Daniel Allen 12/2/14 MCS 100 Leonid Pekelis the Single to Right Field

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Bayesian Approach to In-Game Win Probability in Soccer

A Bayesian Approach to In-Game Win Probability in Soccer Pieter Robberechts Jan Van Haaren Jesse Davis [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] KU Leuven, Dept. of Computer KU Leuven, Dept. of Computer KU Leuven, Dept. of Computer Science; Leuven.AI Science; Leuven.AI Science; Leuven.AI B-3000 Leuven, Belgium B-3000 Leuven, Belgium B-3000 Leuven, Belgium Premier League - 2011/12 3 : 2 1:0 1:1 QPR 1:2 2:2 3:2 100% City wins 80% 60% Draw 40% 20% QPR wins 15 30 HT 60 75 90 min Figure 1: In-game win probabilities for the game between Manchester City and Queens Park Rangers (QPR) on the final day of the 2011/12 Premier League season. ABSTRACT demonstrates that our framework provides well-calibrated proba- In-game win probability models, which provide a sports team’s bilities. Furthermore, two use cases show its ability to enhance fan likelihood of winning at each point in a game based on historical experience and to evaluate performance in crucial game situations. observations, are becoming increasingly popular. In baseball, bas- ketball and American football, they have become important tools CCS CONCEPTS to enhance fan experience, to evaluate in-game decision-making, • Mathematics of computing ! Probabilistic inference prob- and to inform coaching decisions. While equally relevant in soccer, lems; Variational methods; • Computing methodologies ! Ma- the adoption of these models is held back by technical challenges chine learning; • Information systems ! Data mining. arising from the low-scoring nature of the sport. In this paper, we introduce an in-game win probability model for KEYWORDS soccer that addresses the shortcomings of existing models. -

Repeal of Baseball's Longstanding Antitrust Exemption: Did Congress Strike out Again?

Repeal of Baseball's Longstanding Antitrust Exemption: Did Congress Strike out Again? INTRODUCrION "Baseball is everybody's business."' We have just witnessed the conclusion of perhaps the greatest baseball season in the history of the game. Not one, but two men broke the "unbreakable" record of sixty-one home-runs set by New York Yankee great Roger Maris in 1961;2 four men hit over fifty home-runs, a number that had only been surpassed fifteen times in the past fifty-six years,3 while thirty-three players hit over thirty home runs;4 Barry Bonds became the only player to record 400 home-runs and 400 stolen bases in a career;5 and Alex Rodriguez, a twenty-three-year-old shortstop, joined Bonds and Jose Canseco as one of only three men to have recorded forty home-runs and forty stolen bases in a 6 single season. This was not only an offensive explosion either. A twenty- year-old struck out twenty batters in a game, the record for a nine inning 7 game; a perfect game was pitched;' and Roger Clemens of the Toronto Blue Jays won his unprecedented fifth Cy Young award.9 Also, the Yankees won 1. Flood v. Kuhn, 309 F. Supp. 793, 797 (S.D.N.Y. 1970). 2. Mark McGwire hit 70 home runs and Sammy Sosa hit 66. Frederick C. Klein, There Was More to the Baseball Season Than McGwire, WALL ST. J., Oct. 2, 1998, at W8. 3. McGwire, Sosa, Ken Griffey Jr., and Greg Vaughn did this for the St. -

Why Did Cleveland Indians Sign Mike Napoli Instead of Pedro Alvarez?

Why did Cleveland Indians sign Mike Napoli instead of Pedro Alvarez? Hey, Hoynsie Paul Hoynes, cleveland.com CLEVELAND, Ohio – Do you have a question that you'd like to have answered in Hey, Hoynsie? Submit it here or Tweet him at @hoynsie. Hey, Hoynsie: Why did the Indians sign Mike Napoli, 34, for one year to play first base when Pedro Alvarez, 27, was available? Did management know Alvarez hit 27 home runs last season? -- Jimmy Garst, Roanoke, Va. Hey, Jimmy: The Indians did show interest in Alvarez, who was non-tendered by the Pirates and became a free agent. I think a couple of things probably came into play: No. 1, Alvarez was more expensive than the $7 million deal the Indians agreed to with Napoli. No. 2, the Indians felt Napoli helped them two ways – he gave their offense needed pop from the right side of the plate and he improved their defense. Napoli – whose deal should soon be made official – allows the Indians to move Carlos Santana to DH while he will get most of the time at first base. There is no doubt about Alvarez's power, but he made 23 errors at first base last season. I think the Indians preferred Napoli, considering the cost, at first and Santana at DH instead of Santana at first and Alvarez at DH. Hey, Hoynsie: The Reds seem interested in moving outfielder Jay Bruce. Is the Tribe done with its outfield or would it be interested in a guy who is as streaky hitter as there is, but definitely has pop? – Carl Neifer, Cincinnati. -

NCAA Division I Baseball Records

Division I Baseball Records Individual Records .................................................................. 2 Individual Leaders .................................................................. 4 Annual Individual Champions .......................................... 14 Team Records ........................................................................... 22 Team Leaders ............................................................................ 24 Annual Team Champions .................................................... 32 All-Time Winningest Teams ................................................ 38 Collegiate Baseball Division I Final Polls ....................... 42 Baseball America Division I Final Polls ........................... 45 USA Today Baseball Weekly/ESPN/ American Baseball Coaches Association Division I Final Polls ............................................................ 46 National Collegiate Baseball Writers Association Division I Final Polls ............................................................ 48 Statistical Trends ...................................................................... 49 No-Hitters and Perfect Games by Year .......................... 50 2 NCAA BASEBALL DIVISION I RECORDS THROUGH 2011 Official NCAA Division I baseball records began Season Career with the 1957 season and are based on informa- 39—Jason Krizan, Dallas Baptist, 2011 (62 games) 346—Jeff Ledbetter, Florida St., 1979-82 (262 games) tion submitted to the NCAA statistics service by Career RUNS BATTED IN PER GAME institutions -

Download Preview

DETROIT TIGERS’ 4 GREATEST HITTERS Table of CONTENTS Contents Warm-Up, with a Side of Dedications ....................................................... 1 The Ty Cobb Birthplace Pilgrimage ......................................................... 9 1 Out of the Blocks—Into the Bleachers .............................................. 19 2 Quadruple Crown—Four’s Company, Five’s a Multitude ..................... 29 [Gates] Brown vs. Hot Dog .......................................................................................... 30 Prince Fielder Fields Macho Nacho ............................................................................. 30 Dangerfield Dangers .................................................................................................... 31 #1 Latino Hitters, Bar None ........................................................................................ 32 3 Hitting Prof Ted Williams, and the MACHO-METER ......................... 39 The MACHO-METER ..................................................................... 40 4 Miguel Cabrera, Knothole Kids, and the World’s Prettiest Girls ........... 47 Ty Cobb and the Presidential Passing Lane ................................................................. 49 The First Hammerin’ Hank—The Bronx’s Hank Greenberg ..................................... 50 Baseball and Heightism ............................................................................................... 53 One Amazing Baseball Record That Will Never Be Broken ...................................... -

December, 2016

By the Numbers Volume 26, Number 2 The Newsletter of the SABR Statistical Analysis Committee December, 2016 Review Academic Research: Three Papers Charlie Pavitt The author reviews three recent academic papers: one investigating the effect of the military draft on the timing of the emergence of young baseball players, another investigating pitch selection over the course of a game, and a third modeling pickoff throws using game theory. I haven’t found any truly outstanding contributions in the attenuated in the last half of careers. It was most evident at the academic literature of late, but here are three I found of some highest production levels; the top ten rWARs and all six Hall of interest. Famers from those birth years were all born on “non-draft days.” Mange, Brennan and David C. Phillips (2016), As some potential players below the “magic number” did not Career interruption and productivity: Evidence serve due to student deferments (among other reasons), and some potential players above the figure did serve as volunteers, these from major league baseball during the figures likely underestimate the actual differences between those Vietnam War who did and did not era , Journal of actually serve. The Human Capital, authors presented Vol. 10, No. 2, In this issue data suggesting that the main reason for pp. 159-185 Academic Research: Three Papers ............................Charlie Pavitt ............................1 this effect may be a World Series Pinch Runners, 1990-2015...................Samuel Anthony........................3 greater likelihood of Mange and Phillips Pitcher Batting Eighth ...............................................Pete Palmer ...............................9 potential players conducted a study of Two Strategies: A Story of Change............................Don Coffin ..............................11 opting for four-year interruptions caused by college rather than draft status during the The previous issue of this publication was March, 2016 (Volume 26, Number 1). -

NLDS Notes GM 4.Indd

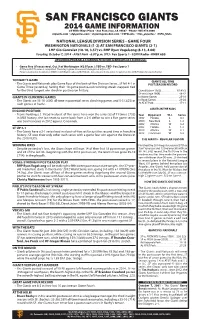

SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS 2014 GAME INFORMATION 24 Willie Mays Plaza •San Francisco, CA 94107 •Phone: 415-972-2000 sfgiants.com •sfgigantes.com •sfgiantspressbox.com •@SFGiants •@los_gigantes• @SFG_Stats NATIONAL LEAGUE DIVISION SERIES - GAME FOUR WASHINGTON NATIONALS (1-2) AT SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS (2-1) LHP Gio Gonzalez (10-10, 3.57) vs. RHP Ryan Vogelsong (8-13, 4.00) Tuesday, October 7, 2014 • AT&T Park • 6:07 p.m. (PT) • Fox Sports 1 • ESPN Radio • KNBR 680 UPCOMING PROBABLE STARTING PITCHERS & BROADCAST SCHEDULE: • Game Five (if necessary), Oct. 9 at Washington (#2:07p.m.): TBD vs. TBD- Fox Sports 1 # If the LAD/STL series is completed, Thursday's game time would change to 5:37p.m. PT Please note all games broadcast on KNBR 680 AM (English radio) and ESPN Radio. All postseason home games broadcast on 860 AM ESPN Deportes (Spanish radio). TONIGHT'S GAME GIANTS ALL-TIME • The Giants and Nationals play Game Four of this best-of- ve Division Series...SF fell 4-1 in POSTSEASON RECORD Game Three yesterday, having their 10-game postseason winning streak snapped, tied for the third-longest win streak in postseason history. Overall (since 1900) . 87-83-2 SF-era (since 1958) . .48-42 GIANTS IN CLINCHING GAMES In Home Games . .25-18 • The Giants are 15-10 (.600) all-time in potential series clinching games and 5-3 (.625) in In Road Games. .23-24 such games at home. At AT&T Park . .17-11 GIANTS IN THE NLDS IN GOOD POSITION • Teams holding a 2-1 lead in a best-of- ve series have won the series 52 of 71 times (.732) Year Opponent W-L Series in MLB history...the last team to come back from a 2-0 de cit to win a ve game series 1997 Florida L 0-3 was San Francisco in 2012 against Cincinnati. -

Teen Stabbing Questions Still Unanswered What Motivated 14-Year-Old Boy to Attack Family?

Save $86.25 with coupons in today’s paper Penn State holds The Kirby at 30 off late Honoring the Center’s charge rich history and its to beat Temple impact on the region SPORTS • 1C SPECIAL SECTION Sunday, September 18, 2016 BREAKING NEWS AT TIMESLEADER.COM '365/=[+<</M /88=C6@+83+sǍL Teen stabbing questions still unanswered What motivated 14-year-old boy to attack family? By Bill O’Boyle Sinoracki in the chest, causing Sinoracki’s wife, Bobbi Jo, 36, ,9,9C6/Ľ>37/=6/+./<L-97 his death. and the couple’s 17-year-old Investigators say Hocken- daughter. KINGSTON TWP. — Specu- berry, 14, of 145 S. Lehigh A preliminary hearing lation has been rampant since St. — located adjacent to the for Hockenberry, originally last Sunday when a 14-year-old Sinoracki home — entered 7 scheduled for Sept. 22, has boy entered his neighbors’ Orchard St. and stabbed three been continued at the request house in the middle of the day members of the Sinoracki fam- of his attorney, Frank Nocito. and stabbed three people, kill- According to the office of ing one. ily. Hockenberry is charged Magisterial District Justice Everyone connected to the James Tupper and Kingston case and the general public with homicide, aggravated assault, simple assault, reck- Township Police Chief Michael have been wondering what Moravec, the hearing will be lessly endangering another Photo courtesy of GoFundMe could have motivated the held at 9:30 a.m. Nov. 7 at person and burglary in connec- In this photo taken from the GoFundMe account page set up for the Sinoracki accused, Zachary Hocken- Tupper’s office, 11 Carverton family, David Sinoracki is shown with his wife, Bobbi Jo, and their three children, berry, to walk into a home on tion with the death of David Megan 17; Madison, 14; and David Jr., 11. -

Oakland Raiders 1

NNNorthN America’s Charity Fundraising “One Stop Shop” BW Unlimited is proud to provide this incredible list of hand signed Sports Memorabilia from around the U.S. All of these items come complete with a Certificate of Authenticity (COA) from a 3rd Party Authenticator. From Signed Full Size Helmets, Jersey’s, Balls and Photo’s …you can find everything you could possibly ever want. Please keep in mind that our vast inventory constantly changes and each item is subject to availability. When speaking to your Charity Fundraising Representative, let them know which items you would like in your next Charity Fundraising Event: Hand Signed Sports Memorabilia California Angels 1. Nolan Ryan Signed California Angels Jersey 7 No Hitters PSA/DNA (BWU001IS) $439 2. Nolan Ryan Signed California Angels 16x20 Photo SI & Ryan Holo (BWU001IS) $210 3. Nolan Ryan California Angels & Amos Otis Kansas City Royals Autographed 8x10 Photo -Pitching- (BWU001EPA) $172 4. Autographed Don Baylor Baseball Inscribed "MVP 1979" (BWU001EPA) $124 5. Rod Carew California Angels Autographed White Majestic Jersey (BWU001EPA) $304 6. Wally Joyner Autographed MLB Baseball (BWU001EPA) $148 7. Wally Joyner Autographed Big Stick Bat With His Name Printed On The Bat (BWU001EPA) $176 8. Wally Joyner California Angels Autographed Majestic Jersey (BWU001EPA) $280 9. Mike Witt Autographed MLB Baseball Inscribed "PG 9/30/84" (BWU001EPA) $148 L.A. Dodgers 1. Fernando Valenzuela Signed Dodgers Jersey (BWU001IS) $300 2. Autographed Fernando Valenzuela Baseball (BWU001EPA) $232 3. Autographed Fernando Valenzuela Los Angeles Dodgers White Majestic Jersey (BWU001EPA) $388 4. Duke Snider signed baseball (BWU001IS) $200 5. Tommy Lasorda signed jersey dodgers (BWU001IS) $325 6. -

Probable Starting Pitchers 31-31, Home 15-16, Road 16-15

NOTES Great American Ball Park • 100 Joe Nuxhall Way • Cincinnati, OH 45202 • @Reds • @RedsPR • @RedlegsJapan • reds.com 31-31, HOME 15-16, ROAD 16-15 PROBABLE STARTING PITCHERS Sunday, June 13, 2021 Sun vs Col: RHP Tony Santillan (ML debut) vs RHP Antonio Senzatela (2-6, 4.62) 700 wlw, bsoh, 1:10et Mon at Mil: RHP Vladimir Gutierrez (2-1, 2.65) vs LHP Eric Lauer (1-2, 4.82) 700 wlw, bsoh, 8:10et Great American Ball Park Tue at Mil: RHP Luis Castillo (2-9, 6.47) vs LHP Brett Anderson (2-4, 4.99) 700 wlw, bsoh, 8:10et Wed at Mil: RHP Tyler Mahle (6-2, 3.56) vs RHP Freddy Peralta (6-1, 2.25) 700 wlw, bsoh, 2:10et • • • • • • • • • • Thu at SD: LHP Wade Miley (6-4, 2.92) vs TBD 700 wlw, bsoh, 10:10et CINCINNATI REDS (31-31) vs Fri at SD: RHP Tony Santillan vs TBD 700 wlw, bsoh, 10:10et Sat at SD: RHP Vladimir Gutierrez vs TBD 700 wlw, FOX, 7:15et COLORADO ROCKIES (25-40) Sun at SD: RHP Luis Castillo vs TBD 700 wlw, bsoh, mlbn, 4:10et TODAY'S GAME: Is Game 3 (2-0) of a 3-game series vs Shelby Cravens' ALL-TIME HITS, REDS CAREER REGULAR SEASON RECORD VS ROCKIES Rockies and Game 6 (3-2) of a 6-game homestand that included a 2-1 1. Pete Rose ..................................... 3,358 All-Time Since 1993: ....................................... 105-108 series loss to the Brewers...tomorrow night at American Family Field, 2. Barry Larkin ................................... 2,340 At Riverfront/Cinergy Field: ................................. -

UPCOMING SCHEDULE and PROBABLE STARTING PITCHERS DATE OPPONENT TIME TV ORIOLES STARTER OPPONENT STARTER June 12 at Tampa Bay 4:10 P.M

FRIDAY, JUNE 11, 2021 • GAME #62 • ROAD GAME #30 BALTIMORE ORIOLES (22-39) at TAMPA BAY RAYS (39-24) LHP Keegan Akin (0-0, 3.60) vs. LHP Ryan Yarbrough (3-3, 3.95) O’s SEASON BREAKDOWN KING OF THE CASTLE: INF/OF Ryan Mountcastle has driven in at least one run in eight- HITTING IT OFF Overall 22-39 straight games, the longest streak in the majors this season and the longest streak by a rookie American League Hit Leaders: Home 11-21 in club history (since 1954)...He is the first Oriole with an eight-game RBI streak since Anthony No. 1) CEDRIC MULLINS, BAL 76 hits Road 11-18 Santander did so from August 6-14, 2020; club record is 11-straight by Doug DeCinces (Sep- No. 2) Xander Bogaerts, BOS 73 hits Day 9-18 tember 22, 1978 - April 6, 1979) and the club record for a single-season is 10-straight by Reggie Isiah Kiner-Falefa, TEX 73 hits Night 13-21 Jackson (July 11-23, 1976)...The MLB record for consecutive games with an RBI by a rookie is No. 4) Vladimir Guerrero, Jr., TOR 70 hits Current Streak L1 10...Mountcastle has hit safely in each of these eight games, slashing .394/.412/.848 (13-for-33) Yuli Gurriel, HOU 70 hits Last 5 Games 3-2 with three doubles, four home runs, seven runs scored, and 12 RBI. Marcus Semien, TOR 70 hits Last 10 Games 5-5 Mountcastle’s eight-game hitting streak is the longest of his career and tied for the April 12-14 fourth-longest active hitting streak in the American League. -

Learning Unethical Practices from a Co-Worker: the Peer Effect of Jose Canseco

IZA DP No. 3328 Learning Unethical Practices from a Co-worker: The Peer Effect of Jose Canseco Eric D. Gould Todd R. Kaplan DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES DISCUSSION PAPER January 2008 Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor Learning Unethical Practices from a Co-worker: The Peer Effect of Jose Canseco Eric D. Gould Hebrew University, Shalem Center, CEPR, CREAM and IZA Todd R. Kaplan Haifa University and University of Exeter Discussion Paper No. 3328 January 2008 IZA P.O. Box 7240 53072 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-3894-0 Fax: +49-228-3894-180 E-mail: [email protected] Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) in Bonn is a local and virtual international research center and a place of communication between science, politics and business. IZA is an independent nonprofit organization supported by Deutsche Post World Net. The center is associated with the University of Bonn and offers a stimulating research environment through its international network, workshops and conferences, data service, project support, research visits and doctoral program. IZA engages in (i) original and internationally competitive research in all fields of labor economics, (ii) development of policy concepts, and (iii) dissemination of research results and concepts to the interested public. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character.