The Linux Command Line Presentation to Linux Users of Victoria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cisco Telepresence Codec SX20 API Reference Guide

Cisco TelePresence SX20 Codec API Reference Guide Software version TC6.1 April 2013 Application Programmer Interface (API) Reference Guide Cisco TelePresence SX20 Codec D14949.03 SX20 Codec API Reference Guide TC6.1, April 2013. 1 Copyright © 2013 Cisco Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. Cisco TelePresence SX20 Codec API Reference Guide What’s in this guide? Table of Contents Introduction Using HTTP ....................................................................... 20 Getting status and configurations ................................. 20 TA - ToC - Hidden About this guide .................................................................. 4 The top menu bar and the entries in the Table of Sending commands and configurations ........................ 20 text anchor User documentation ........................................................ 4 Contents are all hyperlinks, just click on them to Using HTTP POST ......................................................... 20 go to the topic. About the API Feedback from codec over HTTP ......................................21 Registering for feedback ................................................21 API fundamentals ................................................................ 9 Translating from terminal mode to XML ......................... 22 We recommend you visit our web site regularly for Connecting to the API ..................................................... 9 updated versions of the user documentation. Go to: Password ........................................................................ -

Introduction to Linux – Part 1

Introduction to Linux – Part 1 Brett Milash and Wim Cardoen Center for High Performance Computing May 22, 2018 ssh Login or Interactive Node kingspeak.chpc.utah.edu Batch queue system … kp001 kp002 …. kpxxx FastX ● https://www.chpc.utah.edu/documentation/software/fastx2.php ● Remote graphical sessions in much more efficient and effective way than simple X forwarding ● Persistence - can be disconnected from without closing the session, allowing users to resume their sessions from other devices. ● Licensed by CHPC ● Desktop clients exist for windows, mac, and linux ● Web based client option ● Server installed on all CHPC interactive nodes and the frisco nodes. Windows – alternatives to FastX ● Need ssh client - PuTTY ● http://www.chiark.greenend.org.uk/~sgtatham/putty/download.html - XShell ● http://www.netsarang.com/download/down_xsh.html ● For X applications also need X-forwarding tool - Xming (use Mesa version as needed for some apps) ● http://www.straightrunning.com/XmingNotes/ - Make sure X forwarding enabled in your ssh client Linux or Mac Desktop ● Just need to open up a terminal or console ● When running applications with graphical interfaces, use ssh –Y or ssh –X Getting Started - Login ● Download and install FastX if you like (required on windows unless you already have PuTTY or Xshell installed) ● If you have a CHPC account: - ssh [email protected] ● If not get a username and password: - ssh [email protected] Shell Basics q A Shell is a program that is the interface between you and the operating system -

Windows Command Prompt Cheatsheet

Windows Command Prompt Cheatsheet - Command line interface (as opposed to a GUI - graphical user interface) - Used to execute programs - Commands are small programs that do something useful - There are many commands already included with Windows, but we will use a few. - A filepath is where you are in the filesystem • C: is the C drive • C:\user\Documents is the Documents folder • C:\user\Documents\hello.c is a file in the Documents folder Command What it Does Usage dir Displays a list of a folder’s files dir (shows current folder) and subfolders dir myfolder cd Displays the name of the current cd filepath chdir directory or changes the current chdir filepath folder. cd .. (goes one directory up) md Creates a folder (directory) md folder-name mkdir mkdir folder-name rm Deletes a folder (directory) rm folder-name rmdir rmdir folder-name rm /s folder-name rmdir /s folder-name Note: if the folder isn’t empty, you must add the /s. copy Copies a file from one location to copy filepath-from filepath-to another move Moves file from one folder to move folder1\file.txt folder2\ another ren Changes the name of a file ren file1 file2 rename del Deletes one or more files del filename exit Exits batch script or current exit command control echo Used to display a message or to echo message turn off/on messages in batch scripts type Displays contents of a text file type myfile.txt fc Compares two files and displays fc file1 file2 the difference between them cls Clears the screen cls help Provides more details about help (lists all commands) DOS/Command Prompt help command commands Source: https://technet.microsoft.com/en-us/library/cc754340.aspx. -

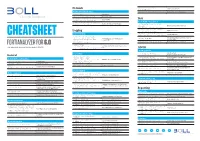

Fortianalyzer

Network diagnose fortilogd Device message rate msgrate-device Network Troubleshooting diagnose fortilogd msgrate-type Message rate for each log type execute ping [host] Ping utility execute traceroute [host] Traceroute utility diag sniffer packet <interface> Packet sniffer Disk <filter> <level> <timestamp> Disk / RAID / Virtual Disk config system fortiview settings Resolve IP address to hostname set resolve-ip enable config system locallog disk setting What happens with oldest logs set diskfull nolog / overwrite Logging diagnose system raid [option] RAID information status, hwinfo, alarms Log Forwarding diagnose system disk [option] Disk information info, health, errors, attributes CHEATSHEET config system log-forward edit log-aggregation <id> For virtual machines: provides a list of Forwarding logs to FortiAnalyzer / execute lvm info available disks aggregation-client set mode Syslog / CEF <realtime, execute lvm extend <disk nr.> For virtual machines: Add disk FORTIANALYZER FOR 6.0 aggregation, disable> config system Configure the FortiAnalyzer that receives © BOLL Engineering AG, FortiAnalyzer Cheat Sheet Version 1.1 / 08.02.2019 log-forward-service logs ADOM set accept-aggregation enable ADOM operation Log Backup config system global ADOM settings set adom-status [en/dis] Enable or disable ADOM mode General execute backup logs config system global Set ADOM mode to normal or advanced / Default device information <device name | all> for VDOMs) <ftp | sftp | scp> <server ip> Backup logs to external storage set adom-mode [normal/advanced] -

Introduction to UNIX at MSI June 23, 2015 Presented by Nancy Rowe

Introduction to UNIX at MSI June 23, 2015 Presented by Nancy Rowe The Minnesota Supercomputing Institute for Advanced Computational Research www.msi.umn.edu/tutorial/ © 2015 Regents of the University of Minnesota. All rights reserved. Supercomputing Institute for Advanced Computational Research Overview • UNIX Overview • Logging into MSI © 2015 Regents of the University of Minnesota. All rights reserved. Supercomputing Institute for Advanced Computational Research Frequently Asked Questions msi.umn.edu > Resources> FAQ Website will be updated soon © 2015 Regents of the University of Minnesota. All rights reserved. Supercomputing Institute for Advanced Computational Research What’s the difference between Linux and UNIX? The terms can be used interchangeably © 2015 Regents of the University of Minnesota. All rights reserved. Supercomputing Institute for Advanced Computational Research UNIX • UNIX is the operating system of choice for engineering and scientific workstations • Originally developed in the late 1960s • Unix is flexible, secure and based on open standards • Programs are often designed “to do one simple thing right” • Unix provides ways for interconnecting these simple programs to work together and perform more complex tasks © 2015 Regents of the University of Minnesota. All rights reserved. Supercomputing Institute for Advanced Computational Research Getting Started • MSI account • Service Units required to access MSI HPC systems • Open a terminal while sitting at the machine • A shell provides an interface for the user to interact with the operating system • BASH is the default shell at MSI © 2015 Regents of the University of Minnesota. All rights reserved. Supercomputing Institute for Advanced Computational Research Bastion Host • login.msi.umn.edu • Connect to bastion host before connecting to HPC systems • Cannot run software on bastion host (login.msi.umn.edu) © 2015 Regents of the University of Minnesota. -

Shell Variables

Shell Using the command line Orna Agmon ladypine at vipe.technion.ac.il Haifux Shell – p. 1/55 TOC Various shells Customizing the shell getting help and information Combining simple and useful commands output redirection lists of commands job control environment variables Remote shell textual editors textual clients references Shell – p. 2/55 What is the shell? The shell is the wrapper around the system: a communication means between the user and the system The shell is the manner in which the user can interact with the system through the terminal. The shell is also a script interpreter. The simplest script is a bunch of shell commands. Shell scripts are used in order to boot the system. The user can also write and execute shell scripts. Shell – p. 3/55 Shell - which shell? There are several kinds of shells. For example, bash (Bourne Again Shell), csh, tcsh, zsh, ksh (Korn Shell). The most important shell is bash, since it is available on almost every free Unix system. The Linux system scripts use bash. The default shell for the user is set in the /etc/passwd file. Here is a line out of this file for example: dana:x:500:500:Dana,,,:/home/dana:/bin/bash This line means that user dana uses bash (located on the system at /bin/bash) as her default shell. Shell – p. 4/55 Starting to work in another shell If Dana wishes to temporarily use another shell, she can simply call this shell from the command line: [dana@granada ˜]$ bash dana@granada:˜$ #In bash now dana@granada:˜$ exit [dana@granada ˜]$ bash dana@granada:˜$ #In bash now, going to hit ctrl D dana@granada:˜$ exit [dana@granada ˜]$ #In original shell now Shell – p. -

Chapter 10 SHELL Substitution and I/O Operations

Chapter 10 SHELL Substitution and I/O Operations 10.1 Command Substitution Command substitution is the mechanism by which the shell performs a given set of commands and then substitutes their output in the place of the commands. Syntax: The command substitution is performed when a command is given as: `command` When performing command substitution make sure that you are using the backquote, not the single quote character. Example: Command substitution is generally used to assign the output of a command to a variable. Each of the following examples demonstrate command substitution: #!/bin/bash DATE=`date` echo "Date is $DATE" USERS=`who | wc -l` echo "Logged in user are $USERS" UP=`date ; uptime` echo "Uptime is $UP" This will produce following result: Date is Thu Jul 2 03:59:57 MST 2009 Logged in user are 1 Uptime is Thu Jul 2 03:59:57 MST 2009 03:59:57 up 20 days, 14:03, 1 user, load avg: 0.13, 0.07, 0.15 10.2 Shell Input/Output Redirections Most Unix system commands take input from your terminal and send the resulting output back to your terminal. A command normally reads its input from a place called standard input, which happens to be your terminal by default. Similarly, a command normally writes its output to standard output, which is also your terminal by default. Output Redirection: The output from a command normally intended for standard output can be easily diverted to a file instead. This capability is known as output redirection: If the notation > file is appended to any command that normally writes its output to standard output, the output of that command will be written to file instead of your terminal: Check following who command which would redirect complete output of the command in users file. -

Bash Guide for Beginners

Bash Guide for Beginners Machtelt Garrels Garrels BVBA <tille wants no spam _at_ garrels dot be> Version 1.11 Last updated 20081227 Edition Bash Guide for Beginners Table of Contents Introduction.........................................................................................................................................................1 1. Why this guide?...................................................................................................................................1 2. Who should read this book?.................................................................................................................1 3. New versions, translations and availability.........................................................................................2 4. Revision History..................................................................................................................................2 5. Contributions.......................................................................................................................................3 6. Feedback..............................................................................................................................................3 7. Copyright information.........................................................................................................................3 8. What do you need?...............................................................................................................................4 9. Conventions used in this -

APPENDIX a Aegis and Unix Commands

APPENDIX A Aegis and Unix Commands FUNCTION AEGIS BSD4.2 SYSS ACCESS CONTROL AND SECURITY change file protection modes edacl chmod chmod change group edacl chgrp chgrp change owner edacl chown chown change password chpass passwd passwd print user + group ids pst, lusr groups id +names set file-creation mode mask edacl, umask umask umask show current permissions acl -all Is -I Is -I DIRECTORY CONTROL create a directory crd mkdir mkdir compare two directories cmt diff dircmp delete a directory (empty) dlt rmdir rmdir delete a directory (not empty) dlt rm -r rm -r list contents of a directory ld Is -I Is -I move up one directory wd \ cd .. cd .. or wd .. move up two directories wd \\ cd . ./ .. cd . ./ .. print working directory wd pwd pwd set to network root wd II cd II cd II set working directory wd cd cd set working directory home wd- cd cd show naming directory nd printenv echo $HOME $HOME FILE CONTROL change format of text file chpat newform compare two files emf cmp cmp concatenate a file catf cat cat copy a file cpf cp cp Using and Administering an Apollo Network 265 copy std input to std output tee tee tee + files create a (symbolic) link crl In -s In -s delete a file dlf rm rm maintain an archive a ref ar ar move a file mvf mv mv dump a file dmpf od od print checksum and block- salvol -a sum sum -count of file rename a file chn mv mv search a file for a pattern fpat grep grep search or reject lines cmsrf comm comm common to 2 sorted files translate characters tic tr tr SHELL SCRIPT TOOLS condition evaluation tools existf test test -

Multiping Version 3 Product Manual

MultiPing version 3 Product Manual (c) 2002, 2014 Nessoft, LLC MultiPing (c) 2002, 2014 Nessoft, LLC All rights reserved. No parts of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any means - graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or information storage and retrieval systems - without the written permission of the publisher. Products that are referred to in this document may be either trademarks and/or registered trademarks of the respective owners. The publisher and the author make no claim to these trademarks. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this document, the publisher and the author assume no responsibility for errors or omissions, or for damages resulting from the use of information contained in this document or from the use of programs and source code that may accompany it. In no event shall the publisher and the author be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damage caused or alleged to have been caused directly or indirectly by this document. Printed: August 2014 Special thanks to: Publisher All the people who contributed to this documention and to the Nessoft, LLC PingPlotter software. Managing Editor Special recognition to: Pete Ness Pierre Schwab Technical Editor Tom Larrow Jeff Murri Jenna Clara Andrea, D.D., Nina Mele Cam M. Larry M. Contents I Table of Contents Part I Welcome 2 Part II Support / Help 4 Part III Licensing 6 Part IV Getting Started 8 1 Things .t.o.. .d..o.. .w...i.t.h.. .M..u..l.t.i.P...i.n..g. -

Introduction to Unix Shell

Introduction to Unix Shell François Serra, David Castillo, Marc A. Marti- Renom Genome Biology Group (CNAG) Structural Genomics Group (CRG) Run Store Programs Data Communicate Interact with each other with us The Unix Shell Introduction Interact with us Rewiring Telepathy Typewriter Speech WIMP The Unix Shell Introduction user logs in The Unix Shell Introduction user logs in user types command The Unix Shell Introduction user logs in user types command computer executes command and prints output The Unix Shell Introduction user logs in user types command computer executes command and prints output user types another command The Unix Shell Introduction user logs in user types command computer executes command and prints output user types another command computer executes command and prints output The Unix Shell Introduction user logs in user types command computer executes command and prints output user types another command computer executes command and prints output ⋮ user logs off The Unix Shell Introduction user logs in user types command computer executes command and prints output user types another command computer executes command and prints output ⋮ user logs off The Unix Shell Introduction user logs in user types command computer executes command and prints output user types another command computer executes command and prints output ⋮ user logs off shell The Unix Shell Introduction user logs in user types command computer executes command and prints output user types another command computer executes command and prints output -

Lab Intro to Console Commands

New Lab Intro to KDE Terminal Konsole After completing this lab activity the student will be able to; Access the KDE Terminal Konsole and enter basic commands. Enter commands using a typical command line interface (CLI). Explain the use of the following commands, ls, ls –al, dir, mkdir, whoami, Explain the directory structure of a typical user. This lab activity will introduce you to one of the many command line interfaces available in Linux/UNIX operating systems and a few of the most basic commands. The command line interface you will be using for this lab activity is the console called the Konsole and is also referred to as Terminal. Note: As you notice, in the KDE system many features are written with the capital letter “K” in place of the first letter or the utility to reflect the fact it was modified for the KDE system. The original UNIX system did not use a graphical user interface GUI but rather was a command line interface (CLI) similar to the command prompt in Windows operating systems. The command line interface is referred to as a shell. Even today the command line interface (the shell) is used to issue commands on a Linux server to minimize system resources. For example, there is no need to start the GUI on the server to add a new user to an existing system. Starting the GUI will reduce the system performance because it requires RAM to run the GUI. A GUI will affect the overall performance of the server when it is supporting many users (clients).