Debbi Litt and Katie Pulles Deangela Duff Ideation and Prototyping 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dlkj;Fdslk ;Lkfdj

MoMA PRESENTS SCREENINGS OF VIDEO ART AND INTERVIEWS WITH WOMEN ARTISTS FROM THE ARCHIVE OF THE VIDEO DATA BANK Video Art Works by Laurie Anderson, Miranda July, and Yvonne Rainer and Interviews With Artists Such As Louise Bourgeois and Lee Krasner Are Presented FEEDBACK: THE VIDEO DATA BANK, VIDEO ART, AND ARTIST INTERVIEWS January 25–31, 2007 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters NEW YORK, January 9, 2007— The Museum of Modern Art presents Feedback: The Video Data Bank, Video Art, and Artist Interviews, an exhibition of video art and interviews with female visual and moving-image artists drawn from the Chicago-based Video Data Bank (VDB). The exhibition is presented January 25–31, 2007, in The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters, on the occasion of the publication of Feedback, The Video Data Bank Catalog of Video Art and Artist Interviews and the presentation of MoMA’s The Feminist Future symposium (January 26 and 27, 2007). Eleven programs of short and longer-form works are included, including interviews with artists such as Lee Krasner and Louise Bourgeois, as well as with critics, academics, and other commentators. The exhibition is organized by Sally Berger, Assistant Curator, Department of Film, The Museum of Modern Art, with Blithe Riley, Editor and Project Coordinator, On Art and Artists collection, Video Data Bank. The Video Data Bank was established in 1976 at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago as a collection of student productions and interviews with visiting artists. During the same period in the mid-1970s, VDB codirectors Lyn Blumenthal and Kate Horsfield began conducting their own interviews with women artists who they felt were underrepresented critically in the art world. -

The Kitchen Presents a New Performance by Miranda July

Press Contact: Rachael Dorsey tel: 212 255-5793 ext. 14 fax: 212 645-4258 [email protected] For Immediate Release The Kitchen presents a new performance by Miranda July New York, NY, January 3, 2007 - The Kitchen presents a new performance by filmmaker, performance artist, and writer Miranda July titled THINGS WE DON'T UNDERSTAND AND DEFINITELY ARE NOT GOING TO TALK ABOUT. This new work is a tale of heartbreak and obsession so familiar you could tell it yourself. In fact, each night July employs members of the audience to help her reveal the humor and terror that are at the heart of intimacy, betrayal, and creativity. As in her earlier productions, July utilizes video and music, and plays multiple characters. The performances will take place at The Kitchen (512 West 19th Street) on Thursday, March 1 through Sunday, March 4 at 8pm. Tickets are $15. THINGS WE DON'T UNDERSTAND AND DEFINITELY ARE NOT GOING TO TALK ABOUT, with music composed by Jon Brion (Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Punch-Drunk Love), has been performed at The Steve Allen Theater (Los Angeles) and Project Theater Artaud/San Francisco Cinematheque, and offers insight into July’s filmmaking process; her next feature film revolves around the same themes and characters. Most recently, she is best known as the writer and director of her award-winning feature length film Me and You and Everyone We Know (2005). July first received critical acclaim in New York for her performances at The Kitchen, The Swan Tool (2001) and Love Diamond (2000). About the Artist Miranda July is a filmmaker, performing artist and writer. -

Astria Suparak Is an Independent Curator and Artist Based in Oakland, California. Her Cross

Astria Suparak is an independent curator and artist based in Oakland, California. Her cross- disciplinary projects often address urgent political issues and have been widely acclaimed for their high-level concepts made accessible through a popular culture lens. Suparak has curated exhibitions, screenings, performances, and live music events for art institutions and festivals across ten countries, including The Liverpool Biennial, MoMA PS1, Museo Rufino Tamayo, Eyebeam, The Kitchen, Carnegie Mellon, Internationale Kurzfilmtage Oberhausen, and Expo Chicago, as well as for unconventional spaces such as roller-skating rinks, ferry boats, sports bars, and rock clubs. Her current research interests include sci-fi, diasporas, food histories, and linguistics. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE (selected) . Independent Curator, 1999 – 2006, 2014 – Present Suparak has curated exhibitions, screenings, performances, and live music events for art, film, music, and academic institutions and festivals across 10 countries, as well as for unconventional spaces like roller-skating rinks, ferry boats, elementary schools, sports bars, and rock clubs. • ART SPACES, BIENNIALS, FAIRS (selected): The Kitchen, MoMA PS1, Eyebeam, Participant Inc., Smack Mellon, New York; The Liverpool Biennial 2004, FACT (Foundation for Art and Creative Technology), England; Museo Rufino Tamayo Arte Contemporaneo, Mexico City; Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco; Museum of Photographic Arts, San Diego; FotoFest Biennial 2004, Houston; Space 1026, Vox Populi, Philadelphia; National -

Hunger Makes Me a Modern Girl: a Memoir Free

FREE HUNGER MAKES ME A MODERN GIRL: A MEMOIR PDF Carrie Brownstein | 256 pages | 05 Nov 2015 | Little, Brown Book Group | 9780349007922 | English | London, United Kingdom Hunger Makes Me a Modern Girl by Carrie Brownstein: | : Books Look Inside. Oct 27, Minutes Buy. Before Carrie Brownstein became a music icon, she was a young girl growing up in the Pacific Northwest just as it was becoming the setting for one the most important movements in rock history. Seeking a sense of home and identity, she would discover both while moving from spectator to creator in experiencing the power and mystery of a live performance. With Sleater-Kinney, Brownstein and her bandmates rose to prominence in the burgeoning underground feminist punk-rock movement that would define music and pop culture in the s. With deft, lucid prose Brownstein proves herself as formidable on the page as on the stage. That quality has become obvious over the course of eight albums with bandmates Corin Tucker and Janet Weiss… and now in her refreshingly forthright new memoir, Hunger Makes Me a Modern Girl. Instead, she candidly recounts the panic attacks and stress-induced shingles she experienced on tour. More important, it shows how compelling she is when she opens up. She carries a lot of humor and gentle self-deprecation throughout the work. For Carrie Brownstein, who grew up in the Riot Grrrl movement in the Pacific Northwest, they did: She started out playing in countless punk bands until settling on one with her BFF and romantic partner, Corin Tucker, which they eventually turned into the best rock band of all time, Sleater-Kinney. -

SEPTEMBER 2018 COMPLIMENTARY GUIDE Catskillregionguide.Com

Catskill Mountain Region SEPTEMBER 2018 COMPLIMENTARY GUIDE catskillregionguide.com SPECIAL SECTION: VISIT DELAWARE COUNTY! September 2018 • GUIDE 1 2 • www.catskillregionguide.com CONTENTS OF TABLE www.catskillregionguide.com VOLUME 33, NUMBER 9 September 2018 PUBLISHERS Peter Finn, Chairman, Catskill Mountain Foundation Sarah Finn, President, Catskill Mountain Foundation EDITORIAL DIRECTOR, CATSKILL MOUNTAIN FOUNDATION Sarah Taft ADVERTISING SALES Barbara Cobb Steve Friedman CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Heather Rolland, Jeff Senterman & Robert Tomlinson ADMINISTRATION & FINANCE Candy McKee Justin McGowan & Isabel Cunha On the cover: Photo by Elizabeth Hall Dukin PRINTING Catskill Mountain Printing Services 4 WOODSTOCK-NEW PALTZ ART & CRAFTS FAIR DISTRIBUTION Catskill Mountain Foundation 6 MOUNTAIN TOP ARBORETUM: Labor Day Events and New Timber Frame Education Center EDITORIAL DEADLINE FOR NEXT ISSUE: September 10 The Catskill Mountain Region Guide is published 12 times a year 10 WATERSHED AGRICULTURAL COUNCIL: Celebrating 25 by the Catskill Mountain Foundation, Inc., Main Street, PO Box 924, Hunter, NY 12442. If you have events or programs that you Years of Supporting the Region’s Farm and Forest Owners would like to have covered, please send them by e-mail to tafts@ catskillmtn.org. Please be sure to furnish a contact name and in- clude your address, telephone, fax, and e-mail information on all VISIT DELAWARE COUNTY: correspondence. For editorial and photo submission guidelines 12 send a request via e-mail to [email protected]. The Heart of the Great Western Catskills The liability of the publisher for any error for which it may be held legally responsible will not exceed the cost of space ordered or occupied by the error. -

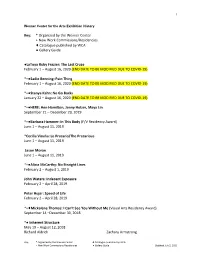

Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center + New Work Commissions/Residencies ♦ Catalogue Published by WCA ● Gallery Guide

1 Wexner Center for the Arts Exhibition History Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center + New Work Commissions/Residencies ♦ Catalogue published by WCA ● Gallery Guide ●LaToya Ruby Frazier: The Last Cruze February 1 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●Sadie Benning: Pain Thing February 1 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●Stanya Kahn: No Go Backs January 22 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●HERE: Ann Hamilton, Jenny Holzer, Maya Lin September 21 – December 29, 2019 *+●Barbara Hammer: In This Body (F/V Residency Award) June 1 – August 11, 2019 *Cecilia Vicuña: Lo Precario/The Precarious June 1 – August 11, 2019 Jason Moran June 1 – August 11, 2019 *+●Alicia McCarthy: No Straight Lines February 2 – August 1, 2019 John Waters: Indecent Exposure February 2 – April 28, 2019 Peter Hujar: Speed of Life February 2 – April 28, 2019 *+♦Mickalene Thomas: I Can’t See You Without Me (Visual Arts Residency Award) September 14 –December 30, 2018 *● Inherent Structure May 19 – August 12, 2018 Richard Aldrich Zachary Armstrong Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center ♦ Catalogue published by WCA + New Work Commissions/Residencies ● Gallery Guide Updated July 2, 2020 2 Kevin Beasley Sam Moyer Sam Gilliam Angel Otero Channing Hansen Laura Owens Arturo Herrera Ruth Root Eric N. Mack Thomas Scheibitz Rebecca Morris Amy Sillman Carrie Moyer Stanley Whitney *+●Anita Witek: Clip February 3-May 6, 2018 *●William Kentridge: The Refusal of Time February 3-April 15, 2018 All of Everything: Todd Oldham Fashion February 3-April 15, 2018 Cindy Sherman: Imitation of Life September 16-December 31, 2017 *+●Gray Matters May 20, 2017–July 30 2017 Tauba Auerbach Cristina Iglesias Erin Shirreff Carol Bove Jennie C. -

Live Wire Radio Pacific Northwest Friends: $2,500 to $4,999

LIVE WIRE SPONSORSHIP DECK 2020 AN INCREDIBLE PARTNERSHIP ON-THE-AIR WITH LIVE WIRE High-Quality, Engaged, Clutter-Free & National & Distinctive Influential & Trusted Multi-Channel Programming Culturally-Minded Messaging Opportunities Audience Platform LIVE WIRE IT’S LATE NIGHT FOR RADIO Hosted by Luke Burbank, Live Wire combines the prestige of national radio broadcasting with its own outstanding reputation as an independently-produced Portland production. Over the last 16 years, Live Wire has brought audiences together to spark moments of human connectedness through performance, humor, and unpredictable moments of discovery. Live Wire is music, comedy, and conversation. Our show stands out as one of the fastest growing entertainment radio programs on air today. Listeners turn to Live Wire every week to laugh, learn, and feel the nation’s cultural pulse. It’s Late Night for Radio. THE VOICES OF LIVE WIRE FEATURED GUESTS MUSIC: Jeff Tweedy, Pink Martini, Melissa Etheridge, Little Freddie King, Patterson Hood, Kishi Bashi, Mandy Moore, Thundercat, Shakey Graves, Neko Case, Shovels & Rope, Thao and the Get Down Stay Down, Loudon Wainwright III, Waxahatchee, Blitzen Trapper, Amythyst Kiah, and Reggie Watts HOST LUKE COMEDY: Abbi Jacobson, Janeane Garofalo, Marc BURBANK Maron, Phoebe Robinson, John Hodgman, Hari Kondabolu, Paula Poundstone, Thomas Middleditch, Luke Burbank grew up one of seven Ben Schwartz, Reggie Watts, Mo Rocca, Kristen kids, learning early on how to vie for Schaal, Carrie Brownstein, and Fred Armisen attention. Those profound childhood issues have propelled him to contribute to and create various media projects, CONVERSATION: Salman Rushdie, W. Kamau Bell, including Wait Wait...Don’t Tell Me, This Lindy West, Jesse Eisenberg, Ijeoma Oluo, John Irving, American Life, CBS Sunday Morning, Diana Nyad, Eileen Myles, Jonathan Safran Foer, Luis and the daily podcast Too Beautiful to Live. -

<<< Peter Max Lawrence >>>

Peter Max Lawrence [email protected] petermaxlawrence.com SOLO EXHIBITIONS Return of the Yeti, Subrosa Space, Athens, Greece, 2018 The Umpire Strikes Back, Subrosa Space, Athens, Greece, 2018 Beyond Say, Subrosa Space, Athens, Greece, 2018 October Surprise, Jernquist Studio, Brooklyn, NY 2016 In With The Old & Out With The New - New Lofts Art Gallery, Stockton, KS 2015 iNtheStudioAgain&Again&again, one2one, Lucas, KS 2014 Sell Out | Spikes, San Francisco, CA 2013 The Indelible Sulk | Mission: Comics & Art, San Francisco, CA 2013 Magickal Marvels: Ethos, Mythos, and Pathos | James C. Hormel LGBT Center - San Francisco Public Library 2012 The Ghost Show | Gallerí Klósett | Reykjavík, Iceland 2012 At War: Truong Tran & Peter Max Lawrence | SOMArts, San Francisco, CA 2012 Here Comes The Rain | Her Majesty's Secret Beekeeper, San Francisco CA 2011 Prey for Them | Little Bird, San Francisco CA 2011 The Paper Trail | Whiskey Thieves, San Francisco, CA 2010 The Sweet Stink of Stigma, Magnet, San Francisco, CA, 2010 Midnight Moth & Bug Issue #1 vol.3, The Tiny Gallery | Big Think Studios, San Francisco CA 2009 The Innocent Culprit | Whiskey Thieves, San Francisco, CA , 2007 Addicted to Applause | Diego Rivera Gallery, San Francisco, CA , 2007 Contemporary Dilemmas for the Ancient Gods | Magnet, San Francisco, CA, 2006 The Woman of Willendorf and Worldy other Wonders | The Austin Law Group, San Francisco, CA , 2006 Art Span, Open Studios, San Francisco, CA, 2006 Sacred Monsters | Leedy-Voulkos -

Craftivist Clay: Resistance and Activism in Contemporary Ceramics

Craftivist Clay: Resistance and Activism in Contemporary Ceramics by Mary Callahan Baumstark A thesis presented to OCAD University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in CONTEMPORARY ART, DESIGN, AND NEW MEDIA ART HISTORIES Toronto, Ontario, Canada, April, 2016 ©Mary Callahan Baumstark 2016 ii Author's Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize OCAD University to lend this thesis to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. I further authorize OCAD University to reproduce this thesis by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. iii Abstract Craftivist Clay: Resistance and Activism in Contemporary Ceramics Mary Callahan Baumstark Master of Arts in Contemporary Art, Design, and New Media Histories OCAD University April 2016 Since the late twentieth century, the social engagement of craft emerged as a primary concern for both makers and activists. While “craftivism” was quickly defined by the work of a few, this thesis expands previous considerations of craftivism as both theoretical construct and making method. Considering the emergence of craftivism as method, this paper examines the work of ceramic craftivists, analyzing their practices and produced works within a context of increased political urgency, using ceramics as a microcosmic exploration for craftivism in a given craft media. -

February 1999

alpha tech C 0 M P ·UTE R 5 671-2334 2300 James St. Bellingham, WA 98225 www.alphatechcomputers.com Cream Ware transforms ~our Winaows PC into ani~n ~ertormance, multitracK ai~ital auaio recorain~, eaitin~ ana masterin~ worKstation witn ultra fast ~. ~·bit Si~nal ~rOC9SSin~ Ca~acit~. Desi~nea lor com~lete ai~ital music ~roaution, CreamWare consists ol ootn naraware ana its own versatile auaio wo~station software· offenn~ acom~lete solution, not just a~artial ste~. Eait mulntrac~ arran~ements on ~our nara arive witn CreamWare · rrom 2to 12~ trac~s ana more ae~enain~ on ~our PC/CreamWare con~~uration. Process effects to trac~s ana sauna files !rom aso~nisticatea suite ol Pentium oasea DSP ~lters ana effects, re~lacin~ rac~s ol ex~ensive outooara ~ear, all in real time witn no wa~in~ lor tne s~stem to calculate ana a~~~~. rull~ automatea mixin~ tnat incluaes: volume curves, cross laaes, unlimrrea non~estrucnve eaitin~ ana almost an~nin~ else ~ou've ever areamea aoout navin~ at ~our ais~osal at ONE TENTH THE COST , ~our own cas! creamw@re© • 4in /4 out (32 tracks apporx. ) • 16 in /16 out (64 tracks approx.) • Optical, S/PDIF &MIDI I/O • 2ADAT Optical, ADAT 9-pin Sync, BNC, $225 50 $14Q.gQnth 161\0 ND DIA Converter TRS, Monitor Out 'per month • Wave Walkers DSP Suite • WaveWalkers, FireWalkers DSP Suites & • Near Field Monitors w/ Apmlifier Osiris DSP I Mastering I Finalizing Suite • 12 Channel Mixer/Microphone Preamplifier • Mid Field Monitors w/ Apmlifier • Merit Pentium 11266 MidTower ·64MB RAM •8.4GB Hard Drive • 16/32 Channel Recording Console w/lnline Monitor 36x CDROM ·16x4x4 CDRW, 56k Modem -8MB Video RAM • Merit Pentium 11266 MidTower ·128MB RAM ·10.2GB Hard Drive 40x CDROM ·16x4x4 CDRW · 56k Modem- 8MB Video RAM 15" SVGA, Win 98 · MS Works 17' SVGA, Win 98 · MS Works ._... -

AUTUMN 2018 ART ARCHITECTURE DESIGN PHOTOGRAPHY Detail from Anna Atkins, Dictyota Dichotoma, in the Young State; and in Fruit, C

AUTUMN 2018 ART ARCHITECTURE DESIGN PHOTOGRAPHY Detail from Anna Atkins, Dictyota dichotoma, in the young state; and in fruit, c. 1849, Cyanotype, 10.5 x 8.25 in. / 26.5 x 21 cm, Spencer Collection, The New York Public Library From Sun Gardens: The Cyanotypes of Anna Atkins ( see page 45) ART FASHION 50 ART MOVEMENTS YOU SHOULD KNOW: FROM IMPRESSIONISM TO PERFORMANCE ART 21 CONTEMPORARY MUSLIM FASHION 36 A YEAR IN IMPRESSIONISM 2-3 EAST MEETS WEST: JEWELS OF THE MAHARAJAS FROM THE AL THANI COLLECTION 37 BEFORE THE FALL: GERMAN AND AUSTRIAN ART IN THE 1930S 23 GIOVANNI BELLINI: THE ART OF CONTEMPLATION 5 FOOD AND DRINK BLIND FAITH: BETWEEN THE VISCERAL AND THE COGNITIVE IN CONTEMPORARY ART 31 FREE THE TIPPLE: KICKASS COCKTAILS INSPIRED BY ICONIC WOMEN 7 COLOR AND LIGHT: THE NEO-IMPRESSIONIST HENRI-EDMOND CROSS 25 WILD: ADVENTURE COOKBOOK 8 WILLIAM CORDOVA: NOW’S THE TIME: NARRATIVES OF SOUTHERN ALCHEMY 49 NORTH WILD KITCHEN: HOME COOKING FROM THE HEART OF NORWAY 9 ENRICO DAVID: GRADATIONS OF SLOW RELEASE 50 WILLIAM FORSYTHE: CHOREOGRAPHIC OBJECTS 48 PHOTOGRAPHY HENRY FUSELI: DRAMA AND THEATRE 27 100 GREAT STREET PHOTOGRAPHS 6 GAUGUIN: A SPIRITUAL JOURNEY 39 CONGO TALES: TOLD BY THE PEOPLE OF MBOMO 29 JEFFREY GIBSON: THIS IS THE DAY 46 FASHION IMAGE REVOLUTION 16 ALEXANDER VON HUMBOLDT: THE COMPLETE DRAWINGS FROM THE AMERICAN TRAVEL DIARIES 4 GREAT ENGLISH INTERIORS 13 I WAS RAISED ON THE INTERNET 51 STEVE KAHN: THE HOLLYWOOD SUITES 44 JITISH KALLAT 28 DOROTHEA LANGE: POLITICS OF SEEING 14-15 ERNST LUDWIG KIRCHNER: IMAGINARY TRAVELS 26 -

Miranda July

MIRANDA JULY MIRANDA JULY Prestel Munich London New York 8 Conversation between Miranda July and Julia Bryan-Wilson WORKS 1992–2020 26 THE LIFERS + MORE PLAYS 78 THE SWAN TOOL 32 SNARLA 84 THE DRIFTERS 39 BANDS 88 NO ONE BELONGS HERE MORE THAN YOU 42 EARLY PERFORMANCES 93 ME AND YOU AND 49 BIG MISS MOVIOLA / EVERYONE WE KNOW JOANIE 4 JACKIE 104 THINGS WE DON’T 57 SHORT FILMS UNDERSTAND AND 62 SHOES DEFINITELY ARE NOT GOING TO TALK ABOUT 66 LOVE DIAMOND 110 WINDOW SHADE FOR 73 LEARNING TO THE THING LOVE YOU MORE 112 THE AUCTION 114 THE HALLWAY 186 RIPPED POSTER 118 ELEVEN HEAVY THINGS 188 ARTANGEL AND MIRANDA JULY PRESENT 128 EXTRAS NORWOOD JEWISH 134 THE FUTURE C H A R I T Y S H O P, THE LONDON BUDDHIST 146 IT CHOOSES YOU CENTRE CHARITY SHOP & 150 WE THINK ALONE SPITALFIELDS CRYPT TRUST CHARITY SHOP 156 THE FIRST BAD MAN IN SOLIDARITY WITH 162 SOMEBODY ISLAMIC RELIEF CHARITY SHOP AT SELFRIDGES 170 NEW SOCIETY 198 I’M THE PRESIDENT, 178 MAY 14, 2016 BABY BY PAUL FORD AND MIRANDA JULY 202 KAJILLIONAIRE 215 Index 221 Acknowledgments 223 Photo credits For Lindy and Rich CONVERSATION BETWEEN MIRANDA JULY AND JULIA BRYAN-WILSON Miranda and I met in 1996 when we were both living in Portland, Oregon. I was cocurating a video show at the warehouse of the queercore music label Candy Ass Records. Miranda had come to spread the word about her newly hatched feminist video chain letter. But when Miranda saw me seated on the ground madly trying to assemble my overly ambitious xeroxed catalogues for the show, she sat right down and started gluing.