State Plans for Accelerating Student Learning: a Preliminary Analysis April 21, 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Approved Student Calendar

2007-2008 Student Calendar July 2007 August 2007 September 2007 SMTWT F S SMTWT F S SMTWT F S 1234567 1234 1 8910111213145678910 11 2 3 45678 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 29 30 31 26 27 28 29 30 31 30 24 25 26 27 28 29 October 2007 November 2007 December 2007 SMTWT F S SMTWT F S SMTWT F S 123456 123 1 7891011 12 134567 89102345678 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 28 29 30 31 25 26 27 28 29 30 30 31 25 26 27 28 29 January 2008 February 2008 March 2008 SMTWT F S SMTWT F S SMTWT F S 12345 12 1 67891011123456789 2345678 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 10 11 12 13 14 1516 9 1011121314 15 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 27 28 29 30 31 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 25 26 27 28 29 April 2008 May 2008 June 2008 SMTWT F S SMTWT F S SMTWT F S 12345 123 1234567 6789 10111245678910891011121314 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 27 28 29 30 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 29 30 Regular School Day Schools Closed Early Dismissal Parent Conference Report Card Distribution * This calendar was adjusted to accommodate the spring NASCAR race. -

Pricing*, Pool and Payment** Due Dates January - December 2021 Mideast Marketing Area Federal Order No

Pricing*, Pool and Payment** Due Dates January - December 2021 Mideast Marketing Area Federal Order No. 33 Class & Market Administrator Payment Dates for Producer Milk Component Final Pool Producer Advance Prices Payment Dates Final Payment Due Partial Payment Due Pool Month Prices Release Date Payrolls Due & Pricing Factors PSF, Admin., MS Cooperative Nonmember Cooperative Nonmember January February 3 * February 13 February 22 December 23, 2020 February 16 ** February 16 February 17 Janaury 25 January 26 February March 3 * March 13 March 22 January 21 * March 15 March 16 March 17 February 25 February 26 March March 31 * April 13 April 22 February 18 * April 15 April 16 April 19 ** March 25 March 26 April May 5 May 13 May 22 March 17 * May 17 ** May 17 ** May 17 April 26 ** April 26 May June 3 * June 13 June 22 April 21 * June 15 June 16 June 17 May 25 May 26 June June 30 * July 13 July 22 May 19 * July 15 July 16 July 19 ** June 25 June 28 ** July August 4 * August 13 August 22 June 23 August 16 ** August 16 August 17 July 26 ** July 26 August September 1 * September 13 September 22 July 21 * September 15 September 16 September 17 August 25 August 26 September September 29 * October 13 October 22 August 18 * October 15 October 18 ** October 18 ** September 27 ** September 27 ** October November 3 * November 13 November 22 September 22 * November 15 November 16 November 17 October 25 October 26 November December 1 * December 13 December 22 October 20 * December 15 December 16 December 17 November 26 ** November 26 December January 5, 2022 January 13, 2022 January 22, 2022 November 17 * January 18, 2022 ** January 18, 2022 ** January 18, 2022 ** December 27 ** December 27 ** * If the release date does not fall on the 5th (Class & Component Prices) or 23rd (Advance Prices & Pricing Factors), the most current release preceding will be used in the price calculation. -

2021 Calandar

Harbortown Point Marina Resort & Club 2021 Reservation Calendar Written request can be taken at dates indicated Please note: you can only book in Prime season if you own in Prime Season and only below. The dates inform book in High Season if you own in High Season you when the 2021 weeks to the left Friday Saturday Sunday become abailable to Week No. Dates Dates Dates reserve. 1 Jan 1 - Jan 8 Jan 2 - Jan 9 Jan 3 - Jan 10 October 22, 2019 2 Jan 8 - Jan 15 Jan 9 - Jan 16 Jan 10 - Jan 17 October 29, 2019 3 Jan 15 - Jan 22 Jan 16 - Jan 23 Jan 17 - Jan 24 November 5, 2019 4 Jan 22 - Jan 29 Jan 23 - Jan 30 Jan 24 - Jan 31 November 12, 2019 5 Jan 29 - Feb 5 Jan 30 - Feb 6 Jan 31 - Feb 7 November 19, 2019 6 Feb 5 - Feb 12 Feb 6- Feb 13 Feb 7 - Feb 14 November 26, 2019 7 Feb 12 - Feb 19 Feb 13 - Feb 20 Feb 14 - Feb 21 December 3, 2019 8 Feb 19 - Feb 26 Feb 20 - Feb 27 Feb 21 - Feb 28 December 10, 2019 9 Feb 26 - Mar 5 Feb 27 - Mar 6 Feb 28 - Mar 7 December 18, 2018 HIGH 10 Mar 5 - Mar 12 Mar 6 - Mar 13 Mar 7 - Mar 14 December 17, 2019 11 Mar 12 - Mar 19 Mar 13 - Mar 20 Mar 14 - Mar21 December 24, 2019 12 Mar 19 - Mar 26 Mar 20 - Mar 27 Mar 21 - Mar 28 December 31, 2019 13 Mar 26 - Apr 2 Mar 27 - Apr 3 Mar 28 - Apr 4 January 7, 2020 14 April 2 - April 9 April 3 - April 10 April 4 - April 11 January 14, 2020 15 April 9 - April 16 Apr 10 - Apr 17 Apr 11 - Apr 18 January 21, 2020 16 April 16 - April 23 Apr 17 - Apr 24 Apr 18 - Apr 25 January 28, 2020 17 April 23 - April 30 Apr 24 - May 1 Apr 25 - May 2 February 4, 2020 18 Apr 30 - May 7 May 1 - May -

2021-2022 Custom & Standard Information Due Dates

2021-2022 CUSTOM & STANDARD INFORMATION DUE DATES Desired Cover All Desired Cover All Delivery Date Info. Due Text Due Delivery Date Info. Due Text Due May 31 No Deliveries No Deliveries July 19 April 12 May 10 June 1 February 23 March 23 July 20 April 13 May 11 June 2 February 24 March 24 July 21 April 14 May 12 June 3 February 25 March 25 July 22 April 15 May 13 June 4 February 26 March 26 July 23 April 16 May 14 June 7 March 1 March 29 July 26 April 19 May 17 June 8 March 2 March 30 July 27 April 20 May 18 June 9 March 3 March 31 July 28 April 21 May 19 June 10 March 4 April 1 July 29 April 22 May 20 June 11 March 5 April 2 July 30 April 23 May 21 June 14 March 8 April 5 August 2 April 26 May 24 June 15 March 9 April 6 August 3 April 27 May 25 June 16 March 10 April 7 August 4 April 28 May 26 June 17 March 11 April 8 August 5 April 29 May 27 June 18 March 12 April 9 August 6 April 30 May 28 June 21 March 15 April 12 August 9 May 3 May 28 June 22 March 16 April 13 August 10 May 4 June 1 June 23 March 17 April 14 August 11 May 5 June 2 June 24 March 18 April 15 August 12 May 6 June 3 June 25 March 19 April 16 August 13 May 7 June 4 June 28 March 22 April 19 August 16 May 10 June 7 June 29 March 23 April 20 August 17 May 11 June 8 June 30 March 24 April 21 August 18 May 12 June 9 July 1 March 25 April 22 August 19 May 13 June 10 July 2 March 26 April 23 August 20 May 14 June 11 July 5 March 29 April 26 August 23 May 17 June 14 July 6 March 30 April 27 August 24 May 18 June 15 July 7 March 31 April 28 August 25 May 19 June 16 July 8 April 1 April 29 August 26 May 20 June 17 July 9 April 2 April 30 August 27 May 21 June 18 July 12 April 5 May 3 August 30 May 24 June 21 July 13 April 6 May 4 August 31 May 25 June 22 July 14 April 7 May 5 September 1 May 26 June 23 July 15 April 8 May 6 September 2 May 27 June 24 July 16 April 9 May 7 September 3 May 28 June 25. -

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar The Working Day Calendar is used to compute the estimated completion date of a contract. To use the calendar, find the start date of the contract, add the working days to the number of the calendar date (a number from 1 to 1000), and subtract 1, find that calculated number in the calendar and that will be the completion date of the contract Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, January 1, 2021 133 Saturday, January 2, 2021 134 Sunday, January 3, 2021 135 Monday, January 4, 2021 136 Tuesday, January 5, 2021 137 Wednesday, January 6, 2021 138 Thursday, January 7, 2021 139 Friday, January 8, 2021 140 Saturday, January 9, 2021 141 Sunday, January 10, 2021 142 Monday, January 11, 2021 143 Tuesday, January 12, 2021 144 Wednesday, January 13, 2021 145 Thursday, January 14, 2021 146 Friday, January 15, 2021 147 Saturday, January 16, 2021 148 Sunday, January 17, 2021 149 Monday, January 18, 2021 150 Tuesday, January 19, 2021 151 Wednesday, January 20, 2021 152 Thursday, January 21, 2021 153 Friday, January 22, 2021 154 Saturday, January 23, 2021 155 Sunday, January 24, 2021 156 Monday, January 25, 2021 157 Tuesday, January 26, 2021 158 Wednesday, January 27, 2021 159 Thursday, January 28, 2021 160 Friday, January 29, 2021 161 Saturday, January 30, 2021 162 Sunday, January 31, 2021 163 Monday, February 1, 2021 164 Tuesday, February 2, 2021 165 Wednesday, February 3, 2021 166 Thursday, February 4, 2021 167 Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, February 5, 2021 168 Saturday, February 6, 2021 169 Sunday, February -

A Nation Empowered: Evidence Trumps the Excuses Holding Back America’S Brightest Students

Evidence Trumps the Excuses Holding Back America’s Brightest Students VOLUME 1 Susan G. Assouline, Nicholas Colangelo, and Joyce VanTassel-Baska Mary Sharp, Writing Consultant Belin-Blank Center, College of Education, University of Iowa Evidence Trumps the Excuses Holding Back America’s Brightest Students VOLUME 1 Susan G. Assouline, Nicholas Colangelo, and Joyce VanTassel-Baska Mary Sharp, Writing Consultant The Connie Belin & Jacqueline N. Blank International Center for Gifted Education and Talent Development College of Education University of Iowa Dedicated to the memory of: Julian C. Stanley, Johns Hopkins University, founder of the Talent Search Model and the Study of Mathematically Precocious Youth and James J. Gallagher, University of North CarolinaChapel Hill, pioneer in educational policy related to special and gifted education Their scholarship and advocacy for the intervention of acceleration positively impacts the lives of tens of thousands of students and their families and educators. ©2015 The Connie Belin & Jacqueline N. Blank International Center for Gifted Education and Talent Development Endorsed by the National Association for Gifted Children, 1331 H Street, NW, Suite 1001, Washington, DC 20005 ISBN: 978-0-9961603-1-5 Designed by Benson and Hepker Design, Iowa City, Iowa Cover art by Robyn Hepker Published by The Belin-Blank Center, Iowa City, Iowa Printed at Colorweb Printing, Cedar Rapids, Iowa April 2015 The Connie Belin & Jacqueline N. Blank International Center for Gifted Education and Talent Development College of Education University of Iowa 600 Blank Honors Center Iowa City, Iowa 52242-0454 800.336.6463 www.education.uiowa.edu/belinblank www.accelerationinstitute.org www.nationdeceived.org www.nationempowered.org A Nation Empowered Evidence Trumps the Excuses Holding Back America’s Brightest Students Volume 1 Acknowledgements. -

Admission to Australian Universities for Accelerated Students

Admission to Australian Universities for Accelerated Students: Issues of Access, Attitude and Adjustment. Marie Young Bachelor of Arts (Monash University), Diploma of Education (Monash University), Master of Education (University of New South Wales). A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, School of Education, University of New South Wales. 2010 2 Publications The following article is based on Phase 1 of the thesis: Young, M., Rogers, K. B., & Ayres, P. (2007). The state of early tertiary admission in Australia: 2000 to present. Australasian Journal of Gifted Education, 16 (2), 15-25. The following article is based on Phase 2 of the thesis: Young, M., Rogers, K. B., & Ayres, P. (2009). Getting in: Australian university decision-making processes when gifted learners apply for early admission. Australasian Journal of Gifted Education, 18(2), 43-54. 3 Abstract University admission is a significant issue for gifted students who have been accelerated. This study explored access to Australian universities for accelerated students, examined the attitude of Australian universities to admission of accelerated students, and investigated issues of accelerated students’ adjustment to university. There is little research in Australia on these issues. In Phase 1 of the study, information about early admission, dual enrolment, minimum admission age, and admission of students younger than 17 years to Australian universities was collected and summarised. In Phase 2 personnel from 11 Australian universities were interviewed about the decision- making process which allowed such students to gain admission earlier than usual. Issues of support, advertising and national coordination were also examined. Phase 3 focused on interviews with 12 accelerated students concerning their adjustment to university, and any hurdles they identified. -

April 21, 2021

Updated as of April 21, 2021 This page is updated the first and third Wednesday of every month with news and report release information. For a schedule of report releases, please see our Report Calendar. Released to the Public • The following Parent Dashboard metrics have been updated: o Postsecondary Completion Rate, Postsecondary Enrollment and Postsecondary Persistence have been updated with 2019-20 data. o Ratio of Students to Instructional Staff has been updated with 2020-21 data. Coming Soon • COVID-19 continues to affect how districts provide instruction to their students. The Extended COVID-19 Learning Plan Dashboard will be updated to include new data collected as of April 23. • The Postsecondary Enrollment Parent Dashboard metric will be updated with 2020-21 data. • For users with secure login access, the Postsecondary Student Data File shows student-level information on college enrollment, coursework, cumulative credit, program and award information, and GPAs for students from in-state and out-of-state colleges and universities. This report will be updated with 2019-20 postsecondary data for high school graduation years 2018-19 and prior. • Postsecondary data showing enrollment, credit accumulation, remedial coursework and degree attainment, along with select demographic breakdowns for each high school graduating class are packaged in the Postsecondary Trends by High School report. School year 2019-20 data will be added. • The Success Rates report will be updated with 2019-20 data. This report shows the number of degree-seeking students achieving successful outcomes at Michigan’s public universities and community colleges. Successes include Center for Educational Performance and Information earning a certificate, associate or bachelor’s degree at a public university or community college or transferring to a 4-year institution as a degree-seeking student from a community college. -

Flex Dates.Xlsx

1st Day 1st Day of Your Desired Stay you may Call January 3, 2021 ↔ November 4, 2020 January 4, 2021 ↔ November 5, 2020 January 5, 2021 ↔ November 6, 2020 January 6, 2021 ↔ November 7, 2020 January 7, 2021 ↔ November 8, 2020 January 8, 2021 ↔ November 9, 2020 January 9, 2021 ↔ November 10, 2020 January 10, 2021 ↔ November 11, 2020 January 11, 2021 ↔ November 12, 2020 January 12, 2021 ↔ November 13, 2020 January 13, 2021 ↔ November 14, 2020 January 14, 2021 ↔ November 15, 2020 January 15, 2021 ↔ November 16, 2020 January 16, 2021 ↔ November 17, 2020 January 17, 2021 ↔ November 18, 2020 January 18, 2021 ↔ November 19, 2020 January 19, 2021 ↔ November 20, 2020 January 20, 2021 ↔ November 21, 2020 January 21, 2021 ↔ November 22, 2020 January 22, 2021 ↔ November 23, 2020 January 23, 2021 ↔ November 24, 2020 January 24, 2021 ↔ November 25, 2020 January 25, 2021 ↔ November 26, 2020 January 26, 2021 ↔ November 27, 2020 January 27, 2021 ↔ November 28, 2020 January 28, 2021 ↔ November 29, 2020 January 29, 2021 ↔ November 30, 2020 January 30, 2021 ↔ December 1, 2020 January 31, 2021 ↔ December 2, 2020 February 1, 2021 ↔ December 3, 2020 February 2, 2021 ↔ December 4, 2020 1st Day 1st Day of Your Desired Stay you may Call February 3, 2021 ↔ December 5, 2020 February 4, 2021 ↔ December 6, 2020 February 5, 2021 ↔ December 7, 2020 February 6, 2021 ↔ December 8, 2020 February 7, 2021 ↔ December 9, 2020 February 8, 2021 ↔ December 10, 2020 February 9, 2021 ↔ December 11, 2020 February 10, 2021 ↔ December 12, 2020 February 11, 2021 ↔ December 13, 2020 -

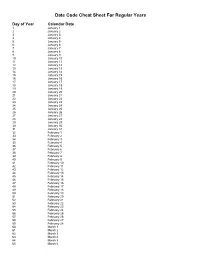

Julian Date Cheat Sheet for Regular Years

Date Code Cheat Sheet For Regular Years Day of Year Calendar Date 1 January 1 2 January 2 3 January 3 4 January 4 5 January 5 6 January 6 7 January 7 8 January 8 9 January 9 10 January 10 11 January 11 12 January 12 13 January 13 14 January 14 15 January 15 16 January 16 17 January 17 18 January 18 19 January 19 20 January 20 21 January 21 22 January 22 23 January 23 24 January 24 25 January 25 26 January 26 27 January 27 28 January 28 29 January 29 30 January 30 31 January 31 32 February 1 33 February 2 34 February 3 35 February 4 36 February 5 37 February 6 38 February 7 39 February 8 40 February 9 41 February 10 42 February 11 43 February 12 44 February 13 45 February 14 46 February 15 47 February 16 48 February 17 49 February 18 50 February 19 51 February 20 52 February 21 53 February 22 54 February 23 55 February 24 56 February 25 57 February 26 58 February 27 59 February 28 60 March 1 61 March 2 62 March 3 63 March 4 64 March 5 65 March 6 66 March 7 67 March 8 68 March 9 69 March 10 70 March 11 71 March 12 72 March 13 73 March 14 74 March 15 75 March 16 76 March 17 77 March 18 78 March 19 79 March 20 80 March 21 81 March 22 82 March 23 83 March 24 84 March 25 85 March 26 86 March 27 87 March 28 88 March 29 89 March 30 90 March 31 91 April 1 92 April 2 93 April 3 94 April 4 95 April 5 96 April 6 97 April 7 98 April 8 99 April 9 100 April 10 101 April 11 102 April 12 103 April 13 104 April 14 105 April 15 106 April 16 107 April 17 108 April 18 109 April 19 110 April 20 111 April 21 112 April 22 113 April 23 114 April 24 115 April -

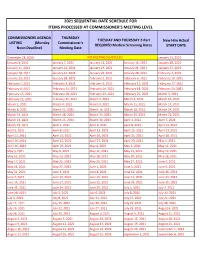

2021 Sequential Date List

2021 SEQUENTIAL DATE SCHEDULE FOR ITEMS PROCESSED AT COMMISSIONER'S MEETING LEVEL COMMISSIONERS AGENDA THURSDAY TUESDAY AND THURSDAY 2-Part New Hire Actual LISTING (Monday Commissioner's REQUIRED Medical Screening Dates START DATE Noon Deadline) Meeting Date December 28, 2020 NO MEETING SCHEDULED January 13, 2021 January 4, 2021 January 7, 2021 January 12, 2021 January 14, 2021 January 20, 2021 January 11, 2021 January 14, 2021 January 19, 2021 January 21, 2021 January 27, 2021 January 18, 2021 January 21, 2021 January 26, 2021 January 28, 2021 February 3, 2021 January 25, 2021 January 28, 2021 February 2, 2021 February 4, 2021 February 10, 2021 February 1, 2021 February 4, 2021 February 9, 2021 February 11, 2021 February 17, 2021 February 8, 2021 February 11, 2021 February 16, 2021 February 18, 2021 February 24, 2021 February 15, 2021 February 18, 2021 February 23, 2021 February 25, 2021 March 3, 2021 February 22, 2021 February 25, 2021 March 2, 2021 March 4, 2021 March 10, 2021 March 1, 2021 March 4, 2021 March 9, 2021 March 11, 2021 March 17, 2021 March 8, 2021 March 11, 2021 March 16, 2021 March 18, 2021 March 24, 2021 March 15, 2021 March 18, 2021 March 23, 2021 March 25, 2021 March 31, 2021 March 22, 2021 March 25, 2021 March 30, 2021 April 1, 2021 April 7, 2021 March 29, 2021 April 1, 2021 April 6, 2021 April 8, 2021 April 14, 2021 April 5, 2021 April 8, 2021 April 13, 2021 April 15, 2021 April 21, 2021 April 12, 2021 April 15, 2021 April 20, 2021 April 22, 2021 April 28, 2021 April 19, 2021 April 22, 2021 April 27, 2021 April -

A Nation Deceived: How Schools Hold Back America’S Brightest Students a Nation Deceived

A Nation Deceived: How Schools Hold Back America’s Brightest Students A Nation Deceived The Templeton National Report on Acceleration What Parents, Teachers and Other Professionals Nicholas Colangelo Should Know Susan G. Assouline Miraca U. M. Gross About the October 2004 Templeton National Report on Acceleration The Connie Belin & Jacqueline N. Blank International Center for Gifted Education and Talent Development College of Education, The University of Iowa 600 Blank Honors Center Iowa City, Iowa 52242-0454 November 26, 2005 800.336.6463 http://www.nationdeceived.org Presenters Background • Debbi Andrews, MD • Debra Arnison Sutton • summit on acceleration at University of Iowa in • parent • parent May 2003 formulate national report on acceleration • Developmental • AABC/EABC member pediatrician, U of Alberta • involved in developing • what schools need to know in order to make the • involved in multi- Alberta Education's “The best decisions about educating highly capable disciplinary Journey: A Handbook for students developmental Parents of Children Who assessment of children Are Gifted and Talented” • A Nation Deceived: How Schools Hold Back with special needs, America’s Brightest Students including gifted 3 4 Background Background •alarm to schools on the need to provide • tackles current misconceptions about acceleration accelerative experiences for brightest students and dispels their impact through •solid research base over last 50 years – research continuously demonstrates positive impacts of – examples of effective practice