Phantasm Elizabeth Kenny Phantasm Elizabeth Kenny Lute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DUNEDIN CONSORT JOHN BUTT SIX Brandenburg Concertos

DUNEDIN CONSORT JOHN BUTT SIX BRANDENBURG CONCERTOS John Butt Director and Harpsichord Cecilia Bernardini Violin Pamela Thorby Recorder David Blackadder Trumpet Alexandra Bellamy Oboe Catherine Latham Recorder Katy Bircher Flute Jane Rogers Viola Alfonso Leal del Ojo Viola Jonathan Manson Violoncello Recorded at Post-production by Perth Concert Hall, Perth, UK Julia Thomas from 7-10 May 2012 Design by Produced and recorded by Gareth Jones and gmtoucari.com Philip Hobbs Photographs by Assistant engineering by David Barbour Robert Cammidge Cover image: The Kermesse, c.1635-38 (oil on panel) by Peter Paul Rubens (Louvre, Paris, France / Giraudon / The Bridgeman Art Library) DISC 1 Brandenburg Concerto No. 1 in F Major, BWV 1046 Concerto 1mo à 2 Corni di Caccia, 3 Hautb: è Bassono, Violino Piccolo concertato, 2 Violini, una Viola è Violoncello col Basso Continuo q […] 4:02 w Adagio 3:44 e Allegro 4:11 r Menuet Trio Polonaise 8:47 Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F Major, BWV 1047 Concerto 2do à 1 Tromba, 1 Flauto, 1 Hautbois, 1 Violino, concertati, è 2 Violini, 1 Viola è Violone in Ripieno col Violoncello è Basso per il Cembalo t […] 4:51 y Andante 3:18 u Allegro assai 2:44 Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 in G Major, BWV 1048 Concerto 3zo a tre Violini, tre Viole, è tre Violoncelli col Basso per il Cembalo i […] 5:30 o Adagio 0:25 a Allegro 4:46 Total Time: 42:44 DISC 2 Brandenburg Concerto No. 4 in G Major, BWV 1049 Concerto 4ta à Violino Principale, due Fiauti d’Echo, due Violini, una Viola è Violone in Ripieno, Violoncello è Continuo q Allegro 6:45 w Andante 3:20 e Presto 4:30 Brandenburg Concerto No. -

John Ward Phantasm

JOHN WARD Fantasies & Verse Anthems PHANTASM Choir of Magdalen College, Oxford JOHN WARD (c.1589–1638) Fantasies & Verse Anthems 1. Fantasia 2 a4 (VDGS 22) 2:13 2. Praise the Lord, O my soul 8:17 3. Fantasia 5 a4 (VDGS 25) 2:49 4. Mount up, my soul 7:04 5. Fantasia 1 a4 (VDGS 21) 2:53 6. Down, caitiff wretch (Part 1) 5:40 7. Prayer is an endless chain (Part 2) 5:27 8. Fantasia 3 a4 (VDGS 23) 2:25 9. How long wilt thou forget me, O Lord 4:51 10. Fantasia 4 a4 (VDGS 24) 3:11 11. Let God arise 6:13 12. Fantasia 6 a4 (VDGS 26) 2:53 13. This is a joyful, happy holy day 5:50 Total Running Time: 60 minutes 2 PHANTASM Laurence Dreyfus Recorded in the director and treble viol Chapel of Magdalen College, Oxford, UK, 6–9 May 2013 Emilia Benjamin Produced by treble and tenor viols Philip Hobbs (fantasies) and Jonathan Manson Adrian Peacock (anthems) tenor viol Engineered by Mikko Perkola Philip Hobbs bass viol Post-production by Julia Thomas with guests Cover image Emily Ashton Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales tenor and bass viols With permission from the President and Fellows of Magdalen College, Oxford Christopher Terepin tenor viol Design by gmtoucari.com Choir of Magdalen College, Oxford directed by Daniel Hyde 3 Fantasies a4 & Verse Anthems In his ambitious and accomplished music for voices and viols, John Ward (c.1589–1638) offers a privileged glimpse of a special moment in English music history. -

HANDEL UNCAGED Cantatas for Alto

HANDEL UNCAGED Cantatas for Alto LAWRENCE ZAZZO countertenor JONATHAN MANSON cello & viola da gamba ANDREW MAGINLEY theorbo & guitar GUILLERMO BRACHETTA harpsichord HANDEL UNCAGED George Frideric Handel (1685–1759) Amore uccellatore, HWV 176/175 Cantatas for Alto 23. Recitative: Vedendo amor [0:39] Udite il mio consiglio, HWV 172 24. Aria: In un folto bosco ombroso [5:28] (Ruspoli version) 25. Recitative: In quel bosco [0:49] Lawrence Zazzo, countertenor 1. Recitative: Udite il mio consiglio [1:29] 26. Aria: Camminando lei pian piano [3:50] Jonathan Manson, cello & viola da gamba 2. Aria: Non le scherzate intorno [4:02] 27. Recitative: Caricò, scaricò [0:34] Andrew Maginley, theorbo & guitar 3. Recitative: Al vederla sovente [1:03] 28. Aria: Rise Eurilla [2:37] 4. Aria: Non esce un guardo mai [4:39] 29. Recitative: Fra tanto [0:15] Guillermo Brachetta, harpsichord 5. Recitative – Arioso: Volea pur dir [2:27] 30. Sonatina in G major, HWV 582 [0:51] Stanco di più soffrire, HWV 167a 6. Recitative: Stanco di più soffrire [1:14] Amore uccellatore, HWV 176/175 7. Aria: Era in sogno almen contento [4:47] 31. Recitative: Non fu gran tempo lieto [0:20] 8. Recitative: Quando mi parve allora [1:07] 32. Aria: Quando meno lo pensai [2:25] 9. Aria: Se più non t’amo [2:23] 33. Recitative: Ella aprendo la gabbia [0:38] 34. Aria: Quivi amor non può venire [1:04] Guillermo Brachetta (after G.F. Handel) 35. Recitative: Voglio che m’entri in tasca [0:28] 10. Improvisation [0:46] 36. Recitative: Amor che per suo servo mi voleva [0:39] Figli del mesto cor, HWV 112 37. -

Carolyn Sampson Elizabeth Kenny Jonathan Manson Laurence Cummings

b0083_WH booklet template.qxd 24/05/2016 07:47 Page 1 Carolyn Sampson Elizabeth Kenny Jonathan Manson Laurence Cummings Come all ye songsters b0083_WH booklet template.qxd 24/05/2016 07:47 Page 2 Carolyn Sampson soprano Elizabeth Kenny lute Jonathan Manson bass viol Laurence Cummings harpsichord Come all ye songsters Recorded live at Wigmore Hall, London, on 17 March 2015 Henry Purcell (1659–1695) 01 Come all ye songsters (from The Fairy Queen Z629, 1692) CS, EK, JM, LC 01.56 02 Sing while we trip it (from The Fairy Queen) CS, EK, JM, LC 00.41 03 A dance of fairies (from The Fairy Queen) EK, JM, LC 00.44 04 Ye gentle spirits of the air (from The Fairy Queen) CS, EK, JM, LC 05.47 Henry Purcell Harpsichord Suite No. 5 in C major (with Jig) Z666 (1696) LC 05.59 05 Prelude 00.43 06 Almand 02.06 07 Corant 01.01 08 Saraband 01.08 09 Jig 00.48 Henry Purcell 10 The cares of lovers (from Timon of Athens Z632, 1695) CS, EK 01.59 11 Fly swift, ye hours Z369 (1691) CS, JM, LC 05.31 12 Not all my torments Z400 (1693) CS, EK, LC 02.47 Giovanni Battista DraGHi (c1640–1708) 13 An Italian Ground EK, JM 03.12 2 b0083_WH booklet template.qxd 24/05/2016 07:47 Page 3 Henry Purcell 14 From rosy bow’rs (from Don Quixote Z578, 1694–5) CS, EK, JM, LC 06.17 15 Let the dreadful Engines of Eternal Will (from Don Quixote) CS, EK, JM, LC 06.52 Music from ‘Princess Anne’s lute book’ 16 Henry Purcell (arr. -

Phantasm Elizabeth Kenny Phantasm Elizabeth Kenny Lute

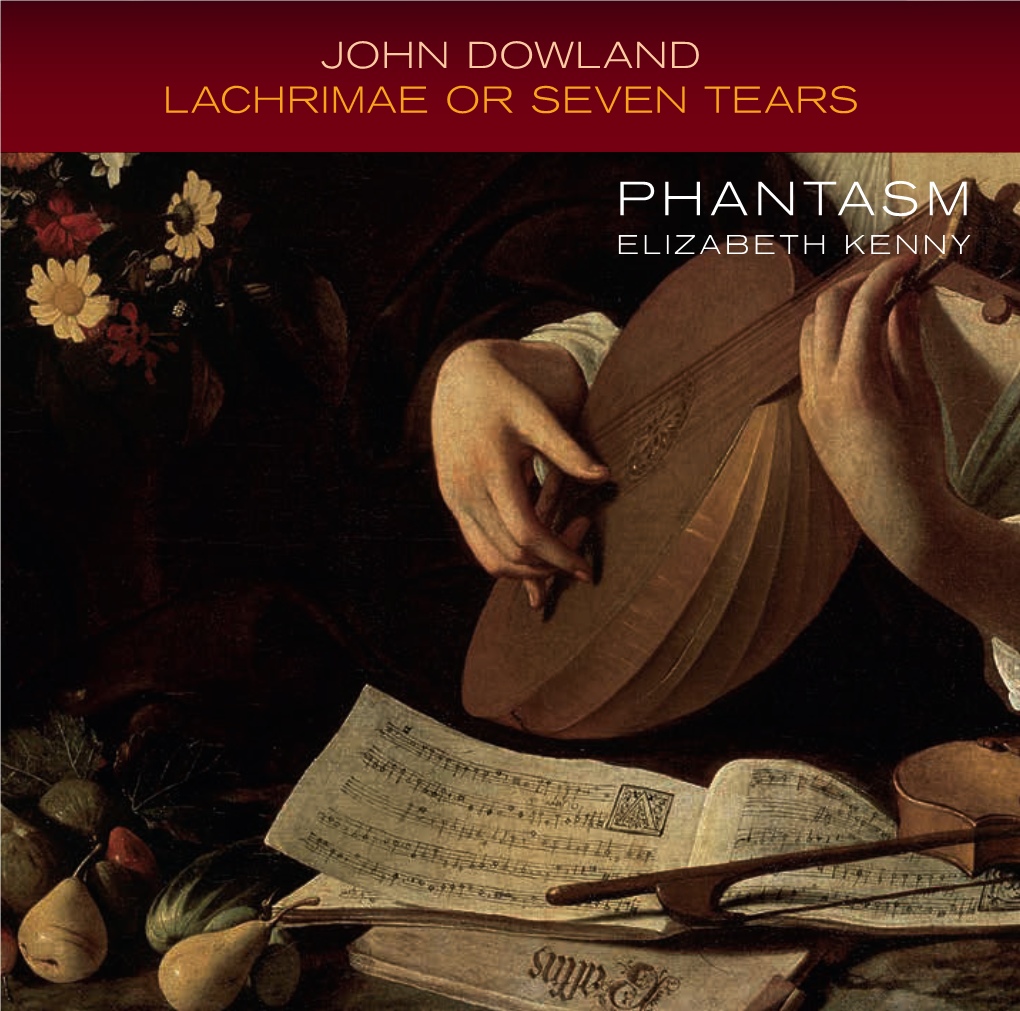

JOHN DOWLAND LACHRIMAE OR SEVEN TEARS PHANTASM ELIZABETH KENNY PHANTASM ELIZABETH KENNY LUTE John Dowland (1563?–1626) Lachrimae or Seven Tears q Lachrimae Antiquae ............................................................................................................................. 4:02 w Lachrimae Antiquae Novae ............................................................................................................ 3:28 e Lachrimae Gementes ......................................................................................................................... 3:36 r Lachrimae Tristes .................................................................................................................................... 3:50 t Lachrimae Coactae ............................................................................................................................... 3:17 y Lachrimae Amantis ............................................................................................................................... 3:56 u Lachrimae Verae ..................................................................................................................................... 4:02 i Mr Nicholas Gryffith his Galliard ................................................................................................ 1:47 o Sir John Souch his Galliard ........................................................................................................... 1:30 a Semper Dowland semper Dolens ............................................................................................ -

7 Jonathan Manson & Steven Devine

Autumn Special Online from 14 September 2020, 8:00pm | Holy Trinity Church, Haddington Jonathan Manson viola da gamba Steven Devine harpsichord Johann Sebastian Bach Viola da Gamba Sonata No. 1 in G Major, BWV 1027 1. Adagio • 2. Allegro ma non tanto • 3. Andante • 4. Allegro moderato Marin Marais Pièces de viole La petite bru – Air gracieux (Book V, 1725) Le badinage (Book IV, 1717) Chaconne (Book V, 1725) Johann Sebastian Bach Viola da Gamba Sonata No. 2 in D Major, BWV 1028 1. Adagio • 2. Allegro • 3. Andante • 4. Allegro Jean-Philippe Rameau L’enharmonique from Suite in G Major, RCT 6 Johann Sebastian Bach Viola da Gamba Sonata No. 3 in G Minor, BWV 1029 1. Vivace • 2. Adagio • 3. Allegro The Lammermuir Festival is a registered charity in Scotland SC049521 Although Johann Sebastian Bach is most highly regarded for his compositional invention and daring originality, he was also something of a musical magpie. A large part of his output was the result of fusions between the different European musical styles prevalent in the first half of the eighteenth century. Bringing together the latest ideas from France and Italy with his thorough grounding in the Lutheran German tradition, Bach was able to generate works that would have sounded incredibly fresh. There is perhaps nowhere in Bach's output where this cross-pollination is more evident than in his three sonatas for viola da gamba and harpsichord. While each of them broadly displays the influence of the French tradition on Bach's approach, he made use of Italian and German formal models that allowed their attractive melodic ideas to be extended into more elaborate musical structures. -

Arcanto Quartet the English Concert

concerts from the library of congress 20 10–20 11 The Friends of Music Fund The Da Capo Fund in the Library of Congress ARCANTO QUARTET THE EHNarryG BicLkeIt,S ArH tisticC DireOctoNr CERT Wednesday, October 13, 2010 Thursday, October 14, 2010 8 o’clock in the evening Coolidge Auditorium Thomas Jefferson Building The FRIENDS OF MUSIC in the Library of Congress was founded in 1928 as a non-profit organization, with Nicholas Longworth, Speaker of the House of Repre- sentatives, as president, and with some members of the former Chamber Music Society of Washington. One of its purposes was to provide for its members “concerts to which the richness of the national music collection will contribute unusual musi - cal significance.” Due to the war, the organization's funds were turned over to the Library of Congress in 1942. The Da Capo Fund in the Library of Congress, established by an anonymous donor, supports concerts, publications, and special projects of both scholarly and general interest, based on items of unique artistic or human appeal in the Music Division collections. The term “Da Capo” is a musical one which means “repeat from the beginning,” indicating that this is a revolving fund—income from its projects goes back into the fund to support additional activities. Q The audiovisual recording equipment in the Coolidge Auditorium was endowed in part by the Ira and Leonore Gershwin Fund in the Library of Congress. Request ASL and ADA accommodations five days in advance of the concert at 202 –707 –6362 or [email protected]. Due to the Library’s security procedures, patrons are strongly urged to arrive thirty minutes before the start of the concert.