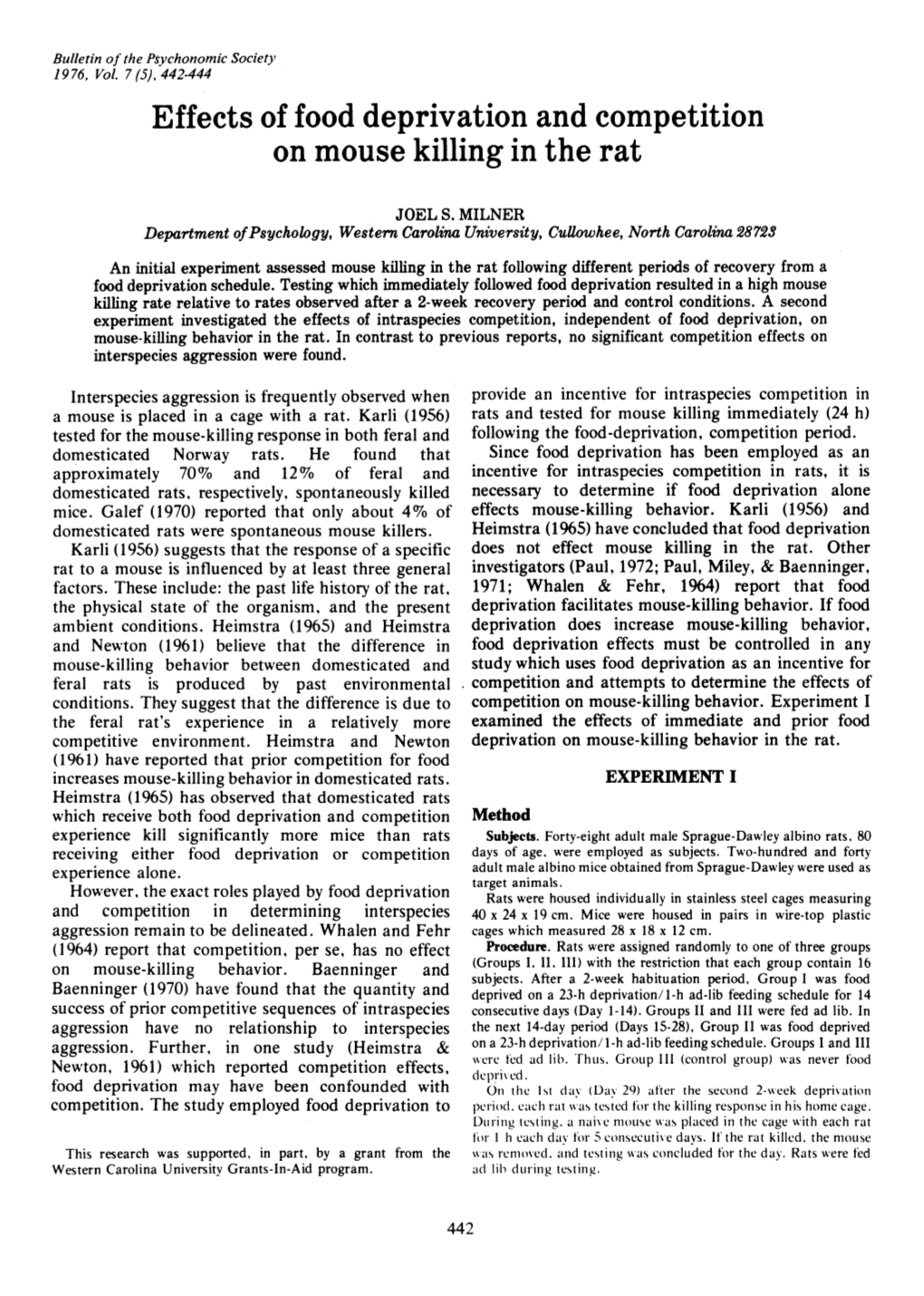

Effects of Food Deprivation and Competition on Mouse Killing in the Rat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Cage's Entanglement with the Ideas Of

JOHN CAGE’S ENTANGLEMENT WITH THE IDEAS OF COOMARASWAMY Edward James Crooks PhD University of York Music July 2011 John Cage’s Entanglement with the Ideas of Coomaraswamy by Edward Crooks Abstract The American composer John Cage was famous for the expansiveness of his thought. In particular, his borrowings from ‘Oriental philosophy’ have directed the critical and popular reception of his works. But what is the reality of such claims? In the twenty years since his death, Cage scholars have started to discover the significant gap between Cage’s presentation of theories he claimed he borrowed from India, China, and Japan, and the presentation of the same theories in the sources he referenced. The present study delves into the circumstances and contexts of Cage’s Asian influences, specifically as related to Cage’s borrowings from the British-Ceylonese art historian and metaphysician Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. In addition, Cage’s friendship with the Jungian mythologist Joseph Campbell is detailed, as are Cage’s borrowings from the theories of Jung. Particular attention is paid to the conservative ideology integral to the theories of all three thinkers. After a new analysis of the life and work of Coomaraswamy, the investigation focuses on the metaphysics of Coomaraswamy’s philosophy of art. The phrase ‘art is the imitation of nature in her manner of operation’ opens the doors to a wide- ranging exploration of the mimesis of intelligible and sensible forms. Comparing Coomaraswamy’s ‘Traditional’ idealism to Cage’s radical epistemological realism demonstrates the extent of the lack of congruity between the two thinkers. In a second chapter on Coomaraswamy, the extent of the differences between Cage and Coomaraswamy are revealed through investigating their differing approaches to rasa , the Renaissance, tradition, ‘art and life’, and museums. -

A Further Investigation of the Development of Mouse-Killing in Rats

A further investigation of the development of mouse-killing in rats Norman W. Heimstra UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH DAKOTA Abstract in a 24 x 12 x 12 in wooden box with a hardware cloth Several previous investigations have suggested that top and bottom. The same animals were paired on competitive experience is an important factor in the each successive day. A metal food container, 2 in high development of the mouse-killing response in rats. and 1 in in diameter, was secured to the center of the However, the question of whether the competition in floor of the test box. Only one rat of a pair could eat volved or food deprivation aSSOCiated with the competi from this container which held mOistened, ground tion is the critical factor has been raised. In the present laboratory pellets. A pair of rats was left in this study three groups of rats were used. In one group situation for 5 min. and then returned to their individual (N = 40) rats were food deprived and were placed daily, home cages. Animals were then allowed free access in pairs, in a situation where they could compete for to food pellets for slightly less than 2 hr. At that time food . A second group (N = 20) was food deprived but not the excess pellets were removed from the cage and an exposed to the competitive situation, while a third adult white mouse was placed in the cage. The mouse was group (N = 20) was not food deprived. Animals were left in the cage for 30 min. at which time it was removed tested daily for 15 consecutive days for the development if it had not been killed. -

Ofenge~6) a U

RICE UNIVERSITY "Kin with Kin and Kind with Kind Confound": Pity, Justice, and Family Killing in Early Modern Dramas Depicting Islam by Joy Pasini A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE Doctor of Philosophy ~--- Meredith Skura, Libbie Shearn Moody Professor ofEnge~6) a u avid Cook, Associate Professor, Religious Studies Houston, Texas DECEMBER 2011 Abstract "Kin with Kin and Kind with Kind Confound": Pity, Justice, and Family Killing in Early Modem Dramas Depicting Islam By Joy Pasini This dissertation examines the early modem representation of the Ottoman sultan as merciless murderer of his own family in dramas depicting Islam that are also revenge tragedies or history plays set in empires. This representation arose in part from historical events: the civil wars that erupted periodically from the reign of Sultan Murad I (1362-1389) to that of Sultan Mehmed III (1595-1603) in which the sultan killed family members who were rivals to the throne. Drawing on these events, theological and historical texts by John Foxe, Samuel Purchas, and Richard Knolles offered a distorted image of the Ottoman sultan as devoid of pity for anyone, but most importantly family, an image which seeped into early modem drama. Early modem English playwrights repeatedly staged scenes in the dramas that depict Islam in which one member of a family implores another for pity and to remain alive. However, family killing became diffuse and was not the sole province of the Ottoman sultan or other Muslim character: the Spanish, Romans, and the Scythians also kill their kin. Additionally, they kill members of their own religious, ethnic, and national groups as family killing expands to encompass a more general self destruction, self sacrifice, and self consumption. -

THE COLLECTED POEMS of HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam

1 THE COLLECTED POEMS OF HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam 2 PREFACE With the exception of a relatively small number of pieces, Ibsen’s copious output as a poet has been little regarded, even in Norway. The English-reading public has been denied access to the whole corpus. That is regrettable, because in it can be traced interesting developments, in style, material and ideas related to the later prose works, and there are several poems, witty, moving, thought provoking, that are attractive in their own right. The earliest poems, written in Grimstad, where Ibsen worked as an assistant to the local apothecary, are what one would expect of a novice. Resignation, Doubt and Hope, Moonlight Voyage on the Sea are, as their titles suggest, exercises in the conventional, introverted melancholy of the unrecognised young poet. Moonlight Mood, To the Star express a yearning for the typically ethereal, unattainable beloved. In The Giant Oak and To Hungary Ibsen exhorts Norway and Hungary to resist the actual and immediate threat of Prussian aggression, but does so in the entirely conventional imagery of the heroic Viking past. From early on, however, signs begin to appear of a more personal and immediate engagement with real life. There is, for instance, a telling juxtaposition of two poems, each of them inspired by a female visitation. It is Over is undeviatingly an exercise in romantic glamour: the poet, wandering by moonlight mid the ruins of a great palace, is visited by the wraith of the noble lady once its occupant; whereupon the ruins are restored to their old splendour. -

Justice and Vengeance in Golden Age Detective Fiction

People‘s Democratic Republic of Algeria Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research Mohamed Kheider University of Biskra Faculty of Letters and Foreign Languages Department of Foreign Languages English Division Justice and Vengeance in Golden Age Detective Fiction the case of Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master Degree in Literature and Civilization Submitted by: Supervised by: Fekih Ines Mrs. Haddad Meymouna BOARD OF EXAMINERS Chairperson: Dr. Boulgroun Adel Mohamed Kheider University of Biskra Supervisor: Mrs. Haddad Meymouna Mohamed Kheider University of Biskra Examiner: Ms. Hamed Halima Mohamed Kheider University of Biskra Examiner: Mr. Yasser Sadrati Mohamed Kheider University of Biskra 2019/2020 Dedications To my beloved family and friends… Yours, Fekih Ines I Acknowledgments First of all, all praise is due to Allah who gave me the courage and the will to accomplish this work. I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor Mrs. Haddad Meymouna for her guidance and support during the elaboration of this research. I would acknowledge, with great respect, the jury members: Mr. Boulegroune Adel, Mr. Sedrati Yasser and Mrs. Hamed Halima for their constructive feedback and suggestions. I am profoundly thankful to my teachers in the English Department at the University of Biskra. II Abstract Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express is undoubtedly one of her greatest mystery novels. This novel has successfully blurred the line between justice and revenge. Therefore, this research investigates the motive behind the twelve passengers’ murder of Cassetti. It aims at exploring the themes of justice and vengeance as instigated by Christie in the novel as well as examining how the author manipulated the reader into sympathizing with the murderers. -

Eldon Black Album Collection

Albums Eldon Black Album Collection These albums are only available for use by ASU students, faculty, and staff. Ask at the Circulation Desk for assistance. (Use the Adobe "Find" to locate song(s) and/or composer(s).) Catalog Number Title Notes 1 Falstaff-Verdi Complete 2 La Perichole Complete 3 Tosca-Puccini Complete 4 Cavalleria Rusticana-Mascagni Complete 5 The Royal Family of Opera 5A lo son l'umile ancella from Adriana Lecouvreur by Cilea 5B Come rugiada al cespite from Ernani by Verdi 5C In questo suolo a lusingar tua cura from La Favorita by Donizetti 5D E lucevan le stelle from Tosca by Puccini 5E Garden Scene Trio from Don Carlo by Verdi 5F Oh, di qual onta aggravasi from Nabucco by Verdi 5G In quelle trine morbide from Manon Lescaut by Puccini 5H Dulcamara/Nemorino duet from "Ecco il magico liquor" from L'Elisir D'Amore by Donizetti 5I Il balen from Il Trovatore by Verdi 5J Mon coeur s'ouvre a ta voix from Samson et Dalila by Saint-Saens 5K Bel raggio lusingheir from Semiramide by Rossini 5L Le Veau d'or from Faust by Gounod 5M Page's Aria from Les Huguenots by Meyerbeer 5N Depuis le jour from Louise by Charpentier 5O Prize Song from Die Meistersinger by Wagner 5P Sois immobile from William Tell by Rossini 5Q Cruda sorte from L'Italiana in Algeri by Rossini 5R Der Volgelfanger bin ich from The Magic Flute by Mozart 5S Suicidio! from La Gioconda by Ponchielli 5T Alla vita che t'arride from A Masked Ball by Verdi 5U O mio babbino caro from Gianni Schicchi by Puccini 5V Amor ti vieta from Fedora by Giordano 5W Dei tuoi figli from -

Experimental Practices of Music and Philosophy in John Cage and Gilles Deleuze

Experimental Practices of Music and Philosophy in John Cage and Gilles Deleuze Iain CAMPBELL This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Kingston University for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Centre for Research in Modern European Philosophy. October 2015 Abstract In this thesis we construct a critical encounter between the composer John Cage and the philosopher Gilles Deleuze. This encounter circulates through a constellation of problems found across and between mid-twentieth century musical, artistic, and philosophical practices, the central focus for our line of enquiry being the concept of experimentation. We emphasize the production of a method of experimentation through a practice historically situated with regards to the traditions of the respective fields of music and philosophy. However, we argue that these experimental practices are not reducible to their historical traditions, but rather, by adopting what we term a problematic reading, or transcendental critique, with regards to historical givens, they take their historical situation as the site of an experimental departure. We follow Cage through his relation to the history of Western classical music, his contemporaries in the musical avant-garde, and artistic movements surrounding and in some respects stemming from Cage’s work, and Deleuze through his relation to Kant, phenomenology, and structuralism, in order to map the production of a practice of experimentation spanning music, art, and philosophy. Some specific figures we engage with in these respective traditions include Jean-Phillipe Rameau, Pierre Schaeffer, Marcel Duchamp, Pierre Boulez, Robert Morris, Yoko Ono, La Monte Young, Edmund Husserl, Maurice- Merleau-Ponty, Alain Badiou, and Félix Guattari. -

Literary Study, Measurement, and the Sublime: Disciplinary Assessment

LITERARY STUDY, MEASUREMENT, AND THE SUBLIME: DISCIPLINARY ASSESSMENT Editors Donna Heiland and Laura J. Rosenthal With the assistance of Cheryl Ching LITERARY STUDY, MEASUREMENT, AND THE SUBLIME: DISCIPLINARY ASSESSMENT DONNA HEILAND AND LAURA J. ROSENTHAL, EDITORS WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF CHERYL CHING The Teagle Foundation is a New York-based philanthropic organization that intends to be an influential national voice and a catalyst for change to improve undergraduate student learning in the arts and sciences. The opinions, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in the essays included in this collection are the authors’ own and should not be attributed to the Foundation. Copyright © 2011 by The Teagle Foundation. “18-Item Need for Cognition Scale” by John T. Cacioppo, Richard E. Petty, and Chuan Feng Kao was first published in Journal of Personality Assessment 48.3 (1984) and is reprinted with permission of the authors. “A Progressive Case for Educational Standardization: How Not to Respond to Calls for Common Standards,” by Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein was first published in the May-June 2008 issue of Academe. Copyright © 2008 by American Association of University Professors. The essay has been revised by the authors and is reprinted with permission of the original publisher. “Elephant Painting” by Hong, date unknown, is reprinted with permission from ExoticWorldGifts.com. Published by The Teagle Foundation 570 Lexington Avenue, 38th Floor, New York, New York 10022 www.teagle.org All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted, reproduced or transmitted in any format or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording and information storage and retrieval, without written permission from the publisher. -

Maxton Police Chief Takes Tarboro Job Cites Board Interference for Departure

Vote May 8th for Keep the mega dump Bob Davis out of for Scotland County Commissioner scotland county Paid For By Bill Owens | Not Authorized By Candidate 299TH EDITION OUR 128TH YEAR WE PRINT ON 100% RECYCLED NewSPRINT Saturday Today’s weather Sports What’s inside: Contact us Classified Ads . .5B Main number: 276-2311 88 HIGH Comics. .4B Subscription/Delivery Scotland wins Community Calendar. 3A concerns . Ext. 18 5 Obituaries. .2A Classifieds. .Ext. 10 conference Service Directory . .6B Announcements. Ext. 15 May Sports . 1B Missing your paper? see page 1B Your TV . .3B Call Ext. 18 by 10 a.m. 2012 64 LOW The Voice of Scotland County | Established 1882 | www.LaurinburgExchange.com | $1.00 Maxton police chief takes Tarboro job Cites board interference for departure Johnny Woodard Monday, and expects to leave 30 two positions with the department Staff Reporter days later. because of budget woes. Williams Williams, who has served as said the department had 14 posi- Maxton Police Damon Williams Maxton’s top cop for about two tions when he accepted the job in confirmed on Friday that he was years, was critical of the town April 2010, and after the recent leaving to head the police force in board’s “micromanagement.” round of cuts would be down Tarboro, saying that part of the rea- “The fractured nature of local to nine positions, including the son for his departure was the town politics and the micromanagement chief’s. board’s handling of police layoffs. of the entire layoff process are “I am a forward-thinking person, The 33-years-old Williams said some of the reasons I am leaving,” looking to progress and advance he plans to begin his new job Williams said. -

Study Materials for Movie

A Film Produced by the 222 New York Street Rapid City, SD 57701 • https://www.journeymuseum.org Through a Grant from the With Funds from the National Endowment for the Humanities Filmed on Location in the Journey Museum © The Journey Museum and Dakota Daughters (Geraldine Goes in Center, Joyce Jefferson, and Lillian Witt.) All Rights Reserved. Study materials compiled by Anna Marie Thatcher. “America is an old house. We can never declare the work over. Wind, flood, wrought, and human upheavals batter a structure that is already fighting whatever flaws were left unattended in the original foundation. When you live in an old house, you may not want to go into the basement after a storm to see what the rains have wrought. Choose not to look, however, at your own peril. The owner of an old house knows that whatever you are ignoring will never go away. Whatever is lurking will fester whether you choose to look or not. Ignorance is no protection from the consequences of inaction. Whatever you are wishing away will gnaw at you until you gather the courage to face what you would rather not see.” Isabel Wilkerson CASTE: The Origins of Our Discontents 2 REFLECTIONS ON THE MASSACRE AT WOUNDED KNEE Three Women, Three Stories, Three Cultures Written and Presented by Dakota Daughters with Geraldine Goes in Center as Kimimila (Sitting Bull’s Daughter) Lillian Witt as Sadie Babcock (a Rancher’s Wife) Joyce Jefferson as Mattie Elmira Richardson (Engaged to a Buffalo Soldier) Each performer researched and wrote her part of this historical interpretation of the events leading up to the massacre at Wounded Knee Creek in 1890. -

Portrait of an Animal Rights Activist

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 1996 The Caring Sleuth: Portrait of an Animal Rights Activist Kenneth J. Shapiro Animals and Society Institute Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/acwp_awap Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Civic and Community Engagement Commons, and the Politics and Social Change Commons Recommended Citation Shapiro, Kenneth J., "The Caring Sleuth: Portrait of an Animal Rights Activist" (1996). Animal Welfare Collection. 30. https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/acwp_awap/30 This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Caring Sleuth: Portrait of an Animal Rights Activist Kenneth Shapiro PSYCHOLOGISTS FOR THE ETHICAL TREATMENT OF ANIMALS The present study of the psychology of animal rights activists utilizes a qualitative analytic method based on two forms of data: a set of questionnaire protocols completed by grassroots activists and of autobiographical accounts by movement leaders. The resultant account keys on the following descriptives: (1) an attitude of caring, (2) suffering as an habitual object of perception, and (3) the aggressive and skillful uncovering and investigation of instances of suffering. In a final section, the investigator discusses tensions and conflicts arising from these three themes and various ways of attempting to resolve them. Manny Bernstein recalls the German shepherd who licked his toddler face when he fell off his tricycle, and the sadness he felt looking at a gorilla confined in a barren cage at the local zoo. -

Writings Through John Cage's Music, Poetry, And

Writings through John Cage’s Music, Poetry, and Art Writings through John Cage’s Music, Poetry, and Art Edited by David W. Bernstein and Christopher Hatch THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO AND LONDON DAVID W. BERNSTEIN is associate professor of music and head of the Music Department at Mills College. CHRISTOPHER HATCH has retired from the Department of Music at Columbia University. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2001 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 2001 Printed in the United States of America 10090807060504030201 54321 ISBN (cloth): 0-226-04407-6 ISBN (paper): 0-226-04408-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Writings through John Cage’s music, poetry, and art / edited by David W. Bernstein and Christopher Hatch. p. cm. Proceedings from the conference entitled “Here Comes Everybody: The Music, Poetry, and Art of John Cage” which took place at Mills College in Oakland, Calif. from Novem- ber 15 to 19, 1995. Includes index. ISBN 0-226-04407-6 — ISBN 0-226-04408-4 (pbk.) 1. Cage, John—Criticism and interpretation—Congresses. I. Bernstein, David W., 1951–. II. Hatch, Christopher. ML410.C24 W74 2001 780Ј.92—dc21 00-011440 ᭺ϱ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American Na- tional Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992. To Gordon Mumma CONTENTS Acknowledgments ix Introduction David W. Bernstein 1 One “In Order to Thicken the Plot”: Toward a Critical Reception of Cage’s Music David W.