Supreme Court, Appellate Division First Department

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Association of Medical Examiners, Executive Committee, July 2, 2009

Suprems Court, U.S. FILED No. 13-735 JAN\ 1 201't OFPICE OF THE CLERK Jn tltbt &upreme ~ourt of tbe Wniteb &tate~ --------·-------- EFREN MEDINA, Petitioner, v. ARIZONA, Respondent. --------·-------- On Petition For Writ Of Certiorari To The Supreme Court Of Arizona --------·-------- BRIEF OF THE INNOCENCE NETWORK AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER --------·-------- STEPHEN A. MILLER Counsel of Record BRIAN KINT COZEN O'CONNOR 1900 Market Street Philadelphia, PA 19103 (215) 665-2000 [email protected] BARRY C. SCHECK M. CHRIS FABRICANT PETER MORENO INNOCENCE NETWORK, INC. 100 Fifth Avenue, 3rd Floor New York, NY 10011 (212) 364-5340 COCKLE LEGAL BRIEFS 18001225-6964 WWW.COCKLELEGALBRIEFS.COM BLANK PAGE 1 CAPITAL CASE QUESTION PRESENTED Amicus Curiae adopts and incorporates the ques tion presented by Petitioner. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE...................... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT.............................. 3 ARGUMENT........................................................ 5 I. THE CURRENT SYSTEM IMPORTS FLAWED, TESTIMONIAL STATEMENTS INTO AUTOPSY REPORTS ....................... 5 A. The contents of autopsy reports are inherently testimonial......................... 5 B. The current death investigation sys tem undermines the veracity of au topsy reports........................................ 6 (1) Dr. Thomas Gill . 8 (2) Dr. Stephen Hayne . 9 (3) Ralph Erdmann.............................. 11 C. Forensic pathology is particularly susceptible to cognitive bias and sug gestion by law enforcement................. 11 II. CONFRONTATION OF THE AUTHORS OF FLAWED TESTIMONIAL STATE MENTS IN AUTOPSY REPORTS SERVES THE INTERESTS OF JUSTICE .................. 18 A. Surrogate testimony allows law en forcement officials to cover up cogni tive bias and forensic fraud................. 18 B. Errors concerning the time, manner, and cause of death are major factors in wrongful convictions . -

Robert Morgenthau, Longtime Manhattan District Attorney, Dies at 99

Robert Morgenthau, Longtime Manhattan District Attorney, Dies at 99 By Robert D. McFadden July 21, 2019 Robert M. Morgenthau, a courtly Knickerbocker patrician who waged war on crime for more than four decades as the chief federal prosecutor for Southern New York State and as Manhattan’s longest-serving district attorney, died on Sunday in Manhattan. He was 99. Mr. Morgenthau’s wife, Lucinda Franks, said he died at Lenox Hill Hospital after a short illness. In an era of notorious Wall Street chicanery and often dangerous streets, Mr. Morgenthau was the bane of mobsters, crooked politicians and corporate greed; a public avenger to killers, rapists and drug dealers; and a confidant of mayors and governors, who came and went while he stayed on — for nearly nine years in the 1960s as the United States attorney for the Southern District of New York and for 35 more as Gotham’s aristocratic Mr. District Attorney. For a Morgenthau — the scion of a family steeped in wealth, privilege and public service — he was strangely awkward, a wooden speaker who seemed painfully shy on the stump. His grandfather had been an ambassador in President Woodrow Wilson’s day, and his father was President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s treasury secretary. His own early political forays, two runs for governor of New York, ended disastrously. But from Jan. 1, 1975, when he took over from an interim successor to the legendary district attorney Frank S. Hogan, to Dec. 31, 2009, when he finally gave up his office in the old Criminal Courts Building on the edge of Chinatown, Mr. -

In Brief Law School Publications

Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons In Brief Law School Publications 1982 In Brief Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/in_brief Recommended Citation In Brief, iss. 24 (1982). https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/in_brief/24 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Publications at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in In Brief by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Law Alumni News Bulletin Case Western Reserve University Autumn, 1982 in brief Number 24 Published by the Case Western Reserve A Letter University School of Law for alumni, students, faculty, and friends Editor from the Anne M. McIntyre Law Alumni Office Faculty Editor Dean Wilbur C. Leatherberry Professor of Law September 1,1982 Two months ago, I began my service as dean of the Law School, and I want to share some thoughts with you. The Law School first two months have been busy for me Alumni Association and the faculty as we have become 1982-83 Officers more closely acquainted. I have also Charles R. Ault, '51 visited with alumni in Cleveland (sever President al law firms and a luncheon meeting an exciting time. The air is full of talk about curricular reform (Is our writing Fred D. Kidder, '50 with alumni in April), Washington, Vice President D.C. (a small group in August and a program intense enough? Is it effective in teaching needed writing skills?), re Richard C. -

Virtual Awards and Installation Ceremony 85Th Anniversary Party

NYWBA Annual Luncheon and 20th Anniversary Celebration, 1955, Hotel Sheraton Astor VIRTUAL AWARDS AND INSTALLATION CEREMONY 85TH ANNIVERSARY PARTY JUNE 9, 2020 $OWRQ6WHUOLQJ 6WHSKRQ&ODUN 3KLODQGR&DVWLOH 7RQ\0F'DGH -RQDWKDQ)HUUHOO -HUHP\0F'ROH 7DPLU5LFH 6DQGUD%ODQG 7HUHQFH&UXWFKHU /DTXDQ0F'RQDOG (ULF+DUULV $QWZRQ5RVH %UHRQQD7D\ORU %RWKDP-HDQ 5XPDLQ%ULVERQ (-%UDGIRUG 'DULXV7DUYHU 3KLOOLS:KLWH :LOOLDP*UHHQ 7HUUDQFH)UDQNOLQ $ULDQH0F&UHH *HRUJH)OR\G0LOHV+DOO $PDGRX'LDOOR (PPHWW7LOO :LOOLH0F&R\ -DPDU&ODUN $KPDXG$UEHU\ -HUDPH5HLG -RUGDQ%DNHU $NDL*XUOH\ 6HDQ%HOO (ULF*DUQHU )UHGGLH*UD\ 7UD\YRQ0DUWLQ 6WHYHQ'HPDUFR7D\ORU &KULVWRSKHU:KLWéHOG 6HDQ5HHG -DPHH-RKQVRQ $QWKRQ\+LOO 5DPDUOH\*UDKDP $WDWLDQD-HIIHUVRQ 'HÐ9RQ%DLOH\ 7RQ\5RELQVRQ "We must take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented. Sometimes we must inter- fere. When human lives are endan- gered, when human dignity is in jeop- ardy, national borders and sensitivities become irrelevant. Wherever men and women are persecuted because of their race, religion, or political views, that place must – at that moment – become the center of the universe." Elie Wiesel OUTGOING PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE As I write my last message as step down and leave our Association in the hands President of our great of Incoming President, Amanda B. Norejko, and Association—indeed celebrat- the Officers and Directors being sworn in, and am ing its 85th Anniversary—I can- thrilled to be presenting Michael W. Appelbaum not help but marvel at how over with the Doris S. Hoffman Service Award. For those the past two years I have been who do not know Michael, he is a long-standing constantly energized, activated member of NYWBA and Board member who has and inspired by our mission as chaired the Judiciary, Membership and Dinner well as challenged, tested and Committees—each of which is integral to our at times worn down by the magnitude of COVID-19, Association. -

Continuous Quality Improvement: Increasing Criminal Prosecution Reliability Through Statewide Systematic Improvement Procedures

LCB_20_3_Art_07_Cutino_Complete (Do Not Delete) 10/24/2016 8:30 AM CONTINUOUS QUALITY IMPROVEMENT: INCREASING CRIMINAL PROSECUTION RELIABILITY THROUGH STATEWIDE SYSTEMATIC IMPROVEMENT PROCEDURES by Josh Cutino * Several district attorney offices have established conviction integrity units and instituted programmatic reform as a result of wrongful convictions. However, reform only as a result of a wrongful conviction misses count- less opportunities to reduce errors, identify best practices, and improve processes. This Comment explores various organizational models to re- duce error and capture best practices in an effort to assist district attor- neys in bolstering the effectiveness, efficiency, and reliability of criminal prosecutions. Ultimately, district attorneys should establish systematic procedures for assessing errors and improving internal processes. Part II describes various conviction integrity unit models created by district at- torneys. Part III introduces the sentinel-event review process as a means of reducing error. Part IV describes different organizational procedures for institutionalizing and distributing best practices, such as the U.S. Air Force and New York State’s criminal justice Best Practices Commit- tee. I conclude in Part V by arguing that district attorneys should learn from these various programs, partner with police agencies and other stakeholders, and establish statewide organizations to capture and dis- seminate best practices. I. Introduction ............................................................................ -

New York County Supreme Court, Criminal Term

It is desirable that the trial of causes of action should take place under the public eye, not because the controversies of one citizen with another are of public concern, but because it is of the highest moment that those who administer justice should always act under the sense of public responsibility, and that every citizen should be able to satisfy himself with his own eyes as to the mode in which a public duty is performed. Justice Oliver Wendell Homes Cowley v. Pulsifer 137 Mass. 392, 294 (Mass. 1884) The Fund for Modern Courts is a private, nonprofit, nonpartisan organization dedicated to improving the administration of justice in New York. Founded in 1955, and led by concerned citizens, prominent lawyers, and leaders of the business community, Modern Courts works to make the court system more accessible, efficient, and user-friendly for all New Yorkers. The centerpiece of Modern Courts' efforts is our groundbreaking citizen court monitoring program, which gives citizens a powerful voice in how their court system is run. Our monitors, who now number more than 600 in over a dozen counties throughout New York State, have succeeded in obtaining numerous tangible improvements in the state’s courts. This report details the findings of our citizen court monitors and student monitors from the City University of New York’s John Jay College of Criminal Justice regarding the Criminal Term of the Supreme Court in New York County. For additional information, please contact: The Fund for Modern Courts, Inc. 351 West 54th Street New York, New York 10019 Telephone: (212) 541-6741 Fax: (212) 541-7301 E-Mail: [email protected] Disclaimer: The Fund for Modern Courts and its citizen court monitors do not endorse candidates for any purpose. -

In Brief Law School Publications

Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons In Brief Law School Publications 1994 In Brief Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/in_brief Recommended Citation In Brief, iss. 62 (1994). https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/in_brief/61 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Publications at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in In Brief by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Kf /^7r inLaw Alumni News Bulletin briefSeptember 1994 in brief Number 62 Inside this issue ... Published three times a year by the Case Western Reserve University School of Law for alumni, students, faculty, and friends. Editor Kerstin Ekfelt Trawick Commencement 1994 Director of Publications Faculty Editor Wilbur C. Leatherberry Professor of Law Associate Dean for Academic Affairs Contributing Editor John M. Nolan Director of Alumni Services Topping Off Photographers Mike Sands Kerstin Ekfelt Trawick Focus on Phoenix Law School Administration Peter M. Gerhart (216) 368-3283 Dean Daniel T. Clancy (216) 368-3308 Associate Dean for External Affairs Wilbur C. Leatherberry (216) 368-3585 Associate Dean for Academic Affairs JoAnne Urban Jackson (216) 368-5139 1 A Eastwood ’96 Associate Dean for Student At on a Trip to China and Administrative Affairs Barbara F. Andelmcm (216) 368-3600 Assistant Dean for Admission and Financial Aid Debra Fink (216)368-6353 Director of Career Services Kerstin Ekfelt Trawick (216) 368-6352 Director of Publications 18 New Benchers Elected John M. -

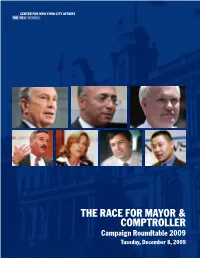

The Race for Mayor & Comptroller

The Race foR mayoR & comptrolleR campaign Roundtable 2009 Tuesday, December 8, 2009 THE RACE FOR COMPTROLLER AND MAYOR: CAMPAIGN ROUNDTABLE 2009 was made possible thanks to the generous support of the Dyson Foundation Milano also wishes to thank the following for their help in planning and coordinating this event: Alec Hamilton, Carin Mirowitz, Anna Schneider and Andrew White of the Center for New York City Affairs; Louis Dorff of Milano; and Tracy Jackson and Fred Hochberg formerly of Milano. Copyediting by Lisa DeLisle. This publication is available on the web at: www.newschool.edu/milano/docs/Campaign_Roundtable_2009.pdf For further information or to obtain copies of this report, please contact: Center for New York City Affairs Milano The New School for Management and Urban Policy 72 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10011 212.229.5418, fax 212.229.5335 [email protected] www.centernyc.org Edited Transcript Bill Thompson cover photo courtesy of his campaign. All other cover photos by the New York Daily News. All roundtable photos by Marty Heitner. The Race for Mayor and Comptroller: 2009 Campaign Roundtable Tuesday, December 8, 2009 The Center for New York City Affairs is dedicated to advancing innovative public policies that strengthen neighborhoods, support families and reduce urban poverty. Our tools include rigorous analysis; skillful journalistic research; candid public dialogue with stakeholders, and strategic planning with government officials, nonprofit practitioners and community residents. Andrew White, Director www.centernyc.org The Race for GOVernor and Comptroller: Campaign Roundtable 2009 Table of ContentS Letter from the Dean . iv Forward . .v Roundtable Program . vii Edited TranScript, SeSSion I: The Race for Comptroller Who’s Who . -

New York Criminal Law Newsletter a Publication of the Criminal Justice Section of the New York State Bar Association

NYSBA SPRING 2012 | VOL. 10 | NO. 2 New York Criminal Law Newsletter A publication of the Criminal Justice Section of the New York State Bar Association Photo of Members at Annual Luncheon See Centerfold for Additional Photos of Annual Luncheon and CLE Program NEW YORK STATE BAR ASSOCIATION From the NYSBA Book Store > Section Members get 20% discount* with coupon code Criminal Law PUB1390N and Practice Includes Forms on CD The Criminal Law and Practice monograph has been AUTHORS updated and redesigned and is now part of the New York Lawrence H. Gray, Esq. Lawyers’ Practical Skills Series.** Former Special Assistant Attorney General New York State Offi ce of the Covering the offenses and crimes that the general Attorney General practitioner is most likely to encounter, this practice guide addresses pretrial motions, motions to suppress evidence Hon. Leslie Crocker Snyder of an identifi cation, motions to suppress physical evidence, Special Narcotics Part New York, NY pretrial issues, special problems in narcotics cases, and more. Hon. Alex M. Calabrese Red Hook Community Justice Center The 2011-2012 release is current through the 2011 New Brooklyn, NY York legislative session. PRODUCT INFO AND PRICES 2011-2012 • 152 pp., softbound • PN: 406491 Order multiple titles to take advantage of our low fl at rate shipping charge of $5.95 per order, regard- NYSBA Members $90 less of the number of items shipped. $5.95 shipping and handling offer applies to orders shipped within the continental U.S. Shipping and handling charges for orders shipped outside the continental U.S. Non-members $105 will be based on destination and added to your total. -

Determination of Censure

STATE OF NEW YORK COMMISSION ON JUDICIAL CONDUCT In the Matter ofthe Proceeding Pursuant to Section 44, subdivision 4, ofthe Judiciary Law in Relation to DETERMINATION MICHAEL R. AMBRECHT, a Judge ofthe Court ofClaims and Acting Justice ofthe Supreme Court, New York County. THE COMMISSION: Honorable Thomas A. Klonick, Chair Stephen R. Coffey, Esq., Vice Chair Joseph W. Belluck, Esq. Colleen C. DiPirro Richard D. Emery, Esq. Paul B. Harding, Esq. Elizabeth B. Hubbard Marvin E. Jacob, Esq. Honorable Jill Konviser Honorable Karen K. Peters Honorable Terry Jane Ruderman APPEARANCES: Robert H. Tembeckjian (Edward Lindner and Brenda Correa, OfCounsel) for the Commission Martin & Obermaier LLC (by John S. Martin, Jr.), Olshan Grundman Frome Rosenzweig & Wolosky LLP (by Jeffrey A. Udell), and Joseph W. Bellacosa for the Respondent The respondent, Michael R. Ambrecht, a Judge ofthe Court ofClaims and an Acting Justice ofthe Supreme Court, New York County, was served with a Formal Written Complaint dated February 12,2007, containing two charges. The Formal Written Complaint alleged that respondent initiated an investigation and issued an opinion which were or appeared to be motivated by political purposes (Charge I), and that he presided over two cases in which his personal attorney appeared (Charge II). Respondent filed a Verified Answer dated April 24, 2007. By Order dated April 27, 2007, the Commission designated Honorable Richard D. Simons as referee to hear and report proposed findings of fact and conclusions of law. A hearing was held on August 13, 14, 15 and 16 and December 5, 2007, in New York City. The referee filed a report on January 18,2008. -

CJA's September 2, 2005 Memo to D.A. Morgenthau

CnNrnnyo, JuntcrAl AccouNTABrLrry, rxc. P.O. Box 69, Gedney Station TeL (914)421-1200 E-Mail: judgewatch@olcom ,Yhite Plains, New York 10605-0069 Fax (914)428-4994 ll/eb site: wwwjudgewatch,org Elena Ruth Sassotoer,Coordinotor BY E-MAIL & FAX (8 pages) DATE: September2,2005 TO: MANHATTAN DISTRICT ATTORNEY ROBERT M. MORGENTHAU E-Mail: [email protected] Fax: 212-335-9394 WOULD-BE DISTzuCTATTORNEY LESLIE CROCKERSNYDER E-Mail: [email protected] Fax: 212-352-2290 FROM: Elena Ruth Sassower,Coordinator Centerfor Judicial Accountability,Inc. (CJA) RE: THE VOTERS' RIGHT TO YOUR RESPONSE Enclosedis the Centerfor JudicialAccountability's self-explanatory memo oftoday's dateto the mainstreampress - to which you areindicated recipients. Its title is: 'Examining Manhattan D.A. Morgenthau's Record with Respect to Judicial Comrption and Conflicts of Interest - and Getting His Responseand that of Would-BeD.A. Snyder". The voluminous substantiafingdocuments which we long ago provided to D.A. Morgenthau shouldhave been retained by his office -- andwe waive anyconfidentiality as he might invoketo obstructaccess to thosedocuments by the pressand public. For the benefit of Ms. Snyder,the immediately-salientdocuments are attachedto our e-mail transmittal. Hard copies will be promptly furnishedupon request. Thank you. fla*a4 cc: The mainstreampress Enclosure Cnxrrn 7o,JvntcrAl AccouNTABrLrry,rNc. P.O. Box 69, GedneyStation Tet. (914)421-1200 E-Mail: [email protected] IyhitePlains, New York 10605-0069 Fox (914)428-4994 lYebsite: wwwjudgewatch.org Elena Ruth Sassower,Coordinator BY E-MAIL & FAX (7 pages) DATE: September2,2005 TO: THE MAINSTREAM PRESS The New York Times New York Law Journal The Wall StreetJournal The New York Post New York DailyNews Newsday The New York Sun The New York Observer The New Yorker The Village Voice FROM: ElenaRuth Sassower,Coordinator Centerfor JudicialAccountability, Inc. -

Women in Crime Ink: Guest Michael Streed Talks About Sketchcop

11/26/2016 Women in Crime Ink: Guest Michael Streed talks about SketchCop 0 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In ABOUT WCI | FACEBOOK | KINDLE | WIKIPEDIA A B O U T U S T U E S D A Y , O C T O B E R 5 , 2 0 1 0 Guest Michael Streed talks about SketchCop "A blog worth reading" The Wall Street Journal by Andrea Campbell There is so much involved WRITING TODAY with being a forensic artist and it is a small community. Today we have an interview G U E S T C O N T R I B U T O R O R D E R B O O K S B Y W C I with Michael Streed, artist C O N T R I B U T O R S extraordinaire. Q.: Michael, thank you for being my interview guest. Can you tell WCI readers something about your background? Adobe Flash M.: I began my career as a Player is out of ‘street cop’ and retired 31 date. years later as “The SketchCop.” During that time, I worked several investigative assignments that helped me learn a lot about eyewitnesses. It also helped hone my interviewing skills. Shortly after becoming a police officer, I trained as a police composite artist with the WOMEN IN CRIME INK Los Angeles Police Department. My career as a forensic artist CONTRIBUTORS paralleled my work as a police officer and took me throughout the Search country to train with the best forensic artists of that era. I blended my forensic art training with college courses in life drawing and was H O L L Y H U G H E S Custom Search privileged to become trusted to work on some of the country’s worst cases including the torture murder of a DEA agent in Mexico, The C O D E A M B E R A L E R T Baton Rouge Serial Killer, The Samantha Runnion Abduction/Murder and the Anthony Martinez Abduction/Murder.