throughout the process of writing this piece. -

Beauty Is Not in the Eye of the Beholder

Insight Consumer and Wealth Management Digital Assets: Beauty Is Not in the Eye of the Beholder Parsing the Beauty from the Beast. Investment Strategy Group | June 2021 Sharmin Mossavar-Rahmani Chief Investment Officer Investment Strategy Group Goldman Sachs The co-authors give special thanks to: Farshid Asl Managing Director Matheus Dibo Shahz Khatri Vice President Vice President Brett Nelson Managing Director Michael Murdoch Vice President Jakub Duda Shep Moore-Berg Harm Zebregs Vice President Vice President Vice President Shivani Gupta Analyst Oussama Fatri Yousra Zerouali Vice President Analyst ISG material represents the views of ISG in Consumer and Wealth Management (“CWM”) of GS. It is not financial research or a product of GS Global Investment Research (“GIR”) and may vary significantly from those expressed by individual portfolio management teams within CWM, or other groups at Goldman Sachs. 2021 INSIGHT Dear Clients, There has been enormous change in the world of cryptocurrencies and blockchain technology since we first wrote about it in 2017. The number of cryptocurrencies has increased from about 2,000, with a market capitalization of over $200 billion in late 2017, to over 8,000, with a market capitalization of about $1.6 trillion. For context, the market capitalization of global equities is about $110 trillion, that of the S&P 500 stocks is $35 trillion and that of US Treasuries is $22 trillion. Reported trading volume in cryptocurrencies, as represented by the two largest cryptocurrencies by market capitalization, has increased sixfold, from an estimated $6.8 billion per day in late 2017 to $48.6 billion per day in May 2021.1 This data is based on what is called “clean data” from Coin Metrics; the total reported trading volume is significantly higher, but much of it is artificially inflated.2,3 For context, trading volume on US equity exchanges doubled over the same period. -

On the Relationship of Cryptocurrency Price with US Stock and Gold Price Using Copula Models

mathematics Article On the Relationship of Cryptocurrency Price with US Stock and Gold Price Using Copula Models Jong-Min Kim 1 , Seong-Tae Kim 2 and Sangjin Kim 3,* 1 Statistics Discipline, University of Minnesota at Morris, Morris, MN 56267, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Mathematics, North Carolina A&T State University, Greensboro, NC 27411, USA; [email protected] 3 Department of Management and Information Systems, Dong-A University, Busan 49236, Korea * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 15 September 2020; Accepted: 20 October 2020; Published: 23 October 2020 Abstract: This paper examines the relationship of the leading financial assets, Bitcoin, Gold, and S&P 500 with GARCH-Dynamic Conditional Correlation (DCC), Nonlinear Asymmetric GARCH DCC (NA-DCC), Gaussian copula-based GARCH-DCC (GC-DCC), and Gaussian copula-based Nonlinear Asymmetric-DCC (GCNA-DCC). Under the high volatility financial situation such as the COVID-19 pandemic occurrence, there exist a computation difficulty to use the traditional DCC method to the selected cryptocurrencies. To solve this limitation, GC-DCC and GCNA-DCC are applied to investigate the time-varying relationship among Bitcoin, Gold, and S&P 500. In terms of log-likelihood, we show that GC-DCC and GCNA-DCC are better models than DCC and NA-DCC to show relationship of Bitcoin with Gold and S&P 500. We also consider the relationships among time-varying conditional correlation with Bitcoin volatility, and S&P 500 volatility by a Gaussian Copula Marginal Regression (GCMR) model. The empirical findings show that S&P 500 and Gold price are statistically significant to Bitcoin in terms of log-return and volatility. -

Evmpatch: Timely and Automated Patching of Ethereum Smart Contracts

EVMPatch: Timely and Automated Patching of Ethereum Smart Contracts Michael Rodler Wenting Li Ghassan O. Karame University of Duisburg-Essen NEC Laboratories Europe NEC Laboratories Europe Lucas Davi University of Duisburg-Essen Abstract some of these contracts hold, smart contracts have become an appealing target for attacks. Programming errors in smart Recent attacks exploiting errors in smart contract code had contract code can have devastating consequences as an attacker devastating consequences thereby questioning the benefits of can exploit these bugs to steal cryptocurrency or tokens. this technology. It is currently highly challenging to fix er- rors and deploy a patched contract in time. Instant patching is Recently, the blockchain community has witnessed several especially important since smart contracts are always online incidents due smart contract errors [7, 39]. One especially due to the distributed nature of blockchain systems. They also infamous incident is the “TheDAO” reentrancy attack, which manage considerable amounts of assets, which are at risk and resulted in a loss of over 50 million US Dollars worth of often beyond recovery after an attack. Existing solutions to Ether [31]. This led to a highly debated hard-fork of the upgrade smart contracts depend on manual and error-prone pro- Ethereum blockchain. Several proposals demonstrated how to defend against reentrancy vulnerabilities either by means of cesses. This paper presents a framework, called EVMPATCH, to instantly and automatically patch faulty smart contracts. offline analysis at development time or by performing run-time validation [16, 23, 32, 42]. Another infamous incident is the EVMPATCH features a bytecode rewriting engine for the pop- ular Ethereum blockchain, and transparently/automatically parity wallet attack [39]. -

![Pdf [2] Popper, N](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0656/pdf-2-popper-n-210656.webp)

Pdf [2] Popper, N

Journal of Mathematical Finance, 2021, 11, 495-511 https://www.scirp.org/journal/jmf ISSN Online: 2162-2442 ISSN Print: 2162-2434 The Investors’ Behavior towards the Relationship between Bitcoin, Litcoin, Dash Coins, and Gold: A Portfolio Modeling Approach Asma Maghrebi, Fathi Abid Department of Management, Faculty of Economics and Management, Sfax, Tunisia How to cite this paper: Maghrebi, A. and Abstract Abid, F. (2021) The Investors’ Behavior towards the Relationship between Bitcoin, This study considers a market-based economy that is composed of two asset Litcoin, Dash Coins, and Gold: A Portfolio classes: one is a digital, cryptocurrency, and the other is real, gold. We dem- Modeling Approach. Journal of Mathemat- onstrated that coins like (BTC, LTC, and DASH) can substitute a traditional ical Finance, 11, 495-511. https://doi.org/10.4236/jmf.2021.113028 safe haven “gold” in an intertemporal investment portfolio to become a new form of safe haven. The cryptocurrency follows a Jump-diffusion process. How- Received: June 29, 2021 ever, gold prices follow an Ornstein-Uhlenbek process to characterize the Accepted: August 16, 2021 stochastic nature of the market. The stochastic optimal control approach, Published: August 19, 2021 combined with the strategic asset allocation and the intertemporal utility Copyright © 2021 by author(s) and theory, are used through the derivation of a Hamilton-Jacobi-Bellman (HJB) Scientific Research Publishing Inc. equation to determine an explicit solution of the optimal allocation problem This work is licensed under the Creative for investors with CRRA utility function. We considered the Gamma Lévy Commons Attribution International process to solve the optimization problem. -

Decentralized Autonomous Organization Supplement."

ARTICLE 1 - PROVISIONS 17-31-101. Short title. This chapter shall be known and may be cited as the "Wyoming Decentralized Autonomous Organization Supplement." 17-31-102. Definitions. (a) As used in this chapter: (i) "Blockchain" means as defined in W.S. 34-29- 106(g)(i); (ii) "Decentralized autonomous organization" means a limited liability company organized under this chapter; (iii) "Digital asset" means as defined in W.S. 34-29- 101(a)(i); (iv) "Limited liability autonomous organization" or "LAO" means a decentralized autonomous organization; (v) "Majority of the members," means the approval of more than fifty percent (50%) of participating membership interests in a vote for which a quorum of members is participating. A person dissociated as a member as set forth in W.S. 17-29-602 shall not be included for the purposes of calculating the majority of the members; (vi) "Membership interest" means a member's ownership share in a member managed decentralized autonomous organization, which may be defined in the entity's articles of organization, smart contract or operating agreement. A membership interest may also be characterized as either a digital security or a digital consumer asset as defined in W.S. 34-29-101, if designated as such in the organization's articles of organization or operating agreement; (vii) "Open blockchain" means a blockchain as defined in W.S. 34-29-106(g)(i) that is publicly accessible and its ledger of transactions is transparent; (viii) "Quorum" means a minimum requirement on the sum of membership interests participating in a vote for that vote to be valid; 1 (ix) "Smart contract" means an automated transaction, as defined in W.S. -

Stable Coin Evolution and Market Trends

Stable Coin evolution and market trends Key observations PwC’s market analysis | October 2018 www.pwc.com.au 2 Stable Coin Evolution and Market Trends Stable Coin Evolution and Market Trends 3 Key observations in 5 9 Presently there are at least 75 projects Stablecoins should not be equated with the Stable Coin Evolution that could be considered “stable coin” asset they are backed by in terms of safety projects. With the deluge of projects and and stability. The legitimacy and long term the amount of capital they have raised, the viability of some stablecoins will be at the The stable coin evolution and trends discussed in this paper are the interpretation of information cryptocurrency space could enter into its whim of investor expectations. Understanding gathered via market research and questionnaires sent to 50+ stable coin projects. They are own form of quantitative easing. This may be what these coins truly represent and their therefore interpretation of this data from the authors at the time this paper was drafted. driven by fiat or asset backed funds entering functionalities is a must for anyone who is the ecosystem that could find it’s way into looking to deploy capital into this market. George Samman investing into many of the cryptocurrency Co-Authors: John(3rd party Shipman expert) (PwC) George Samman projects trading on exchanges. [email protected] (3rd party expert) [email protected] https://www.linkedin.com/ in/georgesamman/ 10 6 Fiat-backed stablecoins can never be100% Executive Summary censorship resistant, permission-less and Exchanges are hedging themselves against trust-less. -

Banking on Bitcoin: BTC As Collateral

Banking on Bitcoin: BTC as Collateral Arcane Research Bitstamp Arcane Research is a part of Arcane Crypto, Bitstamp is the world’s longest-running bringing data-driven analysis and research cryptocurrency exchange, supporting to the cryptocurrency space. After launch in investors, traders and leading financial August 2019, Arcane Research has become institutions since 2011. With a proven track a trusted brand, helping clients strengthen record, cutting-edge market infrastructure their credibility and visibility through and dedication to personal service with a research reports and analysis. In addition, human touch, Bitstamp’s secure and reliable we regularly publish reports, weekly market trading venue is trusted by over four million updates and articles to educate and share customers worldwide. Whether it’s through insights. their intuitive web platform and mobile app or industry-leading APIs, Bitstamp is where crypto enters the world of finance. For more information, visit www.bitstamp.net 2 Banking on Bitcoin: BTC as Collateral Banking on bitcoin The case for bitcoin as collateral The value of the global market for collateral is estimated to be close to $20 trillion in assets. Government bonds and cash-based securities alike are currently the most important parts of a well- functioning collateral market. However, in that, there is a growing weakness as rehypothecation creates a systemic risk in the financial system as a whole. The increasing reuse of collateral makes these assets far from risk-free and shows the potential instability of the financial markets and that it is more fragile than many would like to admit. Bitcoin could become an important part of the solution and challenge the dominating collateral assets in the future. -

Vulnerability of Blockchain Technologies to Quantum Attacks

Vulnerability of Blockchain Technologies to Quantum Attacks Joseph J. Kearneya, Carlos A. Perez-Delgado a,∗ aSchool of Computing, University of Kent, Canterbury, Kent CT2 7NF United Kingdom Abstract Quantum computation represents a threat to many cryptographic protocols in operation today. It has been estimated that by 2035, there will exist a quantum computer capable of breaking the vital cryptographic scheme RSA2048. Blockchain technologies rely on cryptographic protocols for many of their essential sub- routines. Some of these protocols, but not all, are open to quantum attacks. Here we analyze the major blockchain-based cryptocurrencies deployed today—including Bitcoin, Ethereum, Litecoin and ZCash, and determine their risk exposure to quantum attacks. We finish with a comparative analysis of the studied cryptocurrencies and their underlying blockchain technologies and their relative levels of vulnerability to quantum attacks. Introduction exist to allow the legitimate owner to recover this account. Blockchain systems are unlike other cryptosys- tems in that they are not just meant to protect an By contrast, in a blockchain system, there is no information asset. A blockchain is a ledger, and as central authority to manage users’ access keys. The such it is the asset. owner of a resource is by definition the one hold- A blockchain is secured through the use of cryp- ing the private encryption keys. There are no of- tographic techniques. Notably, asymmetric encryp- fline backups. The blockchain, an always online tion schemes such as RSA or Elliptic Curve (EC) cryptographic system, is considered the resource— cryptography are used to generate private/public or at least the authoritative description of it. -

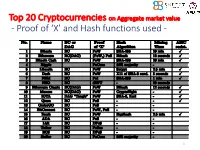

Proof of 'X' and Hash Functions Used

Top 20 Cryptocurrencies on Aggregate market value - Proof of ‘X’ and Hash functions used - 1 ISI Kolkata BlockChain Workshop, Nov 30th, 2017 CRYPTOGRAPHY with BlockChain - Hash Functions, Signatures and Anonymization - Hiroaki ANADA*1, Kouichi SAKURAI*2 *1: University of Nagasaki, *2: Kyushu University Acknowledgements: This work is supported by: Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research of Japan Society for the Promotion of Science; Research Project Number: JP15H02711 Top 20 Cryptocurrencies on Aggregate market value - Proof of ‘X’ and Hash functions used - 3 Table of Contents 1. Cryptographic Primitives in Blockchains 2. Hash Functions a. Roles b. Various Hash functions used for Proof of ‘X’ 3. Signatures a. Standard Signatures (ECDSA) b. Ring Signatures c. One-Time Signatures (Winternitz) 4. Anonymization Techniques a. Mixing (CoinJoin) b. Zero-Knowledge proofs (zk-SNARK) 5. Conclusion 4 Brief History of Proof of ‘X’ 1992: “Pricing via Processing or Combatting Junk Mail” Dwork, C. and Naor, M., CRYPTO ’92 Pricing Functions 2003: “Moderately Hard Functions: From Complexity to Spam Fighting” Naor, M., Foundations of Soft. Tech. and Theoretical Comp. Sci. 2008: “Bitcoin: A peer-to-peer electronic cash system” Nakamoto, S. Proof of Work 5 Brief History of Proof of ‘X’ 2008: “Bitcoin: A peer-to-peer electronic cash system” Nakamoto, S. Proof of Work 2012: “Peercoin” Proof of Stake (& Proof of Work) ~ : Delegated Proof of Stake, Proof of Storage, Proof of Importance, Proof of Reserves, Proof of Consensus, ... 6 Proofs of ‘X’ 1. Proof of Work 2. Proof of Stake Hash-based Proof of ‘X’ 3. Delegated Proof of Stake 4. Proof of Importance 5. -

Cryptocurrency: the Economics of Money and Selected Policy Issues

Cryptocurrency: The Economics of Money and Selected Policy Issues Updated April 9, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45427 SUMMARY R45427 Cryptocurrency: The Economics of Money and April 9, 2020 Selected Policy Issues David W. Perkins Cryptocurrencies are digital money in electronic payment systems that generally do not require Specialist in government backing or the involvement of an intermediary, such as a bank. Instead, users of the Macroeconomic Policy system validate payments using certain protocols. Since the 2008 invention of the first cryptocurrency, Bitcoin, cryptocurrencies have proliferated. In recent years, they experienced a rapid increase and subsequent decrease in value. One estimate found that, as of March 2020, there were more than 5,100 different cryptocurrencies worth about $231 billion. Given this rapid growth and volatility, cryptocurrencies have drawn the attention of the public and policymakers. A particularly notable feature of cryptocurrencies is their potential to act as an alternative form of money. Historically, money has either had intrinsic value or derived value from government decree. Using money electronically generally has involved using the private ledgers and systems of at least one trusted intermediary. Cryptocurrencies, by contrast, generally employ user agreement, a network of users, and cryptographic protocols to achieve valid transfers of value. Cryptocurrency users typically use a pseudonymous address to identify each other and a passcode or private key to make changes to a public ledger in order to transfer value between accounts. Other computers in the network validate these transfers. Through this use of blockchain technology, cryptocurrency systems protect their public ledgers of accounts against manipulation, so that users can only send cryptocurrency to which they have access, thus allowing users to make valid transfers without a centralized, trusted intermediary. -

Blockchain & Cryptocurrency Regulation

Blockchain & Cryptocurrency Regulation Third Edition Contributing Editor: Josias N. Dewey Global Legal Insights Blockchain & Cryptocurrency Regulation 2021, Third Edition Contributing Editor: Josias N. Dewey Published by Global Legal Group GLOBAL LEGAL INSIGHTS – BLOCKCHAIN & CRYPTOCURRENCY REGULATION 2021, THIRD EDITION Contributing Editor Josias N. Dewey, Holland & Knight LLP Head of Production Suzie Levy Senior Editor Sam Friend Sub Editor Megan Hylton Consulting Group Publisher Rory Smith Chief Media Officer Fraser Allan We are extremely grateful for all contributions to this edition. Special thanks are reserved for Josias N. Dewey of Holland & Knight LLP for all of his assistance. Published by Global Legal Group Ltd. 59 Tanner Street, London SE1 3PL, United Kingdom Tel: +44 207 367 0720 / URL: www.glgroup.co.uk Copyright © 2020 Global Legal Group Ltd. All rights reserved No photocopying ISBN 978-1-83918-077-4 ISSN 2631-2999 This publication is for general information purposes only. It does not purport to provide comprehensive full legal or other advice. Global Legal Group Ltd. and the contributors accept no responsibility for losses that may arise from reliance upon information contained in this publication. This publication is intended to give an indication of legal issues upon which you may need advice. Full legal advice should be taken from a qualified professional when dealing with specific situations. The information contained herein is accurate as of the date of publication. Printed and bound by TJ International, Trecerus Industrial Estate, Padstow, Cornwall, PL28 8RW October 2020 PREFACE nother year has passed and virtual currency and other blockchain-based digital assets continue to attract the attention of policymakers across the globe.