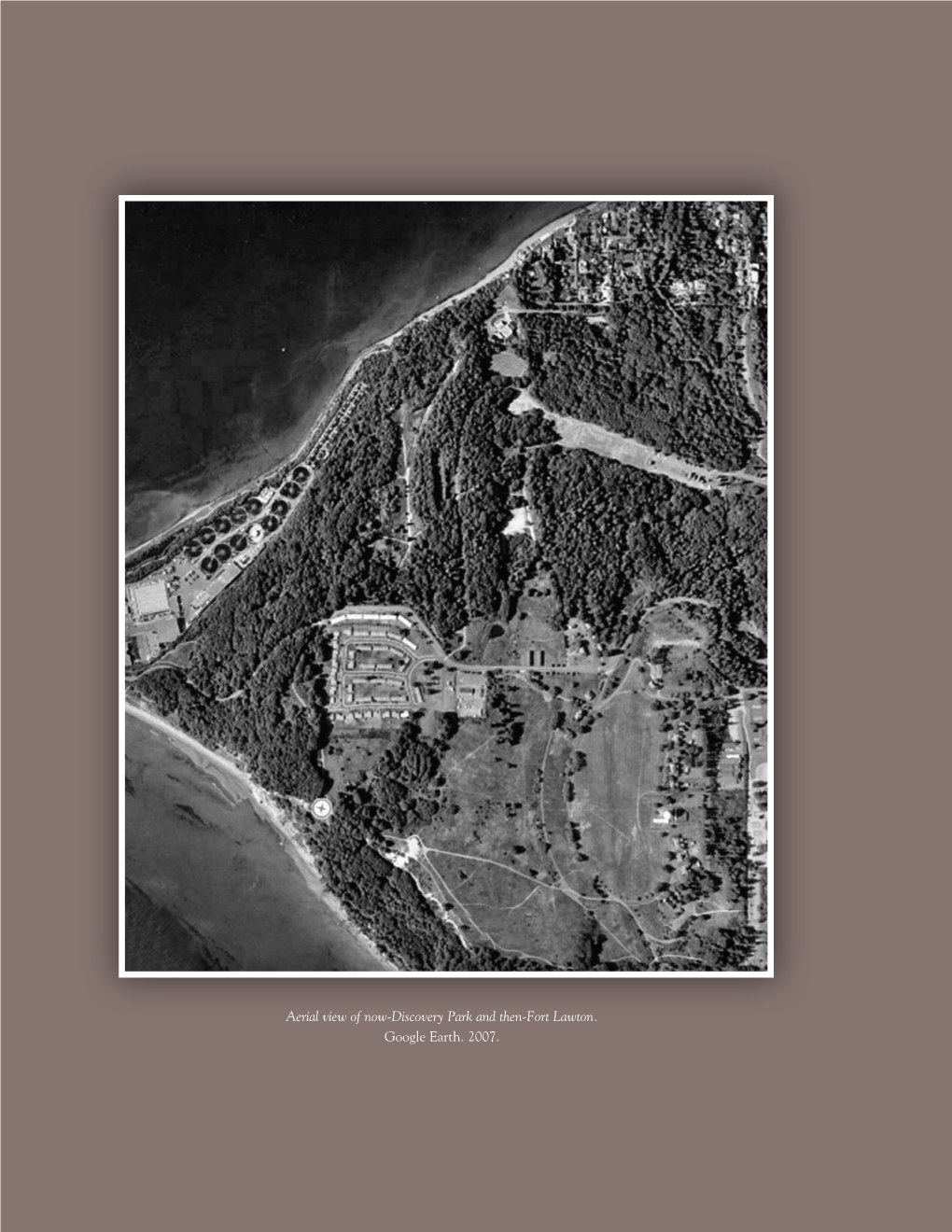

FORT LAWTON O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seattle: Queen City of the Pacific Orn Thwest Anonymous

University of Mississippi eGrove Haskins and Sells Publications Deloitte Collection 1978 Seattle: Queen city of the Pacific orN thwest Anonymous James H. Karales Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/dl_hs Part of the Accounting Commons, and the Taxation Commons Recommended Citation DH&S Reports, Vol. 15, (1978 autumn), p. 01-11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Deloitte Collection at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Haskins and Sells Publications by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ^TCAN INSTITUTE OF JC ACCOUNTANTS Queen City Seattle of the Pacific Northwest / eattle, Queen City of the Pacific Located about as far north as the upper peratures are moderated by cool air sweep S Northwest and seat of King County, corner of Maine, Seattle enjoys a moderate ing in from the Gulf of Alaska. has been termed by Harper's and other climate thanks to warming Pacific currents magazines as America's most livable city. running offshore to the west. The normal Few who reside there would disagree. To a maximum temperature in July is 75° Discussing special exhibit which they just visitor, much of the fascination of Seattle Fahrenheit, the normal minimum tempera visited at the Pacific Science Center devoted lies in the bewildering diversity of things to ture in January is 36°. Although the east to the Northwest Coast Indians are (I. to r.) do and to see, in the strong cultural and na ward drift of weather from the Pacific gives DH&S tax accountants Liz Hedlund and tional influences that range from Scandina the city a mild but moist climate, snowfall Shelley Ate and Lisa Dixon, of office vian to Oriental to American Indian, in the averages only about 8.5 inches a year, administration. -

Kirtland Kelsey Cutter, Who Worked in Spokane, Seattle and California

Kirtland Kelsey 1860-1939 Cutter he Arts and Crafts movement was a powerful, worldwide force in art and architecture. Beautifully designed furniture, decorative arts and homes were in high demand from consumers in booming new cities. Local, natural materials of logs, shingles and stone were plentiful in the west and creative architects were needed. One of them was TKirtland Kelsey Cutter, who worked in Spokane, Seattle and California. His imagination reflected the artistic values of that era — from rustic chapels and distinctive homes to glorious public spaces of great beauty. Cutter was born in Cleveland in 1860, the grandson of a distinguished naturalist. A love of nature was an essential part of Kirtland’s work and he integrated garden design and natural, local materials into his plans. He studied painting and sculp- ture in New York and spent several years traveling and studying in Europe. This exposure to art and culture abroad influenced his taste and the style of his architecture. The rural buildings of Europe inspired him throughout his career. One style associated with Cutter is the Swiss chalet, which he used for his own home in Spokane. Inspired by the homes of the Bernese Oberland region of Switzerland, it featured deep eaves that extended out from the roofline. The inside was pure Arts and Crafts, with a rustic, tiled stone fireplace, stained glass windows and elegant woodwork. Its simplicity contrasted with the grand homes many of his clients requested. The railroads brought people to the Northwest looking for opportunities in mining, logging and real estate. My great grandfather, Victor Dessert, came from France and settled in Spokane in the 1880s. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC Arctic Building AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 306 Cherry Si _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN & CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Seattle __ VICINITY OF 1 st Joel Pri tchard STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Washington 53 King 033 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC XOCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X-BUILDING(S) ^-PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED ^-COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH X-WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS _YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED XYES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: CHG Citv Center Investors # 6 STREET & NUMBER 1906 One Washington Plaza CITY, TOWN STATE ____Tacoma VICINITY OF Washington 98402 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEED^ETC. Assessors Qff| ce , King County Admi ni s trati on Buil di nq STREET & NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE Seattle Washington REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Washington State Inventory of Historic Places DATE February 1978 —FEDERAL ^STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Qff1ce Of Archaeology and Historic Preservation CITY. TOWN STATE Olympia Washington DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_ORIGINALSITE —RUINS X_ALTERED —MOVED DATE- _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Arctic Building,occupying a site at the corner of Third Avenue and Cherry Street in Seattle, rises eight stories above a ground level of retail shops to an ornate terra cotta roof cornice. -

LPB 220/21 MINUTES Landmarks Preservation Board Meeting City

LPB 220/21 MINUTES Landmarks Preservation Board Meeting City Hall Remote Meeting Wednesday May 5, 2021 - 3:30 p.m. Board Members Present Staff Dean Barnes Sarah Sodt Roi Chang Erin Doherty Jordan Kiel Melinda Bloom Kristen Johnson John Rodezno Harriet Wasserman Absent Russell Coney Matt Inpanbutr Chair Jordan Kiel called the meeting to order at 3:30 p.m. In-person attendance is currently prohibited per Washington State Governor's Proclamation No. 20-28.5. Meeting participation is limited to access by the WebEx Event link or the telephone call-in line provided on agenda. ROLL CALL 050521.1 PUBLIC COMMENT 1 Elizabeth Wales, Fairfax resident spoke in support of nomination. She said it meets the standard as an identifiable, known and cool building; the pure Gothic Revival architectural style, which is rare in Seattle; and for architect James Eustace Blackwell. She said there are many intangibles – how it feels to live here; she noted the beautiful leaded glass and said that beauty creeps into daily life. She noted the beautiful details molded into the whole. She said to please nominate the exterior of the building. She said the building is an example of handsome architecture and understated beauty for housing the middle class. She said she resists the idea that middle class and low-income housing cannot be beautiful. Ms. Wasserman joined the meeting during public comment. 050521.2 MEETING MINUTES April 7, 2021 Tabled. 050521.3 CERTIFICATES OF APPROVAL 050521.31 Rosen House 9017 Loyal Avenue NW Proposed addition and site improvements Sonya Schneider and Stuart Nagae, the property owners said they love the house and appreciate the craft and its sense of integrity. -

2019 Master Plan Update

2019 KUBOTA GARDEN MASTER PLAN UPDATE KUBOTA GARDEN 2019 MASTER PLAN UPDATE for Seattle Department of Parks & Recreation A and the Kubota Garden Foundation B C D by Jones & Jones Architects + Landscape Architects + Planners 105 South Main Street, Suite 300 E F G Seattle, Washington 98104 Cover Photo Credits: Hoshide Wanzer A. KGF Photo #339 (1976) B. Jones & Jones (2018) C. Jones & Jones (2018) D. KGF Photo #19 (1959) E. KGF Photo #259 (1962) Architects 206 624 5702 F. Jones & Jones (2018) G. Jones & Jones (2018) www.jonesandjones.com TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . 4 I. INTRODUCTION. .. .6 VI. PREFERRED CONCEPT . .. .. .. .. ..40 SUPPORT FOR THE MASTER PLAN UPDATE . .5 Need for a Master Plan Update Guiding Principles Garden Mission History: Fujitaro Kubota's Life, Inspiration, and Garden Style History: Setting the Period of Significance II. PLANNING PROCESS . .10 Necklace of Ponds Kyōryoku - Collective Effort Japanese Garden Seeking Input The Mountainside Opportunities & Issues Visitor Experience III. HISTORY OF KUBOTA GARDEN. .12 Visitor Amenities Kubota Family Wayfinding and Visitor Circulation Hierarchy Kubota Gardening Company Visitor Center Post World War II Garden Improvements Transitioning from Garden to Park IV. SITE ANALYSIS. 16 VII. IMPLEMENTATION . 65 Neighborhood Context Phasing & Implementation Visitation Staffing Mapes Creek & Natural Areas Garden Arrival APPENDIX (Separate Document) The Garden Garden History Resources Events & Programming Workshops Summary Maintenance Area Open House(s) Summary V. GARDEN NEED . .36 -

A Chronological History Oe Seattle from 1850 to 1897

A CHRONOLOGICAL HISTORY OE SEATTLE FROM 1850 TO 1897 PREPARED IN 1900 AND 1901 BT THOMAS W. PROSCH * * * tlBLS OF COIfJI'tS mm FAOE M*E PASS Prior to 1350 1 1875 225 1850 17 1874 251 1351 22 1875 254 1852 27 1S76 259 1855 58 1877 245 1854 47 1878 251 1SSS 65 1879 256 1356 77 1830 262 1357 87 1831 270 1358 95 1882 278 1859 105 1383 295 1360 112 1884 508 1861 121 1385 520 1862 i52 1886 5S5 1865 153 1887 542 1364 147 1888 551 1365 153 1883 562 1366 168 1390 577 1867 178 1391 595 1368 186 1892 407 1369 192 1805 424 1370 193 1894 441 1871 207 1895 457 1872 214 1896 474 Apostolus Valerianus, a Greek navigator in tho service of the Viceroy of Mexico, is supposed in 1592, to have discov ered and sailed through the Strait of Fuca, Gulf of Georgia, and into the Pacific Ocean north of Vancouver1 s Island. He was known by the name of Juan de Fuca, and the name was subsequently given to a portion of the waters he discovered. As far as known he made no official report of his discoveries, but he told navi gators, and from these men has descended to us the knowledge thereof. Richard Hakluyt, in 1600, gave some account of Fuca and his voyages and discoveries. Michael Locke, in 1625, pub lished the following statement in England. "I met in Venice in 1596 an old Greek mariner called Juan de Fuca, but whose real name was Apostolus Valerianus, who detailed that in 1592 he sailed in a small caravel from Mexico in the service of Spain along the coast of Mexico and California, until he came to the latitude of 47 degrees, and there finding the land trended north and northeast, and also east and south east, with a broad inlet of seas between 47 and 48 degrees of latitude, he entered therein, sailing more than twenty days, and at the entrance of said strait there is on the northwest coast thereto a great headland or island, with an exceeding high pinacle or spiral rock, like a pillar thereon." Fuca also reported find ing various inlets and divers islands; describes the natives as dressed in skins, and as being so hostile that he was glad to get away. -

Report on Designation Lpb 32/06

REPORT ON DESIGNATION LPB 32/06 Name and Address of Property: Seattle Yacht Club 1807 East Hamlin Street Legal Description: Lot 1 and the west half of Lot 2, Block 3, Montlake Park, according to plat thereof, recorded in Volume 18, page 20, in King County, Washington; together with those portions of the vacated alleys in said Block 3 which would attach by operation of law, said alleys having been vacated pursuant to City of Seattle Ordinance Numbers 89765 and 100408, a copy of the latter of which was recorded under Recording Number 7111500308. At the public meeting held on February 1, 2006, the City of Seattle's Landmarks Preservation Board voted to approve designation of the Seattle Yacht Club at 1807 E. Hamlin St. as a Seattle Landmark based upon satisfaction of the following standards for designation of SMC 25.12.350: C. It is associated in a significant way with a significant aspect of the cultural, political, or economic heritage of the community, city, state or nation. D. It embodies the distinctive visible characteristics of an architectural style, period, or of a method of construction F. Because of its prominence of spatial location, contrasts of siting, age, or scale, it is an easily identifiable visual feature of its neighborhood or the city and contributes to the distinctive quality or identity of such neighborhood or the city. DESCRIPTION Location 1807 East Hamlin Street located within the Montlake Neighborhood and partially fronting on Portage Bay in Seattle, Washington. The Seattle Yacht Club, Main Station is prominently located on a broad point on Portage Bay and can be viewed from a number of transportation corridors and public viewing points that lie to the south and west of the property. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form

IFHR-6-300 (11-78) United States Department of the Interior Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic Harvard - Belmont and/or common Harvard - Belmont District , not for publication city, town Seattle vicinity of congressional district state Washington code 53 county King code 033 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use X district public _ X-. occupied agriculture museum __ buitding(s) private unoccupied __X_ commercial park __ structure _X_both __ work in progress X educational _JL private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment ...... religious object in process yes: restricted government scientific .. w being considered X yes: unrestricted industrial transportation ^ no military __ other: name Multiple private ownerships; City of Seattle (public rlghts-of-way and open spaces) city, town vicinity of state 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. King County Administration Building Fourth Avenue at James Street city, town Seattle, state Washington 98104 6. Representation in Existing Surveys r.Seattle Inventory of Historic Resources, 1979 title 2. Office Of Urban Conservation has this property been determined elegible? _X_yes no burvey tor Proposed Landmark District date 1979-1980 federal state __ county _L local depository for survey records Office of Urban Conservation, -

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet

NPtPorm 1M004 QMf Afprwtl No. 10944011 (vvV| United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Section number ___ Page ___ SUPPLEMENTARY LISTING RECORD NRIS Reference Number: 91000782 Date Listed: 6/21/91 William Parsons House King WA Property Name County State N/A Multiple Name ^^^mm mm ^^ •» «M •» ^ ^^ ^ •»«»•» i» ^ ^ ^ •» •• ^ •»••«••• «M ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ •• «* ^ ^^ ^ ^ •• •• «M •• •• ^ ^ ^ ^ •»••••••«• ^ •••• •• ^ ^^ •• •• • This property is listed in the National Register of Historic Places in accordance with the attached nomination documentation subject to the following exceptions, exclusions, or amendments, notwithstanding the National Park Service certification included in the nomination documentation. _______________ L Signature of the Keeper Date of Action Amended Items in Nomination: Statement of Significance: Under Applicable National Register Criterion B is checked. Criterion A is removed. This information was confirmed with Leonard Garfield of the Washington State Historic Preservation Office. DISTRIBUTION: National Register property file Nominating Authority (without nomination attachment) NPS Form 10-900 (Rev. 8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places NATIONAL Registration Form REGISTER This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See Instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the Instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). -

20000 SF+ Non-Residential Multifamily Buildings

Seattle Energy Benchmarking Ordinance | 20,000 SF+ Non‐Residential Multifamily Buildings ‐ Required to Report Dec 2015 Data IMPORTANT: This list may not indicate all buildings on a parcel and/or all buildings subject to the ordinance. Building types subject to the ordinance as defined in the Director's Rule need to report, regardless of whether or not they are listed below. The Building Name, Building Address and Gross Floor Area were derived from King County Assessor records and may differ from the actual building. Please confirm the building information prior to benchmarking and email corrections to: [email protected]. SEATTLE GROSS FLOOR BUILDING NAME BUILDING ADDRESS BUILDING ID AREA (SF) 1MAYFLOWER PARK HOTEL 405 OLIVE WAY, SEATTLE, WA 98101 88,434 2 PARAMOUNT HOTEL 724 PINE ST, SEATTLE, WA 98101 103,566 3WESTIN HOTEL 1900 5TH AVE, SEATTLE, WA 98101 961,990 5HOTEL MAX 620 STEWART ST, SEATTLE, WA 98101 61,320 8WARWICK SEATTLE HOTEL 401 LENORA ST, SEATTLE, WA 98121 119,890 9WEST PRECINCT (SEATTLE POLICE) 810 VIRGINIA ST, SEATTLE, WA 98101 97,288 10 CAMLIN WORLDMARK HOTEL 1619 9TH AVE, SEATTLE, WA 98101 83,008 11 PARAMOUNT THEATER 901 PINE ST, SEATTLE, WA 98101 102,761 12 COURTYARD BY MARRIOTT ‐ ALASKA 612 2ND AVE, SEATTLE, WA 98104 163,984 13 LYON BUILDING 607 3RD AVE, SEATTLE, WA 98104 63,712 15 HOTEL MONACO 1101 4TH AVE, SEATTLE, WA 98101 153,163 16 W SEATTLE HOTEL 1112 4TH AVE, SEATTLE, WA 98101 333,176 17 EXECUTIVE PACIFIC PLAZA 400 SPRING ST, SEATTLE, WA 98104 65,009 18 CROWNE PLAZA 1113 6TH AVE, SEATTLE, WA 98101 -

Inventory -- Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMEN|l)caFrrHE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ___________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ ,NAME HISTORIC Ballard/Howe House AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 22 West Highland Drive —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Seattle VICINITY OF Ist-Congressman Joel Pritchard STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Washington 53 King 033 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC 2C.OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM JfeUILDING(S) XpRlVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X.YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED — INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY XOTHER. Steve Sarich/Lotto Construction CITY. TOWN STATE Seattle VICINITY OF Washington 98144 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDs,ETc. King County Administration Building STREET & NUMBER Fourth Avenue and James Street CITY, TOWN STATE Washington 98104 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TiTLE Seattle Landmark (Seattle City Ordinance 106348 Section 3.01) DATE February 10, 1978 —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY J4.0CAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEYREcoRosoffice of Urban Conservation, Seattle Dept. of Community Dev CITY. TOWN STATE Seattle Washington 98104 DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED JCORIGINALSITE X.GOOD —RUINS -XALTERED —MOVED DATE. —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Ballard/Howe House is a fine example of Colonial Revival, a style unusual in Seattle in such a classic form. Several very prominent Seattle architects have been associated with the house. These includes Emil deNeuf and August F. -

The Rainier Review the Official Newsletter of the Rainier Club March Letter from 2017 the Ceo

MARCH 2017 THE RAINIER REVIEW THE OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER OF THE RAINIER CLUB MARCH LETTER FROM 2017 THE CEO Art has been a central aesthetic in our LETTER FROM THE CEO.............02 Clubhouse since its early days and continues to be one of dominant program interests of our members. The Club was fortunate to have Dr. Richard Fuller as the chair of the Art NEW STAFF..................................03 Committee for so many years during his time as director of the Seattle Art Museum. While there are so many exquisite pieces to discuss in the Club’s collection, I wanted to mention NEW MEMBERS..........................03 a few artifacts by Kenneth Callahan that Dr. Fuller and other members had a hand in placing at The Rainier Club. THE PRESIDENT'S COLUMN......04 The exquisite logging scene painting from Museum and the Seattle Public Library on the Works Progress Administration (WPA) an Edward S. Curtis exhibit to celebrate era has adorned our lobby for many years Curtis’ life’s work on the 150th anniversary (see adjacent photo). Two untitled works of his birth. We expect a few pieces from the MENTOR PROGRAM.................05 located on the third floor featuring race Club’s unique platinum print collection will horses were donated to the Club by long- be part of this exhibit at SAM next year. time Arts Committee member Morris J. Separate from this event, the Foundation CULINARY ATELIER....................06 Alhadeff. The Club has been fortunate will hold a program May 10 on Edward to have a connection to so many of the Curtis to fund the acquisition of the Northwest’s artists and it’s important we republication of the 20-volume North continue to celebrate their works today.