Learning Survival Skills by Heather Mansfield, UCLA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Full Article

ARTICLE ADAPTING COPYRIGHT FOR THE MASHUP GENERATION PETER S. MENELL† Growing out of the rap and hip hop genres as well as advances in digital editing tools, music mashups have emerged as a defining genre for post-Napster generations. Yet the uncertain contours of copyright liability as well as prohibitive transaction costs have pushed this genre underground, stunting its development, limiting remix artists’ commercial channels, depriving sampled artists of fair compensation, and further alienating netizens and new artists from the copyright system. In the real world of transaction costs, subjective legal standards, and market power, no solution to the mashup problem will achieve perfection across all dimensions. The appropriate inquiry is whether an allocation mechanism achieves the best overall resolution of the trade-offs among authors’ rights, cumulative creativity, freedom of expression, and overall functioning of the copyright system. By adapting the long-standing cover license for the mashup genre, Congress can support a charismatic new genre while affording fairer compensation to owners of sampled works, engaging the next generations, and channeling disaffected music fans into authorized markets. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 443 I. MUSIC MASHUPS ..................................................................... 446 A. A Personal Journey ..................................................................... 447 B. The Mashup Genre .................................................................... -

The AGA Song Book up to Date

3rd Edition Songs, Poems, Stories and More! Edited by Bob Felice Published by The American Go Association P.O. Box 397, Old Chelsea Station New York, N.Y., 10113-0397 Copyright 1998, 2002, 2006 in the U.S.A. by the American Go Association, except where noted. Cover illustration by Jim Rodgers. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without prior written permission of the copyright holder, except for brief quotations used as part of a critical review. Introductions Introduction to the 1st Edition When I attended my first Go Congress three years ago I was astounded by the sheer number of silly Go songs everyone knew. At the next Congress, I wondered if all these musical treasures had ever been printed. Some research revealed that the late Bob High had put together three collections of Go songs, but the last of these appeared in 1990. Very few people had these song books, and some, like me, weren’t even aware that they existed. While new songs had been printed in the American Go Journal, there was clearly a need for a new collection of Go songs. Last year I decided to do whatever I could to bring the AGA Song Book up to date. I wanted to collect as many of the old songs as I could find, as well as the new songs that had been written since Bob High’s last song book. You are holding in your hands the book I was looking for two years ago. -

Regulatory Incentives for Innovation

REGULATORY INCENTIVES FOR INNOVATION: THE FDA’S BREAKTHROUGH THERAPY DESIGNATION Amitabh Chandra1 Jennifer Kao2 Kathleen L. Miller3 Ariel D. Stern4 Abstract In approving new medical products, regulators confront a tradeoff between speeding a new product to market and collecting additional information about its quality. Alternatively, with the right allocation of resources, this tradeoff function may be “shifted outward,” thereby allowing important products to come to market more quickly without compromising quality evaluation. We study the FDA’s Breakthrough Therapy Designation (BTD), a novel policy tool that was created to accelerate the clinical development and regulatory approval processes for developers of high-value therapies by increasing feedback and communication with regulators during later phases of drug development. Using algorithmic matching models, we assess the impact of the BTD program on measures of (1) time-to-market and (2) post-approval drug safety. We find that the BTD program shortened late-stage clinical development times by 24 percent. We do not find evidence of a difference in the ex post safety profile of drugs with (vs. without) the BTD. In exploring mechanisms, we find support for reduced BTD trial design com- plexity, but not for trial size as driving these findings. The results suggest that targeted policy tools can shorten R&D periods without compromising the quality of new products. * The authors are grateful to seminar participants at the Allied Social Science Associations meeting, the Amer- ican Society of Health Economists Annual Conference, the Bates-White Life Sciences Symposium, the Harvard- MIT Center for Regulatory Science, the Munich Summer Institute, NABE Tech Conference, the NBER Produc- tivity Seminar, the Spreestadt-Forum on Health Care, and the University of San Francisco for valuable comments. -

The Breakthrough Podcast

Alison Dean (00:09): Theorem is the leading innovation and engineering firm for the fortune 1,000. We design, build, and deliver enterprise-scale technology solutions and are very excited to present The Breakthrough Podcast. An ongoing series where we interview technology leaders to share their experiences and perspectives on what's next in tech. Alison Dean (00:38): Welcome to The Breakthrough. I'm Alison Dean VP of Operations at Theorem. Today we are talking with Scott Olechowski, currently the Co-Founder & Chief Product Officer at Plex, which according to tomsguide.com happens to be the best media server app that you can get. Scott sent me this quote from Mark Twain, "Continuous improvement is better than delayed perfection." So hello, Scott. Scott Olechowski (01:03): Hey, Alison. How are you? Alison Dean (01:05): I'm good. What does that quote mean to you? Scott Olechowski (01:07): To me, it's the heart of what we do in software in particular, but just in product, generally, you have to ship. You have to get what you're doing out there and it's never finished. You're always improving it. You're always working on it. You always know you can do better. You always know you're going to get feedback. To me, it's just that ethos of you're never done and you're just getting started every time you ship. Alison Dean (01:30): I can only imagine as someone that leads product for a company that when you're looking at anything now in your life, you're literally thinking, "Well, I would improve this here. -

Mary J Blige No More Drama Album Download Zip

1 / 5 Mary J Blige No More Drama Album Download Zip Dec 26, 2018 — Mary J. Blige Growing Pains album download ZIP 208 2007 - R&B, ... No More Drama is the fifth studio album by American R&B recording artist .... Si no Los archivos disponibles en este blog están sujetos a la ley de ... Mary J Blige Discography 320 10 Albums R B by dragan09 rar. ... Joel's first greatest hits compilation, which compiles the majority of his most ... For Tomorrow We Die 4:16 2. d384263321 Download Kendrick Lamar discography free rar zip album cds .... In addition, you can search the most popular songs, new releases, and songs from ... like to download the music more often and with something that is user friendly. ... a significant album from the past, and any record not in our archives is eligible. ... help folks like Heavy D. and Mary J. Blige get off the ground and discovered .... Скачать Mary J. Blige - No More Drama mp3 release album free and without registration. On this page you can listen to mp3 music free or download album or mp3 track to your PC, phone or tablet. ... Find music audio mp3 or zip. mp3 or zip.. Shop for Vinyl, CDs and more from Mary J. Blige at the Discogs Marketplace. ... In November 2010, Billboard Magazine ranked Blige as the most successful female ... Remix album art ... 112 616-2, Mary J. Blige - No More Drama album art .... Aug 26, 2018 — Following the commercial success of 2001's No More Drama, Blige's Love & Life came at a time in her professional and personal life where she ... -

Disclosure 2

Corporate Responsibility Communication CSR Communication Report 26-1, Nishi-Shinjuku 1-chome, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo, 160-8338, Japan URL: http://www.sompo-hd.com/en/ This report is printed on FSC-certified paper using vegetable oil-based ink for environmentally friendly printing. CONTENTS 01 Editorial Policy/Company Outline ……………………………………………………………………………… 02 Sompo Japan Nipponkoa Group at a Glance …………………………………………………………………… 03 Top Commitment ………………………………………………………………………………………………… 04 CSR Milestones of the Sompo Japan Nipponkoa Group ……………………………………………………… 07 Management Strategies and CSR ………………………………………………………………………………… 09 CSR and Environmental Management Framework …………………………………………………………… 10 Sompo Japan Nipponkoa Group’s CSR Promotion……………………………………………………………… 11 Stakeholder Engagement ………………………………………………………………………………………… 15 Sompo Japan Nipponkoa Group’s CSR Training ………………………………………………………………… 17 Special Article The United Nations Decade of ESD Highlights of the Sompo Japan Nipponkoa Group’s Achievements ………………………………………… 19 Declarations to Society and Participation in CSR Initiatives …………………………………………………… 21 External Recognition ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 23 Message from an External Expert ……………………………………………………………………………… 24 Mr. John Elkington, Co-Founder and Executive Chairman of Volans Providing Products and Services that Contribute to Security, Health, and Wellbeing ……………………… 25 Material Issue 1 Increasing Customer Satisfaction by Providing Products and Services that Meet Consumer Needs Tackling Global Environmental Issues …………………………………………………………………………… -

The Best Songs, Records, and Bands Transport You Back to the First Moment You Heard Them Each and Every Time They Play

The best songs, records, and bands transport you back to the first moment you heard them each and every time they play. Whether you caught a house party gig after Better Than Ezra formed in 1988 at Louisiana State University, heard “Good” on the radio once it hit #1 during 1995, became a fan following Taylor Swift’s famous cover of “Breathless” in 2010, or saw them headlining sheds in 2018, you most likely never forgot that initial introduction to the New Orleans quartet founded by Kevin Griffin [lead vocals, guitar, piano] and Tom Drummond [bass, backing vocals]. Those hummable melodies, unshakable guitar riffs, and confessional lyrics quietly cemented the group as an enduring force in rock music. How many acts can boast being the inspiration of a classic Saturday Night Live skit? Very few. Speaking of incredible accomplishments, they occupy rarified air with spots on Billboard’s “100 Greatest Alternative Songs of All Time” and “100 Greatest Alternative Artists of All Time” as of 2018. Additionally, 2018 also marked 25 years since the arrival of the breakthrough album Deluxe. Maintaining a steady pace forward, the new single “GRATEFUL” garnered acclaim from Billboard who praised its “highly commercial, anthemic sheen that certainly pairs nicely with the approach of Deluxe.” The story of Better Than Ezra began before the nineties explosion they remain so often associated with ever even happened. Griffin and Drummond comprised the core of the band at its onset as they hit the road and won over one fan at a time beginning in 1989. This fan base would go on to be known as “Ezralites” by the time the first pressing of Deluxe landed independently in 1993. -

A$Ap Ferg to Release Always Strive and Prosper on April 22

ND A$AP FERG TO RELEASE ALWAYS STRIVE AND PROSPER ON APRIL 22 SOPHOMORE ALBUM AVAILABLE FOR PRE-ORDER MARCH 25TH AT ALL DIGITAL MUSIC PROVIDERS [New York, NY – March 22, 2016] Fresh off of taking Austin, TX by storm with his crowd-pleasing show opening performance of his hit single “New Level” at the MTV Woodies/10 for 16 Music Festival, A$AP Ferg announces today that his highly anticipated sophomore album Always Strive and Prosper is confirmed for an April 22nd release on A$AP Worldwide/Polo Grounds Music/RCA Records. Always Strive and Prosper will be available for pre-order on March 25th at all digital music providers. Fans who pre-purchase the album will receive an instant download of Ferg’s current single “New Level” featuring Future and the brand new track “Let It Bang” featuring ScHoolboyQ. Always Strive and Prosper is destined to be the breakthrough album that clearly defines the Trap Lord’s footing in the rap game. Introspective and entertaining, Ferg delves deep into topics ranging from his Harlem neighborhood, “Hungry Ham” (Hamilton Heights), to working at Ben & Jerry’s and everything in between. “This album is by far the best work I've created and showcases my versatility and taste in the music that I love,” states Ferg. “The mission for this album is for my fans to get a deeper look into my life; to know my origin, my family and the obstacles I've faced while growing up. More importantly, I want to encourage people to always strive and prosper because if an inner city kid from Harlem, NY can make it then they can as well.” A$AP Ferg emerged on the music scene in 2012 as one of the leading members of the Harlem, NY collective, A$AP Mob. -

A-570-053 Investigation Public Document E&C VI: MJH/TB MEMORANDUM FOR: Gary Taverman Deputy Assistant Secretary for Antid

A-570-053 Investigation Public Document E&C VI: MJH/TB MEMORANDUM FOR: Gary Taverman Deputy Assistant Secretary for Antidumping and Countervailing Duty Operations, performing the non-exclusive functions and duties of the Assistant Secretary for Enforcement and Compliance THROUGH: P. Lee Smith Deputy Assistant Secretary for Policy and Negotiations James Maeder Senior Director, performing the duties of the Deputy Assistant Secretary for AD/CVD Operations Robert Heilferty Acting Chief Counsel for Trade Enforcement and Compliance Albert Hsu Senior Economist, Office of Policy FROM: Leah Wils-Owens Office of Policy, Enforcement & Compliance DATE: October 26, 2017 SUBJECT: China’s Status as a Non-Market Economy Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................ 4 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ................................................................................... 8 SUMMARY OF COMMENTS FROM PARTIES......................................................................... 9 ANALYSIS ................................................................................................................................... 11 Factor One: The extent to which the currency of the foreign country is convertible into the currency of other countries. .......................................................................................................... 12 A. Framework of the Foreign Exchange Regime ................................................................ 12 -

49 Web Ballot 1.Indd

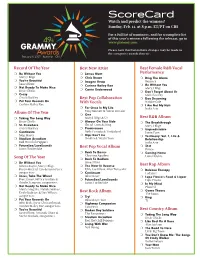

ScoreCard Watch and predict the winners! Sunday, Feb. 11, at 8 p.m. ET/PT on CBS For a full list of nominees, and for a complete list of this year’s winners following the telecast, go to www.grammy.com. Please note that last-minute changes may be made to the categories awarded on-air. Record Of The Year Best New Artist Best Female R&B Vocal ❍ Be Without You ❍ James Blunt Performance Mary J. Blige ❍ Chris Brown ❍ Ring The Alarm ❍ You’re Beautiful ❍ Imogen Heap Beyoncé James Blunt ❍ Corinne Bailey Rae ❍ Be Without You ❍ Not Ready To Make Nice ❍ Carrie Underwood Mary J. Blige Dixie Chicks ❍ Don’t Forget About Us ❍ Crazy Mariah Carey Gnarls Barkley Best Pop Collaboration ❍ Day Dreaming ❍ Put Your Records On With Vocals Natalie Cole Corinne Bailey Rae ❍ I Am Not My Hair ❍ For Once In My Life India.Arie Tony Bennett & Stevie Wonder Album Of The Year ❍ One ❍ Taking The Long Way Mary J. Blige & U2 Best R&B Album Dixie Chicks ❍ Always On Your Side ❍ The Breakthrough ❍ St. Elsewhere Sheryl Crow & Sting Mary J. Blige Gnarls Barkley ❍ Promiscuous ❍ Unpredictable ❍ Continuum Nelly Furtado & Timbaland Jamie Foxx John Mayer ❍ Hips Don’t Lie ❍ Testimony: Vol. 1, Life & ❍ Stadium Arcadium Shakira & Wyclef Jean Relationship Red Hot Chili Peppers India.Arie ❍ FutureSex/LoveSounds Best Pop Vocal Album ❍ 3121 Justin Timberlake Prince ❍ Back To Basics ❍ Coming Home Christina Aguilera Lionel Richie Song Of The Year ❍ Back To Bedlam ❍ Be Without You James Blunt Johnta Austin, Mary J. Blige, ❍ The River In Reverse Best Rap Album Bryan-Michael Cox & Jason Perry, Elvis Costello & Allen Toussaint ❍ Release Therapy songwriters ❍ Continuum Ludacris ❍ Jesus, Take The Wheel John Mayer ❍ Lupe Fiasco’s Food & Liquor Brett James, Hillary Lindsey & ❍ FutureSex/LoveSounds Lupe Fiasco Gordie Sampson, songwriters Justin Timberlake ❍ In My Mind ❍ Not Ready To Make Nice Pharrell Martie Maguire, Natalie Maines, Best Rock Album ❍ Game Theory Emily Robison & Dan Wilson, The Roots songwriters ❍ Try! ❍ King ❍ Put Your Records On John Mayer Trio T.I. -

WPP Pro Bono Work 2014 PDF 3.9MB

Pro bono work 2014 A selection of campaigns from WPP companies Contents Introduction – from our CEO 1 About the Group’s pro bono work 2 Showcase Environment 4 Health 18 Communities 35 Human rights 41 The arts 53 Environment page 4 Health page 18 Communities page 35 Education 58 Human rights page 41 The arts page 53 Education page 58 This report, together with our Sustainability Report, Annual Report, trading statements, news releases presentations, and previous Sustainability Reports, are available online at wpp.com Introduction – from our CEO One of our proudest traditions Charities and not-for-profit organisations need This isn’t just good for our pro bono clients but at WPP is the contribution the best quality communications services to engage for our business too. Pro bono campaigns are an with the public and policy makers, to raise funds, opportunity for our people to explore and develop our companies make through to recruit new members and to achieve their campaign their creativity and to create meaningful work that pro bono work – creative work objectives. However, with limited financial resources supports their own professional and personal they often can’t prioritise these services. development. The success of their efforts is recognised for charities at little or no fee. in the many awards won by these campaigns each Pro bono work, creative services provided for little year, which is good for our companies too. or no fee, can make a real difference. It gives organisations working in areas such as education, I’m pleased to recognise and thank our people for human rights, health, arts and the environment access their work in this area during 2014, and to share to the best creative talent and insight, enabling them with you some of the inspiring pro bono work to reach out and make a difference in the world. -

Breakthroughs, Deadlines, and Self-Reported Progress: Contracting for Multistage Projects∗

Breakthroughs, Deadlines, and Self-Reported Progress: Contracting for Multistage Projects∗ Brett Green Curtis R. Taylor UC Berkeley (Haas) Duke University [email protected] [email protected] faculty.haas.berkeley.edu/bgreen people.duke.edu/∼crtaylor February 14, 2016 Abstract We study the optimal incentive scheme for a multistage project in which the agent privately observes intermediate progress. The optimal contract involves a soft deadline wherein the principal guarantees funding up to a certain date { if the agent reports progress at that date, then the principal gives him a relatively short hard deadline to complete the project { if progress is not reported at that date, then a probationary phase begins in which the project is randomly terminated at a constant rate until progress is reported. Self-reported progress plays a crucial (but non-stationary) role in implementation. We explore several variants of the model with implications for optimal project design. In particular, we show that the principal benefits by imposing a small cost on the agent in order to submit a progress report or by making the first stage of the project somewhat \harder" than the second. On the other hand, the principal does strictly worse by impairing the agent's ability to observe his own progress. JEL Classification: J41, L14, M55, D82 Keywords: Dynamic contract, Progress Report, Soft Deadline, Milestones, R&D ∗We are grateful to Bruno Biais, Simon Board, Alessandro Bonatti, Barney Hartman-Glaser, R. Vijay Krishna, John Morgan, Sofia Moroni, Steve Tadelis,