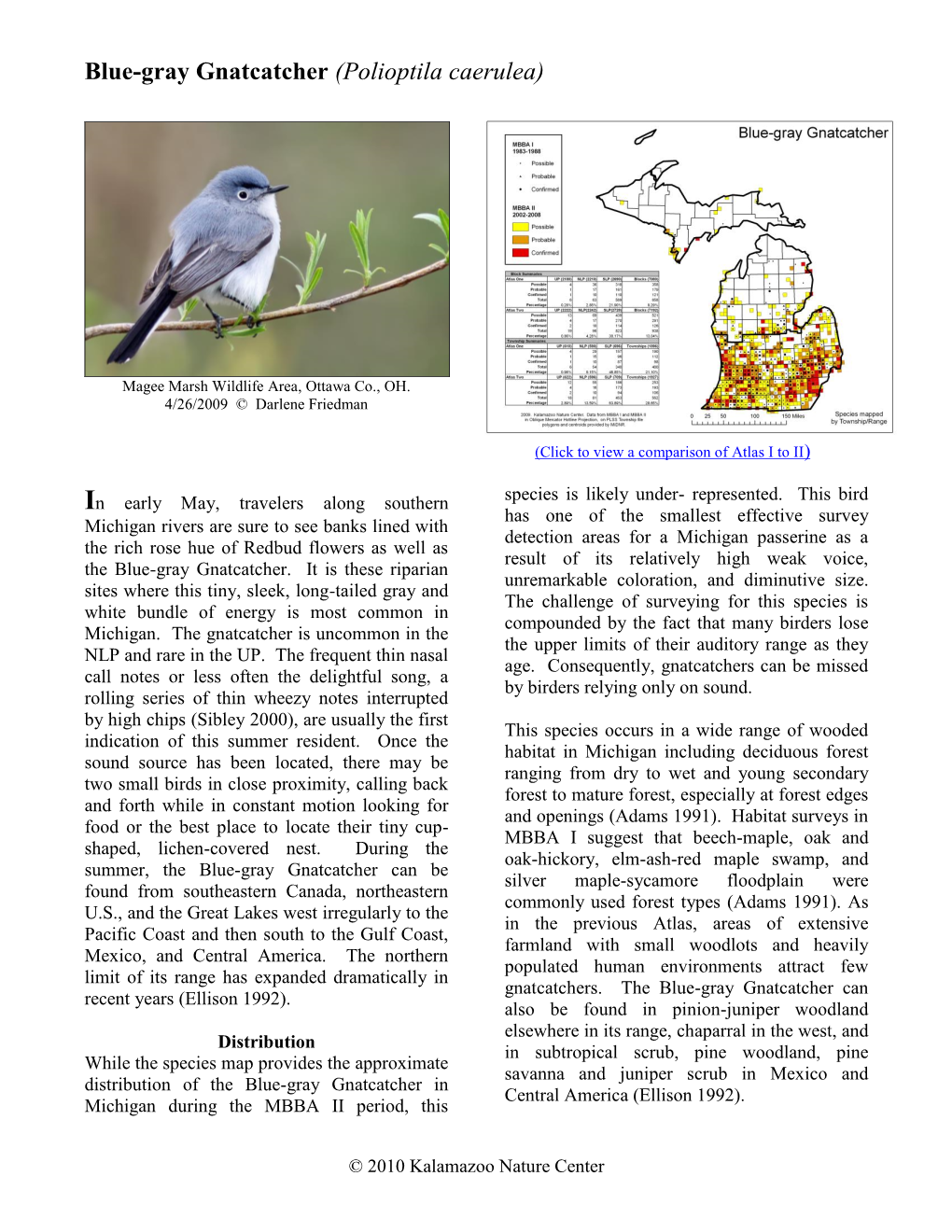

Blue-Gray Gnatcatcher (Polioptila Caerulea)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blue-Gray Gnatcatcher

Blue-gray Gnatcatcher Polioptila caerulea Taxa: Avian SE-GAP Spp Code: bBGGN Order: Passeriformes ITIS Species Code: 179853 Family: Sylviidae NatureServe Element Code: ABPBJ08010 KNOWN RANGE: PREDICTED HABITAT: P:\Proj1\SEGap P:\Proj1\SEGap Range Map Link: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/maps/SE_Range_bBGGN.pdf Predicted Habitat Map Link: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/maps/SE_Dist_bBGGN.pdf GAP Online Tool Link: http://www.gapserve.ncsu.edu/segap/segap/index2.php?species=bBGGN Data Download: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/region/vert/bBGGN_se00.zip PROTECTION STATUS: Reported on March 14, 2011 Federal Status: --- State Status: ID (P), KY (N), NJ (INC/S), NV (YES), NY (PB), RI (Not Listed), UT (None), UT (None), BC (8 (2005)), QC (Non suivie) NS Global Rank: G5 NS State Rank: AL (S5B,S3N), AR (S5B), AZ (S5), CA (S4), CO (S5B), CO (S5B), CT (S5B), CT (S5B), DC (S3B,S3N), DE (S5B), FL (SNRB,SNRN), GA (S5), IA (S4B,S4N), ID (S3?), IL (S5), IN (S4B), KS (S4B), KY (S5B), LA (S3N,S4B), MA (S4B), MD (S5B), ME (S2S3), MI (S5), MN (SNRB), MO (SNRB), MS (S5B), MS (S5B), MT (S1B), NC (S5B,S2N), NE (S4), NH (S4B), NJ (S4B), NM (S4B,S4N), NV (S4B), NY (S5), OH (S5), OK (S5B), OR (S3B), PA (S5B), RI (S4B), SC (SNRB,SNRN), SD (S1B), SD (S1B), TN (S5), TX (S3B), UT (S5B), UT (S5B), VA (S5), VT (S3B), VT (S3B), WA (SNA), WI (S4B), WI (S4B), WV (S5B), WY (S3?B), WY (S3?B), AB (SNA), BC (SNA), LB (SNA), MB (SNA), NB (SNA), NF (SNA), NS (SNA), ON (S4B), PE (SNA), QC (S4B), SK (SNA) bBGGN Page 1 of 6 SUMMARY OF PREDICTED HABITAT BY MANAGMENT AND GAP PROTECTION STATUS: US FWS US Forest Service Tenn. -

Common Birds of the Prescott Area Nuthatch.Cdr

Birds are listed by their typical habitats. Coniferous Forest Riparian (Creekside) Woodland (Some species may be found in more Sharp-shinned Hawk (w) Anna's Hummingbird (s) than one habitat.) Cooper's Hawk Black-chinned Hummingbird (s) (w) = winter (s) = summer Broad-tailed Hummingbird (s) Rufous Hummingbird (s) Acorn Woodpecker Black Phoebe Pinyon/Juniper/Oak Woodland Red-naped Sapsucker (w) Plumbeous Vireo (s) and Chaparral Hairy Woodpecker Warbling Vireo (s) Gambel's Quail . Western Wood-Pewee (s) House Wren (s) Ash-throated Flycatcher (s) Cordilleran Flycatcher (s) Lucy's Warbler (s) Western Scrub-Jay Hutton's Vireo Yellow Warbler (s) Bridled Titmouse Steller's Jay Summer Tanager (s) Juniper Titmouse . Mountain Chickadee Song Sparrow (w) Bushtit White-breasted Nuthatch Lincoln's Sparrow (w) Bewick's Wren . Pygmy Nuthatch Blue Grosbeak (s) Ruby-crowned Kinglet (w) Brown Creeper Brown-headed Cowbird (s) Blue-gray Gnatcatcher (s) Western Bluebird Bullock's Oriole (s) Crissal Thrasher Hermit Thrush Lesser Goldfinch Phainopepla (s) Yellow-rumped Warbler (w) Lake and Marsh Virginia's Warbler (s) Grace's Warbler (s) Black-throated Gray Warbler (s) Red-faced Warbler (s) Pied-billed Grebe Spotted Towhee Painted Redstart (s) Eared Grebe (w) Canyon Towhee Hepatic Tanager (s) Double-crested Cormorant Rufous-crowned Sparrow Western Tanager (s) Great Blue Heron White-crowned Sparrow (w) Chipping Sparrow Gadwall (w) Black-headed Grosbeak (s) Dark-eyed Junco (w) American Wigeon (w) Scott’s Oriole (s) Pine Siskin Mallard Lake and Marsh (cont.) Varied or Other Habitats Cinnamon Teal (s) Turkey Vulture (s) Common Birds Northern Shoveler (w) Red-tailed Hawk Northern Pintail (w) Rock Pigeon of the Green-winged Teal (w) Eurasian Collared-Dove Prescott Canvasback (w) Mourning Dove Ring-necked Duck (w) Greater Roadrunner Area Lesser Scaup (w) Ladder-backed Woodpecker Bufflehead (w) Northern Flicker Common Merganser (w) Cassin's Kingbird (s) Ruddy Duck (w) Common Raven American Coot Violet-green Swallow (s) . -

Biological Resources Core Area

Sweetwater Reservoir/ San Miguel Mountains/ Sweetwater River BRCA 94 Jamul Mountains BRCA eArea.mxd Mountains/Marron Valley BRCA Project Area Proposed Proctor Valley Road Alignment Otay Lakes/Otay Mesa/ Otay Ranch RMP Preserve, Conserved Open Space and Non-Impacted LDA Otay River Valley BRCA Cores Linkages 0 1,700 3,400 Feet SOURCE: USGS 7.5-minute Topographic Map; Hunsaker 2017; SANGIS 2016 FIGURE 3-3 Biological Resources Core Area Otay Ranch Village 14 and Planning Areas 16/19 - Preserve Status Report NOTE: See Figure 6-2 for Corridor and Habitat Linkages Post Exchange and Boundary Line Adjustment Date: 2/8/2018 - Last saved by: mmcginnis - Path: Z:\Projects\j820701\MAPDOC\DOCUMENT\BTR\PreserveAppendix\Figure3_3_BioCor - Path: mmcginnis by: saved Last - 2/8/2018 Date: Otay Ranch Village 14 and Planning Areas 16/19 Otay Ranch RMP Preserve Status Report INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK 8207 122 February 2018 L4 R1 L4 R1 94 L3 L3 R1 L4 PRESUMPTIVE CORRIDOR Project Area R1 Proposed Proctor Valley Road Alignment Otay Ranch RMP Preserve, Conserved Open Space and Non-Impacted LDA Otay Ranch Village 13 L3 Public Lands CDFW Owned Land L3 K R E Wildlife Crossings Z U A R1 L E Upper R7 U R D C Proctor Valley Land Use Otay Project Applicant Otay Ranch Development Reservoir R7 Project Applicant Otay Ranch Preserve feCorridors.mxd Existing Wildlife Corridors Major Local Corridor for Focal Mammal and Bird Species Regional Corridor for Focal Mammal and Bird Species R2 R10 Public Lands R2 BLM R2 CDFW R10 DOD USFWS R11 R2 R8 0 1,700 3,400 Lower Otay Reservoir -

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with Birds Observed Off-Campus During BIOL3400 Field Course

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with birds observed off-campus during BIOL3400 Field course Photo Credit: Talton Cooper Species Descriptions and Photos by students of BIOL3400 Edited by Troy A. Ladine Photo Credit: Kenneth Anding Links to Tables, Figures, and Species accounts for birds observed during May-term course or winter bird counts. Figure 1. Location of Environmental Studies Area Table. 1. Number of species and number of days observing birds during the field course from 2005 to 2016 and annual statistics. Table 2. Compilation of species observed during May 2005 - 2016 on campus and off-campus. Table 3. Number of days, by year, species have been observed on the campus of ETBU. Table 4. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during the off-campus trips. Table 5. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during a winter count of birds on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Table 6. Species observed from 1 September to 1 October 2009 on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Alphabetical Listing of Birds with authors of accounts and photographers . A Acadian Flycatcher B Anhinga B Belted Kingfisher Alder Flycatcher Bald Eagle Travis W. Sammons American Bittern Shane Kelehan Bewick's Wren Lynlea Hansen Rusty Collier Black Phoebe American Coot Leslie Fletcher Black-throated Blue Warbler Jordan Bartlett Jovana Nieto Jacob Stone American Crow Baltimore Oriole Black Vulture Zane Gruznina Pete Fitzsimmons Jeremy Alexander Darius Roberts George Plumlee Blair Brown Rachel Hastie Janae Wineland Brent Lewis American Goldfinch Barn Swallow Keely Schlabs Kathleen Santanello Katy Gifford Black-and-white Warbler Matthew Armendarez Jordan Brewer Sheridan A. -

Black-Capped Gnatcatcher, a New Breeding Bird for the United States; with a Key to the North American Species of Polioptila

THE AUK A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ORNITHOLOGY VOL. 90 AvmL 1973 No. 2 BLACK-CAPPED GNATCATCHER, A NEW BREEDING BIRD FOR THE UNITED STATES; WITH A KEY TO THE NORTH AMERICAN SPECIES OF POLIOPTILA ALLAN R. PHILLIPS,STEVEN SPEICI-I, AND WILLIAM HARRISON ON 22 June 1971 one of us (S.S.) collecteda family of five gnat- catchers,including three fledglings,along Sonoita Creek, 8.5 km north- east of Nogales, Santa Cruz County, Arizona. The adults, male and female, were later determinedon careful comparisonto be Black-capped Gnatcatchers(Polioptila nigriceps), an endemicspecies of northwestern Mexico never previously recorded in the United States. Hitherto the northernmostrecords had been east-southeastof Hermosillo, Sonora (van Rossem,1945) and near Ures, northeastof Hermosillo (Phillips, 1962), localitiesapproximately 240 and 210 km, respectively,south of Nogales. Thenceit rangessouth to Colima. Friedmann (1957) recognizedtwo races,restricta Brewsterof Sonora and adjacent Chihuahua and nominate nigricepsBaird of Sinaloa and Durango to Colima; these he regarded,however, as subspeciesof the more southeasternP. albiloris--a treatment with which we cannot agree (see below). Brewster'sname refers presumablyto the more restricted black capsof his Sonoramales, which howeverwere taken in late winter and probably had not completed the prealternate (prenuptial) molt; whereasBaird's type was in worn summerplumage. Though this char- acter has been generallyrecognized, no differencein the extent of black, accordingto geographicarea, is obviousto us. There is, however,a cline of increasingsize, best marked in tail length, northward; on this basis birdsof northernSinaloa are nearestrestricta, though somewhat variable, and all Sonorabirds are restricta. The Arizona pair, thoughworn, are of maximumdimensions: wing (chord) 49.8 mm in the male (48.1 in female); tail 55.6 (54.5 in female, despite the loss of the central pair of rectrices). -

Coastal Cactus Wren & California Gnatcatcher Habitat Restoration Project

Coastal Cactus Wren & California Gnatcatcher Habitat Restoration Project Encanto and Radio Canyons San Diego, CA Final Report AECOM and GROUNDWORK SAN DIEGO-CHOLLAS CREEK for SANDAG April 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................................... 1 PRE-IMPLEMENTATION ................................................................................................................................. 2 Project Boundary Definition ................................................................................................................ 2 Vegetation Mapping and Species Inventory ....................................................................................... 2 Coastal Cactus Wren and California Gnatcatcher Surveys .................................................................. 8 Cholla Harvesting .............................................................................................................................. 11 Plant Nursery Site Selection and Preparation ................................................................................... 12 Cholla Propagation ............................................................................................................................ 12 ON-SITE IMPLEMENTATION ........................................................................................................................ 12 Site Preparation................................................................................................................................ -

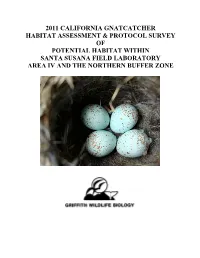

2011 California Gnatcatcher Habitat Assessment & Protocol Survey

2011 CALIFORNIA GNATCATCHER HABITAT ASSESSMENT & PROTOCOL SURVEY OF POTENTIAL HABITAT WITHIN SANTA SUSANA FIELD LABORATORY AREA IV AND THE NORTHERN BUFFER ZONE 2011 California Gnatcatcher Habitat Assessment and Protocol Survey of 2 Potential Habitat Within Santa Susana Field Laboratory Area IV and Northern Buffer Zone 2011 CALIFORNIA GNATCATCHER HABITAT ASSESSMENT & PROTOCOL SURVEY OF POTENTIAL HABITAT WITHIN SANTA SUSANA FIELD LABORATORY AREA IV AND THE NORTHERN BUFFER ZONE prepared for: Envicom Corporation Attn: Travis Cullen 28328 Agoura Road Agoura Hills, CA 91301 (818) 879-4700 ext.233 www.envicomcorporation.com prepared by: Griffith Wildlife Biology John T. Griffith 22670 Hwy M-203 P.O. Box 47 Calumet, Michigan 49913 (906) 337-0782 www.griffithwildlife.com Final Letter Report 6 July 2011 2011 California Gnatcatcher Habitat Assessment and Protocol Survey of iii Potential Habitat Within Santa Susana Field Laboratory Area IV and Northern Buffer Zone EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Santa Susana Field Laboratory in southeastern Ventura County, California, contains coastal sage scrub habitat of the type preferred by the federally threatened Coastal California gnatcatcher (Polioptila californica ssp. californica). As indicated in Figure 1 of the Biological Opinion for the Santa Susana Field Laboratory Area IV Radiological Survey issued by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, approximately 151 acres in Area IV and the contiguous undeveloped Northern Buffer Zone (NBZ) to the north and west were identified as potentially suitable habitat for the gnatcatcher. A habitat reconnaissance survey was subsequently conducted in areas initially identified as suitable habitat. During this reconnaissance, direct field observation determined that less than 100 of the 151 acres were suitable gnatcatcher habitat. -

Wildland Fire in Ecosystems: Effects of Fire on Fauna

United States Department of Agriculture Wildland Fire in Forest Service Rocky Mountain Ecosystems Research Station General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-42- volume 1 Effects of Fire on Fauna January 2000 Abstract _____________________________________ Smith, Jane Kapler, ed. 2000. Wildland fire in ecosystems: effects of fire on fauna. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 1. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 83 p. Fires affect animals mainly through effects on their habitat. Fires often cause short-term increases in wildlife foods that contribute to increases in populations of some animals. These increases are moderated by the animals’ ability to thrive in the altered, often simplified, structure of the postfire environment. The extent of fire effects on animal communities generally depends on the extent of change in habitat structure and species composition caused by fire. Stand-replacement fires usually cause greater changes in the faunal communities of forests than in those of grasslands. Within forests, stand- replacement fires usually alter the animal community more dramatically than understory fires. Animal species are adapted to survive the pattern of fire frequency, season, size, severity, and uniformity that characterized their habitat in presettlement times. When fire frequency increases or decreases substantially or fire severity changes from presettlement patterns, habitat for many animal species declines. Keywords: fire effects, fire management, fire regime, habitat, succession, wildlife The volumes in “The Rainbow Series” will be published during the year 2000. To order, check the box or boxes below, fill in the address form, and send to the mailing address listed below. -

Coastal California Gnatcatcher (Polioptila Californica Californica)

Coastal California Gnatcatcher (Polioptila californica californica) 5-year Review: Summary and Evaluation Coastal California gnatcatcher (Polioptila californica californica) and habitat. Photo credit Marci Koski and Gjon Hazard (USFWS). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Carlsbad Fish and Wildlife Office Carlsbad, California September 29, 2010 2010 Coastal California Gnatcatcher 5-year Review 5-YEAR REVIEW coastal California gnatcatcher (Polioptila californica californica) I. GENERAL INFORMATION Purpose of 5-year Reviews: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) is required by section 4(c)(2) of the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended (Act), to conduct a review of each listed species at least once every 5 years. The purpose of a 5-year review is to evaluate the status of the species since it was listed or since the most recent 5-year review. Based on the 5-year review, we recommend whether the species should be removed from the list of endangered and threatened species (delisted), be changed in status from endangered to threatened (downlisted), or be changed in status from threatened to endangered (uplisted). Our original listing of a species as endangered or threatened is based on the existence of threats attributable to one or more of the five threat factors described in section 4(a)(1) of the Act, and we must consider these same five factors in any subsequent consideration of reclassification or delisting of a species. In the 5-year review, we consider the best available scientific and commercial data on the species, and focus on new information available since the species was listed or last reviewed. -

American Ornithologists' Union

m eeting PrOgrAm 129th Stated Meeting of the AmericAn OrnithOlOgists’ UniOn 24-29 July, 2011 hyatt Regency JackSonville RiveRfRont JackSonville, floRida, uSa Co-hosted by the University of Florida and the Florida Ornithological Society. Jacksonville, florida a merican ornithologists’ union Co ntents Ogi r An Zers .................................................................................................................................................................................2 meeting hOsts ...........................................................................................................................................................................2 registrAtiOn AnD generAl inFOrmAtiOn ............................................................................................................................3 Registration/information desk .................................................................................................................................................................................................3 Message/job board .....................................................................................................................................................................................................................3 Parking ..........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................3 Internet, fax, -

Pine Warbler (Dendroica Pinus)

Management Indicator Species for the New Plan Success in maintaining and restoring composition, structure, and function of forest ecosystems within desired ranges of variability is reflected by both changes in forest condition and by levels of management and other effects that are shaping these communities. Monitoring will include tracking the abundance of major forest cover/community types and levels of management activities conducted to maintain and restore desired conditions. Population trends and habitats of Management Indicator Species will be monitored to help indicate effects of national forest management within selected communities. Indicator: Pine Warbler (Dendroica pinus) From USGS Patuxent Bird ID InfoCenter Reasons for Selection: The pine warbler is closely associated with pine and pine-oak forests, generally occurring only where some pine component is present. It therefore is an appropriate indicator of the effects of management in restoring and maintaining pine forests. Ecology & Life History Basic Description: A 14-cm-long bird (warbler). General Description: Slightly larger than most other wood warblers (13-14 cm length, 9.4-15.1 g). Adult males have un-streaked, olive-green upper parts, a yellow throat and breast with indistinct black streaking on sides of the breast, a white belly and under tail coverts, dark wings with faint bluish tinge, and two broad whitish wing-bars. Adult females are duller and variable, but always with browner or grayer upper parts, a paler yellow throat and breast, duller white belly and under tail coverts. Bill is black and relatively heavy for a warbler. Immature is like adult female, but brownish gray above, breast, belly, and under tail coverts are washed with buff. -

Featured Photo Has the Black-Capped Gnatcatcher Occurred in Baja California Sur? Steven G

FEATURED PHOTO HAS THE BLACK-CAPPED GNATCATCHER OCCURRED IN BAJA CALIFORNIA SUR? STEVEN G. MLODINOW, 1522 Venice Lane, Longmont, Colorado 80503; [email protected] On 7 November 2011, Daniel Galindo and I were walking along the west side of the pond at Posada La Poza in Todos Santos, Baja California Sur. It was about 90 minutes before sunset, and passerines were quite active. In an area of dense low scrub bordering the beach, we encountered a mixed foraging flock consisting largely of Blue-gray Gnatcatchers (Polioptila caerulea). From the flock, we heard several times a thin mewing call reminiscent of the California Gnatcatcher (P. californica). Eager to photograph California Gnatcatchers, I pursued what I thought was the call- ing bird, taking several high-quality photographs before the flock dispersed into the surrounding countryside. Later examination of the photographs revealed a gnatcatcher with extensively pale undersides to the rectrices, as seen in the Blue-gray Gnatcatcher and Black-capped Gnatcatcher (P. nigriceps) but not the California Gnatcatcher. The bird I photo- graphed, however, had a number of marks less consistent with the Blue-gray and more consistent with the Black-capped (see this issue’s back cover), a species unrecorded and unexpected on the Baja California peninsula. This photograph shows most of the important features that suggest the Black-capped: tail morphology, narrow and nearly broken eye-ring, and a large bill. The most intriguing mark is the tail structure. Easily visible is a large gap between r5 and r6 (the shortest visible rectrix and the next shortest), which is typical of the Black-capped Gnatcatcher but not of any other gnatcatcher occurring in the United States or northwestern Mexico (Dunn and Garrett 1987, Pyle 1997, Sibley 2000).