Nguna-Pele Marine and Land Protected Area Network

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Status of the Dugong (Dugon Dugon) in Vanuatu

ORIGINAL: ENGLISH SOUTH PACIFIC REGIONAL ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMME TOPIC REVIEW No. 37 THE STATUS OF THE DUGONG (DUGON DUGON) IN VANUATU M.R. Chambers, E.Bani and B.E.T. Barker-Hudson O.,;^, /ZO. ^ ll pUG-^Y^ South Pacific Commission Noumea, New Caledonia April 1989 UBHArt/ SOUTH PACIFIC COMMISSION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This project was carried out to assess the distribution, abundance, cultural importance and threats to the dugong in Vanuatu. The study was carried out by a postal questionnaire survey and an aerial survey, commencing in October 1987. About 600 copies of the questionnaire were circulated in Vanuatu, and about 1000 kilometres of coastline surveyed from the air. Dugongs were reported or seen to occur in nearly 100 localities, including all the major islands and island groups of Vanuatu. The animals were generally reported to occur in small groups; only in three instances were groups of more than 10 animals reported. Most people reported that dugong numbers were either unchanged or were increasing. There was no evidence that dugongs migrate large distances or between islands in the archipelago, although movements may occur along the coasts of islands and between closely associated islands. Dugong hunting was reported from only a few localities, although it is caught in more areas if the chance occurs. Most hunting methods use traditional means, mainly the spear. Overall, hunting mortality is low, even in areas reported to regularly hunt dugongs. Accordingly, the dugong does not seem to be an important component of the subsistence diet in any part of Vanuatu, even though it is killed mainly for food. -

Shefa Province Skills Plan 2015 - 2018

SHEFA PROVINCE SKILLS PLAN 2015 - 2018 Skills for Economic Growth CONTENTS Abbreviations 2 Forward by the Shefa Secretary General 3 1 Introduction 4 2 Vanuatu Training Landscape 6 3 Purpose 8 4 Shefa Province 9 5 Agriculture and Horticulture Sectors 12 6 Forestry Sector 18 7 Livestock Sector 21 8 Fisheries and Aquaculture Sector 25 9 Tourism and Hospitality Sector 28 10 Construction and Property Services Sector 32 11 Transport and Logistics Sector 37 12 Cross Sector 40 Appendix 1: Employability and Generic Skills 46 Appendix 2: Acknowledgments 49 ABBREVIATIONS BDS Business Development Services FAD Fish Aggregating Device FMA Fisheries Management Act GESI Gender Equity and Social Inclusion MoALFFBS Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Forestry, Fisheries and Bio-Security MoET Ministry of Education and Training NGO Non-Government Organisations PSET Post School Education and Training PTB Provincial Training Boards TVET Technical and Vocational Education and Training VAC Vanuatu Agriculture College VCCI Vanuatu Chamber of Commerce and Industry VESSP Vanuatu Education Sector Strategic Plan VIT Vanuatu Institute of Technology VQA Vanuatu Qualifi cations Authority FORWARD BY THE SHEFA SECRETARY GENERAL - MR MICHEL KALWORAI It is with much pleasure that I present to you our fi rst Skills Plan for Shefa Province; it specifi cally captures our training and learning development projections for four years, commencing this year 2015 and concluding in 2018. It also draws from, and refl ects, the Shefa Province Corporate Plan. It will be skill development that will assist us in improving and developing new infrastructure that will benefi t all in the province. It will drive the efforts of industry sectors seeking to achieve their commercial potential, in particular our agriculture and tourism sectors, both of which are seeking to improve productivity by having a skilled and qualifi ed workforce. -

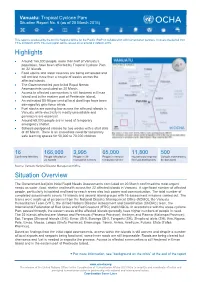

OCHA VUT Tcpam Sitrep6 20

Vanuatu: Tropical Cyclone Pam Situation Report No. 6 (as of 20 March 2015) This report is produced by the OCHA Regional Office for the Pacific (ROP) in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It covers the period from 19 to 20 March 2015. The next report will be issued on or around 21 March 2015. Highlights Around 166,000 people, more than half of Vanuatu’s population, have been affected by Tropical Cyclone Pam on 22 islands. Food stocks and water reserves are being exhausted and will not last more than a couple of weeks across the affected islands. The Government-led joint Initial Rapid Needs Assessments concluded on 20 March. Access to affected communities is still hindered in Emae Island and in the eastern part of Pentecote Island. An estimated 50-90 per cent of local dwellings have been damaged by gale-force winds. Fuel stocks are running low across the affected islands in Vanuatu while electricity is mostly unavailable and generators are essential. Around 65,000 people are in need of temporary emergency shelter. Schools postponed classes for two weeks with a start date of 30 March. There is an immediate need for temporary safe learning spaces for 50,000 to 70,000 children. 16 166,000 3,995 65,000 11,800 500 Confirmed fatalities People affected on People in 39 People in need of Households targeted Schools estimated to 22 islands evacuation centres temporary shelter for food distributions be damaged Source: Vanuatu National Disaster Management Office Situation Overview The Government-led joint Initial Rapid Needs Assessments concluded on 20 March confirmed the most urgent needs as water, food, shelter and health across the 22 affected islands in Vanuatu. -

Kastom and Conservation: a Case Study of the Nguna-Pele Marine

KASTOM AND CONSERVATION: A CASE STUDY OF THE NGUNA-PELE MARINE PROTECTED AREA NETWORK by DANYEL ADDES (Under the Direction of Peter Brosius) ABSTRACT In Vanuatu, the Melanesian archipelago formally known as New Hebrides, traditional marine tenure has become a center piece of marine conservation efforts. However, its influence is relatively slight in the area of the Nguna-Pele Marine Protected Area Network (NPMPA), a village-based conservation organization. The NPMPA has therefore adopted a westernized conservation model of Marine Protected Areas, or MPAs. As it pursues its conservation goals, the NPMPA must continually negotiate between the expectations, tools, and methodologies, of two powerful normative discourses: traditional knowledge and national indigenous identity, and marine biology and conservation ecology. This case study uses discourse analysis to investigate the interactions of western conservation discourse and traditional forms of knowledge surrounding the management of marine resources. Findings suggest that the adaptation of western conservation practice has resulted in conservation discourse that situates agency in documents and conservation tools more often than in human action. INDEX WORDS: Ecological and Environmental Knowledge, Traditional Knowledge, Marine Conservation, Melanesia, Discourse Analysis KASTOM AND CONSERVATION: A CASE STUDY OF THE NGUNA-PELE MARINE PROTECTED AREA NETWORK by DANYEL ADDES B.A., University of Massachusetts, 2004 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in -

The Search for the Elusive Female Chiefs of Vanuatu

TheSearch for the ELUSIVE FEMALE CHIEFS OF VA N U A T U Story by Lew Toulmin, lead author, and co-authors Dalsie Baniala, Michael Wyrick, Sophie Hollingsworth, Daniel Huang, Theresa Menders and Corey Huber. or over 100 years, researchers, down to the present. ment the female chiefs of Maewo. Dalsie writers and anthropologists So I was quite shocked when over pizza would organize an island festival for the have agreed that there are at Nambawan Café a couple of years women chiefs of the island, featuring no female chiefs in Vanuatu ago, my friend (and now the Vanuatu their culture, traditions, ceremonies and or even Melanesia. Writing Telecom Regulator) Dalsie Baniala casu- promotions. I would bring in and lead in 1914, William Rivers in his History of ally mentioned that her sister on Maewo a team of researchers, to undertake the FMelanesian Society stated that on Pente- analysis. The festival was scheduled for was a “female chief.” I said, “That is not cost, females had prefixes to their names possible – there are none!” August 2015. indicating differences in rank, but he And so the search for the elusive female Then Cyclone Pam hit, in March 2015. firmly stated that this was “not connect- chiefs of Vanuatu began. The festival was postponed to August ed with any organization resembling the 2016, and morphed into more of an We agreed to launch an Expedition, Sukwe” – the male chiefly system. And all-island event focused on women’s arts sanctioned by the famous Explorers Club this was the closest that women came to and traditional practices. -

Justice Poor

JUSTICEfor the RESEARCH REPORT POOR SEPTEMBER 2010 Promoting equity and managing conflict in development Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Significant land loss was a unifying factor and mobilizing force behind Vanuatu’s independence movement, a key demand of which was the return of WAN LIS, FULAP STORI alienated land to custom landholders. The continuing alienation and use of land in Vanuatu remains an important source of conflict. Leasing plays a central role in contemporary alienation of customary land and is a common source of complaint. The formal legal framework for leasing fails to take into account LEASING ON EPI ISLAND, VANUATU Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized many of the local particularities of land holding and a lack of proper advice about the regulatory framework contributes to inequitable outcomes for landholders. In partnership with the Government and landholders, J4P explores these issues through in-depth research which provides evidence of the continuing uncertainty about land leasing and benefit distribution and its implications for group decision making. Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Justice for the Poor is a World Bank research and development program aimed at informing, designing WAN LIS, FULAP STORI and supporting pro-poor approaches to justice reform. LEASING ON EPI ISLAND, VANUATU Public Disclosure Authorized RAEWYNPublic Disclosure Authorized PORTER AND ROD NIXON www.worldbank.org/justiceforthepoor WanLis_Cover_Sep16.indd 1 9/20/2010 3:07:41 PM Justice for the Poor is a World Bank research and development program aimed at informing, designing and supporting pro-poor approaches to justice reform. It is an approach to justice reform which sees justice from the perspective of the poor and marginalized, is grounded in social and cultural contexts, recognizes the importance of demand in building equitable justice systems, and understands justice as a cross-sectoral issue. -

South Malekula Area Council; Malampa Province

V-CAP site: South Malekula Area Council, Malampa Province South Malekula Area Council; Malampa Province 1 V-CAP site context and background Malampa is one of the six provinces of Vanuatu, located in the centre of the country and consisting of three main islands namely Malekula, Ambrym and Paama. It also includes a number of smaller offshore islands – the small islands of Uripiv, Norsup, Rano, Wala, Atchin and Vao off the coast of Malekula and the volcanic island of Lopevi near Paama (currently uninhabited). Also included are the Maskelynne Islands and other small islands suck as Akam and Avock along the south coast of Malekula. The total population of Malampa Province is 36,722 (2009 census) people and it contains an area of 2,779 km². Malekula is the most populated and developed island in the province and houses the provincial capital named Lakatoro. Malekula receives an abundance of precipitation. The temperature on the island varies during the hot and cold seasons, but averages approximately 24.9°C at the coast and is a few degrees cooler in the centre of the island. Weather in Malekula is seasonal, and warmer from November until April and cooler and dryer period typically from May to October. Like the rest of Vanuatu, the island’s weather is strongly influenced by the El Nino Southern Oscillation cycles. During the El Nino (warm phase) the country is subject to long dry spells. During the La Nina (cool phase) Vanuatu has prolonged wet conditions. Malekula is located on active geological faults. The southeastern side of the island experienced major earthquakes as recently as the 1990s and the land, e.g. -

Highlights Situation Overview

Vanuatu: Tropical Cyclone Pam Situation Report No. 4 (as of 18 March 2015) This report is produced by the OCHA Regional Office for the Pacific (ROP) in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It covers the period from 17 to 18 March 2015. The next report will be issued on or around 19 March 2015. Highlights The Government-led joint Initial Rapid Needs Assessments continued today, indicating an urgent need for food, water, medical supplies, hygiene kits, kitchen kits, tents and bedding. Emerging aerial images confirm total or near-total destruction of homes, buildings and crops. A total of 34 schools are being used as evacuation centres on Efate Island and the provinces of Torba and Penama, which prevents children from attending school. Food supplies in affected areas, particularly in Erromango, are running critically low. Medicines, body bags and power supplies for hospitals are urgently required. An estimated 60 per cent of the population in Shefa and Tafea provinces has no access to drinking water. 11 3,026 36 Confirmed fatalities People in evacuation Evacuation centres centres in Efate in Efate Source: Vanuatu National Disaster Management Office Situation Overview Government-led joint Initial Rapid Needs Assessments have continued, broadening the reach to include islands in Erromango and Tanna islands (Tafea Province), Emae, Tongoa and Epi islands (Shefa Province), West Ambrym island (Malampa Province) and Pentecote island (Penama Province). The information collected will inform further response decisions. On 18 March, a 12-person team travelled to Tanna in Tafea province. The team consisted of specialists from health, WASH, shelter, food and agriculture, education and protection sectors, as well as medical staff from Vanuatu and Australia. -

OP6 SGP Vanuatu Country Programme Strategy

VANUATU SGP C OUNTRY P ROGRAMME S TRATEGY FOR OP6 201 5 - 2018 P REPARED BY : V ANESSA O RGANO , L EAH N IMOHO , R OLENAS B AERALEO AND D ONNA K ALFATAK R EVIEWED AND APPROVED BY THE NSC: R EVIEW ED AND APPROVED BY CPMT: 1 Table of Contents Background ………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 Section 1: SGP countr y programme - summary background……………………………………………. 4 Section 2: SGP country programme niche………………………………………………………………… 5 Section 3: OP6 strategies .... ……………………………………………………………………………….. 19 Section 4: Expected results framework …………………………………………………………………...3 7 Section 5: Monitoring and evaluation plan ………………………………………………………………. 4 3 Section 6: Resource mobilization plan ……………………………………………… ……………………. 4 6 Section 7: Risk management plan ………………………………………………………………………… 4 7 Section 8: National Steering Committee endorsement ………………………………………………….. 49 Annex 1: OP6 landscape/seascape baseline assessment 2 COUNTRY : VANUATU OP6 resources (estimated US$ ) 1 a. Core funds: TBD b. OP5 remaining balance: OP5 Small Grants Programme funds finished c. STAR funds: Total of $ 6 .2 million consisting of: Government of Vanuatu climate change projects (supported by UNDP): $ 3 million Government of Vanuatu land degradation projects (supported by FAO) : $ 1 million Government of Vanuatu biod iversity projects (supported by IUCN) : $ 2 .6 million d. Other Funds to be mobilized: AusAID SIDS CBA: $210,000 available from OP5 due to be committed by December 2016 Background : As a GEF corporate programme, SGP aligns its operational phase strategies to that of the GEF , and provides a series of demonstration projects for further scaling up , replication and mainstreaming . Action at the local level by civil society, indigenous peoples and l ocal communities is deemed a vital component of the GEF 20/20 Strategy (i.e. -

Ambae Volcano Eruption

Emergency Plan of Action Operation Update Vanuatu: Ambae Volcano Eruption DREF n° MDRVU005 GLIDE n° VO-2017-000140-VUT DREF operation update n° 2 Timeframe covered by this update: Issued: 30 January 2018 25 September 2017 - 31 December 2017 Operation start date: 25 September 2017 Operation timeframe: 6 months (extended from 4 months) Overall operation budget: CHF 255,278 Operation end date: 31 March 2018 N° of people being assisted: 11,000 Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners currently actively involved in the operation: The Vanuatu Red Cross Society (VRCS) works with the following RCRC partners: Australian Red Cross; French Red Cross; New Zealand Red Cross; and the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) country cluster support team – Pacific, IFRC as co-lead of the Vanuatu Shelter Cluster. Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: The Government of the Republic of Vanuatu through the Vanuatu National Disaster Management Office (NDMO) activated the National Emergency Operations Centre (National EOC) and has been coordinating the response. The Joint Police Operations Centre (JPOC) was also activated and the Vanuatu Police Force and Vanuatu Mobile Force have been supporting the operations with logistics and transportation, as well as security in the evacuation centres. Provincial Governments activated their Provincial Emergency Operation Centre (PEOC)and respective Provincial Disaster Committees to lead the operation on the ground. In Sanma province the WASH, Shelter, Gender, Logistic, FSAC and Protection Cluster with the assistance from its National and international cluster leads (i.e: UNICEF with WASH Cluster, CARE international and Save the Children for Gender and Protection, and IOM. -

Community-Based Adaptation to Climate Change: Lessons from Tanna Island, Vanuatu

Island Studies Journal, 14(1), 2019, 59-80 Community-based adaptation to climate change: lessons from Tanna Island, Vanuatu Tahlia Clarke School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia [email protected] Karen E. McNamara School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia [email protected] (corresponding author) Rachel Clissold School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia [email protected] Patrick D. Nunn School of Social Sciences, University of the Sunshine Coast, Sippy Downs, Australia [email protected] Abstract: Community-based adaptation has gained significant international attention as a way for communities to respond to the increasing threats and complex pressures posed by climate change. This bottom-up strategy represents an alternative to the prolonged reliance on, and widespread ineffectiveness of, mitigation methods to halt climate change, in addition to the exacerbation of vulnerability resulting from top-down adaptation approaches. Yet despite the promises of this alternative approach, the efficacy of community-based adaptation remains unknown. Its potential to reduce vulnerability within communities remains a significant gap in knowledge, largely due to limited participatory evaluations with those directly affected by these initiatives, to determine the success and failure of project design, implementation, outcomes and long-term impact. This paper seeks to close this gap by undertaking an in-depth evaluation of multiple community-based adaptation projects in Tanna Island, Vanuatu and exploring community attitudes and behavioural changes. This study found that future community-based adaptation should integrate contextual specificities and gender equality frameworks into community-based adaptation design and implementation, as well as recognise and complement characteristics of local resilience and innovation. -

Port Vila Ecosystems, Climate Change and Development Scenarios 23

Ecosystems, Climate Change PORT VILA and Development Scenarios V A N U A T U 2.4.2 Coastal Available results for coastal ecosystem services provision and demand are limited to coral reef habitats. Table 2.8 is derived from diving surveys to derive percent coral cover, personal communications from Port Vila workshop participants, divers, and other interested persons, and author’s personal knowledge. Figure 2.9 Vanuatu coral reef 2.4.2.1 Diver questionnaire Four diving instructors from two recreational diving companies in Port Vila were interviewed. Three divers had been diving regularly in Port Vila for over twenty years, and the fourth for six months. All divers had extensive knowledge of coral and fish species in Port Vila, and an adequate to good understanding of reef ecosystems. The divers were asked questions regarding their perception of coral condition, fish and seagrass abundance, as well as trends and threats to the ecosystems they dive in. The divers were asked to rate reef condition as poor, medium or high for all dive sites. Sites with less than a quarter (25%) live coral cover were classified as poor. Sites with over 70% live coral cover were classified as high. For each reef, the diver ratings were compared, and where there was congruence with three or more perspectives, this rating was used. PORT VILA ECOSYSTEMS, CLIMATE CHANGE AND DEVELOPMENT SCENARIOS 23 SPREP Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Blaschke, Paul M … [et al.] Port Vila. Ecosystems, Climate Change and Development Scenarios, Vanuatu. Apia, Samoa: SPREP, 2017. 96 p. 29 cm. ISBN: 978-982-04-0739-8 (print) 978-982-04-0740-4 (ecopy) 1.