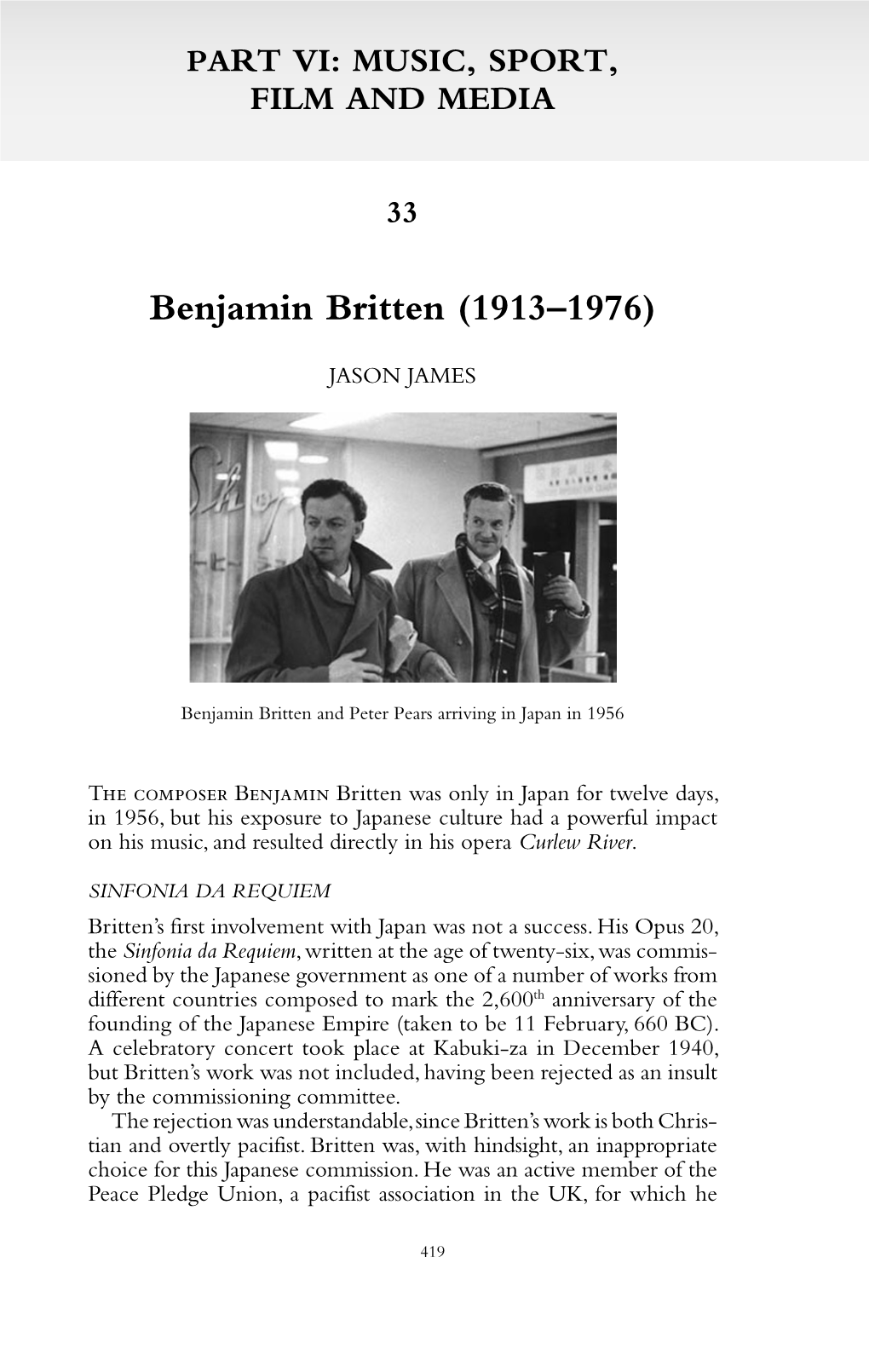

Benjamin Britten (1913–1976)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For All the Attention Paid to the Striking Passage of Thirty-Four

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Humanities Commons for Jane, on our thirty-fourth Accents of Remorse The good has never been perfect. There is always some flaw in it, some defect. First Sightings For all the attention paid to the “interview” scene in Benjamin Britten’s opera Billy Budd, its musical depths have proved remarkably resistant to analysis and have remained unplumbed. This striking passage of thirty-four whole-note chords has probably attracted more comment than any other in the opera since Andrew Porter first spotted shortly after the 1951 premiere that all the chords harmonize members of the F major triad, leading to much discussion over whether or not the passage is “in F major.” 1 Beyond Porter’s perception, the structure was far from obvious, perhaps in some way unprecedented, and has remained mysterious. Indeed, it is the undisputed gnomic power of its strangeness that attracted (and still attracts) most comment. Arnold Whittall has shown that no functional harmonic or contrapuntal explanation of the passage is satisfactory, and proceeded from there to make the interesting assertion that that was the point: The “creative indecision”2 that characterizes the music of the opera was meant to confront the listener with the same sort of difficulty as the layers of irony in Herman Melville’s “inside narrative,” on which the opera is based. To quote a single sentence of the original story that itself contains several layers of ironic ambiguity, a sentence thought by some—I believe mistakenly—to say that Vere felt no remorse: 1. -

Benjamin Britten: a Catalogue of the Orchestral Music

BENJAMIN BRITTEN: A CATALOGUE OF THE ORCHESTRAL MUSIC 1928: “Quatre Chansons Francaises” for soprano and orchestra: 13 minutes 1930: Two Portraits for string orchestra: 15 minutes 1931: Two Psalms for chorus and orchestra Ballet “Plymouth Town” for small orchestra: 27 minutes 1932: Sinfonietta, op.1: 14 minutes Double Concerto in B minor for Violin, Viola and Orchestra: 21 minutes (unfinished) 1934: “Simple Symphony” for strings, op.4: 14 minutes 1936: “Our Hunting Fathers” for soprano or tenor and orchestra, op. 8: 29 minutes “Soirees musicales” for orchestra, op.9: 11 minutes 1937: Variations on a theme of Frank Bridge for string orchestra, op. 10: 27 minutes “Mont Juic” for orchestra, op.12: 11 minutes (with Sir Lennox Berkeley) “The Company of Heaven” for two speakers, soprano, tenor, chorus, timpani, organ and string orchestra: 49 minutes 1938/45: Piano Concerto in D major, op. 13: 34 minutes 1939: “Ballad of Heroes” for soprano or tenor, chorus and orchestra, op.14: 17 minutes 1939/58: Violin Concerto, op. 15: 34 minutes 1939: “Young Apollo” for Piano and strings, op. 16: 7 minutes (withdrawn) “Les Illuminations” for soprano or tenor and strings, op.18: 22 minutes 1939-40: Overture “Canadian Carnival”, op.19: 14 minutes 1940: “Sinfonia da Requiem”, op.20: 21 minutes 1940/54: Diversions for Piano(Left Hand) and orchestra, op.21: 23 minutes 1941: “Matinees musicales” for orchestra, op. 24: 13 minutes “Scottish Ballad” for Two Pianos and Orchestra, op. 26: 15 minutes “An American Overture”, op. 27: 10 minutes 1943: Prelude and Fugue for eighteen solo strings, op. 29: 8 minutes Serenade for tenor, horn and strings, op. -

Adjustment and Debt

9832 Public Disclosure Authorized The World Bank Research Program 1990 Public Disclosure Authorized Abstracts of Public Disclosure Authorized Current Studies Public Disclosure Authorized THE WORLD BANK RESEARCH PROGRAM 1990 ABSTRACTS OF CURRENT STUDIES The World Bank Washington, D.C. Copyright @ 1991 by the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/Ihe World Bank 1818 H Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20433, U.S.A. All rights reserved. First printing: July 1991 Manufactured in the United States of America ISSN 0258-3143 ISBN 0-8213-1885-3 RESEARCH AT THE WORLD BANK The term "research," in its broadest definition, en- Policy Council (RPPC) chaired by the Senior Vice Presi- compasses a wide spectrum of Bank activities. Much dent, Policy, Research, and External Affairs, sets priority economic and sector work - analytical work to support guidelines for all Bank-supported research. RPPC mem- operations - generates new knowledge about member bers are drawn from the ranks of Bank senior managers, countries. Outside the Bank, this work might well be seen mainly vice presidents. as research. By convention, however, Bank research is Bank research is funded through two sources: de- defined more narrowly to include only analytical work partmental resources, mainly staff time, and the Research designed to produce results with relatively wide applica- Support Budget. The RSB also supports severa activities bility. Although clearly motivated by policy concerns, that, while not properly research projects, add to the value Bankresearchisusuallydriven notbytheimmediateneeds of Bank research and enhance the Bank's image as an of a particular Bank lending operation or a particular intellectual leader in the field of development research. -

Britten Connections a Guide for Performers and Programmers

Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Britten –Pears Foundation Telephone 01728 451 700 The Red House, Golf Lane, [email protected] Aldeburgh, Suffolk, IP15 5PZ www.brittenpears.org Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Contents The twentieth century’s Programming tips for 03 consummate musician 07 13 selected Britten works Britten connected 20 26 Timeline CD sampler tracks The Britten-Pears Foundation is grateful to Orchestra, Naxos, Nimbus Records, NMC the following for permission to use the Recordings, Onyx Classics. EMI recordings recordings featured on the CD sampler: BBC, are licensed courtesy of EMI Classics, Decca Classics, EMI Classics, Hyperion Records, www.emiclassics.com For full track details, 28 Lammas Records, London Philharmonic and all label websites, see pages 26-27. Index of featured works Front cover : Britten in 1938. Photo: Howard Coster © National Portrait Gallery, London. Above: Britten in his composition studio at The Red House, c1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton . 29 Further information Opposite left : Conducting a rehearsal, early 1950s. Opposite right : Demonstrating how to make 'slung mugs' sound like raindrops for Noye's Fludde , 1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton. Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers 03 The twentieth century's consummate musician In his tweed jackets and woollen ties, and When asked as a boy what he planned to be He had, of course, a great guide and mentor. with his plummy accent, country houses and when he grew up, Britten confidently The English composer Frank Bridge began royal connections, Benjamin Britten looked replied: ‘A composer.’ ‘But what else ?’ was the teaching composition to the teenage Britten every inch the English gentleman. -

Sinfonia Da Requiem, Op. 20 Benjamin Britten (1913–1976) Written: 1940 Movements: Three Style: Contemporary Duration: 20 Minutes

Sinfonia da Requiem, Op. 20 Benjamin Britten (1913–1976) Written: 1940 Movements: Three Style: Contemporary Duration: 20 minutes The composer Benjamin Britten left England for America in 1939 rather than become involved in the impending war. He returned to England in 1942 and registered as a conscientious objector. While in America, Britten received a strange commission from the government of Japan to write a piece to help celebrate the 2,600th anniversary of the founding of the Mikado dynasty. Britten reluctantly agreed as long as his work wouldn’t have to include any “musical jingoism.” He had already been considering writing a work to commemorate his parents, so he sent a proposal back. The Japanese agreed and in very short order, Britten wrote his Sinfonia da Requiem. He dedicated it to his parents and wrote “as anti-war as possible.” Upon seeing the final product, the Japanese rejected it and disinvited Britten. “We are afraid that the composer must have greatly misunderstood our desire . [it] has a melancholy tone both in its melodic pattern and rhythm, making it unsuitable for performance on such an occasion as our national ceremony,” they wrote. Britten also said they accused him of “providing a Christian work where Christianity was apparently unacceptable.” He provided these (here much abbreviated) comments about the piece for its premiere in 1941 in New York City: I. Lacrymosa. A slow marching lament in a persistent 6/8 rhythm with a strong tonal center on D. There are three main motives. The first section of the movement is quietly pulsating; the second is a long crescendo leading to a climax based on the first cello theme. -

Così Fan Tutte Cast Biography

Così fan tutte Cast Biography (Cahir, Ireland) Jennifer Davis is an alumna of the Jette Parker Young Artist Programme and has appeared at the Royal Opera, Covent Garden as Adina in L’Elisir d’Amore; Erste Dame in Die Zauberflöte; Ifigenia in Oreste; Arbate in Mitridate, re di Ponto; and Ines in Il Trovatore, among other roles. Following her sensational 2018 role debut as Elsa von Brabant in a new production of Lohengrin conducted by Andris Nelsons at the Royal Opera House, Davis has been propelled to international attention, winning praise for her gleaming, silvery tone, and dramatic characterisation of remarkable immediacy. (Sacramento, California) American Mezzo-soprano Irene Roberts continues to enjoy international acclaim as a singer of exceptional versatility and vocal suppleness. Following her “stunning and dramatically compelling” (SF Classical Voice) performances as Carmen at the San Francisco Opera in June, Roberts begins the 2016/2017 season in San Francisco as Bao Chai in the world premiere of Bright Sheng’s Dream of the Red Chamber. Currently in her second season with the Deutsche Oper Berlin, her upcoming assignments include four role debuts, beginning in November with her debut as Urbain in David Alden’s new production of Les Huguenots led by Michele Mariotti. She performs in her first Ring cycle in 2017 singing Waltraute in Die Walküre and the Second Norn in Götterdämmerung under the baton of Music Director Donald Runnicles, who also conducts her role debut as Hänsel in Hänsel und Gretel. Additional roles for Roberts this season include Rosina in Il barbiere di Siviglia, Fenena in Nabucco, Siebel in Faust, and the title role of Carmen at Deutsche Oper Berlin. -

Open the Door

Pittsburgh OPERA NEWS RELEASE CONTACT: LAURA WILLUMSEN (412) 281-0912 X 215 [email protected] PHOTOS: MAGGIE JOHNSON (412) 281-0912 X262 [email protected] Pittsburgh Opera opens 2007-2008 season: MADAMA BUTTERFLY by Puccini WHAT Puccini’s Madama Butterfly WHERE Benedum Center for the Performing Arts WHEN Saturday, October 13, 7:00 p.m.* Tuesday, October 16, 7:00 p.m. Friday, October 19, 8:00 p.m. Sunday, October 21, 2:00 p.m. * Note: The Sat, Oct 13 early start time is due to the Diamond Horseshoe Celebration. RUN TIME 2:45 with one intermission LANGUAGE Sung in Italian with English texts projected above the stage E TICKETS Start at $16. Call (412) 456-6666, visit www.pittsburghopera.org or purchase in person at the Theater Square box office at 665 Penn Avenue. Pittsburgh, PA (9/24/2007) . General director Mark Weinstein and artistic director Christopher Hahn announce the first opera of the 2007-2008 season, Puccini’s Madama Butterfly, in a shimmering production—it literally floats on water—from Opera Australia at the Sydney Opera House. While the production and conductor, music director Antony Walker, both hail from Down Under, Madama Butterfly’s dream cast blends American and international stars of the first magnitude: Chilean diva Verónica Villarroel, who has made Butterfly her signature role across the globe; and Chinese mezzo Zheng Cao, Suzuki in the 2002 Butterfly and Sesto in Giulio Cesare in 2004. A pair of Americans portray Pinkerton and Sharpless: Americans Frank Lopardo, who sang another bad- boy tenor as the Duke in Pittsburgh Opera’s Rigoletto in 2005 and makes his role debut as Pinkerton; and Earle Patriarco, a sensational Figaro here in The Barber of Seville in 2003. -

Billy Budd Composer Biography: Benjamin Britten

Billy Budd Composer Biography: Benjamin Britten Britten was born, by happy coincidence, on St. Cecilia's Day, at the family home in Lowestoft, Suffolk, England. His father was a dentist. He was the youngest of four children, with a brother, Robert (1907), and two sisters, Barbara (1902) and Beth (1909). He was educated locally, and studied, first, piano, and then, later, viola, from private teachers. He began to compose as early as 1919, and after about 1922, composed steadily until his death. At a concert in 1927, conducted by composer Frank Bridge, he met Bridge, later showed him several of his compositions, and ultimately Bridge took him on as a private pupil. After two years at Gresham's School in Holt, Norfolk, he entered the Royal College of Music in London (1930) where he studied composition with John Ireland and piano with Arthur Benjamin. During his stay at the RCM he won several prizes for his compositions. He completed a choral work, A Boy was Born, in 1933; at a rehearsal for a broadcast performance of the work by the BBC Singers, he met tenor Peter Pears, the beginning of a lifelong personal and professional relationship. (Many of Britten's solo songs, choral and operatic works feature the tenor voice, and Pears was the designated soloist at many of their premieres.) From about 1935 until the beginning of World War II, Britten did a great deal of composing for the GPO Film Unit, for BBC Radio, and for small, usually left-wing, theater groups in London. During this period he met and worked frequently with the poet W. -

Season 2013-2014

27 Season 2013-2014 Thursday, March 27, at 8:00 Friday, March 28, at 2:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, March 29, at 8:00 Donald Runnicles Conductor Tal Rosner Video Artist Janine Jansen Violin Britten Four Sea Interludes, Op. 33a, from Peter Grimes I. Dawn II. Sunday Morning III. Moonlight IV. Storm Video and animation by Tal Rosner Video co-commissioned by the New World Symphony, America’s Orchestral Academy; the Los Angeles Philharmonic Association; The Philadelphia Orchestra Association; and the San Francisco Symphony Britten Violin Concerto, Op. 15 I. Moderato con moto— II. Vivace— III. Passacaglia: Andante lento (un poco meno mosso) Intermission Pärt Cantus in Memory of Benjamin Britten First Philadelphia Orchestra performances Mozart Symphony No. 36 in C major, K. 425 (“Linz”) I. Adagio—Allegro spiritoso II. Andante III. Menuetto—Trio—Menuetto da capo IV. Presto This program runs approximately 1 hour, 50 minutes. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 228 Story Title The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra community itself. His concerts to perform in China, in 1973 is one of the preeminent of diverse repertoire attract at the request of President orchestras in the world, sold-out houses, and he has Nixon, today The Philadelphia renowned for its distinctive established a regular forum Orchestra boasts a new sound, desired for its for connecting with concert- partnership with the National keen ability to capture the goers through Post-Concert Centre for the Performing hearts and imaginations of Conversations. -

Billy Budd Cast Biographies

Billy Budd Cast Biographies William Burden sang George Bailey in San Francisco Opera’s West Coast premiere of Jake Heggie’s It’s a Wonderful Life in fall 2018. The American tenor made his San Francisco Opera debut in 1992 as Count Lerma in Don Carlo and has returned in roles including Laca in Jenůfa, Tom Rakewell in The Rake’s Progress and he created the roles of Dan Hill in Christopher Theofanidis’ Heart of a Soldier and Peter in Mark Adamo’s The Gospel of Mary Magdalene. An alumnus of the San Francisco Opera’s Merola Opera Program, Burden is a member of the voice faculty at The Juilliard School and the Mannes School of Music. Appearing in prestigious opera houses in the United States and Europe, his repertoire also includes the title roles of Les Contes d'Hoffmann, Faust, Pelléas et Mélisande, Roméo et Juliette, Béatrice and Bénédict, Candide, and Acis and Galatea; Loge in Das Rheingold, Aschenbach in Death in Venice, Florestan in Fidelio, Don José in Carmen, Pylade in Iphigénie en Tauride, Edgardo in Lucia di Lammermoor, Ferrando in Così fan tutte and Lensky in Eugene Onegin. A supporter of new works, he appeared in the U.S. premiere of Henze’s Phaedra at Opera Philadelphia and created the roles of George Bailey at Houston Grand Opera, Frank Harris in Theodore Morrison's Oscar at the Santa Fe Opera, Gilbert Griffiths in Tobias Picker’s An American Tragedy at the Metropolitan Opera, Dodge in Daron Hagen’s Amelia at Seattle Opera, Ruben Iglesias in Jimmy López's Bel Canto at Lyric Opera of Chicago, and Nikolaus Sprink in Kevin Puts’ Pulitzer Prize-winning Silent Night at Minnesota Opera. -

CHAN 3094 BOOK.Qxd 11/4/07 3:13 Pm Page 2

CHAN 3094 Book Cover.qxd 11/4/07 3:12 pm Page 1 CHAN 3094(2) CHANDOS O PERA IN ENGLISH PETER MOORES FOUNDATION CHAN 3094 BOOK.qxd 11/4/07 3:13 pm Page 2 Alban Berg (1885–1935) Wozzeck Opera in three acts (fifteen scenes), Op. 7 Libretto by Alban Berg after Georg Büchner’s play Woyzeck Lebrecht Collection Lebrecht English translation by Richard Stokes Wozzeck, a soldier.......................................................................................Andrew Shore baritone Drum Major .................................................................................................Alan Woodrow tenor Andres, a soldier...............................................................................................Peter Bronder tenor Captain ................................................................................................................Stuart Kale tenor Doctor .................................................................................................................Clive Bayley bass First Apprentice................................................................................Leslie John Flanagan baritone Second Apprentice..............................................................................................Iain Paterson bass The Idiot..................................................................................................John Graham-Hall tenor Marie ..........................................................................................Dame Josephine Barstow soprano Margret ..................................................................................................Jean -

Donald Runnicles Leads Cso in Program of Works by Elgar, Strauss, and Britten

For Immediate Release: Press Contacts: April 29, 2016 Eileen Chambers, 312-294-3092 Photos Available By Request [email protected] DONALD RUNNICLES LEADS CSO IN PROGRAM OF WORKS BY ELGAR, STRAUSS, AND BRITTEN May 5, 7 and 10, 2016 CHICAGO—Conductor Donald Runnicles leads the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO) in concerts on Thursday, May 5, at 8:00 p.m., Saturday, May 7, at 8:00 p.m., and Tuesday, May 10, at 7:30 p.m. The program includes Benjamin Britten’s Sinfonia da requiem, Richard Strauss’ gripping tone poem Death and Transfiguration, and Edward Elgar’s Enigma Variations. Britten’s Sinfonia da requiem, opens the program. Written in 1940 as a commission for the 2600th anniversary celebrations of the Japanese emperor Hirohito’s ruling dynasty, the piece went unused for the occasion due to its notably mournful tone. Britten’s beautifully orchestrated and strikingly powerful work was later premiered by the New York Philharmonic in Carnegie Hall in 1941. The program continues with one of Richard Strauss’ early tone poems, Death and Transfiguration, which traces a man’s journey through the pain of death to his eventual redemption. Concluding the evening’s program is Elgar’s Variations on an Original Theme, Op. 36 (Enigma) which contains 14 charming and witty musical portraits of the composer’s circle of acquaintances and one of Elgar himself. Arguably one of the most popular English classical works of the 20th century, the Enigma Variations was given its U.S. premiere by the CSO in 1902. Internationally renowned conductor Donald Runnicles serves as General Music Director of the Deutsche Oper Berlin, Chief Conductor of BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, and Music Director of the Grand Teton Music Festival, as well as Principal Guest Conductor with the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra.