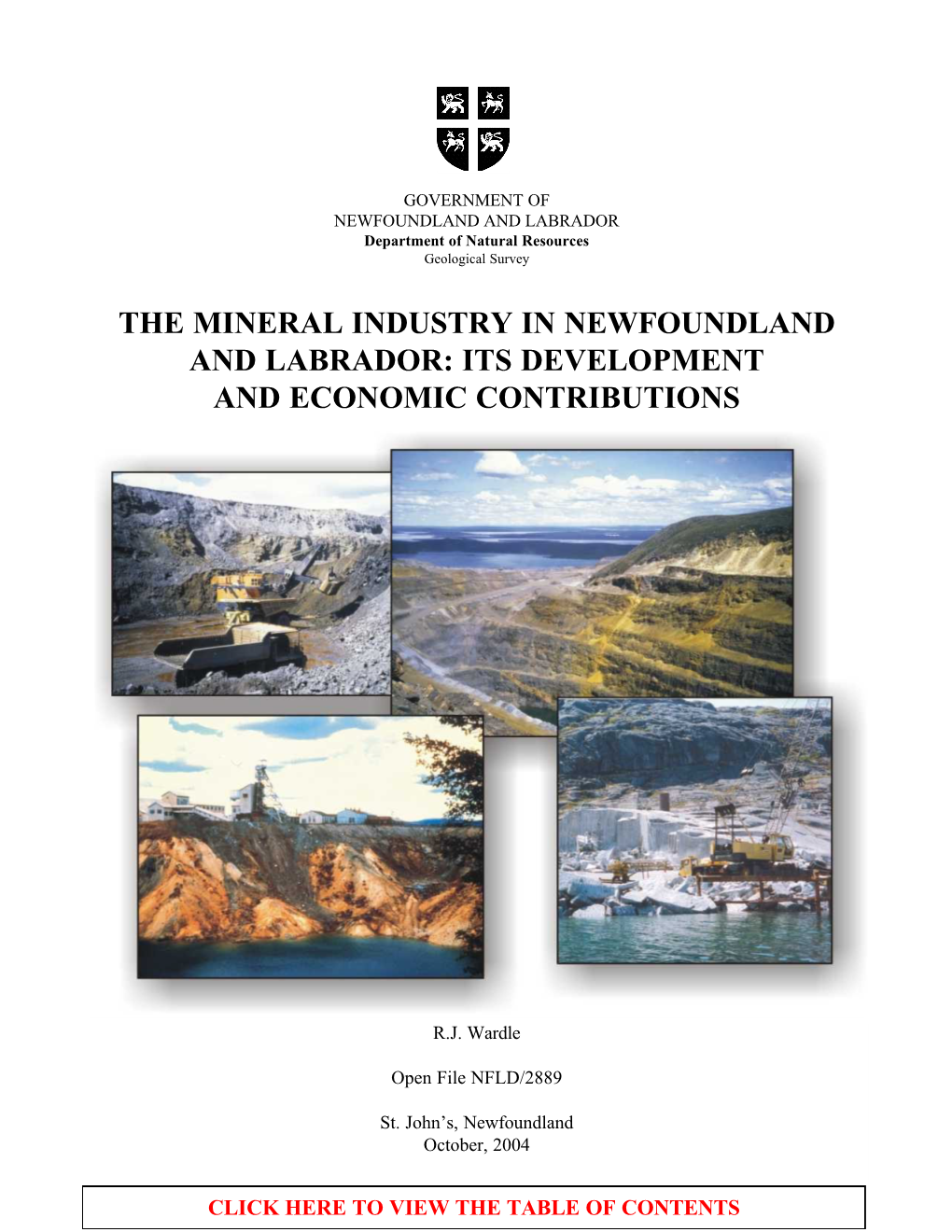

The Mineral Industry in Newfoundland and Labrador: Its Development and Economic Contributions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

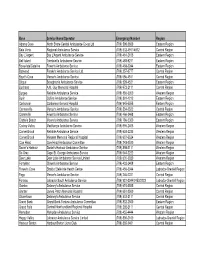

Revised Emergency Contact #S for Road Ambulance Operators

Base Service Name/Operator Emergency Number Region Adams Cove North Shore Central Ambulance Co-op Ltd (709) 598-2600 Eastern Region Baie Verte Regional Ambulance Service (709) 532-4911/4912 Central Region Bay L'Argent Bay L'Argent Ambulance Service (709) 461-2105 Eastern Region Bell Island Tremblett's Ambulance Service (709) 488-9211 Eastern Region Bonavista/Catalina Fewer's Ambulance Service (709) 468-2244 Eastern Region Botwood Freake's Ambulance Service Ltd. (709) 257-3777 Central Region Boyd's Cove Mercer's Ambulance Service (709) 656-4511 Central Region Brigus Broughton's Ambulance Service (709) 528-4521 Eastern Region Buchans A.M. Guy Memorial Hospital (709) 672-2111 Central Region Burgeo Reliable Ambulance Service (709) 886-3350 Western Region Burin Collins Ambulance Service (709) 891-1212 Eastern Region Carbonear Carbonear General Hospital (709) 945-5555 Eastern Region Carmanville Mercer's Ambulance Service (709) 534-2522 Central Region Clarenville Fewer's Ambulance Service (709) 466-3468 Eastern Region Clarke's Beach Moore's Ambulance Service (709) 786-5300 Eastern Region Codroy Valley MacKenzie Ambulance Service (709) 695-2405 Western Region Corner Brook Reliable Ambulance Service (709) 634-2235 Western Region Corner Brook Western Memorial Regional Hospital (709) 637-5524 Western Region Cow Head Cow Head Ambulance Committee (709) 243-2520 Western Region Daniel's Harbour Daniel's Harbour Ambulance Service (709) 898-2111 Western Region De Grau Cape St. George Ambulance Service (709) 644-2222 Western Region Deer Lake Deer Lake Ambulance -

The Newfoundland and Labrador Gazette

No Subordinate Legislation received at time of printing THE NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR GAZETTE PART I PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY Vol. 84 ST. JOHN’S, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 23, 2009 No. 43 EMBALMERS AND FUNERAL DIRECTORS ACT, 2008 NOTICE The following is a list of names and addresses of Funeral Homes 2009 to whom licences and permits have been issued under the Embalmers and Funeral Directors Act, cE-7.1, SNL2008 as amended. Name Street 1 City Province Postal Code Barrett's Funeral Home Mt. Pearl 328 Hamilton Avenue St. John's NL A1E 1J9 Barrett's Funeral Home St. John's 328 Hamilton Avenue St. John's NL A1E 1J9 Blundon's Funeral Home-Clarenville 8 Harbour Drive Clarenville NL A5A 4H6 Botwood Funeral Home 147 Commonwealth Drive Botwood NL A0H 1E0 Broughton's Funeral Home P. O. Box 14 Brigus NL A0A 1K0 Burin Funeral Home 2 Wilson Avenue Clarenville NL A5A 2B6 Carnell's Funeral Home Ltd. P. O. Box 8567 St. John's NL A1B 3P2 Caul's Funeral Home St. John's P. O. Box 2117 St. John's NL A1C 5R6 Caul's Funeral Home Torbay P. O. Box 2117 St. John's NL A1C 5R6 Central Funeral Home--B. Falls 45 Union Street Gr. Falls--Windsor NL A2A 2C9 Central Funeral Home--GF/Windsor 45 Union Street Gr. Falls--Windsor NL A2A 2C9 Central Funeral Home--Springdale 45 Union Street Gr. Falls--Windsor NL A2A 2C9 Conway's Funeral Home P. O. Box 309 Holyrood NL A0A 2R0 Coomb's Funeral Home P. O. Box 267 Placentia NL A0B 2Y0 Country Haven Funeral Home 167 Country Road Corner Brook NL A2H 4M5 Don Gibbons Ltd. -

Canadian Money Word Search Extension Activity for Earn, Spend, Save & Share, I Need It! I Want It! Or Spending Sense Presentations

Canadian Money Word Search Extension Activity for Earn, Spend, Save & Share, I Need It! I Want It! or Spending Sense Presentations Grade Level: Grades 1-3 Learning Objective: This extension activity, along with the Earn, Spend, Save & Share, I Need It! I Want It! or Spending Sense presentations should help students: • learn common money terms • develop their visual ability for recognizing words related to money Materials Needed: • Canadian Money Word Search & pencil (1 per student) Preparation: 1. Review the meanings of the money words found in the worksheet: dollar: a unit of money equal to 100 cents bill: paper money which is also called notes. Bills represent larger amounts of money than coins. Canadian bills are produced at the bank of Canada located in Ottawa, Ontario nickel: a coin worth five cents loonie: a coin worth 100 cents/one dollar twenty: a number equal in dollar value to a green Canadian bill ($20 bill). Twenty dollars can also be represented by several combinations of bills and coins of smaller value coin: round pieces of metal used as money. Canada has five coins (nickel, dime, quarter, loonie, toonie). Coins represent smaller values of money than bills. Canadian coins are produced at the royal Canadian mint located in Winnipeg, Manitoba dime: a coin worth ten cents toonie: a coin worth 200 cents/ two dollars fifty: a number equal in dollar value to a red Canadian bill ($50 bill). Fifty dollars can also be represented by a several combinations of bills and coins of smaller value quarter: a coin worth twenty-five cents ten: a number equal in dollar value to a purple Canadian bill ($10 bill). -

NEWFOUNDLAND and LABRADOR COLLEGE of OPTOMETRISTS Box 23085, Churchill Park, St

NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR COLLEGE OF OPTOMETRISTS Box 23085, Churchill Park, St. John's, NL A1B 4J9 Following are the names of Optometrists registered with the Newfoundland and Labrador College of Optometrists as of 1 January 2014 who hold a therapeutic drug certificate and may prescribe a limited number of medications as outlined in the following regulation: http://www.assembly.nl.ca/Legislation/sr/Regulations/rc120090.htm#3_ DR. ALPHONSUS A. BALLARD, GRAND FALLS-WINDSOR, NL DR. JONATHAN BENSE, ST. JOHN’S, NL DR. GARRY C. BEST, GANDER, NL DR. JUSTIN BOULAY, ST. JOHN’S, NL DR. LUC F. BOULAY, ST. JOHN'S, NL DR. RICHARD A. BUCHANAN, SPRINGDALE, NL DR. ALISON CAIGER-WATSON, GRAND FALLS-WINDSOR, NL DR. JOHN M. CASHIN, ST. JOHN’S, NL DR. GEORGE COLBOURNE, CORNER BROOK, NL DR. DOUGLAS COTE, PORT AUX BASQUES, NL DR. CECIL J. DUNCAN, GRAND FALLS-WINDSOR, NL DR. CARL DURAND, CORNER BROOK, NL DR. RACHEL GARDINER, GOULDS, NL DR. CLARE HALLERAN, CLARENVILLE, NL DR. DEAN P. HALLERAN, CLARENVILLE, NL DR. DEBORA HALLERAN, CLARENVILLE, NL DR. KEVIN HALLERAN, MOUNT PEARL, NL DR. ELSIE K. HARRIS, STEPHENVILLE, NL DR. JESSICA HEAD, GRAND FALLS-WINDSOR, NL 1 of 3 DR. IAN HENDERSON, ST. JOHN'S, NL DR. PAUL HISCOCK, ST. JOHN'S, NL DR. LISA HOUNSELL, ST. JOHN’S, NL DR. RICHARD J. HOWLETT, GRAND FALLS-WINDSOR, NL DR. SARAH HUTCHENS, ST. JOHN’S, NL DR. GRACE HWANG, GRAND FALLS-WINDSOR, NL DR. PATRICK KEAN, BAY ROBERTS, NL DR. NADINE KIELLEY, ST. JOHN’S, NL DR. CHRISTIE LAW, ST. JOHN’S, NL DR. ANGELA MacDONALD, SYDNEY, NS DR. -

The Hitch-Hiker Is Intended to Provide Information Which Beginning Adult Readers Can Read and Understand

CONTENTS: Foreword Acknowledgements Chapter 1: The Southwestern Corner Chapter 2: The Great Northern Peninsula Chapter 3: Labrador Chapter 4: Deer Lake to Bishop's Falls Chapter 5: Botwood to Twillingate Chapter 6: Glenwood to Gambo Chapter 7: Glovertown to Bonavista Chapter 8: The South Coast Chapter 9: Goobies to Cape St. Mary's to Whitbourne Chapter 10: Trinity-Conception Chapter 11: St. John's and the Eastern Avalon FOREWORD This book was written to give students a closer look at Newfoundland and Labrador. Learning about our own part of the earth can help us get a better understanding of the world at large. Much of the information now available about our province is aimed at young readers and people with at least a high school education. The Hitch-Hiker is intended to provide information which beginning adult readers can read and understand. This work has a special feature we hope readers will appreciate and enjoy. Many of the places written about in this book are seen through the eyes of an adult learner and other fictional characters. These characters were created to help add a touch of reality to the printed page. We hope the characters and the things they learn and talk about also give the reader a better understanding of our province. Above all, we hope this book challenges your curiosity and encourages you to search for more information about our land. Don McDonald Director of Programs and Services Newfoundland and Labrador Literacy Development Council ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank the many people who so kindly and eagerly helped me during the production of this book. -

Iiiiiiiiiiitoilf911)118Iiiiiii

iiiiiiiiiiitoilf911)1118iiiiiii ERRATUM Activities of the Resource Development Branch Newfoundland Region March - September, 1974 p 16. fifth line from bottom of page should read Four of these were tagged in 1971, , four salmon were recaptured on the south coast of Insular Newfound- land; one was recaptured in Salmonier Arm, Rex Porter Activities of the Resource Development Branch Newfoundland Region January-February, 1974 , On Friday, March 1, 1974, the Branch Executive met at 3:00 p.m. Attending were V.R. Taylor, B.R. Bauld, R.J. Wiseman, W.J. Walsh, J. D. Pratt, L.G. Riche, and C.A. Whalen. General: Discussion of the 1974-75 budget took up almost all the meeting time. Generally speaking, the Branch budget for 1974-75 is not substantially greater than that of the past fiscal year. The general concensus expressed was that some "belt-tightening" would be required by all Groups if we are to keep our operations within budgetory limits. Meetings! On January 3, 1974 an informal meeting was held in Building 302 between representatives of the Branch and H. Lear and R. Payne of the St. John's Biological Station to discuss the agenda and format of the forthcoming Program Working Party on Atlantic Anadromous Fish to be tentatively held during April 23-25 in St. John's. Representing the Branch were V.R. Taylor, J.D. Pratt, R.J. Wiseman, and D. Waldron. R.J. Wiseman, C.A. Whalen, M. Farwell, and L. Coady of the Branch attended the 27th Annual Meeting of the C.C.F.F.R. held in Ottawa during January 7-8, 1974. -

Labrador City and Wabush : Resilient Communities Karen Oldford - Mayor Town of Labrador City Ken Anthony – CAO Town of Wabush

Labrador City and Wabush : Resilient Communities Karen Oldford - Mayor Town of Labrador City Ken Anthony – CAO Town of Wabush Benefits of Labrador West Established community = reduced start up costs for industry Suited for operation phase of projects Experience of labour force Resource companies share in the value of creating community through corporate stewardship. Community amenities key for retaining workers. Link to natural environment – recreation amenities. Boom Bust Cycle Last big Bust 1982 Hundreds of homes vacant for approx 8 yrs Homes sold by banks and companies for $5,000- $25,000 Affordable homes and affordable apartment rents until 2005 2010 – same homes sell for $325,000 - $549,000 rental rates now $1,000 per bedroom i.e. 1 bedroom apt 1,200, 2 bedroom $2,000 and house rental $5,000 month! Challenges of Labrador West • Economic dependence on single industry • Growth impaired due to subsurface mineral rights • Transient Workforce Population • Expense of building/operating in remote northern location Challenges: Single Industry Market is volatile Community grows and diminishes in response to the resource Non renewable = finite. Challenges: Growth • Expansion/development encroach on mineral reserves • Land management strongly influenced by Provincial interest and local industry • Growth responds to market conditions – often lags behind needs of community and industry Challenges: Flyin/Flyout Arrangements Necessary for resource projects when workforce needs are high but short lived. I.e. construction phase Transient residents – not fully engaged in community (i.e. lack of community involvement and volunteerism. Often project negative image of the region due to their lived reality.) Negative perception amongst long-term residents of “contractors”. -

Carol Inn Listing Flyer.Indd

HOTEL INVESTMENT PROPERTY CAROL INN 215 Drake Avenue, Labrador City, NL HOTEL ACQUISITION OPPORTUNITY CBRE, as the exclusive advisor to PwC, is pleased to present for sale the Carol Inn (the “Hotel” or “Property”). ROB COLEMAN +1 709 754 1454 Offi ce The Carol Inn is located within the Central Business District of Labrador City with high visibility via Drake Avenue. The hotel is +1 709 693 3868 Cell approximately 4.7 kilometers north of the Wabush Airport. [email protected] Strategically located within Lab West, the property features visibilty from the Trans-Labrador Highway, allowing for easy access to all high LLOYD NASH volume roads within the community. +1 709 754 0082 Offi ce +1 709 699 7508 Cell The Hotel has a total of 22 guest rooms, offering a mix of room types to meet leisure, corporate, and extended-stay demand. Signifi cant [email protected] rennovations have been undertaken in recent years to the hotel. The Property also contains basement meeting rooms, main level bar, 140 Water Street, Suite 705 dining room and restaurant. Oppotunities exist for redevelopment, of St. John`s, NL A1C 6H6 those areas currently not in operation. Fax +1 709 754 1455 This property has abundant parking and the potential for expansion. This unique opportunity rarely comes to market in Lab West - a rare commercial building, strategically located in the heart of Lab West. HOTEL ACQUISITION OPPORTUNITY INVESTMENT PROFILE | CAROL INN INVESTMENT HIGHLIGHTS STRONG LOCATION The Carol Inn is located in Labrador City, on the mainland portion of the province of Newfoundland and Labrador. -

ENG-JAN14 Web.Pdf

COINS FROM THE ROYAL CANADIAN MINT 2014 | NUMBER 1 PRESERVED foreVER UNFORGETTABLE WITH WORLD- MOMENTS RENOWNED COINS. AT BOUTIQUES AND MINT.CA startING JanuarY 7 153rd BATTalION IN TraINIng. SOurCE: Canada. DEPT. OF NATIONAL DEFenCE / LIbrarY and ARCHIVES Canada / PA-022759 THE POWER OF A WAR-TIME EMBRACE. When Britain declared war on Germany on August 4, 1914, its entire Empire was drawn into the conflict, including Canada. Across the Dominion, men flocked to recruiting stations. Within two months, Canada’s pre-war militia that included a standing army of 3,110 men had grown to 33,000. Many were recent British immigrants or native-born Canadians of British origin, but among them were also more than 1,000 French Canadians, many First Nations as well as many others from diverse ethnic backgrounds. Five hundred soldiers from the British colonies of Newfoundland and Labrador also joined the ranks, while some 2,500 women stepped forward to serve as nurses. Train stations across Canada became the stage for tearful goodbyes and lingering embraces. The First World War was a true coming of age for the young nation, and the hope, fear, courage and deep sacrifice Canadians felt 100 years ago remain as poignant and inspiring today. Designed by Canadian artist Bonnie Ross, this coin depicts a couple’s emotional farewell as the first wave of volunteers boards for camp. Time stands still for this couple as they savour one last embrace before his departure. It is a poignant reminder of the sacrifices made by those who answered the call of duty, and their loved ones who remained on the home front. -

Hearing Aid Providers (Including Audiologists)

Hearing Aid Providers (including Audiologists) Beltone Audiology and Hearing Clinic Inc. 16 Pinsent Drive Grand Falls-Windsor, NL A2A 2R6 1-709-489-8500 (Grand Falls-Windsor) 1-866-489-8500 (Toll free) 1-709-489-8497 (Fax) [email protected] Audiologist: Jody Strickland Hearing Aid Practitioners: Joanne Hunter, Jodine Reid Satellite Locations: Baie Verte, Burgeo, Cow Head, Flower’s Cove, Harbour Breton, Port Saunders, Springdale, Stephenville, St. Albans, St. Anthony ________________________________ Beltone Audiology and Hearing Clinic Inc. 3 Herald Avenue Corner Brook, NL A2H 4B8 1-709-639-8501 (Corner Brook) 1-866-489-8500 (Toll free) 1-709-639-8502 (Fax) [email protected] Audiologist: Jody Strickland Hearing Aid Practitioner: Jason Gedge Satellite Locations: Baie Verte, Burgeo, Cow Head, Flower’s Cove, Harbour Breton, Port Saunders, Springdale, Stephenville, St. Albans, St. Anthony ________________________________ Beltone Hearing Service 3 Paton Street St. John’s, NL A1B 4S8 1-709-726-8083 (St. John’s) 1-800-563-8083 (Toll free) 1-709-726-8111 (Fax) [email protected] www.beltone.nl.ca Audiologists: Brittany Green Hearing Aid Practitioners: Mike Edwards, David King, Kim King, Joe Lynch, Lori Mercer Satellite Locations: Bay Roberts, Bonavista, Carbonear, Clarenville, Gander, Grand Bank, Happy Valley-Goose Bay, Labrador City, Lewisporte, Marystown, New-Wes- Valley, Twillingate ________________________________ Exploits Hearing Aid Centre 9 Pinsent Drive Grand Falls-Windsor, NL A2A 2S8 1-709-489-8900 (Grand Falls-Windsor) 1-800-563-8901 (Toll free) 1-709-489-9006 (Fax) [email protected] www.exploitshearing.ca Hearing Aid Practitioners: Dianne Earle, William Earle, Toby Penney ________________________________ Maico Hearing Service 84 Thorburn Road St. -

Student and Youth Services Agreement.Xlsx

2015-16 Student and Youth Services Agreement Approvals Organization Location Project Approved Amount BOTWOOD BOYS AND GIRLS CLUB Botwood Youth Cordinator$ 40,100 CBDC TRINITY CONCEPTION CORPORATION Carbonear Community Youth Coordinator$ 87,500 COLLEGE OF THE NORTH ATLANTIC St. John's Small Enterprise Co-Operative Placement Assistance$ 229,714 COLLEGE OF THE NORTH ATLANTIC St. John's Student Works and Service Program (SWASP)$ 90,155 COLLEGE OF THE NORTH ATLANTIC St. John's Partnership in Academic Career Education Employment Program $ 57,232 (PACEE) COMMUNITY YOUTH NETWORK CORNER BROOK & AREA Corner Brook Impact $ 5,071 CONSERVATION CORPS NEWFOUNDLAND AND St. John's Green Team$ 579,600 LABRADOR FOR THE LOVE OF LEARNING, INC St. John's Watering the Seeds$ 115,000 HARBOUR BRETON COMMUNITY YOUTH Harbour Breton Youth Entreprensurial Skills$ 35,000 HARBOUR BRETON COMMUNITY YOUTH Harbour Breton Youth Outreach Coordinator$ 52,500 HARBOUR GRACE COMMUNITY YOUTH Harbour Grace Changing Lanes$ 60,301 KANGIDLUASUK STUDENT PROGRAM INC Nain Student Program$ 7,000 MARINE INSTITUTE St. John's Youth Opportinities Coop Program$ 100,000 MARINE INSTITUTE St. John's Wage Subsidies for MESD$ 11,186 MEMORIAL UNIVERSITY OF NL St. John's Small Enterprise Co-Operative Placement Assistance$ 522,993 MEMORIAL UNIVERSITY OF NL St. John's Graduate Transition to Employment (GTEP)$ 200,000 MEMORIAL UNIVERSITY OF NL St. John's Student Works and Service Program (SWASP)$ 331,680 MEMORIAL UNIVERSITY OF NL St. John's Partnership in Academic Career Education Employment Program $ 67,732 (PACEE) NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR ASSOC OF Mount Pearl Youth Ventures$ 82,000 COMMUNITY BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT CORPORATIONS SKILLS CANADA-NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR St. -

BOARD MEETING –Norris Arm 1:00 P.M. December 7, 2017 Attendance

Central Newfoundland Waste Management P. O. Box 254, Norris Arm, NL, A0G 3M0 Phone: 709 653 2900 Fax :709 653 2920 Web: www.cnwmc.com E-mail: [email protected] BOARD MEETING –Norris Arm 1:00 p.m. December 7, 2017 Attendance Terry Best Badger/Buchans/Buchans Junction/Millertown – Ward 1 Kevin Butt NWI/Twillingate – Ward 3 Wayne Collins Fogo Island – Ward 4 Keith Howell Gander Bay – Ward 5 Lloyd Pickett Indian Bay – Ward 6 Glenn Arnold Terra Nova – Ward 7 Percy Farwell Town of Gander - Ward 8 Darrin Finn Town of Grand Falls-Windsor – Ward 9 Ross Rowsell Norris Arm/Norris Arm North – Ward 11 Derrick Luff Direct Haul – Ward 12 Ed Evans Chief Administrative Officer - CNWM Karen White Attwood Manager of Finance/Administration – CNWM Mark Attwood Manager of Operations – CNWM Jerry Collins Dept of Municipal Affairs and Environment - Conference Call Ian Duffett Dept of Municipal Affairs and Environment – Conference Call Apologies Brad Hefford Service NL Wayne Lynch Service NL Robert Elliott Point Leamington – Ward 2 Perry Pond Bishops Falls/Botwood/Lewisporte – Ward 10 1. Review of Minutes of November 9, 2017 MOTION: Moved by G. Arnold to adopt the minutes of November 9, 2017. Seconded by R. Rowsell. M/C 2. Business Arising Mayor Betty Clarke has stepped down as representative of Ward 10 (Botwood, Bishops Falls, and Lewisporte). Perry Pond will now represent Ward 10. 3. Technical Committee – Representatives from the Board, Government and engineers from the Towns of Grand Falls – Windsor and Gander will continue to sit at the Technical committee December 7, 2017 4. Financial Report MOTION: Moved by W.