David N. Parsons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for South Planning Committee, 24/09/2019 14:00

Shropshire Council Legal and Democratic Services Shirehall Abbey Foregate Shrewsbury SY2 6ND Date: Monday, 16 September 2019 Committee: South Planning Committee Date: Tuesday, 24 September 2019 Time: 2.00 pm Venue: Shrewsbury/Oswestry Room, Shirehall, Abbey Foregate, Shrewsbury, Shropshire, SY2 6ND You are requested to attend the above meeting. The Agenda is attached Claire Porter Director of Legal and Democratic Services (Monitoring Officer) Members of the Committee Substitute Members of the Committee Andy Boddington Roger Evans David Evans Nigel Hartin Simon Harris Christian Lea Nick Hignett Elliott Lynch Richard Huffer Dan Morris Cecilia Motley Kevin Pardy Tony Parsons William Parr Madge Shineton Kevin Turley Robert Tindall Claire Wild David Turner Leslie Winwood Tina Woodward Michael Wood Your Committee Officer is: Linda Jeavons Committee Officer Tel: 01743 257716 Email: [email protected] AGENDA 1 Election of Chairman To elect a Chairman for the ensuing year. 2 Apologies for Absence To receive any apologies for absence. 3 Appointment of Vice-Chairman To appoint a Vice-Chairman for the ensuing year. 4 Minutes To confirm the minutes of the South Planning Committee meeting held on 28 August 2019. TO FOLLOW Contact Linda Jeavons (01743) 257716. 5 Public Question Time To receive any questions or petitions from the public, notice of which has been given in accordance with Procedure Rule 14. The deadline for this meeting is no later than 2.00 pm on Friday, 20 September 2019. 6 Disclosable Pecuniary Interests Members are reminded that they must not participate in the discussion or voting on any matter in which they have a Disclosable Pecuniary Interest and should leave the room prior to the commencement of the debate. -

SHROPSHIRE. [KELLY's FAIDIERS-Continued

650 FAR SHROPSHIRE. [KELLY's FAIDIERS-COntinued. Yardley Matthew Henry, Kinley wick, Griffiths Richard (to Richard Jones Wolley Tbos. S.Clunbory, Clun R.S.O Preston-on-thA-Wea.ldmoors,Wellngtn esq.), Lower Aston, Aston, Church WollsteinLouisEdwd.Arleston, Wellngtn Yardley Richard, Brick Kiln farm, Stoke R.S.O Wood Arthur,Astonpk.Aston,Shrwsbry Aston Eyres, Bridgnortb Hair William (to William Taylor esq.), Wood E.Lynch gal.e,LydburyNth.R.S.O'Yardley Rd.Arksley,Chetton,Bridgnorth Plaish park, Leebotwood, Shrewsbury WoodJohu,Edgton,Aston-on-ClunR.S.O Yardley Thomas, Birchall farm, Middle- Hayden William (to H. D. Cbapman esq. Wood John,Lostford ho.Market Drayton ton Scriven, Bridgnorth J.P. ), Dudleston, Ellesmere Wood Thomas,Dudston,Chirbury R.S.O Yardley William, Coates farm, Middle- Heighway Thomas (to the Rev. Edmund Wood Thomas, Farley, Shrewsbury ton Scriven, Bridgnorth DonaldCarrB.A.).Woolstastn.Shrwsby Wood Thomas, Horton, Wellington Yates Barth. Lawley, Horsehay R.S.O Higley George (to Col. R. T. Lloyd D.L., WoodWm.Ed,<7f.on,Aston-on-Clun R.S.O YatesF. W.Sheinwood,Shineton,Shrwsby J.P. ), Wootton, Oswestry Woodcock Daniel John, New house,Har- Yates G. Hospital street, Much Wen- Hogson Joseph {to Col. H. C. S. Dyer),. ley, Much Wenlock R.S.O lock R.S.O Westhope, Craven Arms R.S.O Woodcock Richard Thomas, Lower Bays- Yates Howard Cecil, Severn hall, Astley Howell William (to F. J. Cobley esq.),. ton, Bayston hill, Shrewsbury Abbotts, Bridgnorth Creamore house, Edstaston, Wem Woodcock Samuel, Churton house, Yeld Edward, Endale, Kimbolton, Hudson Richard (to Thomas Jn. Franks Church Pulverbatch, Shrewsbury Leominster esq.), Lea. -

Corvedale View

CORVEDALE VIEW BROCKTON, MUCH WENLOCK, TF13 6JU A superb conversion of a farm building to a spacious and contemporary home enjoying outstanding views down the Corvedale and towards Brown Clee and set in a generous garden. ACCOMMODATION Entrance Hall | Kitchen / breakfast room | Living area / Dining room | Utility Four bedrooms (three en-suite) | Bathroom | Study | Cloakroom Three bay carport | Driveway | Garden | EPC predicted rating: D Much Wenlock 6 miles, Ludlow 15 miles, Shrewsbury 18 miles, Telford 15 Miles, Wolverhampton 26 miles THE PROPERTY Corvedale View is situated on the edge of the picturesque village of Brockton and is set on a generous plot with the garden adjoining farmland and having far reaching views down the Corvedale towards Brown Clee. Approached of a driveway to the side of More Hall, the property sits within a plot of 0.4 acre and has generous parking to the front of the building where there is also a three-bay car port that is being completed to include scope for an electric car charging point to be installed. The property has been converted in keeping with its history, with big barn-style sliding doors and an edgy rustic theme to the high-spec finish. The property has wooden floors throughout the ground floor, fibre wi-fi and the Living room is wired for five-point surround sound. Entering the property into the light-filled, double-height Entrance Hall opening into a fabulous open-plan Living/Dining area which is flooded with natural light and enjoys a multi-fuel fire and large sliding doors onto the decking. -

Highley Market Town Profile

Highley Market Town Profile Winter 2017/18 1 INFORMATION, INTELLI GENCE & INSIGHT Contents Section Page Introduction 3 Local Politics 5 Demographics 7 Economy 14 Tourism & Leisure 30 Health 32 Housing 35 Education 40 Transport & Infrastructure 42 Community Safety 43 Additional Information 45 2 INFORMATION, INTELLI GENCE & INSIGHT Phone: 0345 678 9000 Email: [email protected] Market Town Profile Highley Highley is a large village located in the east of Shropshire, just seven miles south of Bridgnorth town. Highley is a long settlement which is spread over a mile on the B4555 along the River Severn to the west. Highley began as a rural farming community, including an entry in the Domesday Book as Hughli , named after the lord of the manor. Later the area became a significant area for stone quarrying, which provided some of the stone for Worcester Cathedral. Coal mining began in the area in the Middle Ages but the formation of the Highley Mining Company in 1874 saw the expansion of the village. The mine closed in 1969 and is now home to the Severn Valley Country Park. Area Quick Statistics 637 hectares 1,583 households 3,600 people 5.7 people per hectare 1,653 dwellings 44 is the average age This town profile has been produced by the Information, Intelligence and Insight team of Shropshire Council. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information supplied herein, Shropshire Council cannot be held responsible for any errors or omissions. 3 INFORMATION, INTELLI GENCE & INSIGHT Highley Town Council Area Key Assets The information in this market town is predominantly focussed on the parish council area of Highley. -

![LUDLOW [03Lud]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1832/ludlow-03lud-271832.webp)

LUDLOW [03Lud]

shropshire landscape & visual sensitivity assessment LUDLOW [03lud] 28 11 2018— REVISION 01 CONTENTS SETTLEMENT OVERVIEW . .3 PARCEL A . .4 PARCEL B . 6. PARCEL C . .8 PARCEL D . .10 PARCEL E . 12. PARCEL F . 14. LANDSCAPE SENSITIVITY . .16 VISUAL SENSITIVITY . .17 DESIGN GUIDANCE . 18. ALL MAPPING IN THIS REPORT IS REPRODUCED FROM ORDNANCE SURVEY MATERIAL WITH THE PERMISSION OF ORDNANCE SURVEY ON BEHALF OF HER MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE. © CROWN COPYRIGHT AND DATABASE RIGHTS 2018 ORDNANCE SURVEY 100049049. AERIAL IMAGERY: ESRI, DIGITALGLOBE, GEOEYE, EARTHSTAR GEOGRAPHICS, CNES/AIRBUS DS, USDA, USGS, AEROGRID, IGN, AND THE GIS USER COMMUNITY SHROPSHIRE LANDSCAPE & VISUAL SENSITIVITY ASSESSMENT 03. LUDLOW [03LUD] LOCATION AND DESCRIPTION Ludlow is a medieval market town found some 28 miles south of Shrewsbury . There is a population of over 10,180 and the town is significant in the history of the Welsh Marches . The historic town 03LUD-E centre and 11th century Ludlow Castle 03LUD-D are situated on a cliff above the River Teme, beneath the Clee Hills . There 03LUD-F are almost 500 listed buildings and Ludlow has been described as ‘probably the loveliest town in England ’. For the purposes of this study the settlement has been divided into 6 parcels . ! ! 03LUD-A ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 03LUD-B ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 03LUD-C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Ludlow ! ! ! ! ! 3 SHROPSHIRE LANDSCAPE & VISUAL SENSITIVITY ASSESSMENT LUDLOW A [03LUD-A] LOCATION AND CHARACTER Parcel A is located to the south west of Ludlow and some 3km south west of the Shropshire Hills AONB and within 1km of the Hertfordshire border . Field edges form the parcel boundaries to the west and south, with the B4361 to the east leading into Ludlow . -

RGRG-News-Sum-21July21b-2

RGRG Newsletter * Summer * 21st July 2021 Email news to outgoing Editor [email protected] or Aimee [email protected] Images: D. Agol, E. Anderson, C. Howie, A. Morse, BA & MYS Scholten, RGS-IBG, Unis, Wiki & CC BY-NC => RGS-IBG 2021 London virtual conference, Tues 31 Aug to Fri 3 Sep 2021 (AGM 1.10 pm Wed 1 Sep.) *RGRG sessions 2021 HERE * Also: https://rgrg.co.uk/rgs-with-ibg-international-conference-2020 Chaired by Prof Uma Kothari, on the theme Borders, borderlands and bordering SECTION | CONTENTS (page) 1. Editorial: Thanks – Keep writing! (1) 6. Ewan Anderson on Trees in rural geog (5-6) 2. Megan P-A on Medals & UG winners (1-2) 7. Books: Charles Howie on Richard Baines (7) 3. Philippa Simmonds on CCRI Winter Sch. (2-3) 8. Dorice Agol & Nairobi food vendors (8-9) 4. Aimee Morse on CCRI Summer Sch. (4) 9. Writing for RGRG Newsletter & web (10) 5. Niamh McHugh on PGF Mid-Term (4) 10. RGS-IBG AGM, sessions & abstracts (10-27) 1. Editorial: Editor Dr. Mark Riley, Liverpool, passed the pen to me at Durham Geography in 2009. Over the next 12 years, more colour pix graced articles from Algeria, Brazil, the EU, India, Kenya, Libya, UK, Malaysia, Vietnam, and 2019 Brit-Can-Am-Oz Quad in Vermont, USA. In 2020 RGRG Newsletter migrated to London (rgrg.co.uk/). Its Archive & Bibliography pages need your ongoing input. Now, the infamous newsletter highlights the mostly virtual London conference 30.Aug.-2. Sep.2021. Complete information is on the new RGS-IBG Cisco System: https://event.ac2021.exordo.com/ This issue proudly features Dorice Agol’s stirring tales of food entrepreneurship in Nairobi’s Covid-19-hit informal settlements. -

Held At: Victory Hall, Neen Sollars, DY14 0AL

Ordinary meeting of the Parish Council Milson and Neen Sollars Held at: Victory Hall, Neen Sollars, DY14 0AL Date: 27/11/2017 Time: 19.00 Hrs Summons: Cllr Chris Jones (Chairman) 01584 890486 [email protected] Cllr Steve Painter 01299 832981 [email protected] Cllr Anne Horsley 01299 271225 [email protected] Cllr Mazella Witts-Hewinson 01299 271258 [email protected] Cllr David Jones (Vice Chairman) 01299 271204 [email protected] Tony Price (Clerk to Parish) 01299 271535 [email protected] 1. Apologies: Cllr Chris Jones Holiday 2. Declaration of Pecuniary Interest: None 3. Minutes of Ordinary meeting 18/09/2017. Read and signed as true record. 4. Accounts • Current account balance £11,071.31 • Community Benefit £3,748.00 • Election account £ 451.35 • Note: New 5-year term for small Council Audits has been granted to Mazars 2017/18 to 2021/22. New cost limit for Audits subject to limited assurance review has been increased from 10K to 25K for this period. • Payments for signature. 1. £160.00 Rod Walker ~ Tree Surgeon attended Milson Green. 2. £146.72 Annual SALC affiliation fee. 3. £18.00 Claire Bradley ~ Wreath for Remembrance Neen Sollars. • Proposals for December: £210.46 ~ 2 x Replacement (out of Date) Battery and Pads for Defibrillators. Motion raised MWH Seconded AH £180.00 Training CR+ device (see Agenda point 7) Motion raised MWH Seconded AH £TBC Signage for Dog Fouling. • Parish Assets: Neen Sollars ~ £2,623.90 Milson ~ £1,020.00 1 Ordinary meeting of the Parish Council Milson and Neen Sollars 5. -

Sources for LEEBOTWOOD

Sources for LEEBOTWOOD This guide gives a brief introduction to the variety of sources available for the parish of at Leebotwood Shropshire Archives. Printed sources:. General works - These may also be available at Church Stretton library • Eyton, Antiquities of Shropshire • Transactions of the Shropshire Archaeological Society • Shropshire Magazine • Trade Directories which give a history of the town, main occupants and businesses, 1828-1941 • Victoria County History of Shropshire, vol.VIII • Parish Packs • Monumental Inscriptions Small selection of more specific texts (search www.shropshirearchives.org.uk for a more comprehensive list) • C61 Reading Room Leebotwood: a migrated medieval settlement – In Transactions of the Shropshire Archaeological Society, vol. LXV, 1987, pp38-40 • C64 Reading Room Antiquities of Shropshire, Vol. VI – R Eyton The Pound Inn in Leebotwood was built in 1650. The village shop, adjoining the Pound Inn, is first recorded in 1851 and until about 1917 it was occupied by the Preen family, PH/L/4/1/5 Sources on microfiche or film: Parish and non-conformist church registers Baptisms Marriages / Banns Burials St Mary’s church 1548-1998 1548-1997 / 1754-1997 1548-1997 1998-2006 originals only Methodist records - see Methodist Circuit Records (Reader’s Ticket needed) Up to 1900, registers are on www.findmypast.co.uk Census returns 1841, 1851(indexed), 1861, 1871, 1881, 1891, 1901 Census returns for the whole country to 1911 can be looked at on the Ancestry website Maps Ordnance Survey maps 25” to the mile and 6 “to the mile, c1880, c1901 (OS reference: old series XLIX.10 new series SJ SO4698 Newspapers Shrewsbury Chronicle, 1772 onwards (NB from 1950 as originals only – Reader’s Ticket required) Shropshire Star, 1964 onwards Archives: To see these sources you need a Shropshire Archives Reader's Ticket. -

Steeplewood Fold Magazine October

Dates for your Diary Sunday 4th Oct 10:30am Smethcott Ch. Holy Communion Wednesday 7th Oct 7:30pm Zoom Meeting Filling Station Thursday 8th Oct 12:15pm Horseshoes Seniors Lunch Club Thursday 8th Oct 7:30pm Stapleton Ch. Stapleton APCM Sunday 11th Oct 10:30am Stapleton Ch. Holy Communion St Michael and All Angels St Michael and All Angels Sunday 11th Oct 10:30am Longnor Ch. Morning Prayer Sunday 11th Oct 11:30am Longnor Ch. Longnor APCM Woolstaston Smethcott Tuesday 13th Oct 7:30pm Leebotwood VH Leebotwood APCM Wednesday 14th Oct 7:30pm Zoom meeting Smethcott WI Sunday 18th Oct 10:30am Longnor Ch. Holy Communion Sunday 18th Oct 10:30am Smethcott Ch. Morning Worship Steeplewood Fold Magazine Wednesday 21st Oct 7:30pm Woolstaston Ch. Woolstaston APCM Sunday 25th Oct 10:30am Longnor Ch. Morning Prayer Sunday 25th Oct 10:30am Dorrington VH Harvest Communion Monday 26th Oct 7:00pm Picklescott VH Smethcott APCM Wednesday 28th Oct 7:30pm Dorrington Ch./VH Dorrington APCM For further information on the above events see entry in Magazine St Mary St Mary Please forward any parish entries to your representative and all adverts directly to Longnor Leebotwood the team on [email protected]. All entries must be submitted no later than 14th October To organise subscription to this magazine please contact Emily Hill (07471 474924) or email [email protected] and monthly delivery can be arranged. St John the Baptist St Edward Stapleton Dorrington October 40p 40 1 We are the Benefice of To arrange a Christening (Baptism) or Useful Contacts Steeplewood Fold including: Wedding, please contact our Rector Rector Rev. -

All Stretton Census

No. Address Name Relation to Status Age Occupation Where born head of family 01 Castle Hill Hall Benjamin Head M 33 Agricultural labourer Shropshire, Wall Hall Mary Wife M 31 Montgomeryshire, Hyssington Hall Mary Ann Daughter 2 Shropshire, All Stretton Hall, Benjamin Son 4 m Shropshire, All Stretton Hall Sarah Sister UM 19 General servant Shropshire, Cardington 02 The Paddock Grainger, John Head M 36 Wheelwright Shropshire, Wall Grainger, Sarah Wife M 30 Shropshire, Wall Grainger, Rosanna Daughter 8 Shropshire, Wall Grainger, Mary Daughter 11m Church Stretton 03 Mount Pleasant Icke, John Head M 40 Agricultural labourer Shropshire, All Stretton Icke Elisabeth Wife M 50 Shropshire, Bridgnorth Lewis, William Brother UM 54 Agricultural labourer Shropshire, Bridgnorth 04 Inwood Edwards, Edward Head M 72 Sawyer Shropshire, Church Stretton Edwards, Sarah Wife M 59 Pontesbury Edwards Thomas Son UM 20 Sawyer Shropshire, Church Stretton Edwards, Mary Daughter UM 16 Shropshire, Church Stretton 05 Inwood Easthope, John Head M 30 Agricultural labourer Shropshire, Longner Easthope, Mary Wife M 27 Shropshire, Diddlebury Hughes, Jane Niece 3 Shropshire, Diddlebury 06 Bagbatch Lane ottage Morris James Head M 55 Ag labourer and farmer, 7 acres Somerset Morris Ellen Wife M 35 Shropshire, Clungunford Morris, Ellen Daughter 1 Shropshire, Church Stretton 07 Dudgley Langslow, Edward P Head M 49 Farmer 110 acres, 1 man Shropshire, Clungunford Langslow Emma Wife M 47 Shropshire, Albrighton Langslow, Edward T Son 15 Shropshire, Clungunford Langslow, George F Son -

Ludlow Bus Guide Contents

Buses Shropshire Ludlow Area Bus Guide Including: Ludlow, Bitterley, Brimfield and Woofferton. As of 23rd February 2015 RECENT CHANGES: 722 - Timetable revised to serve Tollgate Road Buses Shropshire Page !1 Ludlow Bus Guide Contents 2L/2S Ludlow - Clee Hill - Cleobury Mortimer - Bewdley - Kidderminster Rotala Diamond Page 3 141 Ludlow - Middleton - Wheathill - Ditton Priors - Bridgnorth R&B Travel Page 4 143 Ludlow - Bitterley - Wheathill - Stottesdon R&B Travel Page 4 155 Ludlow - Diddlebury - Culmington - Cardington Caradoc Coaches Page 5 435 Ludlow - Wistanstow - The Strettons - Dorrington - Shrewsbury Minsterley Motors Pages 6/7 488 Woofferton - Brimfield - Middleton - Leominster Yeomans Lugg Valley Travel Page 8 490 Ludlow - Orleton - Leominster Yeomans Lugg Valley Travel Page 8 701 Ludlow - Sandpits Area Minsterley Motors Page 9 711 Ludlow - Ticklerton - Soudley Boultons Of Shropshire Page 10 715 Ludlow - Great Sutton - Bouldon Caradoc Coaches Page 10 716 Ludlow - Bouldon - Great Sutton Caradoc Coaches Page 10 722 Ludlow - Rocksgreen - Park & Ride - Steventon - Ludlow Minsterley Motors Page 11 723/724 Ludlow - Caynham - Farden - Clee Hill - Coreley R&B Travel/Craven Arms Coaches Page 12 731 Ludlow - Ashford Carbonell - Brimfield - Tenbury Yarranton Brothers Page 13 738/740 Ludlow - Leintwardine - Bucknell - Knighton Arriva Shrewsbury Buses Page 14 745 Ludlow - Craven Arms - Bishops Castle - Pontesbury Minsterley Motors/M&J Travel Page 15 791 Middleton - Snitton - Farden - Bitterley R&B Travel Page 16 X11 Llandridnod - Builth Wells - Knighton - Ludlow Roy Browns Page 17 Ludlow Network Map Page 18 Buses Shropshire Page !2 Ludlow Bus Guide 2L/2S Ludlow - Kidderminster via Cleobury and Bewdley Timetable commences 15th December 2014 :: Rotala Diamond Bus :: Monday to Saturday (excluding bank holidays) Service No: 2S 2L 2L 2L 2L 2L 2L 2L 2L 2L Notes: Sch SHS Ludlow, Compasses Inn . -

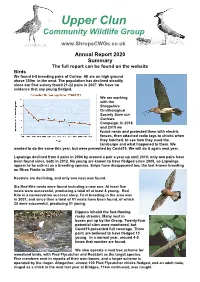

2020 UCCWG Short Report

Upper Clun Community Wildlife Group www.ShropsCWGs.co.uk Annual Report 2020 Summary The full report can be found on the website Birds We found 6-8 breeding pairs of Curlew. All are on high ground above 350m. in the west. The population has declined steadily since our first survey found 21-22 pairs in 2007. We have no evidence that any young fledged. We are working with the Shropshire Ornithological Society Save our Curlews Campaign. In 2018 and 2019 we found nests and protected them with electric fences, then attached radio tags to chicks when they hatched, to see how they used the landscape and what happened to them. We wanted to do the same this year, but were prevented by Covid19. We will do it again next year. Lapwings declined from 6 pairs in 2004 by around a pair a year up until 2010; only two pairs have been found since, both in 2012. No young are known to have fledged since 2008, so Lapwings appear to be extinct as a breeding species. Snipe have disappeared too, the last known breeding on Rhos Fiddle in 2009. Kestrels are declining, and only one nest was found. Six Red Kite nests were found including a new one. At least five nests were successful, producing a total of at least 8 young. Red Kite is a conservation success story. First breeding in the area was in 2007, and since then a total of 51 nests have been found, of which 35 were successful, producing 51 young. Dippers inhabit the fast-flowing rocky streams.