I Like Working Here Because of the Bigness — the Big Spaces, the Big Timber

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dlkj;Fdslk ;Lkfdj

MoMA PRESENTS SCREENINGS OF VIDEO ART AND INTERVIEWS WITH WOMEN ARTISTS FROM THE ARCHIVE OF THE VIDEO DATA BANK Video Art Works by Laurie Anderson, Miranda July, and Yvonne Rainer and Interviews With Artists Such As Louise Bourgeois and Lee Krasner Are Presented FEEDBACK: THE VIDEO DATA BANK, VIDEO ART, AND ARTIST INTERVIEWS January 25–31, 2007 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters NEW YORK, January 9, 2007— The Museum of Modern Art presents Feedback: The Video Data Bank, Video Art, and Artist Interviews, an exhibition of video art and interviews with female visual and moving-image artists drawn from the Chicago-based Video Data Bank (VDB). The exhibition is presented January 25–31, 2007, in The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters, on the occasion of the publication of Feedback, The Video Data Bank Catalog of Video Art and Artist Interviews and the presentation of MoMA’s The Feminist Future symposium (January 26 and 27, 2007). Eleven programs of short and longer-form works are included, including interviews with artists such as Lee Krasner and Louise Bourgeois, as well as with critics, academics, and other commentators. The exhibition is organized by Sally Berger, Assistant Curator, Department of Film, The Museum of Modern Art, with Blithe Riley, Editor and Project Coordinator, On Art and Artists collection, Video Data Bank. The Video Data Bank was established in 1976 at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago as a collection of student productions and interviews with visiting artists. During the same period in the mid-1970s, VDB codirectors Lyn Blumenthal and Kate Horsfield began conducting their own interviews with women artists who they felt were underrepresented critically in the art world. -

The Kitchen Presents a New Performance by Miranda July

Press Contact: Rachael Dorsey tel: 212 255-5793 ext. 14 fax: 212 645-4258 [email protected] For Immediate Release The Kitchen presents a new performance by Miranda July New York, NY, January 3, 2007 - The Kitchen presents a new performance by filmmaker, performance artist, and writer Miranda July titled THINGS WE DON'T UNDERSTAND AND DEFINITELY ARE NOT GOING TO TALK ABOUT. This new work is a tale of heartbreak and obsession so familiar you could tell it yourself. In fact, each night July employs members of the audience to help her reveal the humor and terror that are at the heart of intimacy, betrayal, and creativity. As in her earlier productions, July utilizes video and music, and plays multiple characters. The performances will take place at The Kitchen (512 West 19th Street) on Thursday, March 1 through Sunday, March 4 at 8pm. Tickets are $15. THINGS WE DON'T UNDERSTAND AND DEFINITELY ARE NOT GOING TO TALK ABOUT, with music composed by Jon Brion (Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Punch-Drunk Love), has been performed at The Steve Allen Theater (Los Angeles) and Project Theater Artaud/San Francisco Cinematheque, and offers insight into July’s filmmaking process; her next feature film revolves around the same themes and characters. Most recently, she is best known as the writer and director of her award-winning feature length film Me and You and Everyone We Know (2005). July first received critical acclaim in New York for her performances at The Kitchen, The Swan Tool (2001) and Love Diamond (2000). About the Artist Miranda July is a filmmaker, performing artist and writer. -

Astria Suparak Is an Independent Curator and Artist Based in Oakland, California. Her Cross

Astria Suparak is an independent curator and artist based in Oakland, California. Her cross- disciplinary projects often address urgent political issues and have been widely acclaimed for their high-level concepts made accessible through a popular culture lens. Suparak has curated exhibitions, screenings, performances, and live music events for art institutions and festivals across ten countries, including The Liverpool Biennial, MoMA PS1, Museo Rufino Tamayo, Eyebeam, The Kitchen, Carnegie Mellon, Internationale Kurzfilmtage Oberhausen, and Expo Chicago, as well as for unconventional spaces such as roller-skating rinks, ferry boats, sports bars, and rock clubs. Her current research interests include sci-fi, diasporas, food histories, and linguistics. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE (selected) . Independent Curator, 1999 – 2006, 2014 – Present Suparak has curated exhibitions, screenings, performances, and live music events for art, film, music, and academic institutions and festivals across 10 countries, as well as for unconventional spaces like roller-skating rinks, ferry boats, elementary schools, sports bars, and rock clubs. • ART SPACES, BIENNIALS, FAIRS (selected): The Kitchen, MoMA PS1, Eyebeam, Participant Inc., Smack Mellon, New York; The Liverpool Biennial 2004, FACT (Foundation for Art and Creative Technology), England; Museo Rufino Tamayo Arte Contemporaneo, Mexico City; Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco; Museum of Photographic Arts, San Diego; FotoFest Biennial 2004, Houston; Space 1026, Vox Populi, Philadelphia; National -

Oral History Interview with Guy Anderson, 1983 February 1-8

Oral history interview with Guy Anderson, 1983 February 1-8 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Interview This transcript is in the public domain and may be used without permission. Quotes and excerpts must be cited as follows: Oral history interview with Guy Anderson, 1983 February 1-8, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Oral History Interview with Guy Anderson Conducted by Martha Kingsbury At La Conner, Washington 1983 February 1 & 8 GA: GUY ANDERSON MK: MARTHA KINGSBURY [Part 1] GA: Now that it is spring and February and I suppose it's a good time to talk about great things. I know the sun's out, the caterpillars and things coming out soon; but talking about the art scene, I have been reading a very interesting thing that was sent to me, once again, by Wesley Wehrÿ-- the talk that Henry Geldzahler gave to Yale, I think almost a year ago, about what he felt about the state of the New York scene, and the scene of art, generally speaking in the world. He said some very cogent things all through it, things that I think probably will apply for quite a long time, particularly to those people and a lot of young people who are so interested in the arts. Do you want to see that? MK: Sure. [Break in tape] MK: Go ahead. -

Modernism in the Pacific Northwest: the Mythic and the Mystical June 19 — September 7, 2014

Ann P. Wyckoff Teacher Resource Center Educator Resource List Modernism in the Pacific Northwest: The Mythic and the Mystical June 19 — September 7, 2014 BOOKS FOR STUDENTS A Community of Collectors: 75th Anniversary Gifts to the Seattle Art Museum. Chiyo Ishikawa, ed. Seattle: Seattle Adventures in Greater Puget Sound. Dawn Ashbach and Art Museum, 2008. OSZ N 745 S4 I84 Janice Veal. Anacortes, WA: Northwest Island Association, 1991. QH 105 W2 A84 Overview of recent acquisitions to SAM’s collection, including works by Northwest artists. Educational guide and activity book that explores the magic of marine life in the region. George Tsutakawa. Martha Kingsbury. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1990. N 6537 T74 A4 Ancient Ones: The World of the Old–Growth Douglas Fir. Barbara Bash. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books for Exhibition catalogue covering 60 years of work of the Children, 2002. QK 494.5 P66 B37 Seattle–born painter, sculptor, and fountain maker. Traces the life cycle of the Douglas fir and the old–growth Kenneth Callahan. Thomas Orton and Patricia Grieve forest and their intricate web of life. Watkinson. Seattle : University of Washington Press; 2000. ND 237 C3 O77 Larry Gets Lost in Seattle. John Skewes. Seattle: Sasquatch Books, 2007. F 899 S44 S5 Overview of the life and work of artist Kenneth Callahan. Pete looks for his dog Larry in Seattle’s famous attractions. Margaret Callahan: Mother of Northwest Art. Margaret Bundy Callahan and Brian Tobey Callahan, ed. Victoria, S Is for Salmon: A Pacific Northwest Alphabet. Hannah BC: Trafford Publising, 2009. ND 237 C19 C35 Viano. -

The Galleries

THE GALLERIES ART at the convention center A SELF-GUIDED TOUR Enriching Your Visit: Taking the Tour The Public Art Program Washington State Convention Center features approximately The Washington State Convention Center (WSCC) public 100 works of art on public display around four levels of its North and South Gallerias. Several other works are located in art program, perhaps the largest of its kind in the nation, its office and convention lobby areas. Areas of the facility that was established to provide an environment that enriches may not be available to the public due to convention- the experience of all who visit the meeting facility. With well related activities are clearly noted. over 100 works on display, art has been a popular feature since the facility opened in 1988. Initially, art was incorporated into This self-guided, self-paced tour booklet was designed to the original building design with assistance from the state’s direct you to the many different areas where artworks are cur- Percent for the Arts Program. Since then, due to a commit- rently on display. A few of the works listed inthis booklet are ment to provide civic benefits to our community, the WSCC has located outside of the WSCC. offered an ever-changing collection, readily accessible at no This self-tour begins on Level 1 just south of the Convention charge to meeting attendees and the general public. Place entrance. The indicated route will direct you back to the south escalators for easy access to the next level. All areas of In 1997, the board established the WSCC Art Foundation at this tour are also accessible by elevator. -

The New York Botanical Garden

Vol. XV DECEMBER, 1914 No. 180 JOURNAL The New York Botanical Garden EDITOR ARLOW BURDETTE STOUT Director of the Laboratories CONTENTS PAGE Index to Volumes I-XV »33 PUBLISHED FOR THE GARDEN AT 41 NORTH QUBKN STRHBT, LANCASTER, PA. THI NEW ERA PRINTING COMPANY OFFICERS 1914 PRESIDENT—W. GILMAN THOMPSON „ „ _ i ANDREW CARNEGIE VICE PRESIDENTS J FRANCIS LYNDE STETSON TREASURER—JAMES A. SCRYMSER SECRETARY—N. L. BRITTON BOARD OF- MANAGERS 1. ELECTED MANAGERS Term expires January, 1915 N. L. BRITTON W. J. MATHESON ANDREW CARNEGIE W GILMAN THOMPSON LEWIS RUTHERFORD MORRIS Term expire January. 1916 THOMAS H. HUBBARD FRANCIS LYNDE STETSON GEORGE W. PERKINS MVLES TIERNEY LOUIS C. TIFFANY Term expire* January, 1917 EDWARD D. ADAMS JAMES A. SCRYMSER ROBERT W. DE FOREST HENRY W. DE FOREST J. P. MORGAN DANIEL GUGGENHEIM 2. EX-OFFICIO MANAGERS THE MAYOR OP THE CITY OF NEW YORK HON. JOHN PURROY MITCHEL THE PRESIDENT OP THE DEPARTMENT OP PUBLIC PARES HON. GEORGE CABOT WARD 3. SCIENTIFIC DIRECTORS PROF. H. H. RUSBY. Chairman EUGENE P. BICKNELL PROF. WILLIAM J. GIES DR. NICHOLAS MURRAY BUTLER PROF. R. A. HARPER THOMAS W. CHURCHILL PROF. JAMES F. KEMP PROF. FREDERIC S. LEE GARDEN STAFF DR. N. L. BRITTON, Director-in-Chief (Development, Administration) DR. W. A. MURRILL, Assistant Director (Administration) DR. JOHN K. SMALL, Head Curator of the Museums (Flowering Plants) DR. P. A. RYDBERG, Curator (Flowering Plants) DR. MARSHALL A. HOWE, Curator (Flowerless Plants) DR. FRED J. SEAVER, Curator (Flowerless Plants) ROBERT S. WILLIAMS, Administrative Assistant PERCY WILSON, Associate Curator DR. FRANCIS W. PENNELL, Associate Curator GEORGE V. -

The Juilliard School

NEW ISSUE — BOOK-ENTRY ONLY Ratings: Moody’s: Aa2 S&P: AA See “RATINGS” herein In the opinion of Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe LLP, Bond Counsel, based upon an analysis of existing laws, regulations, rulings and court decisions, and assuming, among other matters, the accuracy of certain representations and compliance with certain covenants, interest on the Series 2018A Bonds (as such term is defined below) is excluded from gross income for federal income tax purposes under Section 103 of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986. In the further opinion of Bond Counsel, interest on the Series 2018A Bonds is not a specific preference item for purposes of the federal alternative minimum tax. Bond Counsel is also of the opinion that interest on the Series 2018A Bonds is exempt from personal income taxes imposed by the State of New York or any political subdivision thereof (including The City of New York). Bond Counsel expresses no opinion regarding any other tax consequences related to the ownership or disposition of, or the amount, accrual or receipt of interest on, the Series 2018A Bonds. See “TAX MATTERS” herein. $42,905,000 THE TRUST FOR CULTURAL RESOURCES OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK Refunding Revenue Bonds, Series 2018A (The Juilliard School) The Refunding Revenue Bonds, Series 2018A (The Juilliard School) (the “Series 2018A Bonds”) will be issued and secured under the Revenue Bond Resolution (The Juilliard School), adopted by The Trust for Cultural Resources of The City of New York (the “Trust”), as of March 18, 2009, as supplemented, including as supplemented by a Series 2018A Resolution Authorizing not in Excess of $50,000,000 Refunding Revenue Bonds, Series 2018A (The Juilliard School), adopted by the Trust on October 11, 2018 (collectively, the “Resolution”). -

Northwest Matriarchs of Modernism

Northwest Matriarchs of Modernism 12 Proto-feminists from Oregon and Washington Mary Henry Pansynclastic Riddle 1966, 48 x 61.5 Courtesy of the Artist and Bryan Ohno Gallery Cover photo: Hilda Morris in her studio 1964 Photo: Hiro Moriyasu Northwest Matriarchs of Modernism Organized by The Art Gym, Marylhurst University 12 Proto-feminists from Oregon and Washington with support from the Regional Arts and Culture Council, the Lamb Foundation, members and friends. The Art Gym, Marylhurst University, Marylhurst, Oregon Kathleen Gemberling Adkison September 26 – November 20, 2004 Doris Chase Museum of Northwest Art, La Conner, Washington January 15 – April 3, 2005 Sally Haley Mary Henry Maude Kerns LaVerne Krause Hilda Morris Eunice Parsons Viola Patterson Ruth Penington Amanda Snyder Margaret Tomkins Eunice Parsons Mourning Flower 1969, collage, 26 x 13.5 Collection of the Artist Photo: Robert DiFranco Northwest Matriarchs of Modernism: Twelve Proto-feminists from Oregon and Washington Copyright 2004 Marylhurst University Post Offi ce Box 261 17600 Pacifi c Highway Marylhurst, Oregon 97036 503.636.8141 www.marylhurst.edu Artworks copyrighted to the artists. Essays copyrighted to writers Lois Allan and Matthew Kangas. 2 All rights reserved. ISBN 0-914435-44-2 Design: Fancypants Design Preface Northwest Matriarchs of Modernism: Twelve presented work created prior to 1970. Most of our Proto-feminists from Oregon and Washington exhibitions either present art created specifi cally grew out of a conversation with author and for The Art Gym, or are mid-career or retrospective critic Lois Allan. As women, we share a strong surveys of artists in the thick of their careers. -

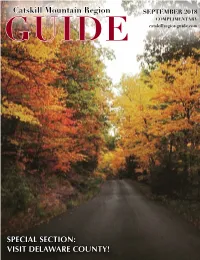

SEPTEMBER 2018 COMPLIMENTARY GUIDE Catskillregionguide.Com

Catskill Mountain Region SEPTEMBER 2018 COMPLIMENTARY GUIDE catskillregionguide.com SPECIAL SECTION: VISIT DELAWARE COUNTY! September 2018 • GUIDE 1 2 • www.catskillregionguide.com CONTENTS OF TABLE www.catskillregionguide.com VOLUME 33, NUMBER 9 September 2018 PUBLISHERS Peter Finn, Chairman, Catskill Mountain Foundation Sarah Finn, President, Catskill Mountain Foundation EDITORIAL DIRECTOR, CATSKILL MOUNTAIN FOUNDATION Sarah Taft ADVERTISING SALES Barbara Cobb Steve Friedman CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Heather Rolland, Jeff Senterman & Robert Tomlinson ADMINISTRATION & FINANCE Candy McKee Justin McGowan & Isabel Cunha On the cover: Photo by Elizabeth Hall Dukin PRINTING Catskill Mountain Printing Services 4 WOODSTOCK-NEW PALTZ ART & CRAFTS FAIR DISTRIBUTION Catskill Mountain Foundation 6 MOUNTAIN TOP ARBORETUM: Labor Day Events and New Timber Frame Education Center EDITORIAL DEADLINE FOR NEXT ISSUE: September 10 The Catskill Mountain Region Guide is published 12 times a year 10 WATERSHED AGRICULTURAL COUNCIL: Celebrating 25 by the Catskill Mountain Foundation, Inc., Main Street, PO Box 924, Hunter, NY 12442. If you have events or programs that you Years of Supporting the Region’s Farm and Forest Owners would like to have covered, please send them by e-mail to tafts@ catskillmtn.org. Please be sure to furnish a contact name and in- clude your address, telephone, fax, and e-mail information on all VISIT DELAWARE COUNTY: correspondence. For editorial and photo submission guidelines 12 send a request via e-mail to [email protected]. The Heart of the Great Western Catskills The liability of the publisher for any error for which it may be held legally responsible will not exceed the cost of space ordered or occupied by the error. -

The Politics of Urban Cultural Policy Global

THE POLITICS OF URBAN CULTURAL POLICY GLOBAL PERSPECTIVES Carl Grodach and Daniel Silver 2012 CONTENTS List of Figures and Tables iv Contributors v Acknowledgements viii INTRODUCTION Urbanizing Cultural Policy 1 Carl Grodach and Daniel Silver Part I URBAN CULTURAL POLICY AS AN OBJECT OF GOVERNANCE 20 1. A Different Class: Politics and Culture in London 21 Kate Oakley 2. Chicago from the Political Machine to the Entertainment Machine 42 Terry Nichols Clark and Daniel Silver 3. Brecht in Bogotá: How Cultural Policy Transformed a Clientist Political Culture 66 Eleonora Pasotti 4. Notes of Discord: Urban Cultural Policy in the Confrontational City 86 Arie Romein and Jan Jacob Trip 5. Cultural Policy and the State of Urban Development in the Capital of South Korea 111 Jong Youl Lee and Chad Anderson Part II REWRITING THE CREATIVE CITY SCRIPT 130 6. Creativity and Urban Regeneration: The Role of La Tohu and the Cirque du Soleil in the Saint-Michel Neighborhood in Montreal 131 Deborah Leslie and Norma Rantisi 7. City Image and the Politics of Music Policy in the “Live Music Capital of the World” 156 Carl Grodach ii 8. “To Have and to Need”: Reorganizing Cultural Policy as Panacea for 176 Berlin’s Urban and Economic Woes Doreen Jakob 9. Urban Cultural Policy, City Size, and Proximity 195 Chris Gibson and Gordon Waitt Part III THE IMPLICATIONS OF URBAN CULTURAL POLICY AGENDAS FOR CREATIVE PRODUCTION 221 10. The New Cultural Economy and its Discontents: Governance Innovation and Policy Disjuncture in Vancouver 222 Tom Hutton and Catherine Murray 11. Creating Urban Spaces for Culture, Heritage, and the Arts in Singapore: Balancing Policy-Led Development and Organic Growth 245 Lily Kong 12. -

Northwest Fine Art & Antique Auction

Northwest Fine Art & Antique Auction August 27th, 2009 - 717 S 3rd St, Renton 14% Buyers Premium in Effect Auction Pick-up: Half Hour Following Auction or Friday, 08/28 & Tuesday, 09/01: Noon-5PM Lot Description 21 2 Boxes Loose Richard Lachman Cut Ink Drawings 1 Richard Kirsten "House of Many 22 3ea Richard Lachman Colored Ink Drawings Memories" Acrylic 22x16" 23 Box Richard Lachman Square Ink Drawings 2 Edna Crews "Snowcapped Forest" 24 4ea Richard Lachman Portrait Ink Drawings Watercolor 16x20.75" 25 Richard Lachman Large Sketchbook & 3 James Farr "Infinite Cycle of Renewal" Loose Ink Drawings 1973 Tempera 23.5x18.5" 26 Stack Richard Lachman Ink Drawings - 4 1997 S/N Abstract Etching Sketchbook Pages 5 Norman Lundin "Russian Landscape: 27 5x11' Oriental Rug Morning River" Charcoal/Pastel 26x37" 28 2 Carol Stabile Pastel Framed Paintings 6 K.C. McLaughlin "Exterior with 29 1969 Surrealist Mixed Media Painting Awnings" Dry Pigment 17x25" 34x30" - Signed Riote? 7 Edna Crews "Moonlit Meadow" 30 Signed F.W. Die? "Eye" Ink/Canvas 16x20" Watercolor 16.5x21.5" 31 Fred Marshall A.W.S. "Harbor - Puget 8 Edna Crews "Winter Meadow" Acrylic Sound" 1970 Watercolor 17x20.5" 31.5x23" 32 Fred Marshall Framed Watercolor 9 Richard Lachman "Cocktail Party" 1980 "Landscape with Deer" 16x21" Ink/Paper 16x22" 33 Flora Correa "Weeds Blowing" 1977 Collage 10 Richard Lachman "Dixy & Jaques" 24x12" Mixed Media 18x26" 34 Bonnie Anderson "Bucket of Lemons" Oil 11 Richard Lachman "Day Before Eden" 8x10" Mixed Media 18x26" 35 Bonnie Anderson "Lemon Drop Tree" Oil 12 Natalie McHenry Untitled – 38x14.25" "Marionettes" Watercolor 19x25" 36 Ray Hill Untitled - "Lake Scene" 1969 13 Edna Crews Untitled - "Mystic Bird" Watercolor 14x20" Oil/Board 40x30" 37 Signed S.