Replayable Voting Machine Audit Logs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Box Voting Ballot Tampering in the 21St Century

This free internet version is available at www.BlackBoxVoting.org Black Box Voting — © 2004 Bev Harris Rights reserved to Talion Publishing/ Black Box Voting ISBN 1-890916-90-0. You can purchase copies of this book at www.Amazon.com. Black Box Voting Ballot Tampering in the 21st Century By Bev Harris Talion Publishing / Black Box Voting This free internet version is available at www.BlackBoxVoting.org Contents © 2004 by Bev Harris ISBN 1-890916-90-0 Jan. 2004 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form whatsoever except as provided for by U.S. copyright law. For information on this book and the investigation into the voting machine industry, please go to: www.blackboxvoting.org Black Box Voting 330 SW 43rd St PMB K-547 • Renton, WA • 98055 Fax: 425-228-3965 • [email protected] • Tel. 425-228-7131 This free internet version is available at www.BlackBoxVoting.org Black Box Voting © 2004 Bev Harris • ISBN 1-890916-90-0 Dedication First of all, thank you Lord. I dedicate this work to my husband, Sonny, my rock and my mentor, who tolerated being ignored and bored and galled by this thing every day for a year, and without fail, stood fast with affection and support and encouragement. He must be nuts. And to my father, who fought and took a hit in Germany, who lived through Hitler and saw first-hand what can happen when a country gets suckered out of democracy. And to my sweet mother, whose an- cestors hosted a stop on the Underground Railroad, who gets that disapproving look on her face when people don’t do the right thing. -

Electronic Voting & Counting Technologies

ELECTION TECHNOLOGY SERIES Electronic Voting & Counting Technologies A Guide to Conducting Feasibility Studies Ben Goldsmith Senior Electoral Advisor Electronic Voting & Counting Technologies Ben Goldsmith Senior Electoral Advisor International Foundation for Electoral Systems Electronic Voting & Counting Technologies A Guide to Conducting Feasibility Studies Ben Goldsmith Senior Electoral Advisor May 2011 Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Foundation for Electoral Systems. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Electronic Voting & Counting Technologies: A Guide to Conducting Feasibility Studies Ben Goldsmith © 2011 by IFES. All rights reserved. International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES) 1850 K Street, NW Fifth Floor Washington, D.C. 20006 U.S.A. Notice of rights All rights reserved. No part of this report can be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means without the prior permission of the publisher. Printed in USA ISBN: 1-931459-64-9 Photo Credits Cover: Ripple Effect Productions Page 36: Ripple Effect Productions Garie Briones Page 51: Lean Pasion Page 1: John Lawrence Page 59: Everton Bahl Grabski Page 9: Francisco Samões Page 70: Júlio Henrique da Silva Lopes Page 17: Ripple Effect Productions Page 75: Oliver Scott-Tomlin Page 25: João Cesário ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thanks are due to a number of colleagues and friends who were kind enough to take the time to review and comment on the initial drafts of this guide. Special thanks are due to Susanne Caarls, Peter Erben, Juhani Grossmann, Ole Holtved, Manuel Kripp, Ronan McDermott, Vladimir Pran, Amna Qayyum and Mike Yard, all of whom provided invaluable suggestions for improvements and additional areas which needed to be covered by the guide. -

On the Notion of “Software Independence” in Voting Systems

On the notion of “software independence” in voting systems Ronald L. Rivest John P. Wack Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, MA 02139 [email protected] National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Information Technology Laboratory Gaithersburg, MD 20899 [email protected] DRAFT Version July 28, 2006 Abstract. This paper defines and explores the notion of “software in- dependence” in voting systems: A voting system is software-independent if an undetected change or error in its software cannot cause an undetectable change or error in an election outcome. We propose that software independent voting systems should be pre- ferred, and software-dependent voting systems should be avoided. VVPAT and some cryptographically-based voting systems are software-independent. Variations and implications of this definition are explored. This white paper is also for discussion by the Technical Guidelines Devel- opment Committee (TGDC) in its development of the Voluntary Voting System Guidelines (VVSG) of 2007. 1 Introduction The main purpose of this paper is to introduce and carefully define the ter- minology of “software-independent” and “software-dependent” voting systems, and to discuss their properties. This paper is definitional in character; there are no “results” as such. The contribution is to help provide crisp terminology for discussing voting systems and some recommendations for its usage in the VVSG 2007, currently under development by NIST and the TGDC. This paper starts by describing the problem that software-independence ad- dresses: complex and difficult-to-test software in voting systems. It then defines what constitutes a software-independent approach to voting system design. -

Cost of Counting the Vote

Cost of Counting the Vote The Price of Upgrading Voting Systems in 43 U.S. Counties By Aquene Freechild and Hamdi Soysal, Public Citizen’s Democracy Is For People Campaign May 31, 2018 - Amid serious concerns about whether our elections are secure from hackers and computer error, many state and local governments are looking to replace out-of-date paperless voting systems with paper ballot and electronic scanner systems. Pricing of voting equipment is often opaque, and in many cases, prices are negotiated on a local level. To bring some much-needed clarity to the issue, this report examines how much 43 county governments in 10 states paid for voting equipment. With this information in hand, local election officials and citizens can make the most of limited election equipment dollars. The states are: California, Florida, Iowa, Kentucky, Minnesota, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Texas and Virginia. Our key finding: While most precinct ballot scanners cost around $5,000 to $6,000, some counties have been able to negotiate more favorable pricing. However, a few counties paid a much higher than average price for their equipment. Our key conclusion: It’s important that counties band together or engage state authorities where appropriate to negotiate prices and get the best contract terms for voting equipment. Leasing equipment is an option for county officials to address the security threats quickly without committing to buying new systems on a short time frame. Limited Federal Funding In the 2018 federal spending bill passed by Congress in March 2018, lawmakers made $380 million in election security funding available to states for replacing paperless voting systems, implementing post-election audits and securing election databases. -

The New Jersey Voting-Machine Lawsuit and the AVC Advantage DRE Voting Machine

The New Jersey Voting-machine Lawsuit and the AVC Advantage DRE Voting Machine Andrew W. Appel∗ Maia Ginsburg Harri Hursti Brian W. Kernighan Princeton University Princeton University Princeton University Christopher D. Richards Gang Tan Penny Venetis Princeton University Lehigh University Rutgers School of Law – Newark Abstract As a result of a public-interest lawsuit, by Court order we were able to study, for one month, the hardware and source code of the Sequoia AVC Advantage direct-recording electronic voting machine, which is used throughout New Jersey (and Louisiana), and the Court has permitted us to publicly describe almost everything that we were able to learn. In short, these machines are vulnerable to a wide variety of attacks on the voting process. It would not be in the slightest difficult for a moderately determined group or individual to mount a vote-stealing attack that would be successful and undetectable. 1 Litigation and legislation in New Jersey In October 2004 a group of public-interest plaintiffs, represented by Professor Penny Venetis of the Rutgers Law School, sued the State of New Jersey (in NJ Superior Court) over the State’s use of direct-recording electronic (DRE) voting machines in New Jersey. By 2004, most of New Jersey’s counties had adopted the Sequoia AVC Advantage full-face DRE. Currently 18 out of New Jersey’s 21 counties use this DRE. The plaintiffs argued that the use of DRE voting machines is illegal and unconstitutional: illegal, because they violate New Jersey election laws requiring that all votes be counted accurately and that voting machines be thoroughly tested, accurate, and reliable; and unconstitutional, because they violate the New Jersey constitution’s requirement that all votes count.1 The plaintiffs argued that one cannot trust a paperless DRE machine to count the vote. -

Supreme Court of the United States ______

No. 19-1399 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States ______________________________ SHELBY ADVOCATES FOR VALID ELECTIONS, ET AL., Petitioners, v. TRE HARGETT, ET AL. Respondents. ______________________________ On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit ______________________________ BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE INDIVIDUAL ELECTION SECURITY EXPERTS IN SUPPORT OF CERTIORARI ______________________________ Courtney Hostetler John D. Graubert Ronald Fein Counsel of Record John Bonifaz Megan C. Keenan Ben Clements Ryan Miller FREE SPEECH FOR PEOPLE Jeremy Patashnik 1320 Centre St. #405 COVINGTON & BURLING LLP Newton, MA 02459 One CityCenter (617) 249-3015 850 Tenth Street, NW Washington, DC 20001 [email protected] (202) 662-6000 July 22, 2020 Counsel for Amici Curiae i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ....................................... ii INTERESTS OF AMICI CURIAE .............................. 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ..................................... 2 ARGUMENT ............................................................... 4 I. ABSENT IMMEDIATE REVIEW, VOTING MACHINES IN SHELBY COUNTY WILL CONTINUE TO CAUSE FLAWED ELECTIONS. ...................................... 4 A. The Voting Machines At Issue Are Fundamentally Deficient. ............................5 B. The Voting Machines At Issue Cannot Be Reliably Audited. .................................. 12 C. As a Result of the Sixth Circuit’s Ruling, the Voting Machines At Issue Will Continue To Harm Voters. ................. 15 II. THE SIXTH CIRCUIT’S DECISION CONFLICTS WITH ELEVENTH CIRCUIT PRECEDENT PERMITTING PLAINTIFFS TO CHALLENGE SIMILAR HARMS TO THEIR VOTING RIGHTS. ........... 17 CONCLUSION .......................................................... 27 APPENDIX: List of Individual Election Security Experts ............ 1a ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Page(s) Cases Andrade v. NAACP of Austin, 345 S.W.3d 1 (Tex. 2011) ..................................... 20 City of Los Angeles v. Lyons, 461 U.S. 95 (1983) ............................................... -

Election Fraud Facts & Details

Election Fraud Facts & Details Supporting Files for all items listed can be found at the following URL: https://ufile.io/by3q159v 1 FOREIGN INFLUENCE & NATIONAL SECURITY CONCERNS IN US ELECTIONS 1.1 The core software utilized by Dominion, the 2nd largest US voting machine vendor, originates from intellectual property of Smartmatic; a company that was founded in communist Venezuala with links to Chavez. A. Smartmatic Ties to Hugo Chávez Warned About in 2006 B. SmartMatic Sells Sequoia Voting Systems to US Holding Company After CFIUS Probe C. Sequoia Admits that while they can change the source code (e.g. Software), Smartmatic still owns the intellectual property of the software. D. Dominion Buys Sequoia from Smartmatic and Diebold from ES&S 1.2 ES&S, Dominion, and Hart Intercivic represent 92% of voting machine market and have a long history of significant security vulnerabilities that could be exploited by a nation state in ways that would be difficult to detect. E. Map - Voting Machine Usage in the US F. Defcon 27 - Voting Machine Hacking Village - Vulnerablity Report G. Defcon 26 - Voting Machine Hacking Village - Vulnerablity Report.pdf H. History of ES&S and Diebold (Now Dominion) Vulnerabilities and Voting Inconsistiencies I. Antrim-Michigan-Forensics-Report-121320-v2-Redacted 1.3 An affidavit and scholarly statistical paper attest to Smartmatic rigging Venezualian elections. Smartmatic has also been accused of rigging elections in the Philippines and India J. Venezuala Smartmatic Affidavit K. Statistical Science - 2011 - Volume 26 - Number 4 - Analysis of the 2004 Venezuala Referendum - Official Results Verses the Petition Signatures L. Smartmatic Voting Technology Firm Linked to Alleged Fraud in Elections in Philippines, Venezuela M. -

Security Evaluation of ES&S Voting Machines and Election

Security Evaluation of ES&S Voting Machines and Election Management System Adam Aviv Pavol Cernˇ y´ Sandy Clark Eric Cronin Gaurav Shah Micah Sherr Matt Blaze faviv,cernyp,saender,ecronin,gauravsh,msherr,[email protected] Department of Computer and Information Science University of Pennsylvania Abstract EVEREST was the first major study of ES&S voting sys- tems, despite the system’s popularity (ES&S claims to be This paper summarizes a security analysis of the DRE the world’s largest e-voting systems vendor [1], support- and optical scan voting systems manufactured by Election ing more than 67 million voter registrations with 97,000 Systems and Software (ES&S), as used in Ohio (and many touchscreen voting machines installed in 20 states and other jurisdictions inside and outside the US). We found 30,000 optical ballot readers present in 43 states [4]), and numerous exploitable vulnerabilities in nearly every com- only the second comprehensive study that examined all ponent of the ES&S system. These vulnerabilities enable components – from backend registration systems to fron- attacks that could alter or forge precinct results, install tend ballot casting – of any electronic voting system. In a corrupt firmware, and erase audit records. Our analysis ten week period, our seven-member team was tasked with focused on architectural issues in which the interactions analyzing the nearly 670,000 lines of source code that between various software and hardware modules leads to comprise the ES&S system, encompassing twelve pro- systemic vulnerabilities that do not appear to be easily gramming languages and five hardware platforms1. -

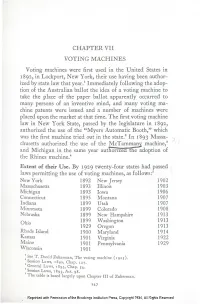

Chapter Vii Voting Machines

CHAPTER VII VOTING MACHINES Voting machines were first used in the United States in 1892, in Lockport, New York, their use having been author- ized by state law that year.! Immediately following the adop- tion of the Australian ballot the idea of a voting machine to take the place of the paper ballot apparently occurred to many persons of an inventive mind, and many voting ma- chine patents were issued and a number of machines were placed upon the market at that time. The first voting m~chine law in New York State, passed by the legislature in 1892, authorized the use of the "Myers Automatic Booth," which was the first machine tried out in the state.2 In 1893 Massa- ~. chusetts authorized the use of the McTamma~ machine,3 " and Michigan in the same year authorIzed the adoption of the. Rhines machine.4 Extent of their Use. By 1929 twenty-four states had passed \ laws permitting the use of voting machines, as follows:5 New York 1892 New Jersey 1902 Massachusetts 1893 Illinois 1903 Michigan 1893 Iowa 1906 Connecticut 1895 Montana 1907 Indiana 1899 Utah 1907 Minnesota 1899 Colorado 1908 Nebraska 1899 New Hampshire 1913 1913 Ohio 1899 Washington 1929 Oregon 1913 Rhode Island 1900 Maryland 1914 Ka~sas 1901 Virginia 1922 MaIne 1901 Pennsylvania 1929 Wisconsin 1901 1 SeeT. David Zukerman, The voting machine (1925). 2 Session Laws, 1892, Chap. 127. 3 General Laws, 1893, Chap. 54. Session Laws, 1893, Act. 98. The table is based largely upon Chapter III of Zukerman. 247 Reprinted with Permission of the Brookings Institution Press, Copyright 1934, All Rights Reserved 248 ELECTION ADMINISTRATION The first large city to try voting machines was Rochester, New York, in 1896. -

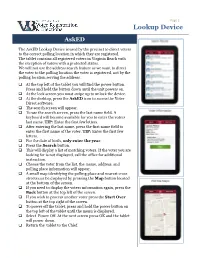

Lookup Device

Page 1 Lookup Device AskED The AskED Lookup Device is used by the precinct to direct voters to the correct polling location in which they are registered. The tablet contains all registered voters in Virginia Beach with the exception of voters with a protected status. We will not use the address search feature as we want to direct the voter to the polling location the voter is registered, not by the polling location serving the address. At the top left of the tablet you will find the power button. Press and hold the button down until the unit powers on. At the lock screen you must swipe up to unlock the device. At the desktop, press the AskED icon to access the Voter Direct software. The search screen will appear. To use the search screen, press the last name field. A keyboard will become available for you to enter the voters last name. TIP: Enter the first few letters. After entering the last name, press the first name field to enter the first name of the voter. TIP: Enter the first few letters. For the date of birth, only enter the year. Press the Search button. This will display a list of matching voters. If the voter you are looking for is not displayed, call the office for additional instruction. Choose the voter from the list, the name, address, and polling place information will appear. A small map identifying the polling place and nearest cross streets can be displayed by pressing the Map button located at the bottom of the screen. -

Voting Equipment and Procedures on Trial

From quill to touch screen: A US history of ballot-casting 1770s Balloting replaces a show of Voting hands or voice votes. Voters write out names of their candidates in longhand, and give their ballots to an election judge. 1850s Political parties disperse Equipment preprinted lists of candidates, enabling the illiterate to vote. The ballot becomes a long strip of paper, like a railroad ticket. 1869 Thomas Edison receives a patent for his invention of the and voting machine, intended for counting congressional votes. 1888 Massachusetts prints a ballot, at public expense, listing names of all candidates nominated Procedures and their party affiliation. Most states adopt this landmark improvement within eight years. 1892 A lever-operated voting machine is first used at a Lockport, N.Y., town meeting. on Trial Similar machines are still in use today. 1964 A punch-card ballot is introduced in two counties in Georgia. Almost 4 in 10 voters used punch cards in the 1996 presidential election. 1990s Michigan is the first to switch to' optical scanning, used for decades in standardized testing. One-quarter of voters used the technology in the 1996 election. 2000 A storm erupts over Florida's punch-card ballots and Palm Beach County's "butterfly ballot" in the presidential election. 2002 New federal law authorizes $3.9 billion over three years to help states upgrade voting technologies and phase out punch cards and lever machines. Georgia is the first state to use DRE touch-screen technology exclusively. Sources: Federal Elections Commission; "Elections A to Z," CQ, 2003; International Encyclopedia of Elections, CQ Press, 2000; League of Women Voters. -

Informational Pamphlet for Election Day Voting

Informational Pamphlet for Election Day Voting Prepared and Distributed by: Secretary of State Approved by: Attorney General, Pursuant to La R.S. 18:421 Disposition: Return Pamphlet in the Green Canvas Bag IP-Elec Day (Rev. 01/20) Informational Pamphlet for Election Day Voting Table of Contents 1.01: Emergency Procedures ................................................................................................. 1 1.02: Before the Election ........................................................................................................ 1 1.03: During the Election ........................................................................................................ 1 1.04: After the Election ........................................................................................................... 1 2.01: Secretary of State .......................................................................................................... 2 2.02: Parish Contacts ............................................................................................................. 2 3.01: Voting Hours .................................................................................................................. 4 3.02: Deputy Custodian Responsibilities ................................................................................. 4 Key Envelope A .............................................................................................. 4 List or Supplemental List Envelope (L-SL) .....................................................