Whole Language Works: Sixty Years of Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Integrating Literature Across the First Grade Curriculum Through Thematic Units

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 1992 Integrating literature across the first grade curriculum through thematic units Diana Gomez-Schardein Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Education Commons, and the Reading and Language Commons Recommended Citation Gomez-Schardein, Diana, "Integrating literature across the first grade curriculum through thematic units" (1992). Theses Digitization Project. 710. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/710 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. California State University San Bernardino INTEGRATING LITERATURE ACROSS THE FIRST GRADE CURRICULUM THROUGH THEMATIC UNITS A Project Submitted to The Faculty of the School ofEducation In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Master of Arts in Education: Reading Option By Diana Gomez-Schardein,M.A. San Bernardino, California 1992 APPROVED BY: Advisor : Dr. Adrla Klein eco/id#{eader : Mr. Jcfe Gray I I SUMMARY Illiteracy is one of the nation's eminent problems. Ongoing controversy exists among educators as to how to best combat this problem of growing proportion. The past practice has been to teach language and reading in a piecemeal,fragmented manner. Research indicates, however,curriculum presented as a meaningful whole is more apt to facilitate learning. The explosion of marvelous literature for children and adolescents provides teachers with the materials necessary for authentic reading programs. -

Reading the Past: Historical Antecedents to Contemporary Reading Methods and Materials

Reading Horizons: A Journal of Literacy and Language Arts Volume 49 Issue 1 October/November 2008 Article 4 10-2008 Reading the Past: Historical Antecedents to Contemporary Reading Methods and Materials Arlene Barry Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/reading_horizons Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Barry, A. (2008). Reading the Past: Historical Antecedents to Contemporary Reading Methods and Materials. Reading Horizons: A Journal of Literacy and Language Arts, 49 (1). Retrieved from https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/reading_horizons/vol49/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Education and Literacy Studies at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reading Horizons: A Journal of Literacy and Language Arts by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact wmu- [email protected]. Reading the Past • 31 Reading the Past: Historical Antecedents to Contemporary Reading Methods and Materials Arlene L. Barry, Ph.D. University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas Abstract This article addresses the International Reading Association’s foun- dational knowledge requirement that educators recognize histori- cal antecedents to contemporary reading methods and materials. The historical overview presented here highlights the ineffective methods and restrictive materials that have been discarded and the progress that has been made in the development of more effective and inclusive reading materials. In addition, tributes are paid to seldom-recognized innovators whose early efforts to improve read- ing instruction for their own students resulted in important change still evident in materials used today. Why should an educator be interested in the history of literacy? It has been frequently suggested that knowing history allows us to learn from the past. -

Literacy in India: the Gender and Age Dimension

OCTOBER 2019 ISSUE NO. 322 Literacy in India: The Gender and Age Dimension TANUSHREE CHANDRA ABSTRACT This brief examines the literacy landscape in India between 1987 and 2017, focusing on the gender gap in four age cohorts: children, youth, working-age adults, and the elderly. It finds that the gender gap in literacy has shrunk substantially for children and youth, but the gap for older adults and the elderly has seen little improvement. A state-level analysis of the gap reveals the same trend for most Indian states. The brief offers recommendations such as launching adult literacy programmes linked with skill development and vocational training, offering incentives such as employment and micro-credit, and leveraging technology such as mobile-learning to bolster adult education, especially for females. It underlines the importance of community participation for the success of these initiatives. Attribution: Tanushree Chandra, “Literacy in India: The Gender and Age Dimension”, ORF Issue Brief No. 322, October 2019, Observer Research Foundation. Observer Research Foundation (ORF) is a public policy think tank that aims to influence the formulation of policies for building a strong and prosperous India. ORF pursues these goals by providing informed analyses and in-depth research, and organising events that serve as platforms for stimulating and productive discussions. ISBN 978-93-89622-04-1 © 2019 Observer Research Foundation. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, copied, archived, retained or transmitted through print, speech or electronic media without prior written approval from ORF. Literacy in India: The Gender and Age Dimension INTRODUCTION “neither in terms of absolute levels of literacy nor distributive justice, i.e., reduction in gender Literacy is one of the most essential indicators and caste disparities, does per capita income of the quality of a country’s human capital. -

Literacy UN Acked: What DO WE MEAN by Literacy?

Memo 4 | Fall 2012 LEAD FOR LITERACY MEMO Providing guidance for leaders dedicated to children's literacy development, birth to age 9 L U: W D W M L? The Issue: To make decisions that have a positive What Competencies Does a Reader Need to impact on children’s literacy outcomes, leaders need a Make Sense of This Passage? keen understanding of literacy itself. But literacy is a complex concept and there are many key HIGH-SPEED TRAINS* service that moved at misunderstandings about what, exactly, literacy is. A type of high-speed a speed of one train was first hundred miles per Unpacking Literacy Competencies hour. Today, similar In this memo we focus specifically on two broad introduced in Japan about forty years ago. Japanese trains are categories of literacy competencies: skills‐based even faster, traveling The train was low to competencies and knowledge‐based competencies. at speeds of almost the ground, and its two hundred miles nose looked somewhat per hour. There are like the nose of a jet. Literacy many reasons that These trains provided high-speed trains are Reading, Wring, Listening & Speaking the first passenger popular. * Passage adapted from Good & Kaminski (2007) Skills Knowledge Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills, 6th ed. ‐ Concepts about print ‐ Concepts about the ‐ The ability to hear & world Map sounds onto letters (e.g., /s/ /p/ /ee/ /d/) work with spoken sounds ‐ The ability to and blend these to form a word (speed) ‐ Alphabet knowledge understand & express Based ‐ Word reading complex ideas ‐ Recognize -

Dyslexia and Structured Literacy Fact Sheet

Dyslexia and Structured Literacy Fact Sheet Written by Belinda Dekker Dyslexia Support Australia https://dekkerdyslexia.wordpress.com/ Structured Literacy • Structured literacy is a scientifically researched based approach to the teaching of reading. Structured literacy can be in the form of teachers trained in the use of structured literacy methodologies and programs that adhere to the fundamental and essential components of structured literacy. • Structure means that there is a step by step clearly defined systematic process to the teaching of reading. Including a set procedure for introducing, reviewing and practicing essential concepts. Concepts have a clearly defined sequence from simple to more complex. Each new concept builds upon previously introduced concepts. • Knowledge is cumulative and the program or teacher will use continuous assessment to guide a student’s progression to the next clearly defined step in the program. An important fundamental component is the automaticity of a concept before progression. • Skills are explicitly or directly taught to the student with clear explanations, examples and modelling of concepts. ‘The term “Structured Literacy” is not designed to replace Orton Gillingham, Multi-Sensory or other terms in common use. It is an umbrella term designed to describe all of the programs that teach reading in essentially the same way'. Hal Malchow. President, International Dyslexia Association A Position Statement on Approaches to Reading Instruction Supported by Learning Difficulties Australia "LDA supports approaches to reading instruction that adopt an explicit structured approach to the teaching of reading and are consistent with the scientific evidence as to how children learn to read and how best to teach them. -

Orton-Gillingham Or Multisensory Structured Language Approaches

JUST THE FACTS... Information provided by The International Dyslexia Association® ORTON-GILLINGHAM-BASED AND/OR MULTISENSORY STRUCTURED LANGUAGE APPROACHES The principles of instruction and content of a Syntax: Syntax is the set of principles that dictate the multisensory structured language program are essential sequence and function of words in a sentence in order for effective teaching methodologies. The International to convey meaning. This includes grammar, sentence Dyslexia Association (IDA) actively promotes effective variation, and the mechanics of language. teaching approaches and related clinical educational Semantics: Semantics is that aspect of language intervention strategies for dyslexics. concerned with meaning. The curriculum (from the beginning) must include instruction in the CONTENT: What Is Taught comprehension of written language. Phonology and Phonological Awareness: Phonology is the study of sounds and how they work within their environment. A phoneme is the smallest unit of sound PRINCIPLES OF INSTRUCTION: How It Is Taught in a given language that can be recognized as being Simultaneous, Multisensory (VAKT): Teaching is distinct from other sounds in the language. done using all learning pathways in the brain Phonological awareness is the understanding of the (visual/auditory, kinesthetic-tactile) simultaneously in internal linguistic structure of words. An important order to enhance memory and learning. aspect of phonological awareness is phonemic awareness or the ability to segment words into their Systematic and Cumulative: Multisensory language component sounds. instruction requires that the organization of material follows the logical order of the language. The Sound-Symbol Association: This is the knowledge of sequence must begin with the easiest and most basic the various sounds in the English language and their elements and progress methodically to more difficult correspondence to the letters and combinations of material. -

Whole Language Instruction Vs. Phonics Instruction: Effect on Reading Fluency and Spelling Accuracy of First Grade Students

Whole Language Instruction vs. Phonics Instruction: Effect on Reading Fluency and Spelling Accuracy of First Grade Students Krissy Maddox Jay Feng Presentation at Georgia Educational Research Association Annual Conference, October 18, 2013. Savannah, Georgia 1 Abstract The purpose of this study is to investigate the efficacy of whole language instruction versus phonics instruction for improving reading fluency and spelling accuracy. The participants were the first grade students in the researcher’s general education classroom of a non-Title I school. Stratified sampling was used to randomly divide twenty-two participants into two instructional groups. One group was instructed using whole language principles, where the children only read words in the context of a story, without any phonics instruction. The other group was instructed using explicit phonics instruction, without a story or any contextual influence. After four weeks of treatment, results indicate that there were no statistical differences between the two literacy approaches in the effect on students’ reading fluency or spelling accuracy; however, there were notable changes in the post test results that are worth further investigation. In reading fluency, both groups improved, but the phonics group made greater gains. In spelling accuracy, the phonics group showed slight growth, while the whole language scores decreased. Overall, the phonics group demonstrated greater growth in both reading fluency and spelling accuracy. It is recommended that a literacy approach should combine phonics and whole language into one curriculum, but place greater emphasis on phonics development. 2 Introduction Literacy is the fundamental cornerstone of a student’s academic success. Without the skill of reading, children will almost certainly have limited academic, economic, social, and even emotional success in school and in later life (Pikulski, 2002). -

Structured Literacy and the SIPPS® Program

Structured Literacy and the SIPPS® Program The International Dyslexia Association identifies Structured Literacy as an effective instructional approach for meeting the needs of students who struggle with learning to read. Structured Literacy utilizes systematic, explicit instruction to teach decoding skills including phonology, sound-symbol association, syllable types, morphology, syntax, and semantics. Structured Literacy instruction has been around for over a century and is sometimes referred to as systematic reading instruction, phonics-based reading instruction, the Orton-Gillingham Approach, or synthetic phonics, among other names. The SIPPS (Systematic Instruction in Phonological Awareness, Phonics, and Sight Words) program, developed by Dr. John Shefelbine, is a multilevel program that develops the word-recognition strategies and skills that enable students to become independent and confident readers and writers. Dr. Shefelbine’s research emphasizes systematic instruction, and in many ways parallels the Orton-Gillingham Approach. Structured Literacy The table below notes the elements of Structured Literacy aligned to the SIPPS program. Elements of Structured Literacy SIPPS Phonology Defined as the study of sound structure of spoken Phonological awareness activities appear in every words; includes rhyming, counting words in lesson in SIPPS Beginning, Extension, and Plus. spoken sentences, clapping syllables in spoken These activities begin with segmenting and words, and phonemic awareness (manipulation of blending, include rhyme, and increase in complexity sounds). to dropping and substituting phonemes. Sound-Symbol Association Defined as connecting sounds to print, including Spelling-sounds are explicitly taught throughout the blending and segmenting. This should occur two program. Sounds are taught in order of utility, which ways: visual to auditory (reading) and auditory to allows students to quickly begin to read connected visual (spelling). -

Research and the Reading Wars James S

CHAPTER 4 Research and the Reading Wars James S. Kim Controversy over the role of phonics in reading instruction has persisted for over 100 years, making the reading wars seem like an inevitable fact of American history. In the mid-nineteenth century, Horace Mann, the secre- tary of the Massachusetts Board of Education, railed against the teaching of the alphabetic code—the idea that letters represented sounds—as an imped- iment to reading for meaning. Mann excoriated the letters of the alphabet as “bloodless, ghostly apparitions,” and argued that children should first learn to read whole words) The 1886 publication of James Cattell’s pioneer- ing eye movement study showed that adults perceived words more rapidly 2 than letters, providing an ostensibly scientific basis for Mann’s assertions. In the twentieth century, state education officials like Mann have contin- ued to voice strong opinions about reading policy and practice, aiding the rapid implementation of whole language—inspired curriculum frameworks and texts during the late 1980s. And scientists like Cattell have shed light on theprocesses underlying skillful reading, contributing to a growing scientific 3 consensus that culminated in the 2000 National Reading Panel report. This chapter traces the history of the reading wars in both the political arena and the scientific community. The narrative is organized into three sections. The first offers the history of reading research in the 1950s, when the “conventional wisdom” in reading was established by acclaimed lead- ers in the field like William Gray, who encouraged teachers to instruct chil- dren how to read whole words while avoiding isolated phonics drills. -

Evidence Based Practice: Visual Motor Integration for Building Literacy: the Role of Occupational Therapy Francis, T., & Beck, C

Evidence Based Practice: Visual Motor Integration for Building Literacy: The Role of Occupational Therapy Francis, T., & Beck, C. (2018). Visual Motor Integration for Building Literacy: The Role of Occupational Therapy. OT Practice 23(15), 14–18. The Research: Occupational therapy interventions for visual processing skills were found to positively affect academic achievement and social participation. Key elements of intervention activities needed for progress include: fine motor activities, copying skills, gross motor activities, and a high level of cognitive interaction with completing activities. What is it? Visual information processing skills refers to “a group of visual cognitive skills used for extracting and organizing visual information from the environment and integrating this information with other sensory modalities and higher cognitive functions”. Visual information processing skills are divided into three components: visual spatial, visual analysis, and visual motor. Visual motor integration skills (i.e. eye-hand coordination) are related to an individual’s ability to combine visual information processing skills with fine motor or gross motor movement. Studies have found that visual motor integration is a component of reading skills in children in elementary school Specific Combination of Intervention Strategies Found to be Successful Fine motor activities ● Intervention activities: Manipulating small items (e.g., beads, coins); opening the thumb web space, separating the two sides of the hand; practicing finger isolation; -

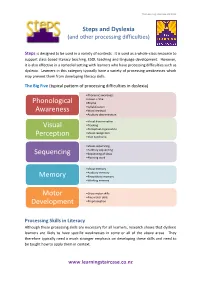

Phonological Awareness Visual Perception Sequencing Memory

The Learning Staircase Ltd 2012 Steps and Dyslexia (and other processing difficulties) Steps is designed to be used in a variety of contexts. It is used as a whole-class resource to support class-based literacy teaching, ESOL teaching and language development. However, it is also effective in a remedial setting with learners who have processing difficulties such as dyslexia. Learners in this category typically have a variety of processing weaknesses which may prevent them from developing literacy skills. The Big Five (typical pattern of processing difficulties in dyslexia) •Phonemic awareness •Onset + rime Phonological •Rhyme •Syllabification Awareness •Word retrieval •Auditory discrimination •Visual discrimination Visual •Tracking •Perceptual organisation •Visual recognition Perception •Irlen Syndrome •Visual sequencing •Auditory sequencing Sequencing •Sequencing of ideas •Planning work •Visual memory •Auditory memory Memory •Kinaesthetic memory •Working memory Motor •Gross motor skills •Fine motor skills Development •Proprioception Processing Skills in Literacy Although these processing skills are necessary for all learners, research shows that dyslexic learners are likely to have specific weaknesses in some or all of the above areas. They therefore typically need a much stronger emphasis on developing these skills and need to be taught how to apply them in context. www.learningstaircase.co.nz The Learning Staircase Ltd 2012 However, there are further aspects which are important, particularly for learners with literacy difficulties, such as dyslexia. These learners often need significantly more reinforcement. Research shows that a non-dyslexic learner needs typically between 4 – 10 exposures to a word to fix it in long-term memory. A dyslexic learner, on the other hand, can need 500 – 1300 exposures to the same word. -

TOWARD an UNDERSTANDING of WHOLE LANGUAGE Diane Stephens University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign January 1991

ILLINO I S UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. 370 .152 STX T2261 No. 524 COPY 2 C: C7 co n "TT Fl ui>r rnm r CD0~ Technical Report No. 524 0 p 6- TOWARD AN UNDERSTANDING COC OF WHOLE LANGUAGE co(0-mt Diane Stephens University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign January 1991 Center for the Study of Reading TECHNICAL REPORTS College of Education UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN 174 Children's Research Center 51 Gerty Drive Champaign, Illinois 61820 CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF READING Technical Report No. 524 TOWARD AN UNDERSTANDING OF WHOLE LANGUAGE Diane Stephens University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign January 1991 University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 51 Gerty Drive Champaign, Illinois 61820 The work upon which this publication was based was supported in part by the Office of Educational Research and Improvement under Cooperative Agreement No. G0087-C1001-90 with the Reading Research and Education Center. The publication does not necessarily reflect the views of the agency supporting the research. EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD 1990-91 James Armstrong Carole Janisch Gerald Arnold Bonnie M. Kerr Diana Beck Paul W. Kerr Yahaya Bello Daniel Matthews Diane Bottomley Kathy Meyer Reimer Clark A. Chinn Montserrat Mir Candace Clark Jane Montes John Consalvi Juan Moran Irene-Anna N. Diakidoy Anne Stallman Colleen P. Gilrane Bryan Thalhammer Barbara J. Hancin Marty Waggoner Richard Henne Ian Wilkinson Michael J. Jacobson Hwajin