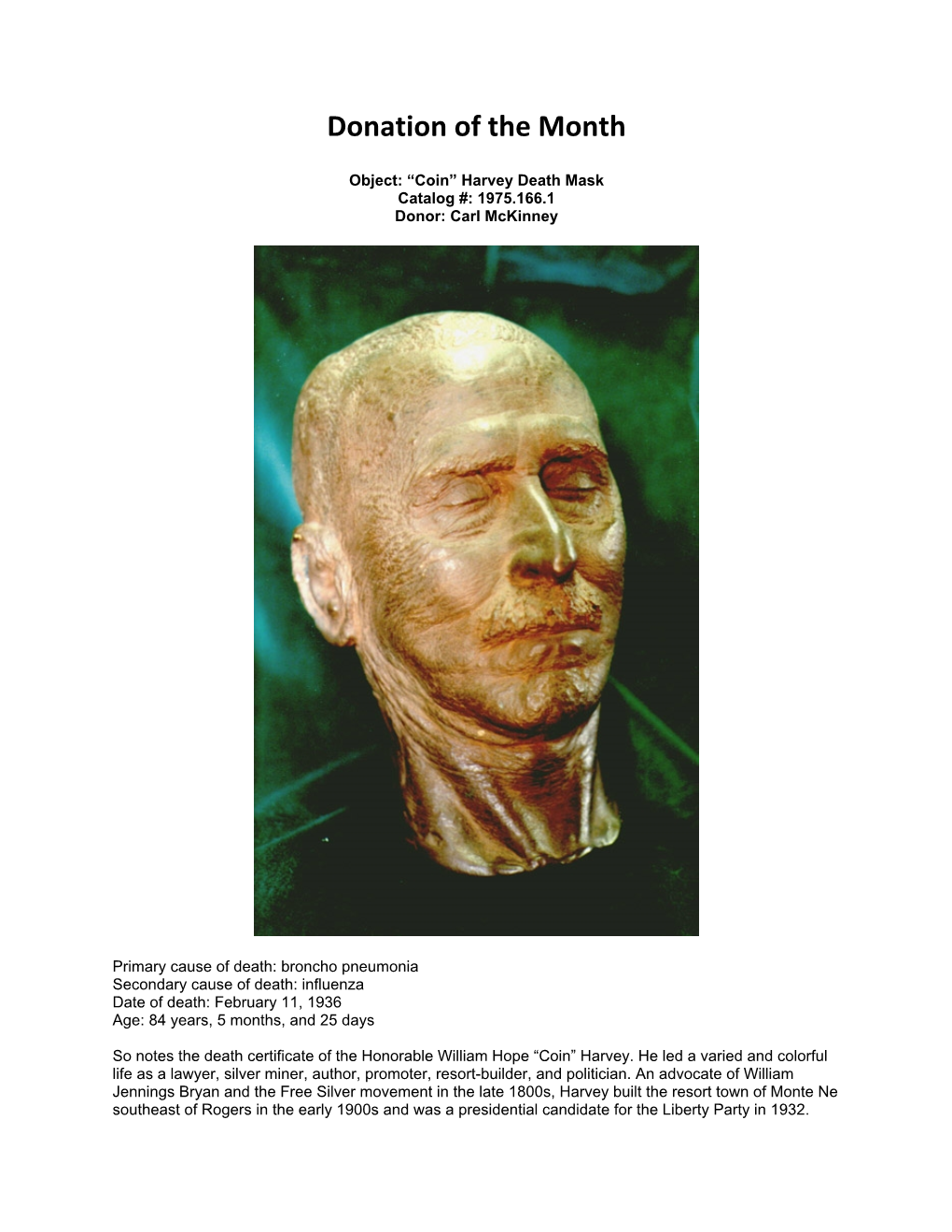

Coin Harvey's Death Mask

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grief and Cultural Competence: Hispanic, African American, & Jewish Traditions

Grief and Cultural Competence: Hispanic, African American, & Jewish Traditions 3 CE Hours Dr. Candi K. Cann, Ph.D. Funeral Service Academy PO Box 449 Pewaukee, WI 53072 www.funeralcourse.com [email protected] 888-909-5906 Course Instructions Each of the course PDFs below contain a preview of the final exam followed by the course material. The exam is identical to the final exam that you will take online after you purchase the course. You may use this exam preview to help you study the course material. After you purchase the course online, you will be taken to a receipt page which will have the following link: Click Here to Take Online Exam Simply click on this link to take the final exam and receive your certificate of completion. 3 Easy Steps to Complete a Course: 1. Read the course material below. 2. Purchase the course online & take the final exam. 3. Print out your certificate. If you don’t pass the exam, no problem – you can try it again for free! Funeral Service Academy PO Box 449 Pewaukee, WI 53072 [email protected] Final Exam - PREVIEW Course Name: Grief and Cultural Competence: Hispanic, African American, & Jewish Traditions (3 CE Hours) HISPANIC MODULE 1. Currently, Hispanics are the largest minority in the United States: ________ of the total United States population in the 2013 census. a. 38.7% b. 29.4% c. 21.6% d. 17.1% 2. The body of the deceased plays an active role in the Hispanic tradition, from the wake and rosary to the funeral mass and burial, and is a central “actor” in the religious rituals remembering the dead. -

ABSTRACTS of the International Congress on Wax Modelling Madrid, June 29Th-30Th, 2017 School of Medicine

JOURNAL INFORMATION Eur. J. Anat. 21 (3): 241-260 (2017) ABSTRACTS of the International Congress on Wax Modelling Madrid, June 29th-30th, 2017 School of Medicine. Complutense University Madrid, Spain 241 Abstracts HONORIFIC COMMITTEE Carlos Andradas, Chancellor of the Complutense University of Madrid María Nagore, Vice chancellor of Culture and Sports of the Complutense University of Madrid José Luis Álvarez-Sala, Dean of the Faculty of Medicine of the Complutense University of Madrid Elena Blanch, Dean of the Faculty of Fine Arts of the Complutense University of Madrid José Luis Gonzalo, Dean of the Faculty of Library and Information Science of the Complutense University of Madrid Pedro Luis Lorenzo, Dean of the Faculty of Veterinary of the Complutense University of Madrid SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Elena Blanch (Complutense University of Madrid) Raffaele de Caro (University of Padova) Isabel García (Complutense University of Madrid) Xabier Mas-Barberà (Polytechnic University of Valencia) Luis Montiel (Complutense University of Madrid) María Isabel Morente (Complutense University of Madrid) Javier Moscoso (Spanish National Research Council) Juan Francisco Pastor (University of Valladolid) Margarita San Andrés (Complutense University of Madrid) Alicia Sánchez (Complutense University of Madrid) Pedro Terrón (Complutense University of Madrid) Tomas Bañuelos (Complutense University of Madrid) Carmen Marcos (Polytechnic University of Valencia) ORGANISING COMMITTEE Presidents Elena Blanch (Complutense University of Madrid) Jose Ramón Sañudo (Complutense -

MOUND CITY GROUP National Monument • Ohio the by About 500 B.C

MOUND CITY GROUP National Monument • Ohio THE By about 500 B.C. the A "VI OTIT The Hopewell are best prehistoric Indians we now t s TT-^.T-vTy^i known for their high HOPEWELL call Hopewell had O 1 lA-IN D1IN Kj artistic achievements and developed a distinctive /o fMr c ce f PEOPLE culture in the Middle PREHISTORIC ; 7 " ° West. For perhaps 1,000 years these people flourished; erecting earth mounds their cultural zenith being here in the Scioto Valley of I IN DILVIN overdead the remainsFro of theirih ra southern Ohio. But by about A.D. 500 the Hopewell CULTURE , - :k :f -l culture had faded. Hundreds of years later European ordinary wealth or burial settlers found only deserted burial mounds and offerings found in the mounds, archeologists have learned ceremonial earthworks to hint at this vanished culture. a great deal about these prehistoric people. They were excellent artists and craftsmen and worked with a great variety of material foreign to Ohio. Copper from the Lake Superior region was used for earspools, headdresses, breastplates, ornaments, EFFIGY PIPE OF STONE ceremonial objects, and tools. Stone tobacco pipes were Since Mound City was WITH INLAID SHELL beautifully carved to represent the bird and animal MOUND CITY primarily a ceremonial life around them. From obsidian they made COPPER BREASTPLATE — 1800 center for the dead, delicately chipped ceremonial blades. Fresh-water much of the information pearls from local streams, quartz and mica from the YEARS obtained from it Blue Ridge Mountains, ocean shells from the 6 M und CH G produced a great many spectacular objects, most concerns the burial EXPLORATION^ ° \ T interesting of which were a large number of stone AGO Gulf of Mexico, grizzly bear teeth from the West—all es customs of the people. -

Images Re-Vues, 13 | 2016 the Deceptive Surface: Perception and Sculpture’S “Skin” 2

Images Re-vues Histoire, anthropologie et théorie de l'art 13 | 2016 Supports The Deceptive Surface: Perception and Sculpture’s “Skin” Illusion de surface : percevoir la « peau » d’une sculpture Christina Ferando Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/imagesrevues/3931 DOI: 10.4000/imagesrevues.3931 ISSN: 1778-3801 Publisher: Centre d’Histoire et Théorie des Arts, Groupe d’Anthropologie Historique de l’Occident Médiéval, Laboratoire d’Anthropologie Sociale, UMR 8210 Anthropologie et Histoire des Mondes Antiques Electronic reference Christina Ferando, “The Deceptive Surface: Perception and Sculpture’s “Skin””, Images Re-vues [Online], 13 | 2016, Online since 15 January 2017, connection on 30 January 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/imagesrevues/3931 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/imagesrevues.3931 This text was automatically generated on 30 January 2021. Images Re-vues est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d’Utilisation Commerciale 4.0 International. The Deceptive Surface: Perception and Sculpture’s “Skin” 1 The Deceptive Surface: Perception and Sculpture’s “Skin” Illusion de surface : percevoir la « peau » d’une sculpture Christina Ferando This paper was presented at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, as part of the symposium “Surfaces: Fifteenth – Nineteenth Centuries” on March 27, 2015. Many thanks to Noémie Étienne, organizer of the symposium, for inviting me to participate and reflect on the sculptural surface and to Laurent Vannini for the translation of this article into French. Images Re-vues, 13 | 2016 The Deceptive Surface: Perception and Sculpture’s “Skin” 2 1 Sculpture—an art of mass, volume, weight, and density. -

Funeral Directors As Servant-Leaders SHELBY CHISM and MICHAEL G

SERVING A DEATH-DENYING CULTURE Funeral Directors as Servant-Leaders SHELBY CHISM AND MICHAEL G. STRAWSER uneral directors have labeled the typical American society a death-denying culture. For example, parents may try to F shield children from the death event because of previous occurrences with death and the funeral home (Mahon, 2009). Unfortunately, by protecting others, the death-denying culture is perpetuated (Mahon, 2009). Therefore, it is no surprise that research on funeral directors, and funeral homes, may be underdeveloped. To address the scarcity of research literature on the impact of funeral directors, this article discusses the importance of the death care industry and provides an overview of servant-leadership theory as a framework for understanding the role of the 21st century funeral director. The funeral home industry has been studied through a servant-leadership framework (Long, 2009) yet, research on the funeral director as servant-leader is scarce. While it is true that funeral homes have been studied through a servant- leadership framework mostly through the lens of vocational effectiveness (Adnot-Haynes, 2013), relationships with the bereaved (Mahon, 2009), and trending professional 229 developments (Granquist, 2014), research on the role of the funeral director as a servant-leader remains underdeveloped. Funeral directors, an often ignored population in leadership and communication study, may display tendencies of servant- leadership and, potentially, communicate with clients primarily as servant-leaders. Despite a clear connection between funeral directing as a servant profession, and the necessity for servant-leaders to communicate compassionately and effectively with the bereaved, this vocation remains under- examined. Therefore, this article addresses the servanthood nature of leadership as demonstrated by funeral directors. -

Funeral Directors Association

JULY/AUGUST 2013 Minnesota FUNERAL DIRECTORS ASSOCIATION BULLETIN PUBLISHED MONTHLY FOR THE MINNESOTA FUNERAL DIRECTORS ASSOCIATION MEMBERS. Minnesota Funeral Directors Association Encourages Families to Have the Talk of a Lifetime Minneapolis, MN – People talk about many things with their loved ones: from day-to-day details to big events. Sharing stories with those who matter most isn’t just important today; it will be especially significant when it’s time to commemorate a life. Minnesota Funeral Directors Association (MFDA) is proud to announce its participation in Have the Talk of a LifetimeSM, a national effort to encourage families to have conversations about life and what matters most. These discussions can help families make important decisions about how they wish to remember and honor the lives of their loved ones. Through meaningful memorialization – that is, taking time to reflect on the unique life of a loved one and remember the difference they made – families and friends take an important step in the journey toward healing after death. Continued on page 6 SRSASSOCIAAVE THE DATE! TI ON DIRECTO MIN NESO NERAL Sept. 19-20, 2013 FU TA Change Service Requested Service Change TA NESO InsuranceMIN Class O. 23 O. N IT M PER Maple Grove, MN 55311 55311 MN Grove, Maple N PRIOR LAKE, M LAKE, PRIOR Embassy Suites, Brooklyn Center, MN Road Lake Fish East 7046 PAID POSTAGE . S U. Minnesota Funeral Directors Association Directors Funeral Minnesota RSASSOCIA TANDARD TANDARD S MFDA Bulletin MFDA PRESORTED PRESORTED TI ON DIRECTO MIN NESO NERAL FU TA Minnesota Funeral Director’s Association In This Issue Have the Talk of a Lifetime .............Cover, 6 Board of DirECTors, STaff and OTHER ConTacTS From the Director ..................................... -

Wax Flesh, Vicious Circles by Georges Didi-Huberman

Wax Flesh, Vicious Circles By Georges Didi-Huberman Wax Flesh Wax is the material of all resemblances. Its figurative virtues are so remarkable that it was often considered a prodigious, magical material, almost alive – and disquieting for that very reason. Even if we leave aside Pharaonic Egypt and its spellbinding texts, Pliny the Elder’s Natural History already catalogues, in the Roman Period, the entire technical-mythical repertory of medical, cosmetic, industrial, and religious properties of wax. Closer to our time, a Sicilian wax-worker, a modest supplier of exvotos and crèche figurines, expressed some fifteen years ago his wonder at the strange powers of this material, nonetheless so familiar to him: “It is marvelous. You can do anything with it […]. It moves.” (R. Credini, 1991) Yes, wax “moves.” To say that it is a plastic material is above all to say that it gives way almost without any resistance before any technique, before any formative process that one would impose on it. It goes exactly where you ask: it can be cut like butter with the sculptor’s chisel, or warmed up and easily modeled with the fingers; it flows effortlessly into molds whose volume and texture it adopts with astounding precision. Wax also “moves” in the sense that it permits the inscription, the duplication, the temporal as well as spatial displacement of the forms, which impress themselves into it, transforming, effacing and reforming themselves infinitely. Which is why, from Aristotle to Freud, this material has provided the privileged metaphor of the work of memory, and even of sensorial operations in general. -

Getty Publications Fall 2008 Getty Getty Fallpublications 2008 New Publications Titles

Getty Publications With Complete Backlist Fall 2008 Getty Getty Cover: Maria Sibylla Merian, lemon (Citrus medica) and harlequin beetle (Acrocinus longimanus) (Plate 28 in Maria Sibylla Merian's Insectorum Surinamensium). From Insects and Flowers, featured on page 6. Publications Publications New New Titles Titles New Titles Bernini and the Birth of Baroque Portrait Sculpture Edited by Andrea Bacchi, Catherine Hess, and Jennifer Montagu, with the assistance of Anne-Lise Desmas Gian Lorenzo Bernini was the greatest sculptor of the Baroque period, and yet — surprisingly — there has never been a major North American exhibition of his work. Bernini and the Birth of Baroque Portrait Sculpture — on view from August 5 through October 26, 2008, at the J. Paul Getty Museum and from November 28, 2008, Contents through March 8, 2009, at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa — showcases portrait sculptures from all phases of the artist’s long career, from the very early Antonio Coppola of 1612 to Clement X of about 1676. FRON TLIST 1 Bernini’s portrait busts were masterpieces of technical virtuosity; at the same time, they revealed a new interest in psychological depth. Bernini’s ability to capture the essential character of his subjects was Bernini and the Birth of Baroque Portrait Sculpture 1 unmatched and had a profound influence on other leading sculptors of his day, such as Alessandro Algardi, Captured Emotions 2 Giuliano Finelli, and Francesco Mochi. The Art of Mantua 3 Bernini and the Birth of Baroque Portrait Sculpture is a groundbreaking study that also features drawings and paintings by Bernini and his contemporaries. -

Chapter: Religion and the Funeral Director

Chapter: Religion and the Funeral Director 2 CE Hours By: Elite Staff Learning objectives Be able to conduct each funeral service with dignity and respect, In dealing with the bereaved, be able to: adapting funeral arrangements to serve the needs of each family as ○ Understand and respect the values of the people you serve. appropriate and according to their means, customs, and religious, ○ Provide interpreters, if necessary. cultural and national traditions. ○ Reduce incidents of perceived discrimination, lack of empathy, Be able to recognize, understand and adapt to the needs of ethnic or hostility due to ignorance of specific customs and traditions. communities as well as mainstream or numerically dominant Be accountable and able to serve the multicultural consumer base. groups. Demographic trends in the United States1 Demographic trends in North America point to increasing diversity century is seeing the development of three major subcultures: African of religion, nation of origin, culture and subculture. In the United American, Hispanic, and Asian American. Within each of these groups States, the racial and ethnic composition of the country is changing are subgroups defined by different languages, cultures and religions. – no longer a white majority and black minority, the early part of this Variation within groups Funeral rites vary not only by religion and culture, but also by country While each ritual is unique, most funerals include the following of origin, family customs, financial resources and/or the personal components: 2 preferences of the individual and families involved in the ritual. This ● A death announcement. course introduces customs and cultures characteristic of some of the ● Some preparation of the deceased. -

The Death-Mask and Other Ghosts

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE Cornell University Library f>R 4699.E842D2 The death-mask and other ghosts. 3 1924 013 456 953 Cornell University Library The original of tliis bool< is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924013456953 THE DEATH-MASK THE DEATH-MASK AND OTHER GHOSTS BY Mrs. H. D. EVERETT. LONDON , ii^ PHILIP ALLAN ^ CO., QUALITY COURT, CHANCE^iY , LAWe!, W.C. 1920. PRINTED BY WHITBHHAD BROS., WOLVERHAMPTON. r-:''- ... CONTENTS. PACB The Death- Mask - ] Parson Clench 18 The Wind of Dunowe .17 Nevill Nugent's Legacy • 67 The Crimson Blind 92 Fingers of a Hand 115 The Next Heir - - - 128 Anne's Little Ghost - 188 Over the Wires - - 208 A Water-Witch - 223 The Lonely Road 253 A Girl in White 261 A Perplexing Case - 279 Beyond the Pale 298 THE DEATH MASK. ' ' Yes, that is a portrait of my wife. It is considered to be a good likeness. But of course she was older-looking towards the last." ' Enderby and I were on our way to the smoking-room after dinner, and the picture hung on the staircase. We had been chums at school a quarter of a century ago, and later on at college; but I had spent the last decade out of England. I returned to find my friend a widower of four years' standing. And a good job too, I thought to myself when I heard of it, for I had no great liking for the late Gloriana. -

THE DEATH-MASKS of DEAN SWIFT by T

THE DEATH-MASKS OF DEAN SWIFT bY T. G. WILSON THE practice of making death-masks is of considerable antiquity, dating at least from the fifteenth century. Originally it had two purposes. One was to form the head of an effigy used in the funeral ceremonies of kings, queens, princes and other distinguished persons. A life-sized wooden effigy was made which was clothed and carried on the coffin in the funeral procession, the head and hands being covered with life-like wax modelling. This was used as a substitute for the body at funeral ceremonies which might take place long after the latter had been buried. Many of these effigies are still to be seen in West- minster Abbey. Two copies of the death-mask of Oliver Cromwell are extant, one in wax and one in plaster of paris. He died on 3 September I658, and his remains were quietly buried three weeks later. Nevertheless a wax effigy in full panoply ofstate was exhibited for several months afterwards in Somerset House while the state funeral did not take place until 22 October.John Evelyn tells us: He was carried from Somerset House in a velvet bed ofstate, drawn by six horses, housed in the same; the pall held by his new Lords; Oliver lying in effigy, in royal robes, and crowned with a crown, sceptre, and globe, like a king. The pendants and guidons were carried by the officers of the army; the Imperial banners, achievements, &c. by the heralds in their coats; a rich caparisoned horse, embroidered all over with gold; a knight of honour, armed cap-a-pii. -

Face and Mask

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. For us the most entertaining surface in the world Is that of the human face. Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, Sudelbücher, F. 88 introDUction: Defining tHe sUbject 1 A history of the face? It is an audacious undertaking to tackle a subject that defies all categories and leads to the quintessential image with which all humans live. For what, actually, is “the face”? While it is the face that each of us has, it is also just one face among many. But it does not truly become a face until it interacts with other faces, seeing or being seen by them. This is evident in the expression “face to face,” which designates the immediate, perhaps inescapable, interaction of a reciprocal glance in a moment of truth between two human beings. But a face comes to life in the most literal sense only through gaze and voice, and so it is with the play of human facial expressions. To exaggerate a facial expression is to “make a face” in order to convey a feeling or address someone without using words. To put it differ- ently, it is to portray oneself using one’s own face while observing conventions that help us understand each other. Language provides many ready examples of figures of speech that derive from facial animation. The metaphors we all automatically use about facial expressions are particularly revealing. “To save face” or “to lose face” are typical of these.